INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has become a major cause of liver disease with approximately 170 million people infected worldwide[1]. The severity of the disease varies widely, ranging from asymptomatic carrier state to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. HCV chronic infection is often associated with abnormal immunological responses that can result in several extrahepatic conditions such as membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, Sjögren’s syndrome, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, lichen planus, porphyria cutanea tarda, and mixed cryoglobulinemia[2]. Even though these conditions occur relatively infrequently, they significantly increase morbidity and mortality among HCV patients. Although sensory or motor peripheral neuropathy may be observed in a significant proportion of HCV-infected patients, central nervous system (CNS) involvement is uncommon, especially in cryoglobulin-negative subjects[3]. Here, we describe a patient with peripheral neuropathy combined with CNS vasculitis as primary manifestations of chronic HCV infection.

CASE REPORT

A previously healthy 37-year-old Caucasian woman presented to the emergency department in May 2003, with a 9-mo history of malaise, loss of appetite, and substantial weight loss (19.96 kg). Over the previous month, she had developed fatigue and muscle weakness, and become unable to perform several activities of daily living, such as hair brushing, climbing stairs and doing household chores. There was no history of blood transfusions or intravenous drug abuse. The patient was conscious and oriented to time and place. On examination, atrophy of the dorsal interosseous muscles, flaccid quadriparesis with hyporeflexia, and symmetrical distal sensory loss were noted. An electroneuromyographic study revealed sensorimotor polyneuropathy.

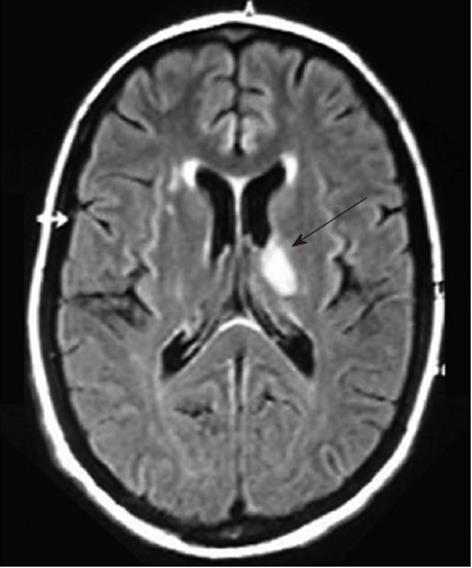

Over the next 24 h, she became increasingly disoriented. Magnetic resonance imaging of the head showed a T1 low, T2 and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) high-signal lesion in the left thalamus, approximately 1.5 cm in diameter (Figure 1), which probably represented ischemic injury. In addition, small foci of increased signal intensity at the semioval center and subcortical white matter were identified on T2 and FLAIR sequences. A rheumatologic panel including antinuclear antibody, rheumatoid factor, anti-DNA and cardiolipin antibodies was negative. Thyroid-stimulating hormone, vitamin B12, and aminotransferases levels were within normal limits. Further testing showed negative serology for hepatitis B virus, HIV, syphilis, cytomegalovirus, and human T-lymphotropic virus 1/2. Enzyme immunoassay to detect HCV antibody was positive, as well as serum HCV-RNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). A liver biopsy confirmed chronic hepatitis with mild necroinflammatory activity and no fibrosis. We then considered that the diagnosis of CNS vasculitis and peripheral polyneuropathy was probably related to chronic HCV infection. Serum cryoglobulins were persistently negative after seven determinations. The patient was initially treated with intravenous methylprednisolone followed by oral prednisone, with resolution of her symptoms. Subsequently, standard interferon-α (3 mU three times per week) plus ribavirin (1 g/d) were added to steroid maintenance therapy. During HCV treatment, an attempt to reduce prednisone dose resulted in the development of necrotic lesions on the right forefoot (Figure 2), which led to its amputation. In spite of permanent discontinuation of antiviral drugs and the need for increasing corticosteroid dosage, the patient showed sustained virological response, with HCV RNA persistently undetectable in serum by sensitive PCR-based assay. She remains asymptomatic, until last seen, under low dose prednisone.

Figure 1 Magnetic resonance imaging of the head showing a 1.

5-cm, high-signal lesion in the left thalamus, suggestive of ischemic injury (arrow).

Figure 2 Necrotic lesions on the right forefoot due to severe vasculitis.

DISCUSSION

Although the precise frequency of peripheral neuropathy in HCV-infected patients is unknown, it is considered the most common neurological complication in this setting. In a French cohort of 321 subjects with chronic hepatitis C, symptomatic peripheral neuropathy was observed in 9% of the cases[4]. Even though the neurological findings were more frequent among cryoglobulin-positive patients, in this study, a significant proportion of cryoglobulin-negative individuals presented with peripheral nervous system involvement (17% vs 8%). Other reports of peripheral neuropathy in HCV-infected patients without detectable cryoglobulins[5-7] indicate that, although the presence of cryoglobulins seems to be an important feature in these cases, there are possibly other factors contributing to the development of peripheral neuropathy. In a study including 51 patients with HCV infection and neuropathy, Nemni et al[7] showed that 22% of the subjects had undetectable serum cryoglobulins. Cryoglobulin-negative individuals were more likely to have mono- or multiple neuropathy. Interestingly, the morphological findings in the sural nerve from cryoglobulin-negative and -positive patients are consistent with an ischemic mechanism of nerve damage. The authors stated that the vasculitic process in cryoglobulin-negative HCV subjects was probably secondary to complement pathway activation by HCV itself, or by an interaction between the virus and the host immune system. A direct role of HCV in the pathogenesis of peripheral neuropathy was also proposed, based on the finding of HCV RNA in nerve biopsy specimens[8]; however, this association remains to be confirmed.

Specific CNS involvement is more rarely reported in HCV-infected patients. CNS involvement, however, may present different facets, such as fatigue, depression, cognitive impairment and vasculitis. Although it may be the initial extrahepatic manifestation of HCV infection, well-documented reports on CNS involvement in patients with HCV-associated vasculitis are rare and include mostly cryoglobulin-positive patients[9-11]. Stroke episodes, transient ischemic attacks, progressive reversible ischemic neurological deficits, lacunar infarctions, or encephalopathic syndrome, commonly attributed to ischemia or rarely to hemorrhage, may occur[12]. Similar to HCV-related peripheral neuropathy, the mechanism behind the CNS vasculitic process in HCV infection is poorly understood, but it has been postulated that recurrent cryoglobulin precipitation with complement fixation and/or HCV-related induction of the innate mechanism of complement activation might be involved in ischemic and inflammatory tissue damage[7]. Although the exact pathway is not known, HCV-induced vasculitis without cryoglobulinemia by the other mechanisms previously discussed for peripheral neuropathy may be responsible for the CNS findings in this case.

The treatment of HCV-associated peripheral neuropathy in cryoglobulin-positive individuals is based on anti-HCV drugs. Combination therapy with interferon (pegylated or not) plus ribavirin may induce a complete clinical response in a significant proportion of patients with HCV-related systemic vasculitis, and consequently, in those with cryoglobulin-related peripheral neuropathy[13,14]. The role of HCV therapy in subjects with cryoglobulin-negative peripheral neuropathy is unclear. Lidove et al[5] have reported significant neurological improvement in two cryoglobulin-negative patients treated with interferon monotherapy. However, long-term follow-up was not reported and the possibility of development or worsening of peripheral neuropathy in interferon-based treatments is a major concern in this setting[15]. Data about the safety and efficacy of interferon-based regimens in the treatment of HCV-associated CNS vasculitis are even scarcer. There are a few case reports showing favorable outcomes in cryoglobulinemic subjects treated with corticosteroids or interferon for CNS involvement[12,16,17]. However, such reports cannot support a solid recommendation, especially for those patients with cryoglobulin-negative CNS vasculitis. In addition, it should be emphasized that for cases of severe cryoglobulinemia-associated vasculitis (as those with rapidly progressive renal failure or neurological involvement), it is recommended that antiviral therapy should be delayed for 2-4 mo, while they are submitted to aggressive therapy with plasmapheresis, corticosteroids (intravenous methylprednisolone followed by oral prednisone), and either cyclophosphamide or rituximab[18].

In this report, we describe a patient with peripheral neuropathy combined with an ischemic CNS event as primary manifestations of chronic HCV infection. The absence of other classical risk factors for ischemic stroke, the association with peripheral vasculitis and the improvement observed after steroid therapy suggests a vasculitic origin for the neurological findings. Although this report cannot prove a definite cause-and-effect of HCV infection and the neurological manifestations observed, an important role of HCV is suggested by the significant improvement observed after the HCV sustained virological response. Another interesting finding in the present case was the achievement of sustained viral clearance in spite of the prolonged use of steroids. Although we have not been able to evaluate viral load during therapy sequentially, previous studies have shown that exposure to steroids increases HCV viral load, both in liver transplant patients and in the non-transplant setting[19,20].

In conclusion, our case highlights the need for clinicians to broaden consideration of differential diagnoses, with particular attention to atypical features of common diseases. Testing for HCV should be performed in all cases of neurological signs of uncertain origin, even in the absence of usual risk factors for hepatitis C. Successful antiviral therapy may lead to a significant improvement of neurological manifestations and should be considered in these cases.