Published online Nov 21, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i43.4787

Revised: June 16, 2011

Accepted: June 23, 2011

Published online: November 21, 2011

AIM: To evaluate clinical validity of the compression anastomosis ring (CAR™ 27) anastomosis in left-sided colonic resection.

METHODS: A non-randomized prospective data collection was performed for patients undergoing an elective left-sided colon resection, followed by an anastomosis using the CAR™ 27 between November 2009 and January 2011. Eligibility criteria of the use of the CAR™ 27 were anastomoses between the colon and at or above the intraperitoneal rectum. The primary short-term clinical endpoint, rate of anastomotic leakage, and other clinical outcomes, including intra- and postoperative complications, length of operation time and hospital stay, and the ring elimination time were evaluated.

RESULTS: A total of 79 patients (male, 43; median age, 64 years) underwent an elective left-sided colon resection, followed by an anastomosis using the CAR™ 27. Colectomy was performed laparoscopically in 70 patients, in whom two patients converted to open procedure (2.9%). There was no surgical mortality. As an intraoperative complication, total disruption of the anastomosis occurred by premature enforced tension on the proximal segment of the anastomosis in one patient. The ring was removed and another new CAR™ 27 anastomosis was constructed. One patient with sigmoid colon cancer showed postoperative anastomotic leakage after 6 d postoperatively and temporary diverting ileostomy was performed. Exact date of expulsion of the ring could not be recorded because most patients were not aware that the ring had been expelled. No patients manifested clinical symptoms of anastomotic stricture.

CONCLUSION: Short-term evaluation of the CAR™ 27 anastomosis in elective left colectomy suggested it to be a safe and efficacious alternative to the standard hand-sewn or stapling technique.

- Citation: Lee JY, Woo JH, Choi HJ, Park KJ, Roh YH, Kim KH, Lee HY. Early experience of the compression anastomosis ring (CARTM 27) in left-sided colon resection. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(43): 4787-4792

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i43/4787.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i43.4787

A well-vascularized tension-free anastomosis is of paramount importance for successful colorectal surgery and the hand-sewn or stapling technique is currently the most common surgical standard for restoration of bowel continuity. However, both techniques inevitably leave foreign materials within tissue, evoking an inflammatory reaction, thus potentially resulting in a number of anastomosis-related adverse effects. In particular, permanent presence of metallic foreign material after stapled anastomosis often contributes to the reduced size of the anastomotic lumen, and may be responsible for frequent postoperative stricture[1].

Anastomotic leakage still remains a serious problem associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. Although considerable variations are seen among surgeons, an overall clinically apparent anastomotic leakage proximal to the peritoneal reflection of the rectum ranges in frequency from 3.4% to 6%[2,3]. For anterior resection of the rectum, clinical leakage rate is known to be higher-between 2.9% and 15.3%[4-6]. In particular, not only increasing surgical morbidity and mortality, this complication may be associated with worse survival and higher recurrence after curative resection of colorectal cancer[7,8]. These drawbacks associated with conventional anastomotic techniques naturally lead surgeons to investigate a more ideal concept of the anastomosis. As an alternative to the end-to-end circular stapling device, a novel compression anastomosis ring (CAR™ 27; NiTi Surgical Solutions, Netanya, Israel) was introduced recently. It is made of shape-memory alloy of nickel-titanium (Nitinol), which is temperature dependent. Because this device is staple-free, there is no puncturing injury of the bowel wall, no risk of anastomotic bleeding, and it does not leave any permanent foreign material within the body. Within 6 to 11 d, the entire device together with the necrotized tissue detaches and is naturally eliminated from the body during bowel movements, leaving a wide and patent sutureless end-to-end anstomosis[9].

The aims of the current study were to present early clinical experience of the CAR™ 27 device in colorectal or colocolic end-to-end anastomosis after left-sided colon resection, and to evaluate the safety, efficacy, and technical feasibility of the device.

A non-randomized prospective data collection was performed for patients undergoing an elective left-sided colon resection, followed by an anastomosis using the CAR™ 27 for various left-colonic etiologies. Eligibility criteria of the use of the CAR™ 27 were anastomoses between the colon and at or above the intraperitoneal rectum. The surgical procedures were performed by a single surgeon (HJ Choi). Between November 2009 and January 2011, a total of 79 anastomoses were constructed by use of the CAR™ 27. Preoperatively, patients were informed of the method of bowel anastomosis. Data on patient demographics, surgical indications, operative procedure, perioperative course, and outcome were recorded prospectively on data sheets. The primary short-term clinical endpoint was the rate of anastomotic leakage, and other clinical outcomes, including intra- and postoperative complications, length of operation time and hospital stay, and the ring elimination time were recorded. No postoperative radiologic contrast study was performed routinely, and anastomotic leakage was diagnosed clinically.

Nitinol is a temperature-dependent shape memory alloy of nickel-titanium because it expands and flexes when cooled, but resumes its shape and size when it returns to its normal temperature[10]. Nitinol leaf springs are used in the CAR™ 27 to maintain a continuous pressure at the anastomosis independent of the thickness of tissue within the anastomosis. By cooling the ring in cold saline for about 30 s, the nitinol leaf springs flatten within the ring. When an anastomosis is created, the ring can accommodate to the different thicknesses of tissue within the anastomosis[11]. At body temperature, the nitinol leaf springs begin to return to their original shape, which closes the gap gradually until the trapped tissue becomes necrotic. As a result, healthy tissue connects the bowel ends at the ring’s outer perimeter to restore the bowel continuity.

The CAR™ 27 instrument consists of two main components, a main firing device and detachable compression elements (Figure 1). Compression elements are composed of a polyethylene anvil ring and a nitinol leaf spring-containing metal ring. Its use is similar to that of current curved circular staplers and it was manipulated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, the detachable anvil ring was inserted into the proximal bowel lumen and secured by a purse-string suture, when an anastomosis was ready after colon resection. After immersing the mounted ring with its loader in cold saline for several minutes, the ring was loaded to the distal end of the firing device. The firing device was then inserted transanally up to the stapled end of the colon or upper rectum. A thin trocar shaft emerged from the instrument to pierce the distal stapled end and was assembled to the shaft of the detachable anvil head by sliding one into the other. To deploy the CAR™ 27 from the housing onto the tissue, the operating knob was rotated until it could not be turned any further and the indicator line was visible, and the cutting trigger and the cutting handle were squeezed simultaneously. When fired, the device holds the two ends of tissue together with circumferentially placed barbed points, which penetrate through the tissue, holding it to the polyethylene anvil ring. After firing, the cutting trigger and the cutting handle were released and the instrument was withdrawn by pulling gently out of the rectum and anus. Because this device is temperature-dependent, warm saline was instilled around the anastomosis immediately after firing for quicker and securer return to its pre-deformed shape. Completeness of the anastomosis was confirmed by an air-leak test.

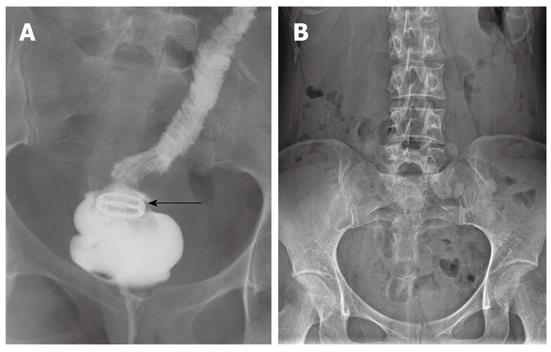

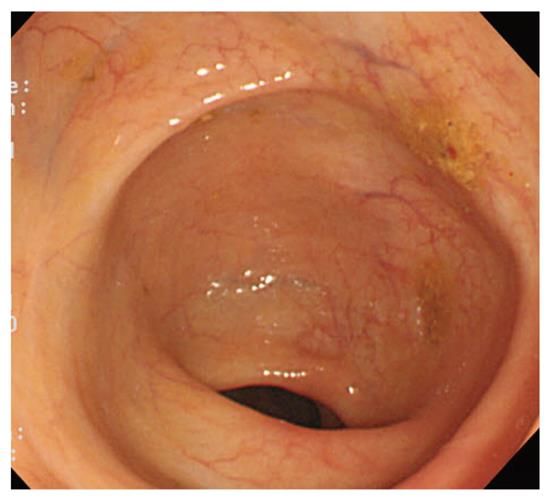

A total of 79 patients (male, 43) underwent an elective left-sided colon resection, followed by an anastomosis using the CAR™ 27. Patient demographics and primary diagnoses for a colectomy are shown in Table 1. Patients ranged in age from 30 to 82 (median, 64). The majority of patients (95%) received left-sided colon surgery for neoplastic etiologies. Surgical and pathologic data are shown in Table 2. Laparoscopic colectomy was performed in 70 patients, in whom two patients who underwent a laparoscopic anterior resection for sigmoid colon cancer were converted to open procedure (2.9%); one for bulky tumor with uterine adhesions and the other for physiologic adhesions with marginal artery injury. Combined procedures were performed in 5 patients [2, total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; 1, video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) wedge pneumonectomy; 1, cholecystectomy; 1, TAH]. Table 3 shows intra- and postoperative complications. There was no surgical mortality. There was an intraoperative complication associated with immature manipulation of the CAR™ 27 anastomosis. This 67-year old male received a laparoscopic anterior resection for sigmoid colon cancer. Immediately after deployment of the CAR™ 27 by firing, the proximal segment of the anastomosis was pulled upward to check perfectness of the anastomosis and the proximal side of the anastomosis was stripped off circumferentially. To solve this intraoperative problem, the device was dismantled and another new CAR™ 27 anastomosis was constructed. Premature enforced tension over the anastomosis with the CAR™ 27 still in the cold temperature might be a factor. One patient with sigmoid colon cancer showed anastomotic leakage after 6 d postoperatively. This 33-year-old female received a second laparoscopic exploration, and primary suture closure of the anastomotic defect (with the CAR™ 27 left) and temporary diverting ileostomy were performed. Postoperatively, all patients were informed that the ring would be expelled with bowel movement within 14 d after surgery. Practically, the exact date of expulsion of the ring could not be recorded because most patients were not aware that the ring had been expelled with stool. In the patient who received a diverting ileostomy for anastomotic leakage, the ring was not expelled and retained within the colon until 9 d after an ileostomy closure (Figure 2). Postoperatively, no patient manifested clinical symptoms suggestive of anastomotic stricture. Colonoscopy at 6-month follow-up showed a wide and patent anastomosis constructed by the CAR™ 27 (Figure 3).

| Compression anastomosis ring (n = 79) | |

| Gender | |

| Male | 43 |

| Female | 36 |

| Median age (yr, range) | 64 (30-82) |

| Primary diagnosis | |

| Neoplasm | |

| Sigmoid colon | 54 |

| Rectosigmoid junction | 17 |

| Descending colon | 4 |

| Carcinomatosis (cervical cancer) | 1 |

| Rectal prolapse | 1 |

| Sigmoid colonic ulcer | 1 |

| Sigmoid volvulus | 1 |

| CAR (n = 79) | |

| Median operation time (min, range) | 172.5 (110-430) |

| Median postoperative hospital stay (d, range) | 7 (4-29) |

| Type of surgery (laparoscopic/open) | |

| Anterior resection | 65(2)1/8 |

| Left hemicolectomy | 4/1 |

| Resection rectopexy | 1/0 |

| Combined procedure | |

| TAH + BSO | 2 |

| VATS pneumonectomy | 1 |

| Cholecystectomy | 1 |

| Total hysterectomy | 1 |

| Postoperative pathology for neoplasm | |

| Adenoma | 2 |

| Stage 0 | 2 |

| Stage I | 21 |

| Stage II A | 30 |

| Stage III A | 2 |

| Stage III B | 15 |

| Stage III C | 1 |

| Stage IV A | 2 |

| Metastatic adenosquamous carcinoma | 1 |

| CAR (n = 79) | |

| Premature enforced anastomotic disruption | 1 |

| Anastomotic leak | 1 |

As a secure anastomosis is the crucial step for successful colorectal surgery, search for the ideal concept of the anastomosis has been the subject of surgical interest since the 19th century. The goal has been to devise an innovative method to eliminate the risk of anastomosis-associated leakage. The concept of compression anastomosis is that two bowel ends are compressed together by a sutureless device, preventing leakage and facilitating the natural healing process in the compressed region. The idea of compression anastomosis was first devised by Denan who developed two metal rings kept in position by a spring in a canine model in 1826. In 1892, Murphy[12] introduced “Murphy’s button,” which consisted of a pair of metal rings that compressed circular segments of intestine, leading to tissue necrosis. But it was not popular in clinical use because of too tight compression that led to peripheral ischemia and premature necrosis. It took another 100 years for a new compression anastomosis device to be put into wide use. In 1985, Hardy et al[13] developed a biofragmentable anastomosis ring (ValtracTM BAR; Covidien, Mansfield, MA, United States) which is made of absorbable polyglycolic acid and radiopaque barium sulfate. To prevent tissue ischemia and to accommodate tissue thickness, margins of two identical rings are scalloped in shape and three gap-widths in the closed position (1.5, 2.0 and 2.5 mm) are available. A number of studies, including prospective randomized trials confirmed that the ValtracTM BAR was a safe and reliable compression anastomotic device in both elective and emergency surgery[14-17]; however, intraoperative problems have been reported, including failure of purse-string sutures, inappropriate selection of the size of the ValtracTM BAR with partial or full-thickness tear of the bowel wall, and failure of snap or shattering of the device[16,17].

Stepping forward, a novel compression anastomotic device made of nitinol (Nickel Titanium Naval Ordinance Laboratory), a shape memory alloy of nickel-titanium was introduced recently. Nitinol has two physical properties: temperature-dependent shape memory and super-elasticity. When cooled down, it has lower mechanical properties and becomes pliable, and then it becomes stable and returns to its pre-deformed shape at room temperature[10]. Super-elastic leaf springs made of nickel-titanium alloy are used in the NiTi CAR™ 27 in order to maintain a continuous pressure at the anastomosis independent of the thickness of tissue within the anastomosis[11]. The reparative healing process outside the ring produces an intact anastomosis before detachment and expulsion of the ring, leaving no foreign material within the body. The safety of this device has been demonstrated in animal studies[9,18]. Compared to other compression devices clinically, distinctive theoretical merits of the Nitinol are that it can accommodate different thickness around the circumference of the anastomosis and that it provides a constant, continuous, and uniform pressure over the pressed tissue along its compressing perimeter[19]. The CAR™ 27 was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the use in intestinal anastomoses in August, 2006 and by the Korea FDA in May, 2009.

Clinical experiences with use of the CAR™ 27 in colonic anastomoses are still very scarce. Preliminary results of a phase II, prospective, clinical trial by D’Hoore et al[20] were promising. In 10 patients who underwent high anterior resection or left colectomy, no anastomotic leakage occurred, and only three patients noticed passage of the ring through the anal canal. A recent prospective multicenter study comparing CAR™ 27 anastomosis (10 patients) with stapled anastomosis (13 patients) also demonstrated that the safety and efficacy of colorectal anastomosis using the CAR™ 27 in human was comparable to standard stapled anastomosis[19]. This study was first human multicenter trial but the sample size was too small to draw definite conclusions. The most recent non-randomized, prospective pilot study of the CAR™ 27 device in 23 patients undergoing a left-sided colectomy experienced an anastomotic leakage in one patient (4.3%) and stricture in two (8.6%)[21]. The current study has the largest sample size ever presented, demonstrating clinical safety relevant to CAR™ 27 anastomosis in both laparoscopic and open left-sided colectomies. A systemic review (Cochrane Database) of nine studies involving 1233 patients (622 stapled and 611 hand-sewn) found that overall rate of clinical leaks was 6.3% and 7.1%, respectively[22]. ValtracTM BAR instead of staples is a standard method of intraperitoneal colonic anastomosis in open surgery in our practice to minimize anastomotic stricture. The overall rate of anastomotic leak after the ValtracTM BAR colonic anastomosis in our series (632 patients) was 0.6%[23]. Compared to these results, leakage in one patient (1.3%) in this study implies that CAR™ 27 anastomosis is as safe and efficacious as conventional hand-sewn or stapling anastomosis. In addition, it is financially superior to end-to-end (EEA) stapling device (around $324 vs $360).

Issues associated with the CAR™ 27 anastomosis may deserve mentioning. Our experience of an intraoperative total anastomotic disruption associated with premature enforced tension over the anastomosis might reflect learning-curve error. Since this experience, it is our technical policy to leave the CAR™ 27 anastomosis soaked in warm saline for a few minutes, allowing the ring to recover to body temperature. Tulchinsky et al[19] recommended digital removal of the ring when it is not expelled spontaneously in a diverted patient. This seems to be an unnecessary maneuver. Moreover, in higher anastomosis from the anus, manual removal is not possible and forced instrumental removal of the retained ring may be rather harmful. Although the ring was not expelled and retained during the diversion in the leaked patient in this study, there were no problems associated with the retained ring during the diversion (134 d), and it expelled spontaneously after the ileostomy closure. In this sense, no specific maneuver is necessary and restoration of fecal stream after takedown of the diversion would be enough to eliminate the ring exteriorly.

To date, the clinical indication for the CAR™ 27 anastomosis is restricted to high level anastomoses at or above the anterior resection and it is not indicated in low rectal or anal anastomoses. Considering its superior technologic properties, anastomosis using the CAR™ 27 appears to be able to be performed safely in low anterior resection of the rectum. In addition, further prospective large-scale studies might be imperative to determine if the CAR™ 27 anasomosis can be constructed safely in diseased bowel such as Crohn’s colitis, and if it can be performed liberally in emergency surgery.

In conclusion, short-term evaluation of the CAR™ 27 anastomosis in patients undergoing laparoscopic or open elective left colectomy proved to be a safe and efficacious alternative to the standard hand-sewn or stapling technique. Along with its technical superiorities, a prospective large-scale clinical trial would confirm the validity of the CAR™ 27 in diverse clinical settings.

The authors would like to express their deepest thanks to NiTi Surgical Solutions for providing permission to reprint a picture of the NiTi CAR™ 27 instrument. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

A secure anastomosis is a crucial step for successful colorectal surgery and the hand-sewn or stapling technique is currently the most common surgical standard method of anastomosis. However, both techniques inevitably leave foreign materials within tissue, evoking an inflammatory reaction, thus potentially resulting in a number of anastomosis-related adverse effects.

To overcome safety limits in hand-sewn and stapled techniques, the concept of compression anastomosis is introduced. A novel compression anastomotic device (CAR™ 27), made of a shape memory alloy of nickel-titanium, has two peculiar physical properties: temperature-dependent shape memory and super-elasticity.

This is the largest study to evaluate the safety, efficacy, and technical feasibility of the CAR™ 27 anastomosis in left-sided colon resection. Short-term evaluation of the CAR™ 27 anastomosis in elective left colectomy is a safe and efficacious alternative to the standard hand-sewn or stapling technique. Among 79 patients, only one (1.3%) was complicated by anastomotic leakage in one patient, and it is financially superior to stapling device.

The study results suggest that the CAR™ 27 anastomosis can be applied both in laparoscopic and open left colectomy with safety. Despite encouraging results, clinical indication of the CAR™ 27 is, to date, limited to intraperitoneal anastomosis, and it is not indicated in low rectal or anal anastomoses. Considering its superior technologic properties, one of promising indications would be its use after a low anterior resection of the rectum. In addition, the potential expansion of its indications to patients with inflammatory bowel disease or with impaired healing for reasons such as radiation awaits further prospective clinical evaluations.

Temperature-dependent shape memory of the device is the property that it has lower mechanical properties and becomes supple when cooled down, and then it becomes stable and returns to its pre-deformed shape at room temperature.

This is a well written paper on the use of the compression anastomosis ring in left-sided colonic anastomosis and the results are comparable to stapled anastomosis.

| 1. | MacRae HM, McLeod RS. Handsewn vs. stapled anastomoses in colon and rectal surgery: a meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:180-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Golub R, Golub RW, Cantu R, Stein HD. A multivariate analysis of factors contributing to leakage of intestinal anastomoses. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;184:364-372. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Alves A, Panis Y, Trancart D, Regimbeau JM, Pocard M, Valleur P. Factors associated with clinically significant anastomotic leakage after large bowel resection: multivariate analysis of 707 patients. World J Surg. 2002;26:499-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 344] [Cited by in RCA: 341] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Vignali A, Fazio VW, Lavery IC, Milsom JW, Church JM, Hull TL, Strong SA, Oakley JR. Factors associated with the occurrence of leaks in stapled rectal anastomoses: a review of 1,014 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:105-113. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Karanjia ND, Corder AP, Bearn P, Heald RJ. Leakage from stapled low anastomosis after total mesorectal excision for carcinoma of the rectum. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1224-1226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 420] [Cited by in RCA: 401] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Antonsen HK, Kronborg O. Early complications after low anterior resection for rectal cancer using the EEA stapling device. A prospective trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 1987;30:579-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Law WL, Choi HK, Lee YM, Ho JW, Seto CL. Anastomotic leakage is associated with poor long-term outcome in patients after curative colorectal resection for malignancy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:8-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | McArdle CS, McMillan DC, Hole DJ. Impact of anastomotic leakage on long-term survival of patients undergoing curative resection for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1150-1154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 334] [Cited by in RCA: 357] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kopelman D, Lelcuk S, Sayfan J, Matter I, Willenz EP, Zaidenstein L, Hatoum OA, Kimmel B, Szold A. End-to-end compression anastomosis of the rectum: a pig model. World J Surg. 2007;31:532-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Szold A. New concepts for a compression anastomosis: superelastic clips and rings. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2008;17:168-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dauser B, Herbst F. NITI endoluminal compression anastomosis ring (NITI CAR 27®): A breakthrough in compression anastomoses? Eur Surg. 2009;41:116-119. |

| 12. | Murphy JB. Cholecysto-intestinal, gastro-intestinal, entero-intestinal anastomosis, and approximation without sutures. Med Rec NY. 1892;42:665-676. |

| 13. | Hardy TG Jr, Pace WG, Maney JW, Katz AR, Kaganov AL. A biofragmentable ring for sutureless bowel anastomosis. An experimental study. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28:484-490. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Corman ML, Prager ED, Hardy TG Jr, Bubrick MP. Comparison of the Valtrac biofragmentable anastomosis ring with conventional suture and stapled anastomosis in colon surgery. Results of a prospective, randomized clinical trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:183-187. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bubrick MP, Corman ML, Cahill CJ, Hardy TG Jr, Nance FC, Shatney CH. Prospective, randomized trial of the biofragmentable anastomosis ring. The BAR Investigational Group. Am J Surg. 1991;161:136-142. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Thiede A, Geiger D, Dietz UA, Debus ES, Engemann R, Lexer GC, Lünstedt B, Mokros W. Overview on compression anastomoses: biofragmentable anastomosis ring multicenter prospective trial of 1666 anastomoses. World J Surg. 1998;22:78-86; discussion 87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Choi HJ, Kim HH, Jung GJ, Kim SS. Intestinal anastomosis by use of the biofragmentable anastomotic ring: is it safe and efficacious in emergency operations as well? Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:1281-1286. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Stewart D, Hunt S, Pierce R, Dongli Mao M, Cook K, Starcher B, Fleshman J. Validation of the NITI Endoluminal Compression Anastomosis Ring (EndoCAR) device and comparison to the traditional circular stapled colorectal anastomosis in a porcine model. Surg Innov. 2007;14:252-260. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Tulchinsky H, Kashtan H, Rabau M, Wasserberg N. Evaluation of the NiTi Shape Memory BioDynamix ColonRing™ in colorectal anastomosis: first in human multi-center study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25:1453-1458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | D'Hoore A, Hompes D, Folkesson J, Penninckx F, PAhlman L. Circular 'superelastic' compression anastomosis: from the animal lab to clinical practice. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2008;17:172-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Buchberg BS, Masoomi H, Bergman H, Mills SD, Stamos MJ. The use of a compression device as an alternative to hand-sewn and stapled colorectal anastomoses: is three a crowd? J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:304-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lustosa SA, Matos D, Atallah AN, Castro AA. Stapled versus handsewn methods for colorectal anastomosis surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;CD003144. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Kim SH, Choi HJ, Park KJ, Kim JM, Kim KH, Kim MC, Kim YH, Cho SH, Jung GJ. Sutureless intestinal anastomosis with the biofragmentable anastomosis ring: experience of 632 anastomoses in a single institute. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:2127-2132. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Peer reviewers: Aravind Suppiah, Dr., PhD, 5 Gillyon Close, Beverley, East Yorkshire, HU17 0TW, United Kingdom; Venkatesh Shanmugam, MBBS, MS, Dip NB, FRCS, MD, Specialist Registrar (Trent Deanery), Royal Derby Hospital, Uttoxeter Road, Derby, DE22 3NE, United Kingdom; Wai Lun Law, FACS, Clinical Professor, Chief, Division of Colorectal Surgery, Department of Surgery, Queen Mary Hospital, The University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong, China; Paulino Martínez Hernández Magro, Dr., Department of Colon and Rectal Surgery, Hospital San José de Celaya, Eje Vial Norponiente No 200-509, Colonia Villas de la Hacienda, 38010 Celaya, México

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Zhang DN