Published online Aug 14, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i30.3526

Revised: March 29, 2011

Accepted: April 5, 2011

Published online: August 14, 2011

AIM: To evaluate virological response to adefovir (ADV) monotherapy and emergence of ADV-resistant mutations in lamivudine (LAM)-resistant chronic hepatitis B patients.

METHODS: Seventy-seven patients with documented LAM resistance who were treated with 10 mg/d ADV for > 96 wk were analyzed for ADV resistance.

RESULTS: At week 48 and 96, eight (10%) and 14 (18%) of 77 LAM-resistant patients developed the ADV-resistant strain (rtA181V/T and/or rtN236T mutations), respectively. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA levels during therapy were significantly higher in patients who developed ADV resistance than in those who did not. Incidence of ADV resistance at week 96 was 11%, 8% and 6% among patients with complete virological response (HBV DNA level < 60 IU/mL); 0%, 5% and 19% among patients with partial virological response (HBV DNA level ≥ 60 to 2000 IU/mL); and 32%, 34% and 33% among patients with inadequate virological response (HBV DNA levels > 2000 IU/mL) at week 12, week 24 and week 48, respectively. HBV DNA levels > 2000 IU/mL at week 24 showed best performance characteristics in predicting ADV resistance.

CONCLUSION: Development of ADV resistance mutations was associated with HBV DNA levels, which could identify patients with LAM resistance who are likely to respond to ADV monotherapy.

- Citation: Sinn DH, Lee HI, Gwak GY, Choi MS, Koh KC, Paik SW, Yoo BC, Lee JH. Virological response to adefovir monotherapy and the risk of adefovir resistance. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(30): 3526-3530

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i30/3526.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i30.3526

Lamivudine (LAM) has been the most popular antiviral agent for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B for many years, but its efficacy is hampered by the high incidence of drug resistance[1]. Adefovir dipivoxil (ADV) is a nucleotide analog that exhibits activity against wild-type and LAM-resistant hepatitis B virus (HBV)[2-4]. Early studies have demonstrated potent viral suppression of LAM-resistant HBV by either switching to or adding ADV to LAM[5]. However, ADV-resistant strains have been reported after either switching to or adding ADV in patients with LAM resistance, and several recent clinical studies have found that combined LAM with ADV is associated with improvements in virological response and lower rates of ADV resistance than sequential ADV monotherapy[6-8]. Thus, recent guidelines suggest adding ADV to LAM as a better approach than sequential monotherapy for patients with LAM resistance[9-12].

Although ADV add-on therapy represents a new paradigm that is highly effective at restoring viral suppression and preventing the emergence of resistance in patients with LAM resistance[13], the higher cost of add-on therapy may allow ADV monotherapy to retain its role in selected patients, particularly in developing countries[14]. In clinical practice, some patients with LAM resistance do respond to ADV monotherapy[15]. Identification of patients who may be sufficiently treated with ADV monotherapy alone may reduce medical costs in areas where resources are limited.

HBV DNA levels on treatment may help select patients who are likely to respond to ADV monotherapy. Maintenance of undetectable HBV DNA levels during treatment with nucleoside/nucleotide analogs has been suggested as a desirable endpoint[10]. Recently proposed “on-treatment strategy” for patients receiving oral nucleoside/nucleotide therapy is also based on HBV DNA levels[16]. On-treatment monitoring strategies are based on the nature of virological response during treatment, and HBV DNA levels during treatment may be a valuable predictor of treatment response to ADV monotherapy.

The aim of this study was to establish whether HBV DNA levels during treatment are associated with the emergence of genotypic ADV resistance. We studied HBV DNA levels at weeks 12, 24 and 48 after the start of ADV monotherapy among LAM-resistant patients who had received ADV monotherapy for > 96 wk and assessed genotypic resistance to ADV at weeks 48 and 96.

Data were collected retrospectively from 85 LAM-resistant chronic hepatitis B patients who started ADV monotherapy between March 2004 and May 2006, and maintained ADV monotherapy for at least 96 wk at the Samsung Medical Center, Seoul, Korea. All 85 patients were treated with LAM for chronic HBV infection and experienced virological breakthrough (VB), which was defined as an increase in the level of HBV DNA of at least 1 log10 IU/mL from the lowest point during treatment. Serum samples were collected every 3 mo during treatment and kept at -80°C until mutation analyses were performed. Eight patients were excluded from analyses for the following reasons: (1) serum samples were not available for six patients; and (2) an ADV-resistant strain (rtA181V/T) was present at baseline in two patients. Finally, a total of 77 patients were included in this study. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Samsung Medical Center.

Routine biochemical tests were performed by standard procedures every 12 wk during therapy. Hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), and hepatitis B e antibody were tested by electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Elecsys; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, United States). LAM resistance was tested with direct sequencing (ABI 3130 Genetic Analyzer; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States).

HBV DNA was quantified using the COBAS TaqMan HBV test (detection limit of 12 IU/mL, Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, NJ, United States) at the onset of ADV treatment (baseline), and at weeks 12, 24 and 48 using stored serum samples. Virological response was defined as complete virological response (CVR, HBV DNA level < 60 IU/mL); partial virological response (PVR, HBV DNA levels ≥ 60 to 2000 IU/mL); and inadequate virological response (IVR, HBV DNA levels > 2000 IU/mL)[13]. VB was defined as an increase in the level of HBV DNA of at least 1 log10 IU/mL from the lowest point during treatment[13].

Genotype resistance to ADV was determined at baseline and at weeks 48 and 96 by direct sequencing after amplification of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products. To detect mutations, PCR amplification was performed using the following primers: external primers were RTF (5’-tat gtt gcc cgt ttg tcc tc-3’, position 460-479) and RTR (5’-tga cat act ttc caa tca ata gg-3’, position 970-992); internal primers were RTNF (5’-aaa acc ttc gga cgg aaa ct-3’, position 574-593) and RTNR (5’-tgc ggt aaa gta ccc caa ct-3’, position 895-914). The PCR-amplified DNA was purified by using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Purified DNA was treated with an ABI Prism BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems). The primers used for direct sequencing were RTNS and RTNR. DNA sequencing was performed in both directions by an Applied Biosystems 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). In this study, ADV resistance was defined as the presence of mutations that confer resistance to ADV, which were rtN236T and/or rtA181V/T[17,18].

Differences between patient groups were tested using t tests or Mann-Whitney U tests, as appropriate, for numeric variables, and χ2 tests or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate, for categorical variables. For statistical analysis, HBV DNA levels < 12 IU/mL were considered to be 12 IU/mL. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of HBV DNA levels were calculated for the prediction of genotypic resistance to ADV at week 96. Receiver operator curve (ROC) analysis was performed to compare the performance of HBV DNA levels at each time points. Statistical analysis was conducted using PASW Statistics 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Baseline characteristics of enrolled patients are shown in Table 1. At week 48, 8 (10%) of 77 LAM-resistant patients had developed the rtA181V/T and/or rtN236T mutations. At week 96, 14 (18%) of 77 LAM-resistant patients had developed rtA181V/T and/or rtN236T mutations (Table 2).

| Variables | |

| No. of patients | 77 |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 49.3 ± 11.7 |

| Female: Male (n, % male) | 18: 59 (77%) |

| HBeAg positive (n, % positive) | 21: 56 (73%) |

| ALT (U/L, median, range) | 119 (25–926) |

| AST (U/L, median, range) | 77 (30–483) |

| Albumin (g/dL, median, range) | 4.0 (2.6–4.6) |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL, median, range) | 1.0 (0.3–4.0) |

| Prothrombin time (INR, median, range) | 1.1 (0.9–1.7) |

| Baseline creatinine level (mg/dL, mean ± SD) | 0.90 ± 0.13 |

| Creatinine level at weeks 96 (mg/dL, mean ± SD) | 0.94 ± 0.16 |

| LAM resistance mutation profile (n, %) | |

| rtM204I ± rtL180M | 48 (62%) |

| rtM204V ± rtL180M | 29 (38%) |

| Variables | Week 48 | Week 96 |

| rtA181T | 5 | 5 |

| rtA181V | 2 | 5 |

| rtA181V + rtN236T | 1 | 2 |

| rtA181T + rtN236T | 0 | 2 |

| Total n (%) | 8 (10) | 14 (18) |

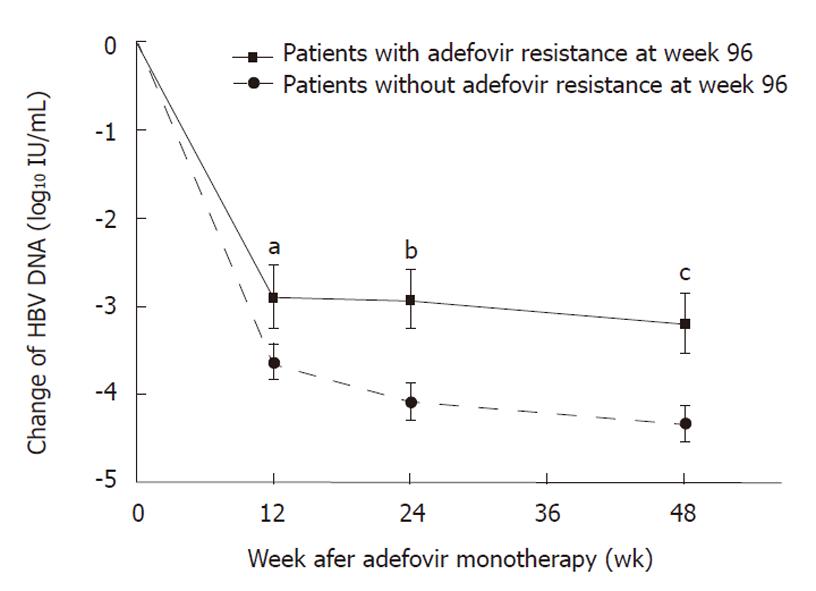

HBV DNA levels during treatment were significantly lower in patients who did not develop ADV resistance than in those who did, while pretreatment HBV DNA levels were not significantly different (Table 3). The degree of reduction of HBV DNA level was also significantly greater among patients who developed ADV resistance (Figure 1). There was a significant difference in the incidence of ADV resistance at week 96 according to HBV DNA levels at week 12 (P = 0.007), at week 24 (P = 0.008), and at week 48 (P = 0.022) (Table 4). Only 8% and 6% of patients with CVR at weeks 24 and 48 developed ADV resistance at week 96, whereas, > 30% of patients with IVR at weeks 12, 24 and 48 developed ADV resistance at week 96.

| HBV DNA level | ADV resistanceat week 96 (n = 14) | No ADV resistanceat week 96 (n = 63) | P value |

| Baseline (log10 IU/mL, mean ± SD) | 7.1 ± 0.7 | 6.8 ± 1.0 | 0.245 |

| Month 3 (log10 IU/mL, mean ± SD) | 4.2 ± 1.6 | 3.1 ± 1.6 | 0.027 |

| Month 6 (log10 IU/mL, mean ± SD) | 4.1 ± 1.4 | 2.7 ± 1.6 | 0.002 |

| Month 12 (log10 IU/mL, mean ± SD) | 3.9 ± 1.3 | 2.4 ± 1.5 | 0.002 |

| HBV DNA level | Patient number | ADV resistance at week 48 n (%) | ADV resistance at week 96 n (%) |

| Week 12a | |||

| < 60 IU/mL | 18 | 2 (11) | 2 (11) |

| ≥ 60 to < 2000 IU/mL | 21 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| > 2000 IU/mL | 38 | 6 (16) | 12 (32) |

| Week 24b | |||

| < 60 IU/mL | 26 | 2 (8) | 2 (8) |

| ≥ 60 to < 2000 IU/mL | 19 | 1 (5) | 1 (5) |

| > 2000 IU/mL | 32 | 5 (16) | 11 (34) |

| Week 48c | |||

| < 60 IU/mL | 34 | 2 (6) | 2 (6) |

| ≥ 60 to < 2000 IU/mL | 16 | 0 (0) | 3 (19) |

| > 2000 IU/mL | 27 | 6 (22) | 9 (33) |

The HBV DNA levels at weeks 12, 24 and 48 were tested for sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value for the prediction of ADV resistance at week 96 (Table 5). ROC curve analysis showed that the area under the curve in predicting ADV resistance was lowest at HBV DNA level ≥ 60 IU/mL at week 12 (area = 0.556, P = 0.51) and highest at HBV DNA level > 2000 IU/mL at week 24 (area = 0.726, P = 0.008).

| Variables | Adefovir resistance | Sensitivity (%, 95% CI) | Specificity | Positive predictive value | Negative predictive value |

| n (%) | (%, 95% CI) | (%, 95% CI) | (%, 95% CI) | ||

| HBV DNA level ≥ 60 IU/mL at Week 12 (n = 59) | 12 (20) | 85 (56–97) | 25 (15–38) | 20 (11–33) | 89 (63-98) |

| HBV DNA level > 2000 IU/mL at Week 12 (n = 38) | 12 (32) | 85 (56–97) | 58 (45–70) | 31 (18–48) | 84 (81–99) |

| HBV DNA level ≥ 60 IU/mL at Week 24 (n = 51) | 12 (24) | 85 (56–97) | 38 (26-51) | 23 (13–38) | 92 (73–98) |

| HBV DNA level > 2000 IU/mL at Week 24 (n = 32) | 11 (34) | 78 (48–94) | 66 (53–77) | 34 (19–53) | 93 (80–98) |

| HBV DNA level ≥ 60 IU/mL at Week 48 (n = 43) | 12 (28) | 85 (56–97) | 51 (38–63) | 28 (16–44) | 72 (56–84) |

| HBV DNA level > 2000 IU/mL at Week 48 (n = 27) | 9 (33) | 64 (35–86) | 71 (58–81) | 33 (17–53) | 90 (77–96) |

In this study, we found that on-treatment serum HBV DNA levels were associated with genotypic ADV resistance. Patients who developed ADV resistance showed higher HBV DNA levels at weeks 12, 24 and 48 after the start of ADV monotherapy. The incidence of ADV resistance was lowest among patients with CVR, and highest among patients with IVR (Table 4). These data suggest that risk of ADV resistance is low among patients who achieve CVR at weeks 12, 24 and 48 after ADV monotherapy, and they may continue ADV monotherapy. IVR at weeks 12, 24 and 48 was associated with development of ADV resistance, and ADV monotherapy should not be continued. Patients with PVR at weeks 12 and 24 showed low incidence of ADV resistance, and may continue ADV monotherapy with careful follow-up, but patients with PVR at weeks 48 may not continue ADV monotherapy because of significant risk of ADV resistance at week 96. The best predictor of ADV resistance was IVR at week 24 (Table 5).

The findings of this study are in line with the recently proposed “on-treatment strategy” for patients receiving oral nucleoside/nucleotide therapy[13]. Keeffe et al[13] have suggested that management strategies should be changed for patients with IVR response at week 24. Shin et al[19] also have described the importance of HBV DNA levels on treatment among patients with LAM resistance who received ADV monotherapy. They have reported that patients who had HBV DNA levels < 200 IU/mL at week 48 were unlikely to develop VB and genotype mutations. Chen et al[20] have reported that ADV resistance was associated with higher HBV DNA levels and lower HBV DNA reduction during the first 6 mo of ADV treatment, compared to patients who did not develop ADV resistance. Gallego et al[21] also have shown that initial virological response (reduction ≥ 4 log10 IU/mL) in HBV DNA at 6 mo is an important factor for predicting treatment outcome. These studies, as well as the present study, suggest that HBV DNA level during treatment is a valuable parameter for making early decisions regarding the continuation of ADV monotherapy or switching to another therapy in patients who show LAM resistance[19].

For patients with LAM resistance, adding ADV is a better approach than switching to ADV, as has been demonstrated by several studies[6-12]. However, because of the higher cost of add-on therapy, in areas with limited resources, ADV monotherapy may still be considered. If so, these data suggest that ADV monotherapy may be tried for up to 24 wk, depending on virological response. Patients who show favorable virological response may continue ADV monotherapy.

The cumulative probability of ADV resistance in our series was 10% and 18% at weeks 48 and 96, respectively. However, in this study, only patients who maintained ADV monotherapy for at least 96 wk were enrolled, which indicates that patients who were good responders to ADV were preferentially selected for the study. Thus, the incidence of ADV resistance in this study does not reflect true genotypic resistance rates among LAM-resistant patients who received ADV monotherapy. We included patients only for those who had received at least 96 wk of ADV monotherapy, because the aim of this study was to determine which patients could continue ADV monotherapy.

In conclusion, the results of this study demonstrate the importance of HBV DNA levels during treatment as an indicator of future ADV resistance. The development of ADV-resistant mutations was closely associated with HBV DNA levels during therapy. The risk of developing ADV-resistant mutations in patients who experienced IVR at week 24 was high. These findings suggest that ADV monotherapy is a viable alternative for LAM-resistant patients with good on-treatment virological response, in areas with limited resources.

A major concern with adefovir (ADV) treatment in lamivudine (LAM)-resistant patients is the selection of ADV-resistant mutations.

Recent studies suggest that combination therapy with ADV and LAM is better than ADV monotherapy in preventing development of ADV resistance among LAM-experienced patients. However cost is of concern, in areas with limited resources.

Recent reports have highlighted the importance of hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA levels during antiviral therapy. On-treatment monitoring strategies are based on the nature of virological response during treatment. This study showed that HBV DNA levels during treatment were also useful in predicting ADV resistance in LAM-resistant patients, thus helps to identify patients that might respond to ADV monotherapy.

This study suggests that ADV monotherapy could be a viable alternative for LAM-resistant patients with good on-treatment virological response to ADV. ADV monotherapy may still be alternative, cost-effective approach especially in areas with limited resources.

Genotypic resistance refers to the detection of mutations that have been shown in in vitro studies to confer resistance to the drug that is being administered. Antiviral-resistant mutations can be detected at months and sometimes years before biochemical breakthrough. Thus, early detection and intervention can prevent hepatitis flares and hepatic decompensation.

This is a retrospective study that evaluated the virological response to ADV monotherapy. This was a good study.

| 1. | Lai CL, Dienstag J, Schiff E, Leung NW, Atkins M, Hunt C, Brown N, Woessner M, Boehme R, Condreay L. Prevalence and clinical correlates of YMDD variants during lamivudine therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis B. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:687-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 490] [Cited by in RCA: 497] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hadziyannis SJ, Tassopoulos NC, Heathcote EJ, Chang TT, Kitis G, Rizzetto M, Marcellin P, Lim SG, Goodman Z, Wulfsohn MS. Adefovir dipivoxil for the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:800-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 780] [Cited by in RCA: 735] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Marcellin P, Chang TT, Lim SG, Tong MJ, Sievert W, Shiffman ML, Jeffers L, Goodman Z, Wulfsohn MS, Xiong S. Adefovir dipivoxil for the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:808-816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1060] [Cited by in RCA: 1020] [Article Influence: 44.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Peters MG, Hann Hw H, Martin P, Heathcote EJ, Buggisch P, Rubin R, Bourliere M, Kowdley K, Trepo C, Gray Df D. Adefovir dipivoxil alone or in combination with lamivudine in patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:91-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 466] [Cited by in RCA: 423] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Perrillo R, Hann HW, Mutimer D, Willems B, Leung N, Lee WM, Moorat A, Gardner S, Woessner M, Bourne E. Adefovir dipivoxil added to ongoing lamivudine in chronic hepatitis B with YMDD mutant hepatitis B virus. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:81-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 329] [Cited by in RCA: 305] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lee YS, Suh DJ, Lim YS, Jung SW, Kim KM, Lee HC, Chung YH, Lee YS, Yoo W, Kim SO. Increased risk of adefovir resistance in patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B after 48 weeks of adefovir dipivoxil monotherapy. Hepatology. 2006;43:1385-1391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rapti I, Dimou E, Mitsoula P, Hadziyannis SJ. Adding-on versus switching-to adefovir therapy in lamivudine-resistant HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2007;45:307-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 269] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fung SK, Chae HB, Fontana RJ, Conjeevaram H, Marrero J, Oberhelman K, Hussain M, Lok AS. Virologic response and resistance to adefovir in patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2006;44:283-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2007;45:507-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1794] [Cited by in RCA: 1778] [Article Influence: 93.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lok AS; EASL. Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;50:227-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1152] [Cited by in RCA: 1156] [Article Influence: 68.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fung J, Lai CL, Tanaka Y, Mizokami M, Yuen J, Wong DK, Yuen MF. The duration of lamivudine therapy for chronic hepatitis B: cessation vs. continuation of treatment after HBeAg seroconversion. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1940-196; quiz 1947. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Choi MS, Yoo BC. Management of chronic hepatitis B with nucleoside or nucleotide analogues: a review of current guidelines. Gut Liver. 2010;4:15-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Keeffe EB, Dieterich DT, Han SH, Jacobson IM, Martin P, Schiff ER, Tobias H. A treatment algorithm for the management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: 2008 update. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1315-141; quiz 1286. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Feld JJ, Heathcote EJ. Hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B: natural history and treatment. Semin Liver Dis. 2006;26:116-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lee JM, Park JY, Kim do Y, Nguyen T, Hong SP, Kim SO, Chon CY, Han KH, Ahn SH. Long-term adefovir dipivoxil monotherapy for up to 5 years in lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Antivir Ther. 2010;15:235-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Keeffe EB, Zeuzem S, Koff RS, Dieterich DT, Esteban-Mur R, Gane EJ, Jacobson IM, Lim SG, Naoumov N, Marcellin P. Report of an international workshop: Roadmap for management of patients receiving oral therapy for chronic hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:890-897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Angus P, Vaughan R, Xiong S, Yang H, Delaney W, Gibbs C, Brosgart C, Colledge D, Edwards R, Ayres A. Resistance to adefovir dipivoxil therapy associated with the selection of a novel mutation in the HBV polymerase. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:292-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 457] [Cited by in RCA: 422] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Villeneuve JP, Durantel D, Durantel S, Westland C, Xiong S, Brosgart CL, Gibbs CS, Parvaz P, Werle B, Trépo C. Selection of a hepatitis B virus strain resistant to adefovir in a liver transplantation patient. J Hepatol. 2003;39:1085-1089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shin JW, Park NH, Jung SW, Park BR, Kim CJ, Jeong ID, Bang SJ, Kim do H. Clinical usefulness of sequential hepatitis B virus DNA measurement (the roadmap concept) during adefovir treatment in lamivudine-resistant patients. Antivir Ther. 2009;14:181-186. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Chen CH, Wang JH, Lee CM, Hung CH, Hu TH, Wang JC, Lu SN, Changchien CS. Virological response and incidence of adefovir resistance in lamivudine-resistant patients treated with adefovir dipivoxil. Antivir Ther. 2006;11:771-778. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Gallego A, Sheldon J, García-Samaniego J, Margall N, Romero M, Hornillos P, Soriano V, Enrĺquez J. Evaluation of initial virological response to adefovir and development of adefovir-resistant mutations in patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Viral Hepat. 2008;15:392-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Peer reviewer: Dr. Assy Nimer, MD, Assistant Professor, Liver Unit, Ziv Medical Centre, BOX 1008, 13100 Safed, Israel

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Zhang DN