INTRODUCTION

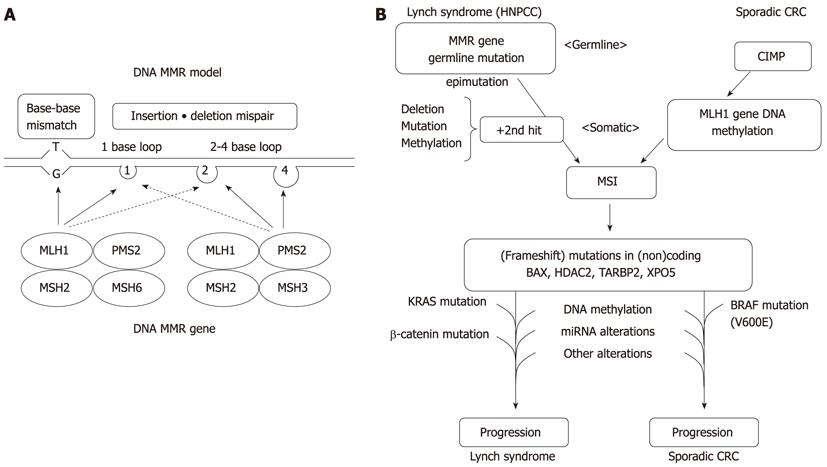

A type of genetic instability characterized by length alterations within simple repeated microsatellite sequences, termed microsatellite instability (MSI), occurs in a majority of patients with Lynch syndrome (also known as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer) by mutations and in a subset of sporadic gastrointestinal (GI) and other cancers by mainly epigenetic changes[1-10]. Genetic and epigenetic inactivation of DNA mismatch repair (MMR) genes results in the mutator phenotype, mutations in cancer-related genes, and cancer development (Figure 1). MSI underlies a distinctive carcinogenic pathway because MSI-positive (MSI+) cancers exhibit many differences in clinical, pathological, and molecular characteristics relative to MSI-negative (MSI-) cancers irrespective of their hereditary or sporadic origins. The differences in genotype can be explained because deficient MMR leads to a strong mutator phenotype with a very specific mutation spectrum. MSI accumulates frameshift mutations in repeated sequences located in coding regions of target tumor suppressor genes. The peculiar genotype of MSI+ cancers also includes specific patterns of gene regulation. MSI+ GI cancers often show an aberrant epigenetic pattern such as hypermethylation of various genes, including the key MMR gene, MLH1. The differences in genotype and phenotype between MSI+ and MSI- GI cancers are likely to be causally linked to their differences in biological and clinical features. Diagnostic characterization of the MSI status thus has implications in basic and clinical oncology. MiRNAs are small RNA molecules that regulate gene expression at the posttranscriptional level and are critical for many cellular functions[11-20]. There is accumulating evidence to support the notion that the interrelationship between MSI and miRNA plays a key role in the pathogenesis of GI cancer.

Figure 1 A model of DNA mismatch repair and molecular pathways for microsatellite instability+ colorectal cancers.

A: A model of the proposed mechanism of mismatch repair (MMR) proteins, illustrating patterns of relevant heterodimerization; B: The models for colorectal cancer (CRC) carcinogenesis are presented in parallel for Lynch syndrome and sporadic cases. HNPCC: Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer; MSI: Microsatellite instability; CIMP: CpG island methylator phenotype; MSI: Microsatellite instability.

MSI BY THE OVEREXPRESSION OF MIR-155 OR MIR-21

Various pathogenic events, including germline and somatic mutations, promoter methylation, and reduced histone acetylation[21], lead to inactivation of core MMR proteins. A vast majority of MSI+ cancers can be explained by mutation and/or epigenetic inactivation of the core MMR proteins[22]. The etiologies of the remaining MSI+ cancers remain poorly understood. In an unselected series of 1066 colorectal cancer (CRC) patients, 135 (13%) were MSI+[22]. Of these, 23 (6%) had germline mutations in one of the MMR gene, and 106 (79%) showed methylation of the MLH1 promoter. Approximately 5% of these MSI+ cancers displayed loss of expression of at least one of the core MMR proteins without a well-defined genetic or epigenetic cause[22].

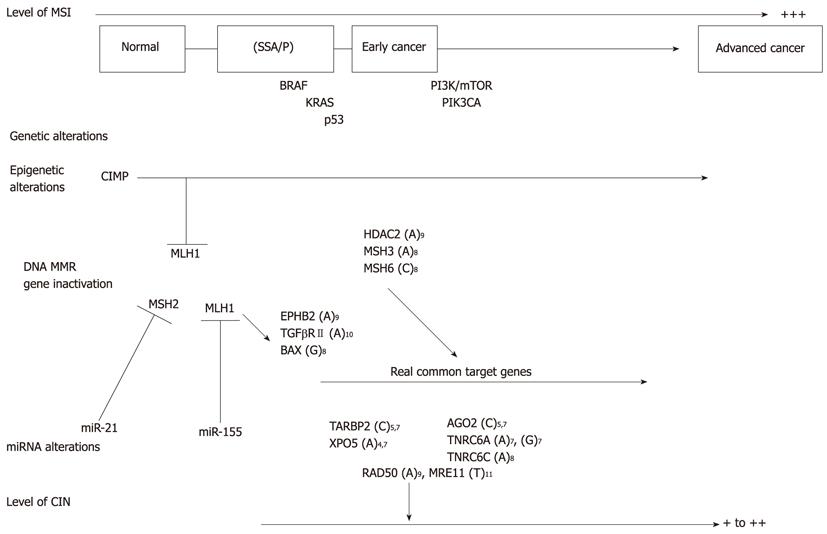

Vareli et al[23] have shown that overexpression of miR-155 significantly downregulates the core MMR proteins; namely, MLH1, MSH2, and, MSH6 in CRC cell lines, thus inducing an MSI. The downregulation of MLH1 and MSH2 proteins by miR-155 lead to destabilization of the respective heterodimeric complex proteins and a mutator phenotype[24]. An inverse correlation between miR-155 overexpression and the expression of MLH1 and MSH2 was further demonstrated in human CRC tissues. Most MSI+ cancers without a known cause of MMR inactivation show miR-155 overexpression. However, not all CRCs with increased miR-155 expression were MSI+. It is also possible that miR-155 affects other related DNA repair proteins, thus enhancing the phenotypic effect of MMR defects. Although further confirmation is required, the results suggest that miR-155 overexpression is an additional mechanism underlying the development of MSI in cancer (Figure 2)[23].

Figure 2 Cancer progression of sporadic microsatellite instability+ colorectal cancers.

The model for microsatellite instability (MSI)+ colorectal cancer progression is presented based on levels of MSI and chromosomal instability (CIN), and genetic, epigenetic and miRNA alterations. SSA/P: Sessile serrated adenomas/polyps; CIMP: CpG island methylator phenotype; MMR: Mismatch repair.

The reduced expression of a single allele of the adenomatous polyposis coli and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β receptor I gene has been linked to CRC[25,26]. Thus, incomplete repression of MMR proteins by miR-155 is not unique to tumor suppressor genes in cancer. Recently, miRNAs have been suggested to act as transactivating elements involved in allele and gene expression regulation[27,28]. These results support the notion that miRNAs play a role in the non-Mendelian regulation of MMR genes.

miR-21 is overexpressed in various types of human cancers, including CRC[29]. Valeri et al[30] reported that miR-21 directly targets the 3’ untranslated region (UTR) of MSH2 and MSH6 mRNA, resulting in downregulation of protein expression. The inverse correlation between miR-21 overexpression and MSH2 expression was shown in CRC tissues. Cells that overexpress miR-21 showed significantly reduced 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)-induced G2/M damage arrest and apoptosis that is characteristic of defective MMR. Because miR-21 expression could increase in cell lines continuously exposed to 5-FU[31], cancer cells may develop a secondary resistance to 5-FU through miR-21 overexpression. Thus, miR-21-dependent downregulation of MSH2-MSH6 may be responsible for both primary and secondary resistance to 5-FU.

TARGET CANCER-RELATED GENES OF MSI

The instability in cancer-related genes at coding microsatellites causes frameshift mutations and functional inactivation of affected proteins, thereby providing a selective growth advantage to deficient MMR cells[32]. For instance, TGF-βreceptor II and the pro-apoptotic gene BAX are frequently inactivated by slippage-induced frameshift mutations in mononucleotide tracts present in their gene coding regions[33,34]. These findings have provided proof for the causative link between MSI and mutations in cancer-related genes, and they were also convincing examples of the differences between the mutator and suppressor pathways for cancer. These genes have also been mutated in cancers in the suppressor pathway, but at decreased frequencies and not by slippage-linked frameshifts[35,36].

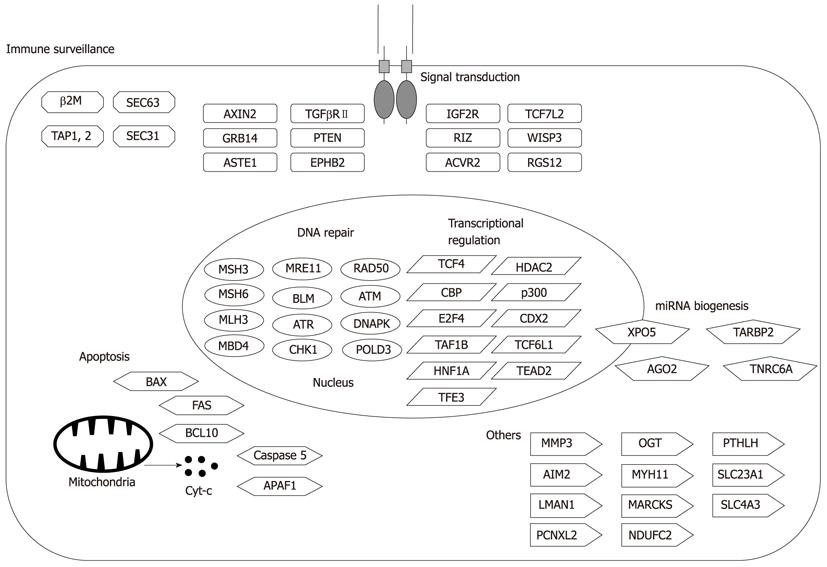

A number of cancer-related genes mutated in MSI+ cancers have been reported (Figure 3). Mutations that promote cancer cell growth are assumed to be the driving force during MSI+ carcinogenesis and are designated as real common target genes (Figure 2)[37]. Mutations of microsatellite-harboring genes that do not contribute to carcinogenesis are designated as bystander genes. However, it is not always clear which mutations are “driver mutations” and which are “passenger mutations”[9,38]. The Selective Targets database (SelTarbase) (http://www.seltarbase.org) of human mononucleotide-microsatellite mutations and their potential impact to carcinogenesis and immunology has been developed[39]. The database includes a comprehensive database of all human coding, untranslated, non-coding RNA and intronic mononucleotide repeat tracts and is useful for basic and clinical oncology.

Figure 3 Representative target genes in microsatellite instability+ gastrointestinal cancers.

A number of cancer-related genes mutated in microsatellite instability+ gastrointestinal cancers have been reported. The relevance of each mutation is not necessarily proven.

Because MSI+ cancers accumulate many mutations, disruption of cell growth and survival regulation can be accomplished in different cancers by mutations in different genes of the same signaling pathways[40]. Therefore, genes with infrequent and/or monoallelic mutations should not be regarded as irrelevant. Thus, the relevance of microsatellite-specific mutations in MSI+ cancers can be proven only when there is supporting evidence for functionality irrespective of mutation incidence[2].

Target cancer-related genes of MSI+ cancers can be functionally categorized as tumor suppressors and genes involved in DNA repair, cell cycle, cell proliferation, apoptosis and others (Figure 3). Interestingly, every human MMR gene except MLH1 contains a mononucleotide repeat of at least A7[41]. Thus, frameshift mutations of MSH3 and MSH6 led to the concept of “the mutator that mutates the other mutator” (Figure 2)[42].

The spectrum of mutations of target genes could affect cancer biology, therapeutic response, and prognosis of patients. Most putative MSI target genes have been proposed mainly on the basis of high mutation frequency detected within their coding regions. However, genes containing microsatellites that are located within noncoding regulatory regions, such as introns, promoters, and 5′ and 3′ UTRs, could be also mutated in MSI+ cancers. Alterations within untranslated mononucleotide repeat tracts can alter transcription level or transcript stability. It has been suggested that some intronic repeat mutations in genes, such as ATM, MYB[43], and MRE11[44], play a role in MSI carcinogenesis[45]. Decreased matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-3 expression due to insertions and/or deletions in the MMP-3 promoter region led to a decrease in the levels of the active MMP-9 form, which may explain the less invasive potential of MSI+ cancer cells[46] and the propensity for a good prognosis in the case of MSI+ CRCs[47].

Genomic copy number changes are frequently observed in cancers. It is well known that MSI+ cancers show less genomic copy number changes and are mostly diploid[48]. However, genes responsible for chromosomal instability (CIN) could be mutated in MSI+ cancers, and these defects may be selected during the course of cancer progression (Figures 2 and 3)[49]. Furthermore, mutations of RAD50 and MRE11 are reportedly associated with defects in nonhomologous end-joining, leading to chromosomal alterations during cancer progression[45].

Altered histone modifications that affect chromatin structures are also involved in carcinogenesis[49]. Epigenetic modifier genes could also be MSI target genes. Ropero et al[50] detected frameshift mutations in the histone deacetylase (HDAC) 2 gene in MSI+ GI cancers. This HDAC2 mutation made mutation-positive cancer cells more resistant to the antiproliferative and proapoptotic effects of certain HDAC inhibitors such as trichostatin A, but not to others such as butyric acid and valproic acid. Since HDAC inhibitors may serve as therapeutic agents for cancer, these findings support the use of HDAC2 mutation status in future pharmacogenetic treatment[50].

MIRNA PROCESSING MACHINERY GENES AS MSI TARGET GENES

MiRNAs are small noncoding RNAs that regulate gene expression at the posttranscriptional level and are critical in many biological processes and cellular pathways (Figure 4)[11-20]. MiRNA expression profiles of human cancers have been characterized by an overall mature miRNA downregulation[51-53]. The causes of the aberrant miRNA expression patterns in cancer involve DNA copy number amplification or deletion[54], inappropriate transactivation, transcriptional repression by oncogenic and/or other factors[55], failure of miRNA post-transcriptional regulation[56], and genetic mutation[57] or transcriptional silencing associated with hypermethylation of CpG island promoters[58-62].

Figure 4 MiRNA biogenesis and genes mutated in microsatellite instability+ gastrointestinal cancers.

A consequence of perfect complementarity between miRNA and mRNA is mRNA cleavage and degradation. Imperfect alignment represses gene translation. ORF: Open reading frame; RISC: RNA-induced silencing complexes.

The control of the miRNA biosynthesis pathway is important in the spatiotemporal pattern of miRNA expression in cells. Thus, impaired miRNA processing pathways may themselves be targets of genetic and/or epigenetic disruption in cancer[63,64]. Recently, it has been reported that mitogenic signaling can be translated into changes in cell viability and proliferation through the miRNA biogenesis pathway. A TAR RNA-binding protein 2 (TARBP2) gene encodes TRBP, an essential functional partner of DICER1 (Figure 4)[65,66]. TARBP2 is phosphorylated under normal growth conditions, which increases the stability of TARBP2 and DICER[67]. Upon growth factor stimulation, MAPK/ERK pathway increases TARBP2 phosphorylation, leading to a coordinated increase in levels of growth-promoting miRNA and a decrease in the expression of let-7 tumor suppressor miRNA. In contrast, pharmacological inhibition of MAPK/ERK resulted in an anti-growth miRNA profile[67]. These results further suggest the important role of miRNA processing mediated by TARBP2 in preservation of a normal, untransformed cell state[17].

Melo et al[68] have found truncating heterozygous mutations in TARBP2 in MSI+ cancer cell lines and in primary sporadic and hereditary MSI+ GI cancers (Figure 4). TARBP2 mutations diminished TRBP protein expression, resulting in impaired miRNA processing and enhanced cellular transformation. The TRBP impairment was associated with a secondary defect in DICER1 activity by destabilization of the DICER1 protein. Thus, TARBP2 mutations may explain overall miRNA downregulation in a subset of MSI+ cancers. Because the restoration of efficient miRNA production by the reintroduction of TRBP can suppress cancer cell growth, these findings are important for the development of new therapeutic strategies for the treatment of cancer[68].

MUTATIONS OF THE EXPORTIN 5 GENE

Because of the nuclear retention of certain precursor miRNAs (pre-miRNAs), mature miRNA expression levels are not consistent with pre-miRNA expression levels in various human cancer cell lines[17]. Thus, defects in the nuclear export of pre-miRNAs may be one of the mechanisms underlying the global impairment of mature miRNAs in human cancer. The exportin 5 (XPO5) mediates nuclear export of pre-miRNA (Figure 4). Melo et al[69,70] have identified inactivating heterozygous mutations of XPO5 in MSI+ cancer cell lines and in primary sporadic and hereditary MSI+ GI cancers. The mutant form of XPO5 does not comprise a C-terminal region that is important for the formation of the pre-miRNA/XPO5/Ran-GTP ternary complex. Thus, the XPO5 defect trapped certain pre-miRNAs in the nucleus, reduced miRNA processing, and impaired miRNA-target inhibition. It is important to note that the restoration of XPO5 functions rescued the disturbed export of critical tumor-suppressive pre-miRNAs, which results in tumor suppression[69].

Interestingly, although the heterozygous XPO5 mutation decreased accumulation of a fraction of detectable miRNAs, many others were not affected. It seems that XPO5 does not bind to pre-miRNAs universally but has certain substrate preferences, which are possibly mediated by sequence or structure[38]. Strategies directed toward stimulating the activity of miRNA processing factors and restoring the production of mature growth inhibitory miRNAs may have therapeutic value[69].

MUTATED MIRNA MACHINERY PHENOTYPE AS A NEW CANCER PHENOTYPE

Recent works have suggested that the other component of the miRNA biogenesis pathway, DICER1, is a haploinsufficient tumor suppressor[71,72]. Therefore, it appears that at least three components of the miRNA biogenesis pathway are haploinsufficient tumor suppressors, with TARBP2 and XPO5, but not DICER, mutations prevalent in MSI+ cancers[38]. In addition, the miRISC components AGO2, TNRC6A, and TNRC6C can also be mutated in MSI+ cancers (Figure 4)[73], although the functional significances remain to be determined[38,70].

From these observations, a new cancer phenotype known as mutated miRNA machinery phenotype (MMMP) has been proposed for MSI+ CRCs having mutations in the miRNA machinery genes and the deregulated miRNAome. Although larger studies are required to fully characterize and validate this feature as a criterion for classification, a broader miRNAome-modifying approach may be effective for cancer patients with MMMP[15].

TRANSCRIPTOMIC DIFFERENCES BETWEEN MSI+ AND MSI- CRCS

As molecular markers, gene expression profiles are being developed for many cancers. Array technology has identified a number of genes that are expressed differentially between MSI+ and MSI- CRCs[74-76]. By using supervised analysis of cDNA microarray data, Giacomini et al[77] identified a robust expression signature distinguishing MSI+ and MSI- CRC cell lines. By using high-density oligonucleotide microarrays, Kruhoffer et al[78] constructed a gene signature that distinguished MSI+ and MSI- CRCs. The authors further constructed a signature that distinguished sporadic and hereditary cases of MSI+ CRCs. Identification of a signature for MMR deficiency would be relevant, both biologically and clinically[78].

As for miRNAs, Lanza et al[79] analyzed 16 MSI+ and 23 MSI- CRCs for genome-wide expression of miRNA and mRNA. On the basis of combined miRNA and mRNA expression, a molecular signature comprising 27 differentially expressed genes, including 8 miRNAs, could correctly distinguish MSI+ and MSI- CRCs. Among the differentially expressed miRNAs, various members of the oncogenic miR-17-92 family were significantly upregulated in MSI- cancers. Among these, miR-17-5p, miR-20, miR-25, miR-92-1, miR-92-2, miR-93-1, and miR-106a were significantly upregulated in MSI- when compared with MSI+ CRCs. Because members of the miR-17-92 family act as oncogenes, these results may explain, at least in part, the less aggressive behavior of MSI+ CRCs when compared with their MSI- counterparts.

Earle et al[80] analyzed 22 MSI-H, including 6 Lynch syndrome, 8 MSI-L, and 25 MSS CRCs for a selected panel of 24 miRNAs. Relative expression of miR-26b, miR-31, miR-92, miR-155, miR-196a, and miR-223 were significantly different among MSI subgroups, and miR-31 and miR-223 were overexpressed in CRCs of patients with Lynch syndrome. These findings indicate that miRNA expression in CRC is associated with MSI status, including Lynch syndrome and MSI-L, and that miRNAs may play significant roles in these MSI subgroups in addition to having possible effects on cancer characteristics.

Slattery et al[81] analyzed 70 CRCs for 866 miRNAs using microarrays. At the 1.5-fold level, 143 miRNAs were differentially expressed in MSI+ CRCs. MiR-139-3p, miR-223, and miR-370 were upregulated and miR-24-2, miR-424, miR-552, and let-7g were downregulated at a level of 1.5-fold or greater in MSI+ CRCs when compared with MSI- CRCs.

Thus, differentially expressed miRNAs are likely to be relevant, both biologically and clinically, although their functional significances remain to be determined. High levels of miR-21 in the stroma of CRCs reportedly predict short disease-free survival in stage II CRC patients; however, the levels are not associated with the MSI status[82].

DEFECTIVE MMR AS A NOVEL THERAPEUTIC TARGET

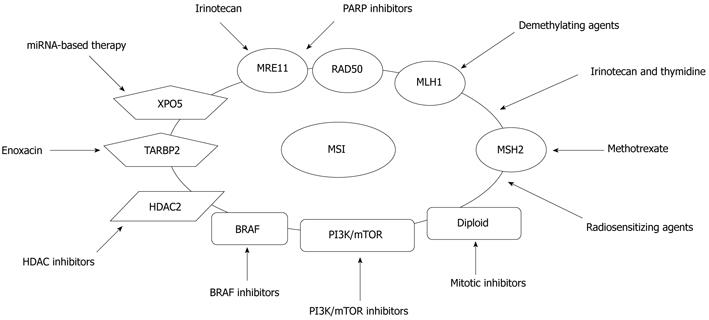

MSI+ cancers may be managed more effectively with novel targeted therapies based on molecular alterations (Figure 5). A combination of treatments that target both primary alterations of DNA MMR gene and secondary alterations, such as frameshift mutations of target genes, may be also effective. A synthetic lethal relationship, where the simultaneous inhibition of two different regulatory pathways leads to cell death, is a recent therapeutic strategy[83]. Therefore, identification of synthetic lethal interactions with MMR deficiency could potentially lead to the identification of specific therapeutic targets[84]. The inhibition of poly (adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase (PARP) is a potential synthetic lethal therapeutic strategy for the treatment of cancers with specific DNA repair defects, such as a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation[85].

Figure 5 Targeted therapies based on molecular alterations in microsatellite instability+ colorectal cancers.

Microsatellite instability+ cancers may be managed more effectively with novel targeted therapies based on molecular alterations. MSI: Microsatellite instability; HDAC: Histone deacetylase; PI3K/mTOR: Phosphoinositide 3-kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin; XPO5: Exportin 5.

A subset of MSI+ CRCs may also be suitable for this strategy. A novel PARP inhibitor, ABT-888, showed preferential activity on MSI+ CRC cell lines harboring mutations in both MRE11 and RAD50 genes when compared with MSI- cell lines that were wild type for both genes[86]. Recently, Vilar et al[87] reported that MSI+ CRCs deficient in double strand break (DSB) repair due to MRE11 mutations show a higher sensitivity to PARP-1 inhibition. A phase II study assessing the efficacy of a PARP-1 inhibitor, olaparib, in CRCs stratified by MSI status is ongoing. Further clinical studies regarding combinations of a PARP-1 inhibitor with other DSB-inducing therapies, such as radiation or irinotecan, are warranted in MSI+ CRCs with MRE11 mutations. Although these results need to be confirmed in other settings, they suggest that specific mutations such as MRE11 can be used to exploit the concept of synthetic lethality in MSI+ cancers, which has been successful in BRCA1-mutant breast cancers[88].

Methotrexate reportedly induces oxidative DNA damage and is selectively lethal to cancer cells with MSH2 defects[84,89]. Thus, a synthetic lethal relationship between deficient MSH2 and treatment with methotrexate led to a phase II trial, incorporating measurement of 8-oxoG DNA lesions as a biomarker, in metastatic CRC patients with germline mutation or loss of MSH2.

Because MSI+ CRCs often harbor a near diploid stable karyotype, these cancers may be sensitive to mitotic inhibitors, such as taxanes and kinesin-5 inhibitors[90]. To determine the effect of CIN and MSI on the efficacy of the microtubule-stabilizing agent patupilone/EPO960, a phase II study called CIN and Anti-Tubulin Response Assessment in CRC is ongoing. It is assumed that MSI+ CRC patients will benefit more than MSI- CRC patients.

Gene expression signatures can also be used for new MSI+ cancer therapies. Fourteen of the 164 compounds were shown to target MSI+ cancer cell lines using combined gene expression data sets and a connectivity map[91]. Rapamycin, LY-294002, 17-(allylamino)-17-demethoxygeldanamycin, and trichostatin A were the most convincing candidate compounds. MSI+ cell lines with MLH1 hypermethylation were preferentially targeted by rapamycin and LY-294002 when compared with MSI- cells. These results underscore the relevant role of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and its therapeutic application in MSI+ cancer, although its clinical significance needs confirmation.

MiRNA-based cancer therapy is limited mainly to targeting a single miRNA[92,93]. However, if most cancers are characterized by a defect in miRNA production and global mature miRNA downregulation[51-53], restoration of the global miRNAome may be an attractive approach in cancer therapy. Melo et al[94] have found that the small molecule enoxacin, a fluoroquinolone used as an antibacterial compound, enhances the miRNA-processing machinery by binding to TRBP. Enoxacin was shown to inhibit the growth of a variety of cancer cells. The enhanced miRNA-processing activity by enoxacin did not depend on general fluoroquinolone activity but on the unique chemical structure of enoxacin. These results highlight the key role of disturbed miRNA expression in carcinogenesis, and suggest the potential of novel miRNA-based cancer therapy to restore the disrupted miRNAome of cancer cells.

Finally, it remains to be determined whether XPO5 mutations can be exploited therapeutically. Since it is difficult to directly restore XPO5 activity, restoring miRNA accumulation by alternative methods may be a more realistic strategy. Given that only a few deregulated tumor suppressor miRNAs appear to be critical for the tumor-promoting effect of XPO5 mutations, it may be possible to supply those miRNAs exogenously as miRNA duplexes that would not need to undergo nuclear export. It may also be possible to find a subset of important target genes of deregulated tumor suppressor miRNAs, which may be responsive to inactivation by conventional pharmacological methodologies or novel biologics.

CONCLUSION

The biological and clinical implications of MSI in GI cancers continue to develop. Recent findings, such as overexpression of miR-21 and miR-155 and mutations of TARBP2 and XPO5 in MSI+ GI cancers, further suggest the important interrelationship between MSI and miRNA in MSI carcinogenesis. The clinicopathological, genetic, epigenetic, prognostic, and therapeutic characteristics of MSI+ cancers are becoming clear, but remain to be fully determined. Analysis of MSI status in cancer patients is warranted as a screening for Lynch syndrome; it could be a potential predictive marker of response to chemotherapy. Since molecular targeting therapeutics are being used in clinical settings and trials, it seems important to clarify if molecular target genes are differentially regulated between MSI+ and MSI- cancers and if the MSI status has the prognostic or predictive significance in metastatic CRC. Further analysis is required to gain insight into MSI carcinogenesis, for a better understanding of disease pathogenesis, and for the development of new diagnostic and/or therapeutic approaches targeting essential pathogenetic alterations.

Peer reviewers: Dr. John Souglakos, Department of Medical Oncology, University Hospital of Heraklion and Laboratory of Cancer Biology, 71110 Heraklion, Greece; Dr. Jose Perea, Department of Surgery, 12 De Octubre University Hospital, Rosas De Aravaca 82A, 28023 Madrid, Spain

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN