Published online Apr 28, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i16.1991

Revised: November 24, 2011

Accepted: December 15, 2011

Published online: April 28, 2012

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is a small-vessel vasculitis mediated by IgA-immune complex deposition. It is characterized by the clinical tetrad of non-thrombocytopenic palpable purpura, abdominal pain, arthritis and renal involvement. The diagnosis of HSP is difficult, especially when abdominal symptoms precede cutaneous lesions. We report a rare case of paroxysmal drastic abdominal pain with gastrointestinal bleeding presented in HSP. The diagnosis was verified by renal damage and the occurrence of purpura.

- Citation: Chen XL, Tian H, Li JZ, Tao J, Tang H, Li Y, Wu B. Paroxysmal drastic abdominal pain with tardive cutaneous lesions presenting in Henoch-Schönlein purpura. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(16): 1991-1995

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i16/1991.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i16.1991

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP) is the most common systemic vasculitis in children. The diagnostic criteria include palpable purpura with at least one other manifestation including abdominal pain, IgA deposition, arthritis or arthralgia, and renal involvement[1,2]. Immune complex deposits induce necrosis of the walls of small- and medium-sized arteries with infiltration of the tissue by neutrophils and the deposition of nuclear fragments, a process called leukocytoclastic vasculitis[3]. It is often associated with infection, certain medications, or tumors. It may coexist with or mimic Crohn’s disease[4]. Periumbilical and epigastric pain worsen with meals due to bowel angina. Bleeding is usually occult or, less commonly, associated with melena. Intussusception is the most common surgical complication. Perforations, usually ileal, may occur spontaneously or be associated with intussusception. An ultrasound, recommended as the first diagnostic test, and computed tomography (CT) scans may reveal intussusception and asymmetric bowel wall thickening mainly involving the jejunum and ileum. There are a range of possible endoscopic findings including gastritis, duodenitis, ulceration, and purpura, with the second portion of the duodenum characteristically being involved more than the bulb. Intestinal biopsies show IgA deposition and leukocytoclastic vasculitis in the submucosal vessels[3]. Superficial biopsies may show inflammation, ulceration, edema, hemorrhage, and vascular congestion, presumably due to vasculitis-induced mucosal ischemia[5]. The efficacy of corticosteroids in preventing severe complications or relapses is controversial. The majority of patients, however, improve spontaneously.

A 15-year-old boy was referred from another hospital to our institution in November 2010. He was previously healthy without any remarkable past medical history and denied any recent non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use or illicit drug use. He complained of progressive epigastrium and periumbilical pain, nausea and mild diarrhea with melena that had lasted for 3 wk. No rash was noticed on the skin. On physical examination, his vital signs were normal, except for epigastric pressing pain and suspicious rebound pain. Importantly, no skin rash was observed.

Laboratory blood examinations showed the following indexes (normal range in parentheses): hemoglobin, 109 g/L (120-140 g/L); peripheral white cell count, 20.09 × 109/L (5-10 × 109/L); neutrophils, 83.7% (40%-60%); peripheral red cell count, 5.43 × 1012/L (4.0-4.5 × 1012/L); platelet count, 267 × 109/L (100-300 × 109/L); C-reactive protein, 68.0 mg/L (0-6.0 mg/L); erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 14 mm/h (0-20 mm/h); albumin, 24.8 mg/L (36-51 mg/L); and total immunoglobulin (Ig), 17.6 mg/L (25.0-35.0 mg/L); IgA, 2.292 g/L (0.7-3.3 g/L); total bilirubin, 6.3 μmol/L (4-23.9 μmol/L); alkaline phosphatase, 38 U/L (35-125 U/L); c-glutamyl transpeptidase, 12 U/L (7-50 U/L); aspartate aminotransferase, 15 U/L (14-40 U/L); alanine aminotransferase, 21 U/L (5-35 U/L); prothrombin time, 13.8 s (11.0-14.5 s); creatinine, 453 μmol/L (31.8-91.0 μmol/L), and blood urine nitrogen, 33 g/L (31.8-91.0 g/L). A routine urine test did not reveal any RBCs or proteins on the first day of hospitalization. Autoimmune-related indicators and tuberculosis (TB)-related antibodies were not found in the blood, and the TB-purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test was negative. Hepatitis B and C markers were also negative.

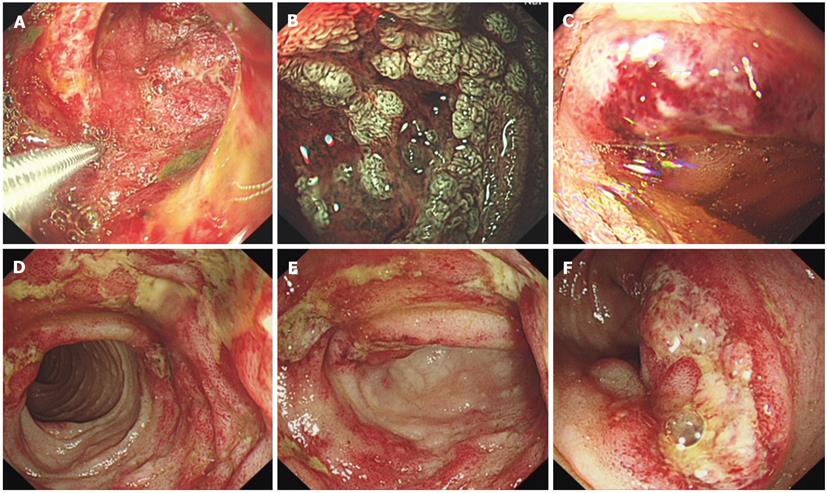

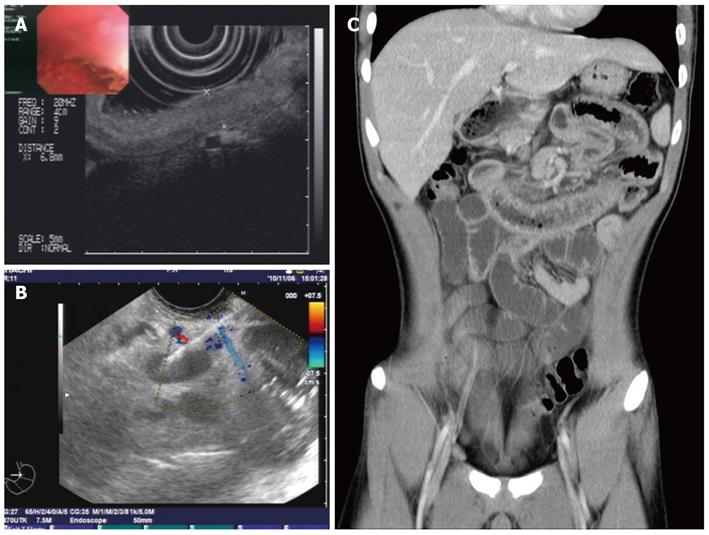

Plain abdominal radiography revealed incomplete small-intestine obstruction. Gastroscopy and colonoscopy revealed some mucosal swelling, erosion, and active ulcers with hemorrhage in the duodenum and terminal ileum (Figure 1), but not in the stomach or colon. The histopathology of duodenal mucosa and ileal mucosa showed a chronic mucosal inflammation with necrosis (data not shown). Ultrasound endoscopy (EUS) and abdominal CT examinations revealed the presence of thickened intestinal mucosa with submucosal hemorrhage and enlarged mesenteric and retroperitoneal lymph nodes (Figure 2). EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) biopsy of the enlarged lymph nodes revealed an inflammatory reaction without lymphoma (data not shown). Positron emission tomography and computed tomography also indicated that the enlarged lymph nodes were a sign of inflammation, not of a malignant tumor (data not shown).

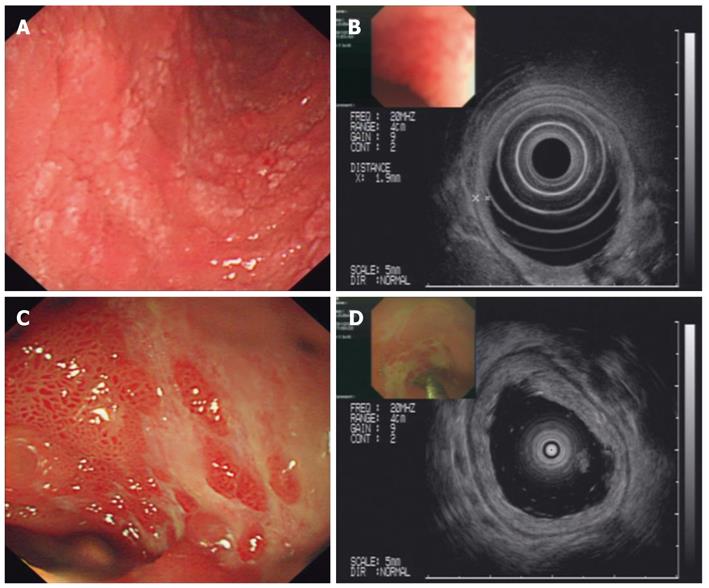

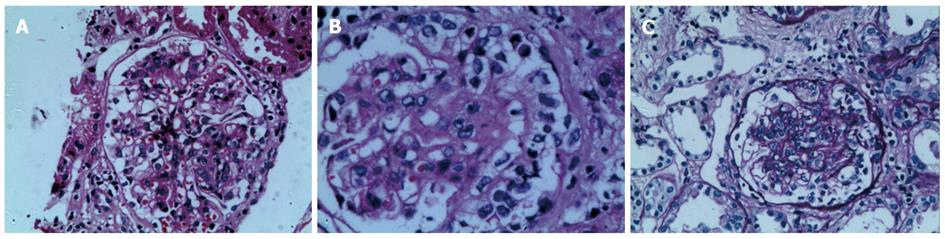

During the first two weeks of hospitalization, the patient accepted treatment with antibiotics and a proton pump inhibitor (pantoprazole 40 mg, twice daily), but his abdominal pain was not alleviated, and the paroxysmal abdominal pain worsened progressively. After two weeks of hospitalization, the patient’s urine test revealed significant albuminuria. Levels of urine albumin increased to 1170 mg/L (0-20 mg/L), and 24-h total urine protein increased to 4.08 g (0-0.12 g). Further, the urine protein analysis showed a remarkable increase in kappa and lambda light chain levels to 62.5 mg/L (0-7.1 mg/L) and 28.8 mg/L (0-3.9 mg/L), respectively. The level of urine IgA increased to 102 mg/L (0-17.5 mg/L). Therefore, the diagnoses were considered to be an autoimmune-related disorder such as Crohn’s disease and multiple vasculitis or lymphoma. The patient was treated with corticosteroid therapy in the form of intravenous methylprednisolone (40 mg/d). By the next day, the drastic abdominal pain was rapidly alleviated, and the melena also gradually disappeared. After one week of methylprednisolone therapy, the treatment was changed to the oral administration of prednisolone therapy (30 mg/d). During the fourth week of corticosteroid therapy, palpable purpura appeared over the patient’s lower extremities. A diagnosis of HSP was ultimately established. After four weeks of corticosteroid treatment, endoscopy and EUS showed that the patient’s mucosal damage had improved significantly, and the mucosal edema was observably mitigated (Figure 3). A percutaneous renal biopsy revealed focal segmental endocapillary crescent-like proliferation (Figure 4). Positive immunofluorescence staining for mesangial IgA was also observed (data not shown). The histopathology of renal biopsies supported the diagnosis of anaphylactoid purpura nephritis (APN), which was classified as ISKDC IV according to the classification criteria of the International Study of Kidney Disease in Children[6].

HSP is a form of blood vessel inflammation or vasculitis, also referred to as anaphylactoid purpura. Vasculitis is involved in many conditions[1]. Each of the forms of vasculitis tends to involve certain characteristic blood vessels. HSP is a multisystem disorder predominantly affecting the skin, joints, gastrointestinal tract and kidneys, but other organs can be affected as well. Neurological, pulmonary, cardiac and genitourinary complications rarely occur. HSP results in a skin rash (most prominent over the buttocks and behind the lower extremities) associated with joint inflammation (arthritis) and sometimes cramping pain in the abdomen. The condition primarily affects children (over 90% of cases); occurrences in adults have rarely been reported (3.4 to 14.3 cases per million)[3]. HSP occurs most often in the spring and frequently follows an infection of the throat or breathing passages. HSP seems to represent an unusual reaction of the body’s immune system in response to this infection (either bacterial or viral). In addition to infection, drugs can trigger the condition. HSP occurs most commonly in children, but people of all age groups can be affected.

HSP is usually diagnosed based on skin, joint, and kidney findings. Throat culture, urinalysis, and blood tests for inflammation and kidney function are used to determine the diagnosis. A biopsy of the skin, and less commonly, the kidneys, can be used to demonstrate the presence of vasculitis. Special staining techniques (direct immunofluorescence) of the biopsy specimen can be used to document antibody deposits of IgA in the blood vessels of involved tissue. Renal involvement is rarely severe and is observed in approximately 50% of patients[1,2].

According to the diagnostic criteria of the European League against Rheumatism and the Paediatric Rheumatology European Society published in 2006, palpable purpura often presents with one of the following: diffuse abdominal pain, a biopsy showing predominant IgA expression, acute arthritis/arthralgia, or renal involvement defined as any hematuria or proteinuria. However, when gastrointestinal manifestations occur alone or precede dermatological or renal disease, the diagnosis is difficult[7,8]. Typically, palpable purpura will not precede renal involvement[9,10]. However, in this case, purpura occurred during the seventh week of onset, and renal involvement occurred during the fourth week of onset, which delayed the diagnosis of HSP. HPS may coexist with Crohn’s disease or mimic its symptoms (e.g., ileitis or ulcerative colitis)[4,11,12]. The clinical manifestations of HSP in the gastrointestinal tract are similar to gastrointestinal tuberculosis, lymphoma, inflammatory bowel disease, and other autoimmune disorders, which renders the diagnosis of HSP difficult. In this case, paroxysmal drastic abdominal pain with gastrointestinal bleeding was presented as the princeps clinical situation. The characteristic endoscopic findings included diffuse mucosal redness, small ring-like petechiae, hemorrhagic erosions and ulcers. These manifestations created confusion until the diagnosis of HSP was verified by the presence of renal damage and purpura. Mucosal lesions develop anywhere within the gastrointestinal tract. The small intestine is considered to be the most frequently affected site, and duodenal involvement was more prominent in the second part of the duodenum than in the bulb and stomach or colon.

Gastrointestinal involvement is frequent in HSP. The diagnosis of HSP may be difficult, especially when abdominal symptoms precede the characteristic palpable purpura. Typical endoscopic findings may alert gastroenterologists to the need to consider this diagnosis early in treatment and thus avoid unnecessary laparotomy.

| 2. | Saulsbury FT. Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2010;22:598-602. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Jithpratuck W, Elshenawy Y, Saleh H, Youngberg G, Chi DS, Krishnaswamy G. The clinical implications of adult-onset henoch-schonelin purpura. Clin Mol Allergy. 2011;9:9. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Rahman FZ, Takhar GK, Roy O, Shepherd A, Bloom SL, McCartney SA. Henoch-Schönlein purpura complicating adalimumab therapy for Crohn's disease. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2010;1:119-122. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Ebert EC. Gastrointestinal manifestations of Henoch-Schonlein Purpura. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2011-2019. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Lorber M. Henoch-Shoenlein Purpura. Diagnostic criteria in autoimmune diseases. Totowa: Humana Press 2008; 133-136. |

| 7. | Cheungpasitporn W, Jirajariyavej T, Howarth CB, Rosen RM. Henoch-Schönlein purpura in an older man presenting as rectal bleeding and IgA mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2011;5:364. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Nishiyama R, Nakajima N, Ogihara A, Oota S, Kobayashi S, Yokoyama K, Oonishi M, Miyamoto S, Akai Y, Watanabe T. Endoscope images of Schönlein-Henoch purpura. Digestion. 2008;77:236-241. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Davin JC. Henoch-Schonlein purpura nephritis: pathophysiology, treatment, and future strategy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:679-689. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Sohagia AB, Gunturu SG, Tong TR, Hertan HI. Henoch-schonlein purpura-a case report and review of the literature. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2010;2010:597648. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Giménez-Esparza Vich JA, Argüelles BF, Martin IH, Gutierrez Fernández MJ, Porras Vivas JJ. Recurrence of Henoch-Schönlein purpura in association with colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:492-493. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Al-Toma AA, Brink MA, Hagen EC. Henoch-Schönlein purpura presenting as terminal ileitis and complicated by thrombotic microangiopathy. Eur J Intern Med. 2005;16:510-512. [PubMed] |

Peer reviewers: Guang-Yin Xu, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston 77555-0655, United States; Bassam N Abboud, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of General Surgery, Hote-Dieu de France Hospital, Alfred Naccache Street, Beirut 16-6830, Lebanon

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN