Published online Sep 28, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i36.4118

Revised: March 24, 2011

Accepted: March 31, 2011

Published online: September 28, 2011

AIM: To investigate whether bile duct angulation and T-tube choledochostomy influence the recurrence of choledocholithiasis.

METHODS: We conducted a retrospective study inclu-ding 259 patients who underwent endoscopic sphincterotomy and cholecystectomy for choledocholithiasis between 2000 and 2007. The imaginary line was drawn along the center of the bile duct and each internal angle was measured at the two angulation sites of the bile duct respectively. The values of both angles were added together. We then tested our hypothesis by examining whether T-tube choledochostomy was performed and stone recurrence occurred by reviewing each subject’s medical records.

RESULTS: The overall recurrence rate was 9.3% (24 of 259 patients). The mean value of sums of angles in the recurrence group was 268.3°± 29.6°, while that in the non-recurrence group was 314.8°± 19.9° (P < 0.05). Recurrence rate of the T-tube group was 15.9% (17 of 107), while that of the non T-tube group was 4.6% (7 of 152) (P < 0.05). Mean value of sums of angles after T-tube drainage was 262.5°± 24.6° and that before T-tube drainage was 298.0°± 23.9° in 22 patients (P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION: The bile duct angulation and T-tube choledochostomy may be risk factors of recurrence of bile duct stones.

- Citation: Seo DB, Bang BW, Jeong S, Lee DH, Park SG, Jeon YS, Lee JI, Lee JW. Does the bile duct angulation affect recurrence of choledocholithiasis? World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(36): 4118-4123

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i36/4118.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i36.4118

Since its introduction in 1974, endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) has become a well established therapeutic method for the extraction of common bile duct (CBD) stones[1,2]. In previous studies of EST, 4%-24% of patients experienced recurrent CBD stones during follow-up intervals of up to 15 years[3-5]. The suggested causes of recurrent bile duct stones after EST are bile duct inflammation, papillary stenosis, dilated common bile duct, peripapillary diverticulum, reflux of the duodenal contents into the bile duct, and foreign bodies within the bile duct[6,7]. After EST, the biliary sphincter is rendered permanently insufficient[8]. The loss of this physiologic barrier between duodenum and biliary tract results in duodenocholedochal reflux and bacterial colonization of the biliary tract[9,10]. The presence of bacteria in the biliary system might lead to late complications after EST. These complications may include recurrence of CBD stones from deconjugation of bilirubin by bacterial enzymes[11], inflammatory changes of the biliary and/or hepatic system[12,13], recurrent ascending cholangitis[14], and even malignant degeneration[13,15].

Bile stasis may be one of the possible mechanisms of stone recurrence[16]. If bile flow can be decreased by the bile duct angulation, it may be a risk factor of stone recurrence. In a previous study, it was disclosed that in treatment of CBD stones, a T-tube drainage group had a higher recurrence rate of stones than either a choledochoduodenostomy group or an EST group, although their accurate mechanism was not elucidated[17]. It was also reported that the angulation of the extrahepatic bile duct-so called “the elbow sign”-occurred as a sequela of T-tube drainage[18]. Therefore, we investigated whether draining the T-tube changes configuration of the extrahepatic bile duct significantly and then whether bile duct deformity affects recurrence of CBD stones.

All patients who were treated for choledocholithiasis by means of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with EST between January 2000 and December 2007 in our institution were recruited. Their medical records were retrospectively reviewed. Among them, patients who met the following criteria were selected: (1) complete clearance of the bile duct stones was achieved; (2) cholecystectomy performed; (3) absence of bile duct stricture; (4) absence of concurrent hepatolithiasis; (5) absence of coexisting malignant neoplasm; and (6) absence of coexisting severe medical disease. Consequently, in total 259 patients were enrolled in the study.

For all the patients, the following data were collected: gender, age, recurrence, presence of periampullary diverticulum, maximal CBD diameter and presence of T-tube drainage. We divided them into two groups; recurrent and non-recurrent groups, and the sum of extrahepatic bile duct angles and maximal CBD diameter between both groups was compared. EST was performed completely by traction-type or needle-knife sphincterotome and the bile duct stones were extracted with basket and/or stone-retrieval balloon catheters. After extraction of CBD stones, we performed a regular check-up on each patient at the outpatient department base, and considered absence of symptoms of biliary colic or cholangitis episode as absence of recurrence by using telephone interviews in patients who were missed.

Periampullary diverticulum was defined as the presence of a diverticulum within a 2-cm radius from ampulla of Vater. We could identify whether periampullary diverticulum was present or not in 231 of the subjects. The information was missing from the medical records of the remaining patients. We divided patients into two groups: non-periampullary diverticulum and periampullary diverticulum groups, and the recurrence rate between the two groups was compared.

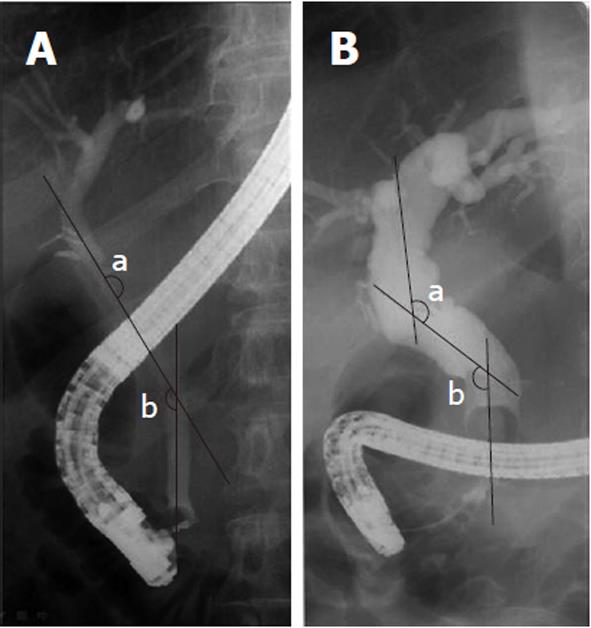

There were films of acceptable quality, taken in the prone position during ERCP. When the exrahepatic bile duct was deformed, the number of its angulation site was one or two in most patients. The angles were measured at the intersection of imaginary lines drawn down the center of the bile duct. Its intersection did not necessarily occur within the lumen of the duct, particularly where angulation took the form of a gentle curve. Each internal angle was measured at the two angulation sites of the proximal and distal bile duct level respectively by one experienced radiologist (Figure 1). The values of both angles were added together to estimate the grade of angulation. The smaller sum of angles implies more angulation.

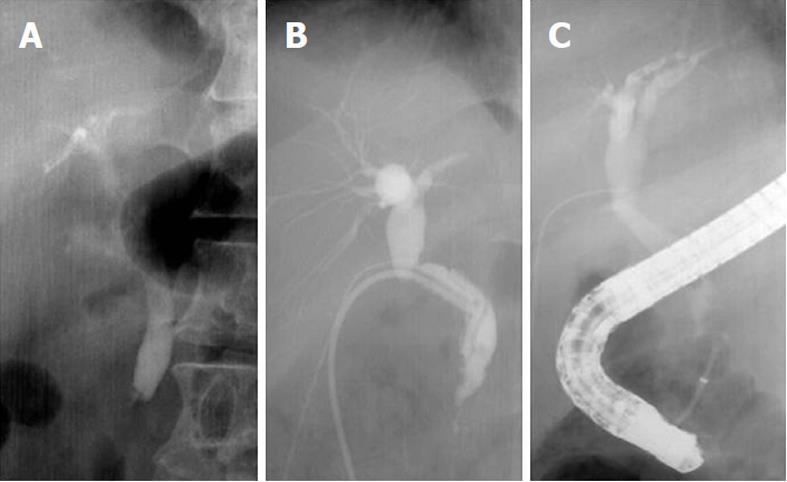

T-tube drainage was performed during the cholecystectomy when the bile duct was injured surgically or when a bile duct stone remained after EST. We divided patients into two groups; T-tube drainage (107 patients) and non-T-tube drainage group (152 patients). The recurrence rate in each group and the sum of angles, especially the sum of the angles before and after T-tube drainages in 22 patients whose films of ERCP before and after T-tube drainage were available among T-tube drainage group, were determined. We compared the recurrence rate and sum of angles between the T-tube drainage group and the non-T-tube drainage group, and evaluated the change of the sum of angles before and after the T-tube drainages in 22 patients to find the influence of T-tube drainage on bile duct configuration (Figure 2).

We defined transverse diameter of the CBD as a diameter measured in the line which forms a right angle to an imaginary line drawing down along the center of the CBD lumen. We measured the maximal transverse diameter of the CBD in all subjects and corrected for the magnification, with the external diameter of the distal end of the duodenoscope as a reference. We also evaluated the recurrence rate according to the CBD diameter.

Categorical variables (gender, presence of periampullary diverticulum and presence of T-tube drainage) were compared by chi-square test or Fisher exact test. Continuous variables (age, CBD diameter, sum of angle) were analyzed using the Student t test when the variables were normally distributed or by using the Mann Whitney U test for non-normal distribution. Significant predictors for choledocholithiasis recurrence identified by univariate analyses were included in a multiple logistic regression model to determine the most significant risk factors for recurrence of the bile duct stones. For multivariate analysis, we categorized continuous variables into two subgroups: age (< 65 years vs≥ 65 years), sum of angle (< 270°vs≥ 270°), and maximal transverse CBD diameter (< 13 mm vs≥ 13 mm).

Statistical analysis were conducted using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) computer program (version 14.00).

Two hundred and fifty-nine patients were included in the study. Median age was 58 years (range, 17-85 years). There were 132 (50.9%) women and 127 (49.1%) men. Median follow-up period was 47.9 mo (6-101 mo). The results of univariate analyses for recurrence of bile duct stones in relation to each factor were presented in Table 1.

| Variable | Non recurrence group(n = 235) | Recurrence group(n = 24) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 57.5 ± 15.2 | 62.4 ± 11.6 | 0.064 | |

| Gender (M/F) | 116/119 | 11/13 | 0.742 | |

| Common bile duct diameter (mm)1 | 15.8 ± 6.2 | 20.6 ± 7.6 | 0.001 | |

| Sum of angle (°)1 | 314.9 ± 20.0 | 268.3 ± 29.6 | 0.001 | |

| T-tube drainage | No | 145 (95.4) | 7 (4.6) | 0.002 |

| Yes | 90 (84.1) | 17 (15.9) | ||

| Periampullary diverticulum2 | No | 111 (93.3) | 8 (6.7) | 0.091 |

| Yes | 97 (86.6) | 15 (13.4) |

The overall recurrence rate of CBD stones was 9.3% (24 of 259 patients). The recurrence rate was 8.7% (11 of 127 patients) in males and 9.9% (13 of 132 patients) in females respectively.

A total of 13.4% (15 of 112) of the patients with periampullary diverticulum developed recurrent stones, while 6.7% (8 of 119) of those without diverticulum showed recurrence. There was no evidence that the periampullary diverticulum exerted a significant influence on the recurrence of bile duct stones statistically (P = 0.091). Seventeen of 107 patients (15.9%) who underwent T-tube drainage had a recurrence, compared with 7 of 152 patients (4.6%) without T-tube drainage, and the presence of T-tube drainage was shown to be statistically associated with the recurrence of CBD stones (P = 0.002).

The mean value of the sum of angles in the non-recurrence group was 314.9°± 20.0°, while the mean sum of angles in the recurrence group was 268.3°± 29.6° (P = 0.001). These results mean that the more angulation in the extrahepatic bile duct could develop, the greater recurrence of the stone.

The mean maximal transverse CBD diameter in the non-recurrence group was 15.8 ± 6.2 mm while the mean value of CBD in the recurrence group was 20.6 ± 7.6 mm. CBD diameter was a significant risk factor for recurrence on univariate analysis (P = 0.001).

The mean value of sums of angles at the cholangiogram before T-tube choledochostomy was 311.7°± 22.4°

in T-tube group, while that in the non T-tube group was 314.9°± 19.3° (P = 0.232). On the other hand, the mean value of sums of angles before T-tube drainage was 298.0°± 3.9° , while after T-tube drainage, it was 262.5°± 24.6° in some patients (n = 22) who underwent ERCP after removal of the T-tube among members of the T-tube group (P = 0.001). Consequently, these results suggested that T-tube drainage may affect bile duct angulation.

A univariate analysis revealed that CBD diameter, T-tube drainage and sum of angle were significant risk factors for the recurrence of choledocholithiasis (P < 0.05). But multivariate analyses of all variables that reached a P value of less than 0.1 in univariate analysis were performed. On multivariate analysis, angulation was the only independent risk factor for the recurrence of choledocholithiasis (Table 2).

| Recurrence of bile duct stones | |||

| Variables | Odds ratio | P value | 95% CI1 |

| Periampullary diverticulum | 2.648 | 0.107 | 0.809-8.668 |

| Common bile duct diameter | 3.011 | 0.152 | 0.564-11.700 |

| T-tube drainage | 2.578 | 0.119 | 0.785-8.470 |

| Sum of angle (°) | 17.897 | 0.000 | 5.083-63.015 |

| Age ≥ 65 years | 0.372 | 0.102 | 0.113-1.219 |

ERCP with EST is the therapeutic procedure of choice for CBD stones. Early complications of EST include acute pancreatitis, bleeding, duodenal perforation, and acute cholangitis. On the other hand, its late complications include recurrence of stones and papillary stenosis[19,20]. In long-term follow-up studies after EST, the recurrence rate of CBD stones in patients with cholecystectomy has been in the range of 4% to 24%[3-5]. However, the theory that loss of sphincter function after EST leads to formation of recurrent CBD stones seems to need validation. Several authors have demonstrated that the biliary tree becomes infected with bacteria after EST[9,10] and there is substantial evidence that bacteria play an essential role in the formation of brown pigment stones. Some bacterial species, especially Escherichia coli[21], produce enzymes such as β-glucuronidase that are known to precipitate bilirubin and calcium[11], the main components of brown pigment stone[22]. Furthermore, electron microscopy studies have demonstrated that bacteria are present in the core of brown pigment stone whereas they are absent in cholesterol and black pigment stone[14,23,24].

Apart from bacterial infection, biliary stasis is thought to be an important factor in the pathogenesis of recurrent bile duct stones[6,16,25]. The markedly dilated bile duct is often contaminated with bacteria and also leads to bile stasis, which is thought to be an important factor in the pathogenesis of recurrent stones. The association between dilated CBD and stone recurrence has been reported in previous studies of post-EST patients[26,27]. In the univariate analysis of our study, in the recurrence group (n = 21, mean CBD diameter = 20.6 mm ± 7.6 mm) there was greater dilation in the extrahepatic bile duct than in the non-recurrence group (n = 200, mean CBD diameter = 15.8 mm ± 6.2 mm) (P = 0.001). Therefore dilated bile ducts may be another important risk factor of CBD stone recurrence by causing impaired bile flow.

Previous studies of the peripapillary diverticulum in relation to recurrence of bile duct stone have disclosed inconsistent results[28-31]. Biliary stasis in patients with diverticulum could be caused by either mechanical factors or the presence of coexisting motility disorders involving the sphincter of Oddi[28-31]. Theoretically, the effect of the diverticulum on bile flow might not completely disappear after the EST. In our study, the recurrence rate of the diverticulum group (n = 112, 13.4%) was higher than that of the non-diverticulum group (n = 119, 6.7%), but the result was not statistically significant (P = 0.91). Hence further studies on periampullary diverticulum as a risk factor of stone recurrence might be needed.

Bile duct angulation may cause stasis of bile flow. Warren suggested that angulation of CBD is associated with choledocholithiasis[32]. Mean cholangiographic angulation of CBD differed significantly between patients with cholelithiasis only and those with choledocholithiasis in this previous series. The degree of ductal angulation may be a useful consideration in development of bile duct stones. Recently two reports showed angulation of the CBD contributes to biliary stasis, and hence predisposes to recurrent choledocholithiasis[33,34]. In the current study, the recurrence group (n = 24, mean of sums of angles = 268.3°± 29.6°) was more angulated in the extrahepatic bile duct than the non-recurrence group (n = 235, mean of sum of angles = 314.9°± 20.0°) (P < 0.05). In multivariate analysis, the sum of angles was the only independent risk factor of CBD stone recurrence (Table 2).

There was a previous study describing long-term results of medical or surgical treatment in patients with choledocholithiasis[17]. Two hundred and thirteen patients were treated for CBD stones, and then the patients were divided into 3 groups based on the treatment modality: group 1, choledocholithotomy and T-tube choledochostomy; group 2, choledochoduodenostomy; and group 3, endoscopic sphincterotomy. Recurrence of choledocholithiasis was examined for each type of treatment modality. This study suggested that patients treated by T-tube drainage had more recurrent bile duct stones than those in the choledochoduodenostomy or EST groups, but accurate mechanisms were not clearly demonstrated.

Lee and Burhenne suggested that extrahepatic bile duct angulation was caused by T-tube drainage[18]. They observed lateral distortion in the shape of the bile ducts in a considerable number of patients with an indwelling T-tube such that an angle measured between the proximal and distal parts of the duct, centered at the site of T-tube drainage insertion, decreased to a range of 60 to 158. They have called this finding the “elbow sign”. In the current study, the mean sum of angles before T-tube drainage was 298.0°± 23.9°, while the mean value of angles after T-tube drainage was 262.5°± 24.6° in the same patients. The sum of the angles in the CBD changed after T-tube drainage by 35.5° and was statistically significant (P < 0.05). Furthermore, the extrahepatic bile duct deformity caused by T-tube drainage influenced the recurrence rate of CBD stones. The recurrence rate of the non-T-tube drainage group was 4.6%, while the recurrence rate of the T-tube drainage group was 15.9% (P < 0.05). It is presumed that T-tube placement could introduce local adhesion[33], which, in turn, influences the angulation of the bile duct and then leads to recurrence of bile duct stones as one of the mechanisms.

Our study has some limitations. First, this study is retrospective. Second, we did not prove recurrence with repeat ERCP or cholangiogram in every patient. It may have ascertainment bias. Third, we should estimate the three dimensional image, but we measure bile duct angulation by two-dimensional fluoroscopic imaging. This may show some difference from real angulation. Practically, it is difficult to get three dimensional bile duct images. Fourth, there may be several possible confounders which we did not consider. Medication such as ursodeoxycholic acid and the time of drainage of contrast from the bile duct were not reported in our series. On account of these limitations, it is difficult to be absolutely certain that our specific risk factors were solely responsible for the recurrence of choledocholithiasis.

In conclusion, subsequent to endoscopic biliary sph-incterotomy and clearance of bile duct stones, three significant risk factors for the recurrence of the stone were identified on univariate analyses, although bile duct angulation was the only risk factor for recurrence of choledocholithiasis in the multivariate analysis. Patients with a more angulated and dilated bile duct, and a history of T-tube choledochostomy developed stone recurrence more frequently. T-tube choledochostomy performed after cholecystectomy were prone to recurrence of stones by an influence on bile duct angulation.

After endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST), 4%-24% of patients might experience recurrent choledocholithiasis. The risk of stone recurrence is an important issue, especially for relatively young patients. Bile duct angulation may be a risk factor of stone recurrence by decreasing bile flow.

The risk factors for true recurrence of bile duct stones after EST are suboptimally defined. Until now, infection along the bile duct and bile stasis were thought to contribute to the recurrence.

Recent several studies showed the association between bile duct angulation and recurrence of stones. The authors added more information about that. In addition, the authors suggested that T-tube choledochostomy influences the recurrence of choledocholithiasis by angulating the bile duct.

This article provides important data about the risk factors of choledocholithiasis recurrence. By identifying risk factors for stone recurrence, people can improve outcomes by prophylactic treatments or earlier intervention.

This is an interesting study that investigated the risk factors of recurrence of common bile duct stones. This study suggested an association between T-tube drainage and recurrence of choledocholithiasis by analyzing the angulation of the common bile duct before and after T-tube drainage.

| 1. | Classen M, Demling L. [Endoscopic sphincterotomy of the papilla of vater and extraction of stones from the choledochal duct (author's transl)]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1974;99:496-497. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Kawai K, Akasaka Y, Murakami K, Tada M, Koli Y. Endoscopic sphincterotomy of the ampulla of Vater. Gastrointest Endosc. 1974;20:148-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 514] [Cited by in RCA: 460] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Seifert E. Long-term follow-up after endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST). Endoscopy. 1988;20 Suppl 1:232-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Hawes RH, Cotton PB, Vallon AG. Follow-up 6 to 11 years after duodenoscopic sphincterotomy for stones in patients with prior cholecystectomy. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:1008-1012. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Ikeda S, Tanaka M, Matsumoto S, Yoshimoto H, Itoh H. Endoscopic sphincterotomy: long-term results in 408 patients with complete follow-up. Endoscopy. 1988;20:13-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Geenen JE, Toouli J, Hogan WJ, Dodds WJ, Stewart ET, Mavrelis P, Riedel D, Venu R. Endoscopic sphincterotomy: follow-up evaluation of effects on the sphincter of Oddi. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:754-758. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Cheon YK, Lehman GA. Identification of risk factors for stone recurrence after endoscopic treatment of bile duct stones. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:461-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Thistle JL. Pathophysiology of bile duct stones. World J Surg. 1998;22:1114-1118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gregg JA, De Girolami P, Carr-Locke DL. Effects of sphincteroplasty and endoscopic sphincterotomy on the bacteriologic characteristics of the common bile duct. Am J Surg. 1985;149:668-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sand J, Airo I, Hiltunen KM, Mattila J, Nordback I. Changes in biliary bacteria after endoscopic cholangiography and sphincterotomy. Am Surg. 1992;58:324-328. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Nakai K, Tazuma S, Nishioka T, Chayama K. Inhibition of cholesterol crystallization under bilirubin deconjugation: partial characterization of mechanisms whereby infected bile accelerates pigment stone formation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1632:48-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Greenfield C, Cleland P, Dick R, Masters S, Summerfield JA, Sherlock S. Biliary sequelae of endoscopic sphincterotomy. Postgrad Med J. 1985;61:213-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kurumado K, Nagai T, Kondo Y, Abe H. Long-term observations on morphological changes of choledochal epithelium after choledochoenterostomy in rats. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:809-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Goldman LD, Steer ML, Silen W. Recurrent cholangitis after biliary surgery. Am J Surg. 1983;145:450-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kinami Y, Ashida Y, Seto K, Takashima S, Kita I. Influence of incomplete bile duct obstruction on the occurrence of cholangiocarcinoma induced by diisopropanolnitrosamine in hamsters. Oncology. 1990;47:170-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lai KH, Peng NJ, Lo GH, Cheng JS, Huang RL, Lin CK, Huang JS, Chiang HT, Ger LP. Prediction of recurrent choledocholithiasis by quantitative cholescintigraphy in patients after endoscopic sphincterotomy. Gut. 1997;41:399-403. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Uchiyama K, Onishi H, Tani M, Kinoshita H, Kawai M, Ueno M, Yamaue H. Long-term prognosis after treatment of patients with choledocholithiasis. Ann Surg. 2003;238:97-102. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Lee SH, Burhenne HJ. Extrahepatic bile duct angulation by T-tube: the elbow sign. Gastrointest Radiol. 1991;16:157-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Prat F, Malak NA, Pelletier G, Buffet C, Fritsch J, Choury AD, Altman C, Liguory C, Etienne JP. Biliary symptoms and complications more than 8 years after endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledocholithiasis. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:894-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in RCA: 1703] [Article Influence: 56.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 21. | Leung JW, Sung JY, Costerton JW. Bacteriological and electron microscopy examination of brown pigment stones. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:915-921. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Cetta F. The role of bacteria in pigment gallstone disease. Ann Surg. 1991;213:315-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kaufman HS, Magnuson TH, Lillemoe KD, Frasca P, Pitt HA. The role of bacteria in gallbladder and common duct stone formation. Ann Surg. 1989;209:584-591; discussion 591-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Smith AL, Stewart L, Fine R, Pellegrini CA, Way LW. Gallstone disease. The clinical manifestations of infectious stones. Arch Surg. 1989;124:629-633. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Cetta F. The possible role of sphincteroplasty and surgical sphincterotomy in the pathogenesis of recurrent common duct brown stones. HPB Surg. 1991;4:261-270. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Kim DI, Kim MH, Lee SK, Seo DW, Choi WB, Lee SS, Park HJ, Joo YH, Yoo KS, Kim HJ. Risk factors for recurrence of primary bile duct stones after endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:42-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ueno N, Ozawa Y, Aizawa T. Prognostic factors for recurrence of bile duct stones after endoscopic treatment by sphincter dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:336-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kim MH, Myung SJ, Seo DW, Lee SK, Kim YS, Lee MH, Yoo BM, Min MI. Association of periampullary diverticula with primary choledocholithiasis but not with secondary choledocholithiasis. Endoscopy. 1998;30:601-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Chandy G, Hart WJ, Roberts-Thomson IC. An analysis of the relationship between bile duct stones and periampullary duodenal diverticula. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;12:29-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Hall RI, Ingoldby CJ, Denyer ME. Periampullary diverticula predispose to primary rather than secondary stones in the common bile duct. Endoscopy. 1990;22:127-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kennedy RH, Thompson MH. Are duodenal diverticula associated with choledocholithiasis? Gut. 1988;29:1003-1006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Warren BL. Association between cholangiographic angulation of the common bile duct and choledocholithiasis. S Afr J Surg. 1987;25:13-15. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Keizman D, Shalom MI, Konikoff FM. An angulated common bile duct predisposes to recurrent symptomatic bile duct stones after endoscopic stone extraction. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:1594-1599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Keizman D, Ish Shalom M, Konikoff FM. Recurrent symptomatic common bile duct stones after endoscopic stone extraction in elderly patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:60-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Peer reviewers: Giuseppe Currò, MD, University of Messina, Via Panoramica, 30/A, 98168 Messina, Italy; Beata Jolanta Jablońska, MD, PhD, Department of Digestive Tract Surgery, University Hospital of Medical University of Silesia, Medyków 14 St. 40-752 Katowice, Poland

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Zhang DN