Published online Sep 28, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i36.4109

Revised: February 28, 2011

Accepted: March 7, 2011

Published online: September 28, 2011

AIM: To compare the effectiveness of argon plasma coagulation (APC) and heater probe coagulation (HPC) in non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

METHODS: Eighty-five (18 female, 67 male) patients admitted for acute gastrointestinal bleeding due to gastric or duodenal ulcer were included in the study. Upper endoscopy was performed and HPC or APC were chosen randomly to stop the bleeding. Initial hemostasis and rebleeding rates were primary and secondary end-points of the study.

RESULTS: Initial hemostasis was achieved in 97.7% (42/43) and 81% (36/42) of the APC and HPC groups, respectively (P < 0.05). Rebleeding rates were 2.4% (1/42) and 8.3% (3/36) in the APC and HPC groups, respectively, at 4 wk (P > 0.05).

CONCLUSION: APC is an effective hemostatic method in bleeding peptic ulcers. Larger multicenter trials are necessary to confirm these results.

- Citation: Karaman A, Baskol M, Gursoy S, Torun E, Yurci A, Ozel BD, Guven K, Ozbakir O, Yucesoy M. Epinephrine plus argon plasma or heater probe coagulation in ulcer bleeding. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(36): 4109-4112

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i36/4109.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i36.4109

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is a common and life-threatening medical emergency. UGIB is defined as bleeding proximal to the ligament of Treitz. At least 80% of patients admitted to hospital because of acute bleeding have an excellent prognosis; generally, bleeding stops spontaneously and circulatory supportive therapy is adequate. Endoscopic therapy has been shown to reduce the rate of rebleeding, blood transfusion and surgery[1]. Endoscopic therapy is indicated in the following situations: (1) bleeding esophageal varices; (2) peptic ulcer with major stigmata of recent hemorrhage (active spurting bleeding, non-bleeding visible vessel or non-adherent blood clot); (3) vascular malformations including actively bleeding arteriovenous malformation, gastric antral vascular ectasia, and Dieulafoy malformation; and (4) active bleeding from a Mallory-Weiss tear.

Endoscopic hemostasis has significantly improved the outcome of patients with gastrointestinal bleeding. Contact thermal coagulation with heater probe and argon plasma coagulation (APC) are among the hemostatic methods for bleeding peptic ulcers. Devices are applied directly to the bleeding point to cause coagulation and thrombosis in heater probe coagulation (HPC). The heater probe is pushed firmly on to the bleeding lesion to apply tamponade and deliver defined pulses of heat energy. APC is a non-contact method of delivering high-frequency monopolar current through ionized and electrically conductive argon gas[2].

The aim of this study was to compare these two methods for UGIB due to gastric and duodenal ulcers. The primary outcome measure was initial hemostasis and secondary outcome measure was recurrence of bleeding. This study was approved by Erciyes University Ethical Committee.

All patients admitted for acute gastrointestinal bleeding due to gastric and duodenal ulcers were included in the study. Gastrointestinal bleeding was diagnosed only if medical staff witnessed hematemesis or melena, or detected black, tarry material on digital examination of the rectum. Patients with actively bleeding peptic ulcers, ulcers with adherent clots, or ulcers with non-bleeding visible vessels were randomly assigned to epinephrine injection plus HPC or epinephrine injection plus APC. Informed consent was obtained before the procedure and this was solely for the procedure itself. Patients with previous malignant ulcers, and unidentifiable ulcers because of torrential bleeding were excluded.

Randomization of patients was carried out by means of sealed numbered envelopes. Informed consent was obtained for therapeutic endoscopic intervention. Patients were blind to the study. All patients underwent endoscopy within 24 h of admission. All procedures were performed by experienced gastroenterologists (experienced endoscopist as a specialist in gastroenterology with a minimum of 3 years of post-training experience) with a Fujinon-2200 endoscope. An Olympus HPU-20 heater probe system with 10 F probes was used with power settings of 30-40 J. The heater probe was pushed firmly on to the bleeding lesion to apply compression and to cause coagulation and thrombosis. We used an Erbe 200 D APC unit, which consists of an argon gas source, a high-frequency electrosurgical unit, an APC probe, and foot switches to activate the argon gas source and current generator. Operative distance between the probe and tissue was adjusted to 2-10 mm by sense of proportion (Technically, APC cannot be activated unless the tip of the probe is at least 2-10 mm distant from the ulcer region. An automated switch-off system has been integrated into the system to avoid damage to the endoscope when this distance increases). Power/gas flow settings were 50 W and 2 L/min. All endoscopists used the same settings on the instrument. Epinephrine injection (5-6 mL, 1/10 000 dilution) was applied around the ulcer in all patients, before both of these two methods.

Initial hemostasis was defined as cessation of active bleeding. All the patients were treated with the same protocol after the endoscopic procedure. A policy of early feeding was adopted, and intravenous omeprazole was prescribed at a dose of 40 mg/d. Primary failure was defined as failure to stop bleeding during initial endoscopy. Recurrent bleeding was defined by one of the following: 2 g/dL drop in hemoglobin value compared to that when the patient was discharged from hospital; fresh hematemesis; hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg) with tachycardia (pulse > 110 beats/min); or melena after endoscopic treatment. Patients who did not have initial hemostasis were excluded during evaluation of rebleeding rates. Patients were followed for the next 4 wk after initial hemostasis to monitor rebleeding. Distribution of bleeding focus and severity of bleeding (by using Forrest Classification) was found to be similar by χ2 analysis (Table 1).

| APC | HPC | Total | P value | |

| Male | 33 | 34 | 67 | 0.418 |

| Female | 10 | 8 | 18 | 0.418 |

| Duodenal ulcer | 23 | 25 | 48 | 0.366 |

| Gastric ulcer | 20 | 17 | 37 | 0.366 |

| Age (yr) | 57 | 52 | 54 | 0.19 |

| Forrest | ||||

| 1a | 4 | 9 | 13 | |

| 1b | 39 | 33 | 72 | 0.291 |

Analysis of data was performed using SPSS version 16.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States). P < 0.05 was regarded as significant. We calculated the power of the study with PASS 2008 software, with α = 0.05, n = 85, degrees of freedom = 1, and power of study = 99.9%.

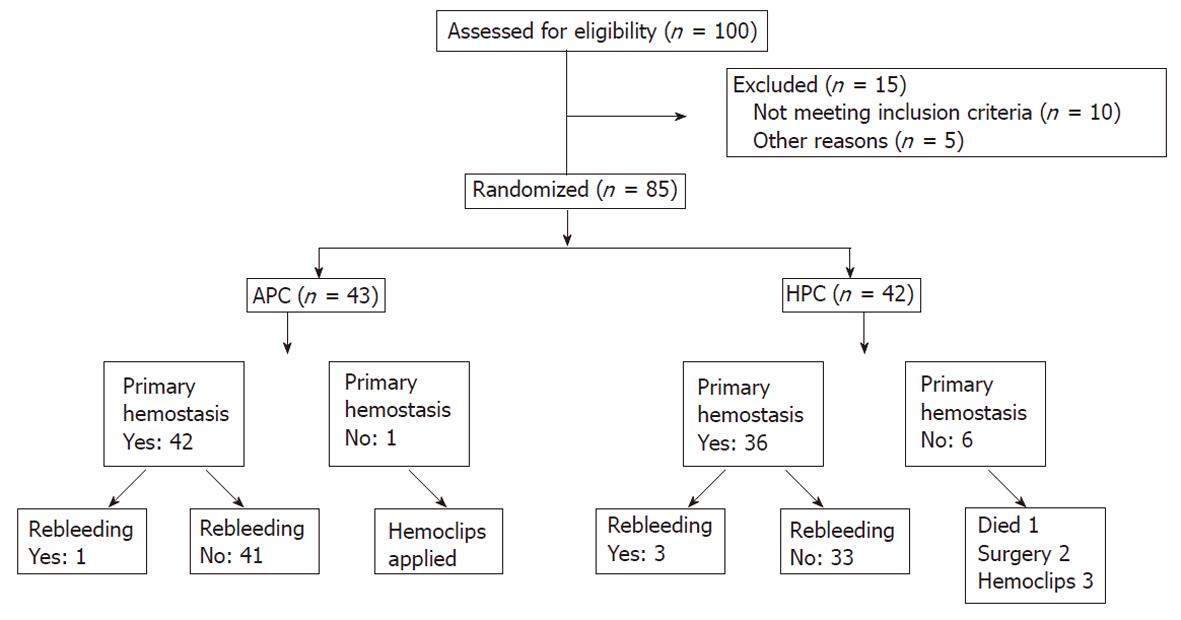

Eighty-five (18 female, 67 male) patients were included in the study between February 2008 and November 2009 in the Gastroenterology Department, Erciyes University School of Medicine. Forty-two patients received HPC and 43 received APC. Forty-eight bleeding duodenal ulcers (25 received HPC therapy and 23 APC) and 37 bleeding gastric ulcers (17 received HPC therapy and 20 APC) were included. A consort flow diagram was designed and is presented in Figure 1.

Initial hemostasis was achieved in 97.7% (42/43) and 81% (36/42) of the APC and HPC groups, respectively (P < 0.05). There were significant differences in initial hemostasis rates (P = 0.015). One patient died, two had surgery, and three had hemoclips applied in the HPC group; one patient had hemoclips applied in the APC group, who did not have initial hemostasis. Rebleeding rates were 2.4% (1/42) and 8.3% (3/36) in the APC and HPC groups, respectively at 4 wk after index bleeding (P = 0.25). Although rebleeding rate was greater in the HPC group, there was no significant difference between the groups (Table 2).

| No. of cases(gastric/duodenal ulcer) | Initial hemostasis(%) | Rebleeding(%) | |

| APC | 43 (20-23) | 42/43 (97.7%) | 1/42 (2.4%) |

| HPC | 42 (17-25) | 36/42 (81%) | 3/36 (8.3%) |

| Total | 85 (37-48) | 78 (91.7%) | 4/78 (5.1%) |

Acute UGIB is a common medical emergency that carries hospital mortality in excess of 10%[3]. Bleeding stops spontaneously in about 80% of patients with non-variceal UGIB. Various modalities of endoscopic therapy have been used to reduce recurrent bleeding, surgery, and mortality rates, and therefore, endoscopic intervention is a preferable procedure in acute gasrointestinal (GI) bleeding. In the past few decades, several endoscopic methods have been developed for hemostasis of gastrointestinal bleeding. Some of these are HPC, direct injection of fluids (e.g., diluted epinephrine or distilled water) into the bleeding lesion using disposable needles, mechanical devices such as endoclips, and APC. There have been several studies about the efficiency of these methods in gastrointestinal bleeding. Although APC is used especially for chronic radiation proctitis[4], watermelon stomach and ablation of Barrett’s esophagus, there are no current clinical studies about the application of APC in bleeding ulcers and for other causes of UGIB. APC therapy has various theoretical merits over contact-type thermal coagulation. First, depending on different power/flow settings, the burn depth can be preset between 0.5 mm and 3 mm, which is a particularly appropriate range for hemostasis in thin-walled duodenum and colon. Second, some bleeding points, such as those in the posterior wall or lesser curvature of the upper gastric body or the posterior wall of the duodenal bulb, may be difficult to approach. The no-touch technique in APC can make the approach easier by the arcing effect[2,5]. Wang et al[6] have compared APC and distilled water injection in treating high-risk bleeding ulcers, and they have reported that bleeding recurrence was 11% in the APC group and 27% in the distilled water injection group. They have concluded that endoscopic therapy is more effective than distilled water injection for preventing rebleeding in these patients, and no significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of surgery and mortality. There have been a few studies in which APC and HPC were compared for treatment of peptic ulcer bleeding[7]. Although HPC is the more commonly used method in active bleeding lesions[8], APC is not used as much as HPC for stopping gastrointestinal bleeding. In our study, APC appeared to be more effective in initial hemostasis, but rebleeding rates were similar with both techniques. Bleeding recurrence has consistently been identified as the most important prognostic factor for mortality[9]. Arresting recurrence of bleeding can decrease the rate of morbidity and mortality from UGIB. Cipolletta et al[7] have reported that initial hemostasis rates were 95% and 95.2%, and recurrent bleeding rates were 21% and 15% in HPC and APC group, respectively, and there was no significant difference between the groups in the rate of recurrent bleeding[2]. Although rebleeding rates were much lower in the APC group, we found no significant difference in the rebleeding rates between the groups. Skok et al[10] have reported that clinically and endoscopically diagnosed bleeding recurred in 14% of patients in the APC group, and 18% of patients in the sclerotherapy group. Although these controlled trials had similar hemostatic efficacy, the patients treated with APC had noticeably lower rebleeding rates.

The theoretical advantages of APC include its ease of application, speedy treatment of multiple lesions in the case of arteriovenous malformations or wide areas (the base of resected polyps or tumor bleeding), and safety due to reduced depth of penetration[11]. Superficial ulceration occurs following APC, which typically heals within 2-3 wk. Despite theoretical safety advantages due to reduced depth of penetration, all of the complications that have been reported with other thermal hemostasis techniques may occur. The first series of clinical applications of APC in gastrointestinal endoscopy was published in 1994[12]. Although no specific data were provided to assess the outcome for GI bleeding, the authors have described the technique as successful[12]. Several centers have subsequently reported experience with this technique in the management of GI bleeding[2,12]. However, few randomized studies comparing with APC with other hemostasis techniques have been performed, and our study is believed to be the first comparison of these two techniques in UGIB in recent years. APC application had better rates of initial hemostasis than HPC in our study.

The heater probe has a thermocouple at the tip of the probe that can heat up quickly and achieve tissue coagulation. As a result, deep coagulation is feasible with the heater probe, but this effect may risk perforation. As mentioned above, few studies have directly compared APC to other methods, especially HPC, for achieving hemostasis. In conclusion, APC is one of the effective hemostatic methods in bleeding peptic ulcers. Larger multicenter trials are necessary to confirm these data.

Contact thermal coagulation with heater probe coagulation (HPC) and argon plasma coagulation (APC) are the hemostatic methods used for the treatment of bleeding peptic ulcers. Few studies have directly compared the use of epinephrine injection plus APC versus epinephrine injection plus HPC for achieving hemostasis.

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is a common and life-threatening medical emergency. Contact thermal coagulation with HPC and APC are among the hemostatic methods for treatment of bleeding peptic ulcers. In this study, the authors demonstrate that there is a higher initial hemostasis rate in APC when compared with HPC in ulcer bleeding.

Few randomized studies have compared APC with other hemostasis techniques, and the study is believed to be the first comparison of these two techniques with additional use of epinephrine injections for UGIB in recent years. This study suggests that APC could be used instead of HPC, and that APC could provide clinicians with an effective alternative method to stop bleeding ulcers, due to its high rate of primary hemostasis and low rate of rebleeding.

This study may encourage clinicians without experience in APC to use the technique for treatment of ulcer bleeding.

APC is a non-contact method of delivering a high-frequency monopolar current through ionized and electrically conductive argon gas. Devices are applied directly to the bleeding point to cause coagulation and thrombosis in HPC. The heater probe is pushed firmly onto the bleeding lesion to apply tamponade and deliver defined pulses of heat energy.

The authors have compared the effectiveness of APC and HPC for ulcer bleeding. They have concluded that APC is superior to HPC for initial hemostasis. This was a well-designed study because the patients were assigned to two groups at random.

| 1. | Cappell MS, Friedel D. Acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: endoscopic diagnosis and therapy. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92:511-550, vii-viii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Vargo JJ. Clinical applications of the argon plasma coagulator. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:81-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Palmer K. Management of haematemesis and melaena. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80:399-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Karamanolis G, Triantafyllou K, Tsiamoulos Z, Polymeros D, Kalli T, Misailidis N, Ladas SD. Argon plasma coagulation has a long-lasting therapeutic effect in patients with chronic radiation proctitis. Endoscopy. 2009;41:529-531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Malick KJ. Clinical applications of argon plasma coagulation in endoscopy. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2006;29:386-391; quiz 392-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang HM, Hsu PI, Lo GH, Chen TA, Cheng LC, Chen WC, Lin CK, Yu HC, Chan HH, Tsai WL. Comparison of hemostatic efficacy for argon plasma coagulation and distilled water injection in treating high-risk bleeding ulcers. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:941-945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cipolletta L, Bianco MA, Rotondano G, Piscopo R, Prisco A, Garofano ML. Prospective comparison of argon plasma coagulator and heater probe in the endoscopic treatment of major peptic ulcer bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:191-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Barkun AN, Bardou M, Kuipers EJ, Sung J, Hunt RH, Martel M, Sinclair P. International consensus recommendations on the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:101-113. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Turner IB, Jones M, Piper DW. Factors influencing mortality from bleeding peptic ulcers. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991;26:661-666. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Skok P, Krizman I, Skok M. Argon plasma coagulation versus injection sclerotherapy in peptic ulcer hemorrhage--a prospective, controlled study. Hepatogastroenterology. 2004;51:165-170. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Freeman ML. New and old methods for endoscopic control of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2003;68 Suppl 3:62-65. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Grund KE, Storek D, Farin G. Endoscopic argon plasma coagulation (APC) first clinical experiences in flexible endoscopy. Endosc Surg Allied Technol. 1994;2:42-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Peer reviewer: Yoshio Yamaoka, MD, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Medicine/Gastroenterology, Baylor College of Medicine and VA Medical Center (111D), 2002 Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030, United States

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Zhang DN