Published online Dec 21, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i47.5227

Revised: April 19, 2011

Accepted: April 26, 2011

Published online: December 21, 2011

The presence of hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG) is associated with numerous diseases, and has been regarded as a serious, even catastrophic condition. However, anecdotal reports mention that some patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), who developed HPVG after diagnostic examinations of the colon, were successfully managed with antibiotic therapy and have followed benign courses. In contrast, among IBD patients, the development of HPVG is rarely caused by enterovenous fistula. We describe a 32-year-old man with Crohn’s ileocolitis who presented with hypotension and fever associated with HPVG, as well as superior mesenteric vein thrombosis, possibly caused by enterovenous fistula, who was successfully managed by surgery. We also review the literature concerning portal venous gas associated with Crohn’s disease.

- Citation: Lim JW, Kim KJ, Ye BD, Byeon JS, Myung SJ, Yang SK, Kim JH. Enterovenous fistulization: A rare complication of Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(47): 5227-5230

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i47/5227.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i47.5227

Hepatic portal venous gas (HPVG), as first described in 1955[1], has been reported in many illnesses, ranging from benign conditions to potentially lethal diseases that require urgent surgical intervention[2]. Overall mortality depends on the underlying disease[3].

Among the various diseases, HPVG associated with Crohn’s disease (CD) has rarely been described. With regard to the treatment of patients with CD complicated with HPVG, some anecdotal reports suggested that conservative treatment with antibiotics might be effective. However, early recognition and urgent operative intervention at the time of presentation are still important in patients with complicated CD. We report a 32-year-old patient with CD who presented with fever and hypotension associated with HPVG and mesenteric vein thrombosis who was successfully managed surgically. To our knowledge, this is the first report of HPVG and mesenteric vein thrombosis possibly caused by enterovenous fistula complicated by CD in South Korea. The literature concerning PVG associated with CD is also reviewed.

A 32-year-old man was referred for evaluation of mesenteric and portal venous gas detected by abdominal computerized tomography (CT). The patient had complained of lower abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and fever. He was diagnosed with CD complicated by perianal fistula 12 years prior to admission, and was treated with azathioprine (25 mg/d) and 5-aminosalicylate (ASA; 3.2 g/d). He had been in his usual state of health on azathioprine and ASA until abdominal pain developed 21 d before admission at which time budesonide (9 mg/d) was added to his regimen of azathioprine and ASA. He continued on all three medications for three weeks until developing fever 2 d prior to admission. At that time, an abdominal CT showed mesenteric and portal venous gas. He was then referred to this hospital.

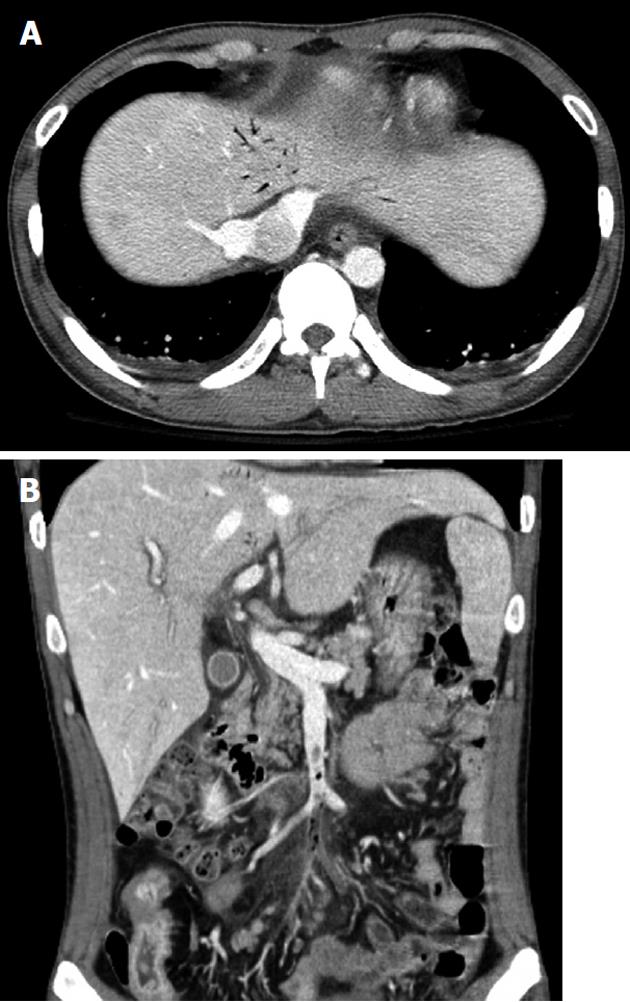

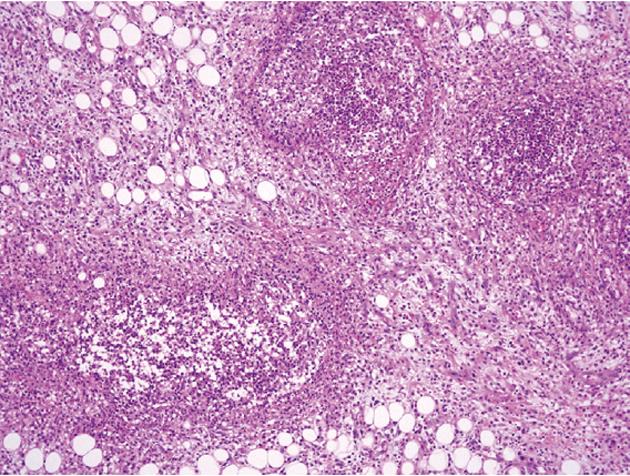

At admission, his body temperature was 38.5 °C, blood pressure was 82/47 mmHg, and pulse rate was 105 beats per minute. There was moderate tenderness on the lower abdomen, but no abdominal distension or signs of peritoneal irritation. His white blood cell count was 4600/mm3 (normal range 4000-10 000/mm3) with 87% segmented forms. Protein was 4.9 g/dL (normal range 3.5-5.2 g/dL), albumin was 2.1 g/dL (normal range 6.0-8.5 g/dL), C-reactive protein was 21.19 mg/dL (normal range < 0.3 mg/dL), prothrombin time was 1.41 international normalized ratio (INR) (normal range 0.84-1.21 INR), and activated partial thromboplastin time was 37.3 s (normal range 26.3-39.4 s). Plain abdominal films were unremarkable. Abdominopelvic CT revealed the presence of air bubbles in the hepatic portal vein, superior mesenteric vein (SMV), and its contributaries. Intravenous thrombi were also noted (Figure 1). With regard to the bowel, multiple segments of the small bowel were thickened in the mid to the distal ileum and distal colon, especially in a 20 cm segment of the mid-ileum, near the mesenteric venous gas (Figure 2). The abdominopelvic CT findings were compatible with CD complicated with thrombophlebitis of the SMV. Hence, an explorative laparotomy was performed. At operation, a small amount of serous ascites was noted throughout the peritoneal cavity with multiple strictures and areas of inflammation which were also noted along the mid to distal ileum. Moreover, a short segment of mid-ileum showed phlegmonous change. Ileocecal resection was performed. Pathologic examination disclosed transmural inflammation with lymphoid aggregates, multiple microgranulomas and a fistulous tract. In addition, many neutrophils had accumulated in the intravascular space, suggesting the presence of an enterovenous fistula (Figure 3).

After surgery, the patient had an uneventful recovery and was discharged 9 d post surgery. The patient has been on 3 g of mesalazine and 25 mg of 6-mercaptopurine for his colonic disease and has been well for 4 mo after surgery.

HPVG has been reported in association with numerous conditions in adults, including intestinal ischemia or necrosis[4], intra-abdominal abscess[5], diverticulitis[6], pneumatosis intestinalis[7], and blunt trauma[8]. When HPVG occurred in association with necrotic bowel, the overall mortality rate rose to about 75%[9]. Thus, in the past, HPVG has been considered as an indicator for urgent surgical intervention with a poor prognosis. However, the development of highly advanced imaging techniques enables earlier detection of potentially severe pathologies, such as bowel ischemia, and allows prompt diagnosis and treatment, which results in significantly reduced mortality rates[10]. HPVG is not always a surgical condition, and its treatment should be based on the underlying disease and the patient’s current clinical condition. HPVG in patients with inflammatory bowel disease can be caused by mucosal damage alone, or can occur in combination with bowel distension, sepsis, invasion by gas-producing bacteria, or after colonoscopy, upper gastrointestinal barium examination, barium enema or blunt abdominal trauma. Not all of these conditions require surgical intervention, especially in the absence of peritoneal signs or free gas in the peritoneal space[2].

The prognosis is related to the pathology itself and is not influenced by the presence of HPVG. Among 182 case studies reported by Kinoshita et al[2], patients with ulcerative colitis or CD comprised 4% of the total. To our knowledge, 21 cases of PVG associated with CD were reported in the English literature[11-13].

The formation of HPVG in patients with CD can be explained by the following hypothesis; first, elevated intracolonic pressure can permit bowel gas or gas-forming bacteria to gain access to the portal venous circulation. Elevated intracolonic pressure caused by blunt abdominal trauma, or by diagnostic procedures such as colonoscopy or barium enema occurred in 2 and 6 out of 21 patients, respectively, that had relatively benign clinical courses and rarely needed surgical intervention; only one of the eight required surgery. Second, the enterovenous fistula, which is an extremely rare complication of CD, can directly transfer bowel gas to the portal venous system. To date, HPVG associated with enterovenous fistula has been reported in 2 patients[14,15]. Two CD patients with enterovenous fistula required surgery, and one died due to sepsis. Third, HPVG can be the result of mucosal injury and sepsis associated with bowel inflammation and portal pyemia. Mucosal damage secondary to bowel inflammation provides an entry for intraluminal gas into the portal venous system. In addition, sepsis alone without necrotic bowel can be the cause of HPVG[9]. The remaining 11 patients included in that study, who had no identifiable predisposing factors, may have developed HPVG by this mechanism.

In our patient, the second mechanism is the most plausible explanation for HPVG based on surgical pathology and CT findings. Although there was no definite communication between bowel and vessel shown on the abdominal CT scan, a thrombosed vessel along with a thickened bowel suggests possible communication. The fistula between the small bowel and small branches of the superior mesenteric vein was not easily identified on CT because of its small size. Furthermore, histopathology showed many neutrophils accumulated in the intravascular space, an occluded small mesenteric vein caused by inflammatory thrombus, and no evidence of bowel ischemia. Based on the clinical features, histopathology, and imaging findings, mesenteric venous thrombosis was not a plausible diagnosis.

In eleven patients without a predisposing condition, eight (73%) presented with signs of intra-abdominal catastrophe or systemic toxicity and required surgery. One of eight died of disseminated cytomegalovirus infection, and the remaining three out these eleven patients were conservatively managed.

Two cases were reported with a combination of PVG and thrombophlebitis of the portal vein or SMV. These patients presented with septic shock and needed surgical treatment[11,16]. Although PVG itself is not a prognostic indicator, PVG combined with thrombophlebitis of the portal or mesenteric veins can be regarded as an indicator of poor prognosis.

Although the incidence of CD in Asians is still much lower than in Western patients, recent studies have reported that the incidence of CD in Asian populations is gradually increasing[17,18]. As the number of patients with CD increases, the proportion of complicated CD patients also increases. Although PVG accompanied by mesenteric venous thrombosis occurs very rarely in patients with CD, it complicates treatment decisions for the gastroenterologist. Thus, we should exercise caution regarding the clinical management in cases of CD with HPVG. HPVG associated with CD does not always mandate surgical intervention, especially in the absence of peritoneal signs or free intraperitoneal gas. Those patients found to have significant intestinal pathology, as in this case, as seen from imaging studies, or all other symptomatic patients who do not improve after medical treatment, should undergo urgent laparotomy[10]. The clinical course seems to be associated with predisposing factors, such as in this case, where hypotension and fever necessitated urgent surgery.

In conclusion, the finding of PVG is not always an indication for surgical intervention in CD, but PVG caused by enterovenous fistula requires urgent surgical treatment.

| 1. | Wolfe JN, Evans WA. Gas in the portal veins of the liver in infants; a roentgenographic demonstration with postmortem anatomical correlation. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1955;74:486-488. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Kinoshita H, Shinozaki M, Tanimura H, Umemoto Y, Sakaguchi S, Takifuji K, Kawasaki S, Hayashi H, Yamaue H. Clinical features and management of hepatic portal venous gas: four case reports and cumulative review of the literature. Arch Surg. 2001;136:1410-1414. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Nelson AL, Millington TM, Sahani D, Chung RT, Bauer C, Hertl M, Warshaw AL, Conrad C. Hepatic portal venous gas: the ABCs of management. Arch Surg. 2009;144:575-581; discussion 581. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Traverso LW. Is hepatic portal venous gas an indication for exploratory laparotomy? Arch Surg. 1981;116:936-938. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Bach MC, Anderson LG, Martin TA, McAfee RE. Gas in the hepatic portal venous system. A diagnostic clue to an occult intra-abdominal abscess. Arch Intern Med. 1982;142:1725-1726. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Cambria RP, Margolies MN. Hepatic portal venous gas in diverticulitis: survival in a steroid-treated patient. Arch Surg. 1982;117:834-835. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Dodds WJ, Stewart ET, Goldberg HI. Pneumatosis intestinalis associated with hepatic portal venous gas. Am J Dig Dis. 1976;21:992-995. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Vauthey JN, Matthews CC. Portal vein air embolization after blunt abdominal trauma. Am Surg. 1988;54:586-588. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Liebman PR, Patten MT, Manny J, Benfield JR, Hechtman HB. Hepatic--portal venous gas in adults: etiology, pathophysiology and clinical significance. Ann Surg. 1978;187:281-287. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Brandon T, Bogard B, ReMine S, Urban L. Early recognition of hepatic portal vein gas on CT with appropriate surgical intervention improves patient survival. Curr Surg. 2000;57:452-455. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Ng SS, Yiu RY, Lee JF, Li JC, Leung KL. Portal venous gas and thrombosis in a Chinese patient with fulminant Crohn's colitis: a case report with literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5582-5586. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Alqahtani S, Coffin CS, Burak K, Chen F, MacGregor J, Beck P. Hepatic portal venous gas: a report of two cases and a review of the epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis and approach to management. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007;21:309-313. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Salyers WJ, Mansour A. Portal venous gas following colonoscopy and small bowel follow-through in a patient with Crohn's disease. Endoscopy. 2007;39 Suppl 1:E130. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Ajzen SA, Gibney RG, Cooperberg PL, Scudamore CH, Miller RR. Enterovenous fistula: unusual complication of Crohn disease. Radiology. 1988;166:745-746. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Reiner L, Freed A, Bloom A. Enterovenous fistulization in Crohn's disease. JAMA. 1978;239:130-132. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Kluge S, Hahn KE, Lund CH, Gocht A, Kreymann G. [Pylephlebitis with air in the portal vein system. An unusual focus in a patient with sepsis]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2003;128:1391-1394. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Thia KT, Loftus EV, Sandborn WJ, Yang SK. An update on the epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:3167-3182. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Yang SK, Yun S, Kim JH, Park JY, Kim HY, Kim YH, Chang DK, Kim JS, Song IS, Park JB. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in the Songpa-Kangdong district, Seoul, Korea, 1986-2005: a KASID study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:542-549. [PubMed] |

Peer reviewer: Jay Pravda, MD, Inflammatory Disease Re-search Center, Gainesville, FL 32614-2181, United States

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Li JY