Published online May 7, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i17.2061

Revised: February 6, 2012

Accepted: February 16, 2012

Published online: May 7, 2012

AIM: To investigate perioperative patient morbidity/mortality and outcome after cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC).

METHODS: Of 150 patients 100 were treated with cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC and retrospectively analyzed. Clinical and postoperative follow-up data were evaluated. Body mass index (BMI), age and peritoneal carcinomatosis index (PCI) were chosen as selection criteria with regard to tumor-free survival and perioperative morbidity for this multimodal therapy.

RESULTS: CRS with HIPEC was successfully performed in 100 out of 150 patients. Fifty patients were excluded because of intraoperative contraindication. Median PCI was 17 (1-39). In 89% a radical resection (CC0/CC1) was achieved. One patient died postoperatively due to multiorgan failure. Neither PCI, age nor BMI was a risk factor for postoperative complications/outcome according to the DINDO classification. In 9% Re-CRS with HIPEC was performed during the follow-up period.

CONCLUSION: Patient selection remains the most important issue. Neither PCI, age nor BMI alone should be an exclusion criterion for this multimodal therapy.

- Citation: Königsrainer I, Zieker D, Glatzle J, Lauk O, Klimek J, Symons S, Brücher B, Beckert S, Königsrainer A. Experience after 100 patients treated with cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(17): 2061-2066

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i17/2061.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i17.2061

Peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC) is generally considered to be a terminal disease and for a long time was viewed as incurable. Based on the rationale of a disease limited to the abdominal compartment[1-8], the pioneering work of Sugarbaker made it possible for certain tumor entities with PC to have the option to be cured by radical cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC). Patient prognosis is determined by the feasibility of complete cytoreduction (CC) and therefore a compulsory patient selection remains the Achilles heel[9]. Since the surgical procedure itself is challenging, postoperative morbidity and mortality must be considered in the preoperative evaluation process in addition to the extent of tumor spread. A high tumor load, causing a high peritoneal carcinomatosis index (PCI), is associated with poor prognosis with regard to disease-free and overall survival[10]. Age is commonly widely accepted as a selection criteria per se for major tumor resections. Most groups restrict cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC to patients aged under 65 years. Similarly, a high body mass index (BMI) often hampers major surgery and obese patients have more complications in general. A valid surgical complication score was developed by Dindo et al[11]. He defines 5 grades of complications, whereas grade 1 is any deviation from normal postoperative course; grade 2 requiring pharmacological treatment; grade 3 any radiological, endoscopic or surgical intervention; grade 4 a life threatening complication and grade 5 death.

We here report our experience with 100 consecutive cytoreductive surgeries (CRS) and HIPEC and lessons learned with respect to the perioperative period.

During the last five years 150 consecutive patients underwent surgery with the intent to perform complete cytoreduction (CRS) and HIPEC. All patients underwent preoperative anesthesiological and cardiologic evaluation. Extraabdominal metastases were excluded and intraperitoneal tumor load was detected by computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or positron emission tomography (PET)-CT scan. After surgical exploration 50 (33%) patients were found to not be suitable for CRS and HIPEC due to either extensive intraoperative tumor load, retroperitoneal tumor infiltration or deep infiltration of the mesenteric axis.

In 100 consecutive patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of various origins (Table 1) cytoreductive surgery was performed with intraoperative hyperthermic chemotherapy. For colorectal or appendiceal cancer intraabdominal locally heated (42 Celcius) mitomycin C 25-35 mg/m2 was routinely administered for 90 min. For gastric or ovarian cancer cisplatin 50 mg/m2 was used. For gastric cancer a combination chemotherapy consisting of mitomycin and cisplatin was administered in some cases. Data were analyzed retrospectively.

| Tumor type | n |

| Colon | 21 |

| Rectal | 5 |

| Appendiceal | 10 |

| Ovarian | 33 |

| Pseudomyxoma | 13 |

| Stomach | 11 |

| Mesothelioma | 1 |

| Other | 6 |

| Tumor | n (%) |

| 1 | 5 (5) |

| 2 | 9 (9) |

| 3 | 44 (44) |

| 4 | 42 (42) |

| Nodes | n (%) |

| 0 | 33 (33) |

| 1 | 39 (39) |

| 2 | 24 (24) |

| 3 | 4 (4) |

After explorative laparotomy and complete adhesiolysis PCI score was determined, in particular with respect to the ligamentum teres, right upper suphrenic quadrant, space between the vena cava and liver segment 1, retro-splenic sulcus and bursa omentalis, which are most likely to be tumor-infiltrated. Then, after exclusion of contraindications, cytoreductive surgery was performed according to the technique described by Sugarbaker[1-8].

After maximal cytoreduction and reconstruction of intestinal continuity, if required, HIPEC was administered to the open abdomen for 90 min at 42 degrees Celsius. A rubber drain was routinely placed in the pelvis and an additional drain inserted in the left upper abdominal quadrant for splenectomy. Finally, the abdomen was closed with interrupted sutures.

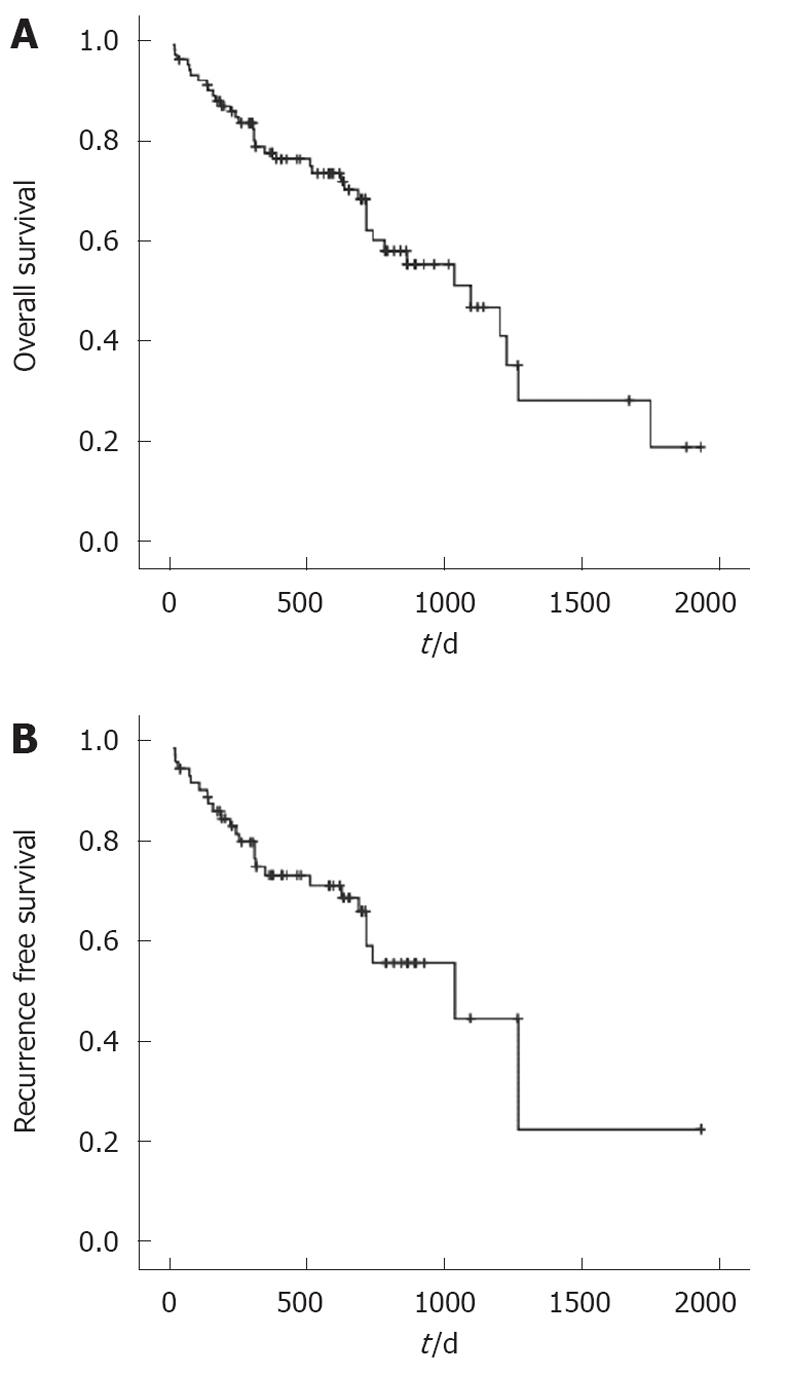

Data are presented as median (min-max) or n (%), unless otherwise stated. Qualitative differences were compared using the χ2 test, quantitative differences using the Mann-Whitney U test. Survival analysis was performed with the Kaplan-Meier method. For overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival, time to event was calculated as time from cytoreductive surgery until death or time to last contact, if the patient was alive. A P value less than 0.05 was considered significant. R was used for all statistical analysis[12].

Clinical characteristics, tumor types and intraoperative data are listed in Tables 1, 2 and 3. Most tumors treated were of ovarian (n = 33) or colorectal origin (n = 26). Median age was 54 (17-76) years. Median BMI was 24 cm/kg2. CRS with HIPEC was performed in 100 consecutive patients. The resection types are listed in Table 4. In 26 of the 50 patients without HIPEC an explorative laparotomy was performed. The other 24 patients underwent palliative bowel resection or debulking due to tumor obstruction. 66% of these patients died during follow-up with a 50% probability of survival within 224 d. Median operating time was 593 (178-1076) min. Median PCI was 17 (1-39). In 89% a radical resection (CC0/CC1) was achieved. Mitomycin C was used in 60% and Cisplatin in 32% of patients. In 5% a combination of Mitomycin C and Cisplatin was administered. A ureteral splint was perioperatively implanted in 17%. Intra- and postoperative complications are listed in Tables 5 and 6. The anastomotic leakage rate was 5.8%. HIPEC was not completed for 90 min in one patient due to cardiac arrhythmia. One patient died due to multi-organ failure. Leucopenia was observed in 29% of patients. Median hospital stay was 18 (3-105) d.

| Patients | n = 100 |

| Age (yr) | 54 (17-76) |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists [n (%)] | |

| 1 | 7 (7) |

| 2 | 52 (52) |

| 3 | 41 (41) |

| BMI (cm/kg2) | 24 (17-41) |

| Time to PC from primary diagnosis (d) | 365 (103-1009) |

| PCI score | 17 (1-39) |

| Operating time (min) | 593 (178-1076) |

| CC Status | n (%) |

| 0 | 56 (56) |

| 1 | 33 (33) |

| 2 | 11 (11) |

| HIPEC type | % |

| Mitomycin C | 60 |

| Cisplatin | 32 |

| Mitomycin C and Cisplatin | 5 |

| Other | 3 |

| Parietal peritonectomy | 90 |

| Gastrectomy | 18 |

| Ileo-coecal resection | 18 |

| Colonic resection | 19 |

| Anterior rectal resection | 35 |

| Right hemicolectomy | 28 |

| Sigmoideal resection | 11 |

| Small bowel resection | 28 |

| Omental resection | 33 |

| Cholecystectomy | 22 |

| Hysterectomy | 22 |

| Ovarectomy/adnexectomy | 14 |

| Splenectomy | 35 |

| Atypical liver resection | 9 |

| Pancreatic resection | 5 |

| Removal of part of the diaphragm | 15 |

| Tumor resection in the abdominal wall | 1 |

| Ureteral resection | 1 |

| Cumulative complications, n | 94 |

| 30-d mortality, n (%) | 1 |

| 90-d mortality, n (%) | 0 |

| Types of complication | n (%) |

| Cardiac | 1 (1) |

| Pneumonia | 5 (5) |

| Sepsis | 3 (3) |

| Thrombembolic | 9 (9) |

| Postoperative bleeding | 2 (2) |

| Ureter injury | 3 (3) |

| Wound infection | 21 (21) |

| Leukopenia | 29 (29) |

| Anastomotic leakage | 8 of 139 (5.8) |

| Compartment syndrome | 1 (1) |

| Transient paresthesia in the legs | 1 (1) |

| Pancreatic fistula | 0 |

| Reoperation due to complication | 21 (21) |

| DINDO complication classification | % |

| 0 | 52 |

| 1 | 23 |

| 2 | 10 |

| 3 | 3 |

| 4 | 11 |

| 5 | 1 |

Neither PCI, BMI nor age had a significant influence on perioperative complications according to the DINDO classification (Table 7). Median time of follow-up was 538 (17-1932) d.

| PCI < 20 | PCI≥20 | P value | Correlation coefficient | |

| DINDO 0 | 34 (55) | 18 (48) | 0.128 | 0.07 |

| DINDO 1-2 | 22 (35) | 10 (26) | ||

| DINDO 3-5 | 6 (10) | 10 (26) | ||

| Age < 65 | Age ≥ 65 | |||

| DINDO 0 | 45 (55) | 9 (50) | 0.917 | -0.0028 |

| DINDO 1-2 | 25 (30) | 6 (33) | ||

| DINDO 3-5 | 12 (15) | 3 (17) | ||

| BMI < 25 | BMI ≥ 25 | |||

| DINDO 0 | 35 (60) | 17 (41) | 0.075 | 0.19 |

| DINDO 1-2 | 17 (30) | 14 (33) | ||

| DINDO 3-5 | 6 (10) | 11 (26) |

Recurrence-free survival is shown in Figure 1B. Overall survival is shown in Figure 1A. In 9% Re-CRS with HIPEC was performed during the follow-up period.

CRS with HIPEC is now a procedure with the potential to cure selected patients suffering from PC[13-17]. PC can be considered a disease limited to the abdominal compartment, and based on this rationale maximal cytoreduction may be justified for various histological entities such as pseudomyxoma, ovarian cancer and colorectal cancer, etc., thus improving overall and recurrence-free survival[13-21].

Patient selection is certainly, as already mentioned, the “achilles heel” when including patients in this multimodal therapy. Radiological imaging estimates intraoperative tumor load, but reliable tumor identification in the critical regions such as the small bowel or ligamentum hepatoduodenale is still poor. Especially small lesions of about 1 cm or less are difficult to detect, even by PET-CT scan[22].

In this article we describe our first experiences with CRS and HIPEC. Since this procedure entails a certain morbidity, also due to long operating time, intraoperative chemotherapy and multivisceral resection, we attempted to detect risk factors for patient selection with a view to perioperative morbidity. The literature currently available gives no conclusive data on age or BMI of patients for the purpose of patient selection for this multimodal therapy.

Since it is generally known that numeric age does not correlate with biological age, it is not acceptable to generally exclude older patients who are in good condition. Moreover, patients with a high BMI are often viewed negatively, because they are more challenging to operate and have a greater risk for perioperative complications.

Additionally, one of the main prognostic factors is PCI and when it exceeds 20 in colorectal cancers no survival benefit is achieved. However, for other entities it is still unclear and in pseudomyxoma the completeness of cytoreduction is the only prognostic factor, not tumor load.

From our results we concluded that tumor load, age and BMI had no significant impact on the perioperative complication rate according to the DINDO classification. Therefore, if desired, a biologically young patient should be included in this therapy if CC0/CC1 resection appears possible. We therefore hypothesize that the probability to achieve a CC0/CC1 resection should be the determining criterion for selection, and not PCI. Patients with a BMI over 25 had complication rates similar to those of patients with a BMI under 25. At any rate, we recommend that caution be exercised with superobese patients, because they were not represented in this study.

In obese patients with a low PCI, a laparoscopic approach with HIPEC might be an option and should be discussed[23].

For patients with a high PCI this also seems valuable. The results of this study show that from the standpoint of postoperative morbidity more patients could be included in this therapy. Resectability should remain the main criteria for performing CRS and HIPEC.

In the beginning we generously applied a ureteral splint during peritonectomy for better orientation in patients with pelvic recurrence. Because of extensive pre- and postoperative pain and the questionable necessity of the splint during the operation we abandoned ureteral splinting completely in patients without hydronephrosis. In one case we had to perform a ureteral resection and end-to-end anastomosis because of tumor infiltration.

Our anastomotic leakage rate of 5.8% is acceptable and comparable with that of the current literature[10]. However, we tended to avoid anastomoses or stomas in favor of meticulous cleaning of the small bowel and large bowel of tumor seedings whenever possible, especially in the most recent patients. Only four patients received a loop ileostomy after anterior rectal resection, two received a terminal ileostomy after colectomy and four patients a terminal colostomy. In our opinion resection of the colon should not be performed according to oncologic criteria with removal of a maximum of lymph nodes, except when there is a synchronous PC of colorectal cancer. More importantly, all macroscopically visible tumor seedings must be removed and the organs should be preserved whenever possible.

Most recurrences occurred in the right upper quadrant or in the retroperitoneum (data not shown). This might have been induced by the large wound surfaces and the increasing risk for tumor adherence[24]. This observation has been known for a long time[25-27]. In this regard, CRS should be performed only in the tumor-affected peritoneum and never in healthy tissue. Nonetheless, it is sometimes easier to begin with the parietal peritonectomy in the healthy region, for example by removing the peritoneum of the whole pelvis and not only the affected region in the Douglas space.

In the summary of the decision to include or not include a patient in this multimodal therapy is based on a variety of factors and should be done only at centers offering interdisciplinary evaluation by internal medicine specialists, surgical oncologists, anesthetists and radiologists. Lastly, the decision should be taken individually for each patient and high PCI, BMI or age should not be an exclusion criterion per se with regard to perioperative morbidity.

Perioperative patient morbidity/mortality after cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) is a major concern in the selection process for this multimodal therapy.

Of 150 patients 100 were treated with cytoreductive surgery and HIPEC and retrospectively analyzed. Clinical and postoperative follow-up data were evaluated. Body mass index (BMI), age and peritoneal carcinomatosis index (PCI) were chosen as selection criteria with regard to perioperative morbidity.

Neither PCI, age nor BMI was a risk factor for postoperative complications/ outcome according to the Dindo classification. The decision to include or not to include a patient in this multimodal therapy regimen is based on a variety of factors and should be made only at centers offering interdisciplinary evaluation by internal medicine specialists, surgical oncologists, anesthesiologists and radiologists. Finally, the decision should be made individually for each patient and high PCI, BMI or age should not be an a priori exclusion criterion with regard to perioperative morbidity.

The study results suggest that a high PCI, BMI or advanced age itself are not a contraindication for this multimodal therapy concerning perioperative morbidity.

HIPEC is administered with 42 degrees Celcius for 90 min; PCI describes the intraperitoenal tumor load and was developed by Professor Sugarbaker.

This is a good descriptive study in which authors analyze perioperative patient morbidity/mortality and outcome after CRS and HIPEC. The results are interesting and suggest that patient selection remains the most important issue. Neither PCI, age nor BMI alone should be an exclusion criterion for this multimodal therapy.

| 1. | Sugarbaker PH. Peritonectomy procedures. Cancer Treat Res. 2007;134:247-264. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Sugarbaker PH. Surgical management of peritoneal carcinosis: diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1988;373:189-196. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Sugarbaker PH, Landy D, Pascal R. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal carcinomatosis from colonic or appendiceal cystadenocarcinoma: rationale and results of treatment. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1990;354B:141-170. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Sugarbaker PH. Surgical treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis: 1988 Du Pont lecture. Can J Surg. 1989;32:164-170. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Sugarbaker PH. Patient selection and treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis from colorectal and appendiceal cancer. World J Surg. 1995;19:235-240. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Hallenbeck P, Sanniez CK, Ryan AB, Neiley B, Sugarbaker PH. Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Treatment for peritoneal carcinomatosis. AORN J. 1992;56:50-57; 60-72. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Sugarbaker PH, Chang D, Koslowe P. Prognostic features for peritoneal carcinomatosis in colorectal and appendiceal cancer patients when treated by cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Cancer Treat Res. 1996;81:89-104. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Sugarbaker PH. Peritonectomy procedures. Cancer Treat Res. 1996;82:235-253. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Königsrainer I, Aschoff P, Zieker D, Beckert S, Glatzle J, Pfannenberg C, Miller S, Hartmann JT, Schroeder TH, Brücher BL. [Selection criteria for peritonectomy with hyperthermic intraoperative chemotherapy (HIPEC) in peritoneal carcinomatosis]. Zentralbl Chir. 2008;133:468-472. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Glehen O, Gilly FN, Boutitie F, Bereder JM, Quenet F, Sideris L, Mansvelt B, Lorimier G, Msika S, Elias D. Toward curative treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis from nonovarian origin by cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy: a multi-institutional study of 1,290 patients. Cancer. 2010;116:5608-5618. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-213. [PubMed] |

| 12. | R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing 2010; Available from: http//www.r-project.org/. |

| 13. | Glehen O, Mohamed F, Gilly FN. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from digestive tract cancer: new management by cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5:219-228. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Sugarbaker PH. New standard of care for appendiceal epithelial neoplasms and pseudomyxoma peritonei syndrome? Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:69-76. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Verwaal VJ, Bruin S, Boot H, van Slooten G, van Tinteren H. 8-year follow-up of randomized trial: cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy versus systemic chemotherapy in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2426-2432. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Yan TD, Morris DL. Cytoreductive surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for isolated colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis: experimental therapy or standard of care? Ann Surg. 2008;248:829-835. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Yan TD, Welch L, Black D, Sugarbaker PH. A systematic review on the efficacy of cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy for diffuse malignancy peritoneal mesothelioma. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:827-834. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Deraco M, Nonaka D, Baratti D, Casali P, Rosai J, Younan R, Salvatore A, Cabras Ad AD, Kusamura S. Prognostic analysis of clinicopathologic factors in 49 patients with diffuse malignant peritoneal mesothelioma treated with cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal hyperthermic perfusion. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:229-237. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Chua TC, Robertson G, Liauw W, Farrell R, Yan TD, Morris DL. Intraoperative hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy after cytoreductive surgery in ovarian cancer peritoneal carcinomatosis: systematic review of current results. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135:1637-1645. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Di Giorgio A, Naticchioni E, Biacchi D, Sibio S, Accarpio F, Rocco M, Tarquini S, Di Seri M, Ciardi A, Montruccoli D. Cytoreductive surgery (peritonectomy procedures) combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) in the treatment of diffuse peritoneal carcinomatosis from ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2008;113:315-325. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Glehen O, Schreiber V, Cotte E, Sayag-Beaujard AC, Osinsky D, Freyer G, François Y, Vignal J, Gilly FN. Cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemohyperthermia for peritoneal carcinomatosis arising from gastric cancer. Arch Surg. 2004;139:20-26. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Pfannenberg C, Königsrainer I, Aschoff P, Oksüz MO, Zieker D, Beckert S, Symons S, Nieselt K, Glatzle J, Weyhern CV. (18)F-FDG-PET/CT to select patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis for cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1295-1303. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Esquivel J, Averbach A, Chua TC. Laparoscopic cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in patients with limited peritoneal surface malignancies: feasibility, morbidity and outcome in an early experience. Ann Surg. 2011;253:764-768. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Königsrainer I, Zieker D, Beckert S, von Weyhern C, Löb S, Falch C, Brücher BL, Königsrainer A, Glatzle J. Local peritonectomy highly attracts free floating intraperitoneal colorectal tumour cells in a rat model. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2009;23:371-378. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Fisher B, Fisher ER, Feduska N. Trauma and the localization of tumor cells. Cancer. 1967;20:23-30. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Agostino D, Cliffton EE. Organ localization and the effect of trauma on the fate of circulating cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1965;25:1728-1732. [PubMed] |

Peer reviewer: Jesus Esquivel, Professor, St Agnes Hosp, 900 Caton Ave, Baltimore, MD 21229, United States

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN