INTRODUCTION

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease of unknown etiology. The pathogenesis of CD is multifactorial, and several fact

ors have been implicated in its development including genetic and environmental ones[1]. Differences in incidence rates across age, time, and geographic areas suggest that environmental factors are implicated in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), but only cigarette smoking and appendectomy have consistently been identified as risk factors, the former being the one with the greatest impact on both CD development and disease behavior. The disease is more frequent in active smokers than in non-smokers[2,3], and smoking may alter the natural course of CD since smokers are more likely to develop complications and relapses, and to need surgery[4].

There is evidence that interventions designed to facilitate smoking cessation may improve the course of the disease[5]. This article reviews the available data on smoking and its effects among patients with an established diagnosis of CD.

CLINICAL COURSE AND PROGNOSIS OF CD IN SMOKERS

It is well known that CD is more common in smokers[3]. The relationship between smoking and worsening of the clinical course of the disease has also been established, though the underlying mechanisms are complex and are still subject to research. Of note is the fact that in the case of ulcerative colitis (UC), the effects of smoking are the opposite of those seen in CD. The potential mechanisms explaining such opposing behavior include the different effects of smoking upon cellular and humoral immune function in both diseases, their cytokine profiles, and bowel wall motility and permeability[6].

Among the elements contained in tobacco smoke, it seems clear that nicotine has the greatest impact upon the clinical course of CD[7]. However, it has been recently established that tobacco glycoprotein may be responsible for promoting a Th1 cell response[8], while nicotine maintains its relevance as the cause of anti-inflammatory action in UC[9]. Smokers show an increased production of reactive oxygen species and a lessened antioxidant capacity[10]; this, in turn, could act synergically with oxidative stress in CD[11]. Moreover, environmental factors may interact with genetic factors. In this sense, recent research has demonstrated that smoking may influence the gene expression profile of the colonic mucosa in CD patients[12].

Smoking has been associated with a poorer prognosis of CD and a worse quality of life[13]. Holdstock et al[14] reported for the first time that CD patients who were active smokers had an increased number of disease relapses and more severe pain; this was also associated with an increased probability of hospital admission and intestinal resection among patients with ileal involvement. This increased relapse rate was later estimated to be two-fold higher among smokers in a Canadian prospective study involving 152 CD patients[15].

Some epidemiological factors such as gender or disease location may influence the impact of smoking habits on CD outcomes. Most data on the impact of smoking on CD natural history come from the studies performed in the Hôpital Saint Antoine in Paris[16-18]. One of their first studies included 400 consecutive CD patients who were specifically interviewed to assess the effects of smoking upon the long-term course of the disease[16]. The need for corticosteroids and immunomodulators was greater among smokers, but no differences were found in terms of intestinal resection requirements except in those patients who started smoking after CD diagnosis. In addition, the deleterious effect of smoking was found to be dose-dependent, and more marked among women. In a later study, the same authors underscored the existence of a poorer prognosis among women[18].

Exclusive colon involvement possibly does not imply a poorer disease course in smokers as compared to non-smokers. In another study published by the same French group that involved 622 CD patients, the risk of relapse was found to be significantly greater among patients with inactive disease and without colon involvement[17]. A multicenter survey involving 457 CD patients from 19 European countries evaluated several clinical parameters at the time of disease diagnosis. Prescription of corticosteroids or immunomodulators - as a surrogate marker of a less favorable disease course - proved greater among smokers within the first year from disease diagnosis[19]. The proportion of individuals with ileal involvement was likewise significantly greater among smokers, in agreement with the findings in our own setting[20]. In fact, these higher surgical requirements among smokers could be related to a more frequent ileal involvement[21].

The negative effects of smoking seem to be dose-dependent, with the risk of a poor disease prognosis being particularly high among heavy smokers. Lindberg et al[22], in a series of 231 CD patients, reported that heavy smokers (over 10 cigarettes/d) presented an increased risk of surgery at 5 and 10 years from diagnosis as compared to patients who never smoked (OR 1.14 and 1.24, respectively). The risk for further operations was even higher, with an OR at 10 years of 1.79. In another study, the proportion of time with intestinal inflammatory activity during follow-up was reported to be 37% among non-smokers, 46% among patients who smoked less than 10 cigarettes/d, and 48% among heavy smokers[23]. Surprisingly, a recent study has reported no unfavorable clinical course in smokers, though passive smokers did show a poorer course[24].

Smoking has been correlated to a lesser prevalence of inflammatory (non-stricturing, non-penetrating) behavior of the disease, thus suggesting that tobacco consumption influences progression towards fistulizing or stricturing disease[22,25-27]. Available data are contradictory when assessing the risk of perianal disease, since it was included in the definition of the fistulizing CD pattern in the initial Vienna phenotypic classification of CD[28], but not in the Montreal adaptation[29]. Of note is the fact that phenotypic characteristics may differ greatly according to the ethnical origin of the studied population. Thus, for the French Canadian population, the phenotypic pattern has been differentiated from that of other Caucasian populations, with an important trend towards aggressive fistulizing behavior[30]. In this population, the association between smoking and CD is strong enough to have possible implications. The lack of association between smoking and CD has now been established in Jewish patients in Israel. The stronger genetic tendency in CD may contribute to this discrepancy[31].

POST-SURGICAL RECURRENCE IN SMOKERS

Intestinal resection still remains a cornerstone in the management of CD despite the availability of biologic agents and the widespread use of immunomodulators. Recently, two independent studies reported a cumulative probability of undergoing abdominal surgery of about 40% and 60% within five and ten years from disease diagnosis, respectively, in an adult hospital-based and in a pediatric population-based cohort of CD patients[32,33]. However, disease recurrence is almost the rule after a “curative” resection and, for this reason, preventive algorithms have been repeatedly proposed[34,35]. Although it is still to be established whether all patients should start immunomodulators after surgery or not, all authors agree that smoking cessation must be strongly encouraged. In fact, many studies have found that active smoking is firmly correlated with an increased risk of CD postoperative recurrence[36]. This has been recently confirmed in two large studies that found smoking to be an independent risk factor for surgical recurrence (re-operation)[37,38]. Postoperative recurrence usually occurs among patients operated on because of ileal disease, and the harmful effect of tobacco seems to be greater in patients with ileal involvement[17]. However, the results of most of these studies are handicapped by methodological aspects. Firstly, most of them are retrospective; smoking habits may vary with time and this is not always registered in medical records. Secondly, the effects of tobacco may be influenced by some potential confounding factors such as gender[39,40], daily cigarette dose[41], or even ethnicity[41,42], and these have not always been taken into account. Finally, definitions of “active smoker” or “former smoker” are heterogeneous between studies; this is especially important when evaluating smoking cessation, since the effect of giving up smoking seems to be clinically relevant from 1 year on[43].

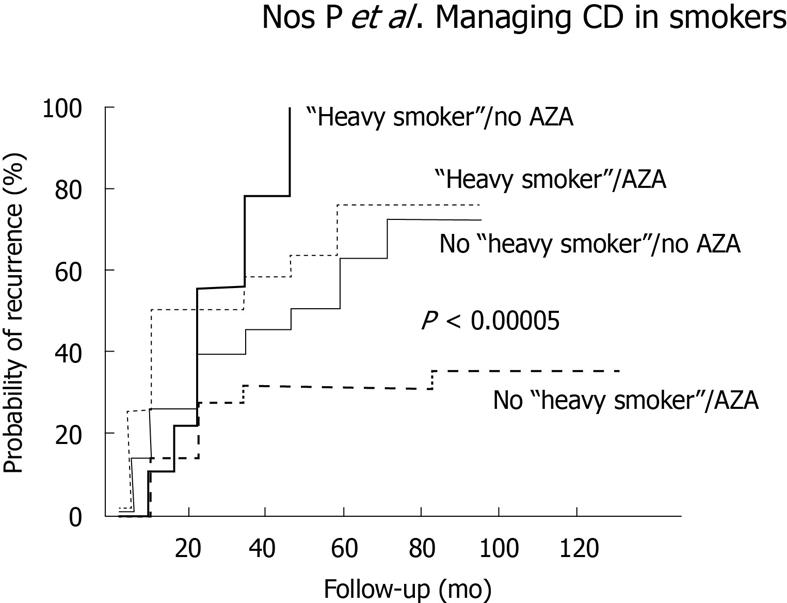

Cottone et al[44] reported the results of a retrospective study which included 182 CD patients who underwent intestinal resection, 109 of whom had an endoscopic assessment for mucosal recurrence 1 year after surgery. The authors found, for the first time, that active smoking was an independent risk factor for endoscopic, clinical, and surgical recurrence. Moreover, this deleterious effect of tobacco on clinical recurrence was dose-dependent. The major drawbacks of this study were that it did not accurately assess the severity of endoscopic lesions and that preventive treatment (if any) was not taken into account. Cortés et al[45] recently reported the results of the first prospective study assessing factors associated with endoscopic recurrence. The study included 152 patients participating in three prospective trials that evaluated the efficacy of diagnostic procedures or different preventive strategies for postoperative recurrence and in which endoscopic and clinical monitoring was systematically performed. Smoking and thiopurine use were the only independent predictors of significant postoperative recurrence as defined by the occurrence of clinical recurrence and/or Rutgeerts grade 3 or 4 of endoscopic recurrence (Figure 1). Once again, this risk was much more marked among heavy smokers (patients who smoked > 10 cigarettes/d). It has to be noted that, despite the suggestion that the harmful effect of tobacco in CD might be neutralized by the use of immunomodulators[16], this does not seem to be the case in all clinical settings; as regards postoperative recurrence, two different studies have identified both azathioprine use and active smoking as independent factors associated with both endoscopic and surgical recurrence[38,45].

Figure 1 Cumulative probability of relevant recurrence (grade 3 or 4 of endoscopic and/or clinical recurrence) depending on preventive use of azathioprine and active smoking.

Reproduced from Cortés et al[45] with permission. AZA: Azathioprine.

SMOKING INFLUENCING THERAPEUTIC RESPONSE

Although it has been proven that smoking increases therapeutic requirements in CD (steroids, immunomodulators, surgery), only a few studies addressing the impact of smoking on drug efficacy have been performed to date.

Some studies have tried to assess the influence of smoking habits on the response to infliximab. Parsi et al[46] aimed to identify those demographic and clinical parameters associated with the response to infliximab in 59 patients with luminal CD. Logistic regression analysis found that only smoking and the concomitant use of immunomodulators were independent predictors of response to one single infusion of the drug. Similar results were obtained in a subsequent study in 60 patients treated with a single infliximab infusion for refractory luminal CD[47]. However, a larger European study including 137 patients treated for luminal disease found that age, disease location and concomitant use of immunomodulators, but not smoking habits, were the only factors associated with clinical response in the multivariate analysis[48]. A North American study[49] performed with 122 patients who received one single infliximab infusion for refractory luminal CD did not find any predictor of response among several demographic and clinical factors, including smoking habits. Finally, an Italian multicenter study involved 382 patients who received infliximab for induction of remission in luminal CD (137 of them with a single infusion and 245 with a conventional three-infusion schedule)[50]; among several clinical parameters, only treatment with one single infusion and previous surgery were associated with a lesser probability of response in both univariate and multivariate analyses. All the above-mentioned studies also included patients with fistulizing CD, but no predictor of response (including smoking habits) was found in any of them.

In summary, despite initial data which suggested that active smoking reduced the likeliness to respond to one single infusion among patients with luminal CD, larger studies repeatedly found no association between smoking and infliximab response; however, it has to be said that most of these studies did not consider the tobacco dose.

The influence of smoking on other IBD-related drugs has been infrequently addressed. In this regard, a Spanish study evaluated for the first time the relationship between smoking and the response to thiopurines[51]. The study included 163 IBD patients (103 CD and 60 UC) who started thiopurine therapy because of steroid dependency and who were followed up in two Catalonian centers. Smoking habits at the time thiopurines were started were carefully assessed. No difference in the proportion of responders was found, in CD or in UC, suggesting that, once again, tobacco does not influence the efficacy of drug therapies in IBD. Results remained the same when several exploratory sub-analyses combining gender, disease location (colonic or ileal involvement, colonic or ileal isolated disease) and smoking habits (non-smokers, smokers, heavy smokers of > 10 cigarettes/d) were performed. Of note, CD responders who continued smoking had a higher rate of relapses during follow-up, although this did not lead to higher requirements of biological agents or surgery. Surprisingly, the authors found that treatment discontinuation because of thiopurine-related side effects was independently associated with active smoking in the multivariate analysis. This led to a reduced treatment efficacy among CD patients (as compared to UC) when evaluated by intention-to-treat analysis. Similarly, the largest survey of thiopurine-related toxicity in IBD patients reported to date, which included 3900 IBD patients treated with thiopurines from the Spanish ENEIDA Register [a nationwide register of IBD patients promoted by the Spanish Working Group in IBD (GETECCU)] found that both hepatotoxicity and acute pancreatitis were significantly more frequent in CD as compared to UC, although the smoking status information when starting thiopurines was not available[52].

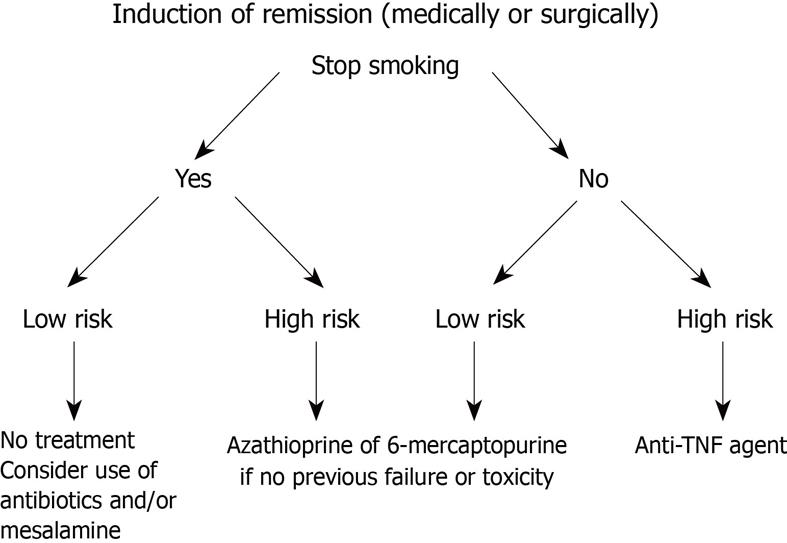

In summary, it seems clear that active smoking increases the risk of a more disabling course of CD, particularly in patients with ileal disease, women, and heavy smokers. This harmful effect might be genetically modulated, as seen in certain ethnic groups. Once those populations at risk are identified, interventional measures to ensure smoking cessation should be considered (Figure 2). If the patient fails in giving up smoking, more intensive CD treatment strategies such as earlier use of immunomodulators and/or biological agents should be taken into account in order to anticipate complications.

Figure 2 Algorithm for patient in medically or surgically induced remission.

Low risk is defined as long-standing, short segment fibrostenotic disease without or with minimum active inflammation. TNF: Tumor necrosis factor.

INTERVENTIONS FOR SMOKING CESSATION: ARE THEY EFFECTIVE?

The strongest evidence of the deleterious effect of tobacco consumption upon the course of CD is precisely the beneficial consequences of smoking cessation[5]. In the cohort study published by Cosnes et al[17], patients were followed up for 12-18 mo and a lower relapse risk was observed among those patients who stopped smoking for at least 6 mo. In ex-smokers, the clinical course was similar to that seen in patients who have never smoked.

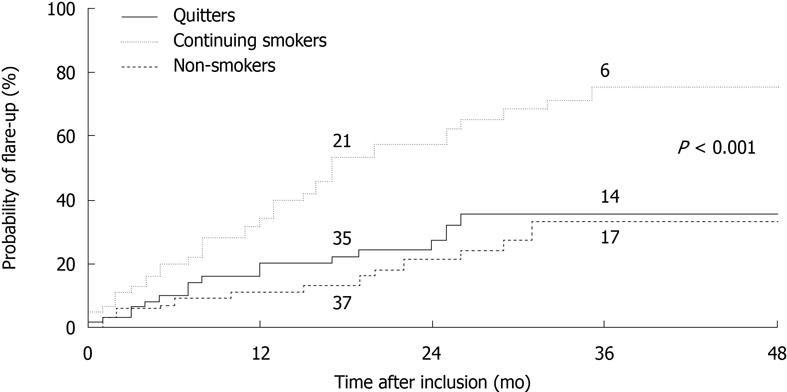

There is no doubt regarding the beneficial effects of smoking cessation upon the clinical course of CD. Such benefit might be even greater than that afforded by the use of thiopurines as maintenance therapy. The only interventional study published to date included 474 consecutive smokers with CD who were offered a smoking cessation program[18]. Patients who stopped smoking for more than one year (quitters) were included in a prospective follow-up study comparing disease course and therapeutic requirements with two control groups - continuing smokers and non-smokers - matched for age, gender, disease location and activity. Fifty-nine patients were able to quit smoking (12%). After a median follow-up of 29 mo, the risk of flare-up in quitters did not differ from that in non-smokers, and was lower than that of smokers (Figure 3). Steroid and immunomodulator requirements were similar among quitters and non-smokers, but greater among smokers. Finally, the risk of surgery was not significantly different between the three groups. Interestingly, the authors found that the physician in charge, previous intestinal surgery, high socioeconomic status and, in women, oral contraceptive use, were predictors of quitting tobacco consumption.

Figure 3 Relapse (flare-up) risk during follow-up of Crohn’s disease in continuing smokers, ex-smokers (quitters) and patients who have never smoked.

The stated P-value corresponds to comparison between the quitters and continuing smokers. Reproduced from Cosnes et al[18] with permission.

Despite the negative effect of smoking on health, and specifically on the clinical course of CD, smoking cessation is not an easy matter. Management of smokers is based on two complementary interventions: behavioral intervention and drug therapy. Physicians must remember the “four As” needed to correctly address this topic: (1) asking about current smoking habit; (2) advising them to stop; (3) assisting the patient by way of the available methods; and (4) arranging follow-up. It is very important to stress the importance of smoking cessation, since patients who are aware of the strongly negative impact of the habit upon the course of the disease will find it easier to stop smoking. Unfortunately, CD patients are too often unaware of the risks that smoking poses for their disease, thus indicating the need for increased patient information with regard to the effects of smoking on CD[53,54].

Recently, an interesting study designed to increase the motivation to stop smoking involved 140 smokers without CD[55]. Individuals were informed about the characteristics of CD, and underwent a genetic study (NOD2/CARD15 mutations) in order to classify them according to the risk of developing the disease. The results confirmed the hypothesis that increased information on the genetic burden of CD could modify the intention to quit smoking, to the extent that those individuals at higher risk showed a greater willingness to stop smoking.

Behavioral interventions designed to stop smoking

Behavioral interventions designed to facilitate smoking cessation include specific warnings from the general practitioner, intensive advice or counseling by specialists on disease-related risks, and supportive measures in the form of written material or telephone calls[5].

Simple warning by physicians to stop smoking has shown some usefulness in the studies conducted by the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Review Group[56], though the effect is relatively poor[57]; assuming an unassisted quitting rate of 2%-3%, a brief advice intervention can increase quitting by a further 1%-3%. Direct comparison of intensive vs minimal advice has shown a small advantage for intensive advice [relative risk (RR) 1.37, 95% confidence interval (95% CI): 1.20-1.56]. Additional components appear to exert only a minor effect, though a small additional benefit is derived from more intensive interventions compared to very brief interventions.

Behavioral interventions are useful, especially when combined with drug therapy, and particularly over the short term. Motivational interviewing is a directive patient-centered style of counseling designed to help people to explore and resolve ambivalence about behavior change. It was developed as a treatment for alcohol abuse, but may help smokers to make a successful attempt to quit smoking[58]. Innovative effective smoking cessation interventions are required to appeal to those who are not accessing traditional cessation services. Mobile phones are widely used and are now well integrated into daily life, particularly among young adults - as most CD patients are at disease onset. Mobile phones are a potential medium for the delivery of health programs such as those designed to facilitate smoking cessation, but current evidence shows no effect of mobile phone-based smoking cessation interventions upon long-term outcome[59]. Pooled data from the Internet and mobile phone programs show statistically significant increases in both short- and long-term self-reported quitting (RR 2.03, 95% CI: 1.40-2.94). While short-term results are positive, more rigorous studies of the long-term effects of mobile phone-based smoking cessation interventions are needed.

Many European centers have outpatient clinics specifically targeted to help smoking cessation by means of a multidisciplinary approach (with nurses, psychologists, pneumologists and general practitioners), but drug therapy is almost universally used in these clinics as a complement to behavioral interventions.

Drug therapy

Pharmacological smoking cessation aids are recommended for all smokers who are trying to quit, unless contraindicated. The available drugs include the following.

Nicotine replacement products: Such products offer a way to administer nicotine without smoking. They can be used in the form of patches, chewing gum, or nasal spray formulations. The aim of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) is to temporarily replace much of the nicotine from cigarettes to reduce motivation to smoke and nicotine withdrawal symptoms, thereby easing the transition from cigarette smoking to complete abstinence. A recent Cochrane review[60] identified 132 trials on the use of NRT in people willing to quit smoking. Of these, 111 trials involving over 40000 participants contributed to the primary comparison between any type of NRT and a placebo or non-NRT control group. The RR of abstinence for any form of NRT relative to control was 1.58 (95% CI: 1.50-1.66). The pooled RR for each type were 1.43 (95% CI: 1.33-1.53, 53 trials) for nicotine gum, 1.66 (95% CI: 1.53-1.81, 41 trials) for nicotine patch, 1.90 (95% CI: 1.36-2.67, 4 trials) for nicotine inhaler, 2 (95% CI: 1.63-2.45, 6 trials) for oral tablets/lozenges, and 2.02 (95% CI: 1.49-3.73, 4 trials) for nicotine nasal spray. The effects were largely independent of the duration of therapy, the intensity of the provided additional support, or the setting in which NRT was offered. The effect was similar in a small group of studies that aimed to assess the use of NRT obtained without a prescription. In highly dependent smokers there was a significant benefit of 4 mg gum compared with 2 mg gum, but weaker evidence of a benefit from higher doses in patch form. There was evidence that combining a nicotine patch with a rapid delivery form of NRT is more effective than a single type of NRT. Only one study directly compared NRT to another drug treatment modality. In this study the smoking cessation rates with nicotine patch were lower than with the antidepressant bupropion.

Bupropion: While not a substitute for nicotine, this drug reduces the anxiety associated with not smoking. Bupropion is an atypical antidepressant that acts as a norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor. Initially researched and marketed as an antidepressant, bupropion was subsequently found to be effective as a smoking cessation aid. Conversely to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (e.g. fluoxetine), the antidepressants bupropion and nortriptyline contribute to long-term smoking cessation. It has been suggested that the mode of action of bupropion and nortriptyline could be independent of their antidepressant effect, and that their efficacy is similar to that of nicotine replacement[61].

Varenicline: This new smoking dishabituation agent acts by blocking the nicotinic receptors and induces similar effects to that of nicotine, counteracting the craving to smoke, lessening the withdrawal syndromes, and reducing the gratifying and reinforcing effects of smoking. Varenicline was developed as a nicotine receptor partial agonist from cytisine, a widely used drug in Central and Eastern Europe for smoking cessation. Nicotine receptor partial agonists may help people to stop smoking by a combination of maintaining moderate levels of dopamine to counteract withdrawal symptoms (acting as an agonist) and reducing smoking satisfaction (acting as an antagonist). The first reports of trials with varenicline were published in 2006[62]. This drug offers higher efficacy rates (smoking cessation) than those of the existing alternatives[63]. Varenicline increased by 2- and 3-fold the chances of successful long-term smoking cessation as compared with pharmacologically unassisted quitting attempts. There is a need for independent community-based trials of varenicline to test its efficacy and safety in smokers with varying co-morbidities and risk patterns. Likewise, there is a need for further trials of the efficacy of treatment extended beyond 12 wk.

In February 2008, the United States FDA issued a public health advisory note, reporting a possible association between varenicline and an increased risk of behavior change, agitation, depressed mood, and suicidal ideation and behavior[64]. The possible risks of serious adverse events occurring while using varenicline or bupropion should always be weighed against the significant health benefits of quitting smoking that include not only a better prognosis for CD but also a reduction in the chance of developing lung or heart disease, and cancer.

MANAGEMENT OF SMOKING RELAPSE

Less than 10% of all patients who quit smoking without medical help are able to maintain abstinence over the long term[65]. Interventions, whether pharmacological or surgical, increase the long-term cessation rates as compared to control interventions, though there is a permanent reduction in the general success rates due to the fact that a proportion of individuals who are initially able to stop smoking subsequently relapse over time.

At present there is insufficient evidence to support the use of any specific behavioral intervention for helping smokers who have successfully quit for a short time to avoid relapse[66]. The verdict is strongest for interventions focusing on identifying and resolving tempting situations, as most studies have been concerned with these. There is little research available regarding other behavioral approaches. Extended treatment with varenicline may prevent relapse, though extended treatment with bupropion is unlikely to have a clinically important effect. Studies of extended treatment with nicotine replacement are needed.

DIFFERENT APPROACH TO CD PATIENTS WHO CONTINUE SMOKING

When compared to similar data for the general population, patients with CD are not found to be more refractory to smoking cessation[67]. CD patients must be informed of the importance of smoking cessation for the course of their disease, and individualized medical intervention should be established to reach this objective. This is particularly important in smoking women with CD. Nicotine patch replacement therapy during the first 6-12 wk of abstinence is appropriate in heavy smokers and in smokers with a high degree of tobacco dependency. If, despite reinforced medical advice, the patient is unable to quit smoking, referral to a specific smoking cessation clinic is recommendable. If this is not possible, then the physician should offer behavioral and drug treatment support.

Varenicline is likely to be clinically and cost-effective for smoking cessation, assuming that each user makes a single attempt to quit smoking. The key area of uncertainty concerns the long-term experience of subjects who have remained abstinent beyond 12 mo. Guidelines issued by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence in July 2007 state that varenicline is recommended under its licensed indications as an option for smokers who have expressed their wish to quit smoking, and that varenicline should normally be prescribed only as part of a behavioral support program[68,69]. In the presence of depressive symptoms or other contraindications to the use of these drugs, NRT may be used.

Whenever a CD patient is not able to stop smoking, a close monitoring (clinical and/or even endoscopic) is recommended and early introduction of more intensive therapeutic strategies (immunomodulators and/or biological agents) should be considered, especially in women with ileal involvement.

Peer reviewer: Stephen M Kavic, MD, FACS, Assistant Professor of Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Maryland School of Medicine, 22 South Greene Street, Room S4B09, Baltimore, MD 21201, United States

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Ma WH