Published online Aug 14, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i30.3479

Revised: December 27, 2010

Accepted: January 3, 2011

Published online: August 14, 2011

AIM: To assess the impact of guidelines for albumin prescription in an academic hospital, which is a referral center for liver diseases.

METHODS: Although randomized trials and guidelines support albumin administration for some complications of cirrhosis, the high cost of albumin greatly limits its use in clinical practice. In 2003, a multidisciplinary panel at Sant’Orsola-Malpighi University Hospital (Bologna, Italy) used a literature-based consensus method to list all the acute and chronic conditions for which albumin is indicated as first- or second-line treatment. Indications in hepatology included prevention of post-paracentesis circulatory dysfunction and renal failure induced by spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and treatment of hepatorenal syndrome and refractory ascites. Although still debated, albumin administration in refractory ascites is accepted by the Italian health care system. We analyzed albumin prescription and related costs before and after implementation of the new guidelines.

RESULTS: While albumin consumption and costs doubled from 1998 to 2002, they dropped 20% after 2003, and remained stable for the following 6 years. Complications of cirrhosis, namely refractory ascites and paracentesis, represented the predominant indications, followed by major surgery, shock, enteric diseases, and plasmapheresis. Albumin consumption increased significantly after guideline implementation in the liver units, whereas it declined elsewhere in the hospital. Lastly, extra-protocol albumin prescription was estimated as < 10%.

CONCLUSION: Albumin administration in cirrhosis according to international guidelines does not increase total hospital albumin consumption if its use in settings without evidence of efficacy is avoided.

- Citation: Mirici-Cappa F, Caraceni P, Domenicali M, Gelonesi E, Benazzi B, Zaccherini G, Trevisani F, Puggioli C, Bernardi M. How albumin administration for cirrhosis impacts on hospital albumin consumption and expenditure. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(30): 3479-3486

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i30/3479.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i30.3479

Serum albumin represents approximately 50% of the total plasma protein content in healthy individuals, and generates about 70% of plasma oncotic pressure. The fairly elevated albumin concentration in extracellular fluids and its strong negative charge, which attract sodium, make albumin the main modulator of fluid distribution throughout body compartments. In addition, albumin carries many other biological properties, with implications for drug metabolism, free radical detoxification, inflammatory response, vascular integrity, and coagulation[1,2].

Human albumin is widely employed in clinical practice, but its administration is often inappropriate. This is largely due to a common belief in its efficacy, whereas many indications are still under debate or have been disproved by evidence-based medicine. Indeed, the high cost, the theoretical risk of viral disease transmission, and the availability of cheaper alternatives should be carefully weighed in a cost/effectiveness analysis of albumin prescription. Thus, it is not surprising that several clinical and economic studies have been performed to establish recommendations and guidelines for albumin prescription, but controversy persists[3-9].

At present, it is generally accepted that the administration of non-protein colloids and crystalloids represents the first-line treatment of resuscitation, while the use of albumin in critically ill patients should be reserved for specific conditions[10-15]. Albumin administration is not recommended to correct hypoalbuminemia per se (i.e. not associated with hypovolemia) or for nutritional intervention[6,7,9,16], but this is often disregarded in clinical practice. Albumin is also prescribed in certain conditions and diseases, such as kernicterus, plasmapheresis, and graft-vs-host disease[9], even though these indications are not supported by definite evidence.

Hepatology is a setting where the use of albumin is particularly common, since this treatment is currently employed to treat or prevent severe complications of cirrhosis. Indeed, randomized studies have shown that it is effective in preventing circulatory dysfunction after large-volume paracentesis[17] and renal failure induced by spontaneous bacterial peritonitis[18], and to treat hepatorenal syndrome in association with vasoconstrictors[19-21]. Although the recommendations on the use of albumin in cirrhosis have been endorsed by the International Ascites Club and other international scientific societies[22-26], albumin is not widely administered in clinical practice, even in specialized centers, mainly because of its high cost.

With the aim of rationalizing albumin prescription and reducing health care costs, clinical practice guidelines were devised in 2003, and subsequently implemented at the S Orsola-Malpighi University Hospital in Bologna, Italy, a third-level referral centre for many diseases, including liver cirrhosis and transplantation.

We here report the annual albumin consumption and costs comparing the 5 years before (January 1998-June 2003) with the 6 years after (July 2003-December 2008) implementation of the guidelines. We also analyze the indications for albumin, adherence to the protocol, and the distribution of albumin prescription among specialties in 2008.

In the first half of 2003, clinical practice guidelines for the appropriate prescription of albumin were devised at the Sant’Orsola-Malpighi University Hospital of Bologna, Italy, using a systematic, literature-based consensus method. Briefly, a panel of experts from various disciplines (internal medicine, anesthesia, surgery, gastroenterology, nephrology, hematology, public health, and pharmacy) reviewed the available clinical literature and drew up draft guidelines which were submitted to a second panel of physicians from the same scientific areas, but not involved in the writing of the first draft. Then a consensus was reached by the two working groups and a final version was approved and distributed among the physicians employed at the hospital. Since July 2003, the in-hospital prescription of albumin has been regulated according to the recommendations reported in Table 1. Schematically, they list a series of acute and chronic clinical conditions for which albumin administration is indicated as a first- or second-line treatment or is not indicated at all. The level of scientific evidence and the strength of the recommendation are also reported according to the criteria summarized in Table 2. The guidelines were updated in 2007, but only minor changes were made regarding specific and limited indications.

| Levels of evidence | |

| 1 | Randomized clinical trials and/or meta-analyses |

| 2 | Single randomized clinical trail |

| 3 | Prospective observational studies |

| 4 | Retrospective studies |

| 5 | Cross-sectional surveys and descriptive studies |

| 6 | Opinion of experts in guidelines or consensus |

| Strength of recommendations | |

| A | Strong (levels of evidence 1 and 2) |

| B | Relatively strong (levels of evidence 3, 4 and 5) |

| C | Weak (level of evidence 6) |

| Acute diseases | First-line treatment | Second-line treatment |

| Hypovolemic shock [1, A] | Colloid/crystalloid solutions | Human albumin if: |

| Sodium intake restriction | ||

| Hypersensitivity to colloids or crystalloids | ||

| Lack of response to combined use of colloids and crystalloids | ||

| Major surgery [6, C] | ||

| (1) Cardiovascular surgery | Colloid/crystalloid solutions | Human albumin if: |

| Lack of response to combined use of colloids and crystalloids | ||

| As for hypovolemic shock | ||

| (2) Other surgery | As for hypovolemic shock | |

| Burns [6, C] | Colloid/crystalloid solutions | Human albumin plus crystalloid solutions if: |

| Lack of response to colloid or crystalloid solutions alone | ||

| Severe burns (> 50% body surface) | ||

| Chronic diseases | First-line treatment | Second-line treatment |

| Cirrhosis | Human albumin | |

| (1) Paracentesis [1, A] | 8 g/L of removed ascites if paracentesis > 4 L | |

| (2) Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis [1, A] | 1.5 g/kg at diagnosis and 1 g/kg on third day + antibiotic therapy | |

| (3) Hepatorenal syndrome [1, A] | 1 g/kg at diagnosis followed by 20-40 g/d + vasoconstrictors | |

| (4) Ascites [1, A] | Diuretic treatment | Human albumin if: Ascites resistant to diuretics |

| Plasmapheresis [6, C] | Human albumin if plasma changes > 20 mL/kg per week | |

| Protein wasting enteropathy/malnutrition | Enteral or parenteral nutrition | Human albumin only if: |

| severe diarrhea (> 2 L/d) | ||

| albuminemia < 2 g/dL | ||

| clinical hypovolemia |

Since the protocol was implemented, each order of albumin has been filled in by the prescribing physician using a specific form listing the amount requested, the diagnosis and the indication for albumin use, and the unit of the prescribing physician. All the data regarding in-hospital use of albumin are collected in a database at the hospital pharmacy service and a quarterly report on albumin prescription is sent by mail to all physicians.

Trends of albumin consumption before and after implementation of the clinical practice guidelines were analyzed using the Pearson correlation test. P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using Graph PAD 4.0 software.

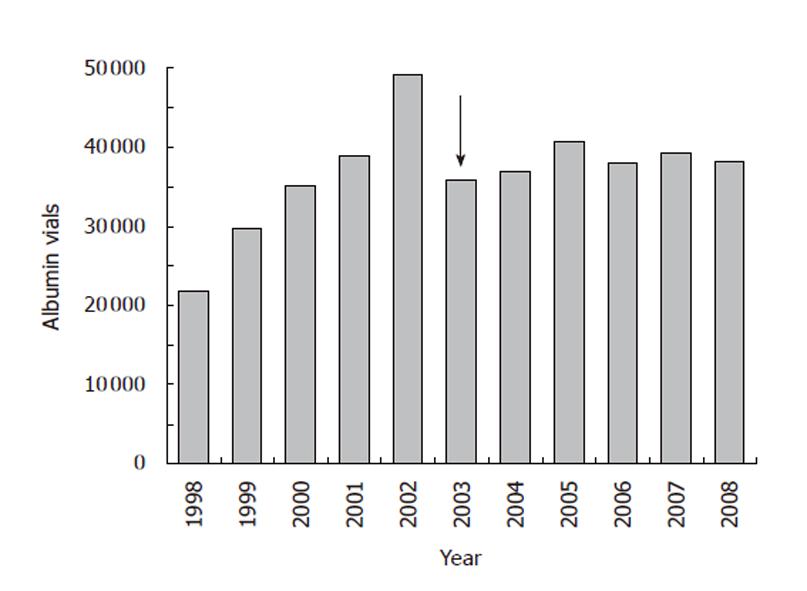

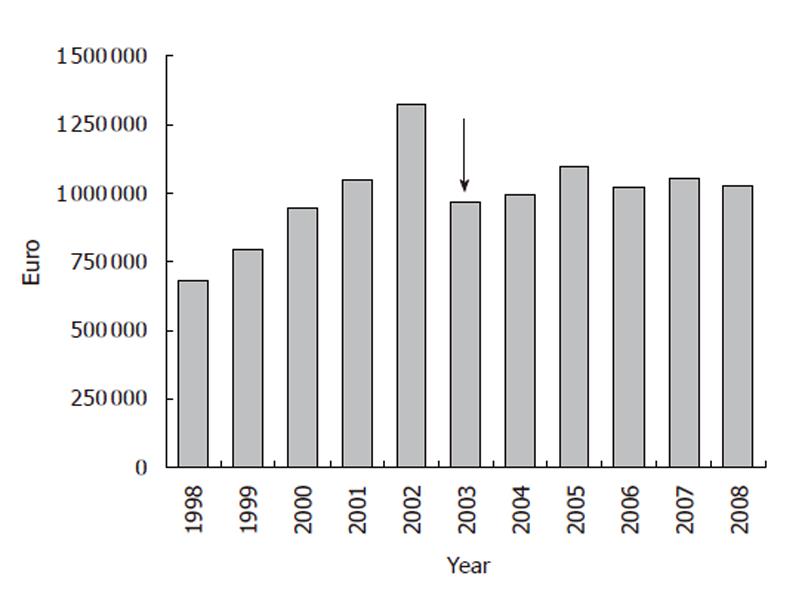

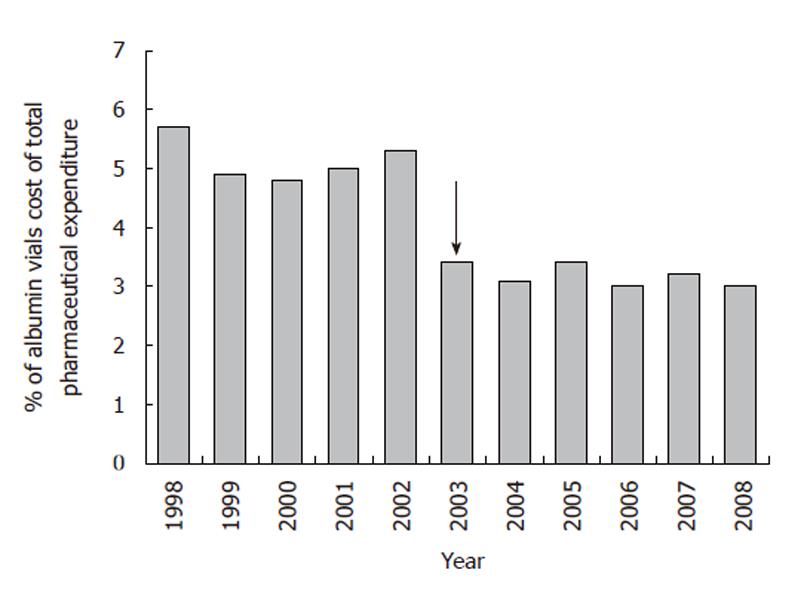

Albumin consumption and costs were monitored at the S Orsola-Malpighi University Hospital from 1998. The number of albumin vials (50 mL containing 10 g albumin, concentration 20%) and the related expenditure more than doubled from 1998 to 2002 (Figures 1, 2). The implementation of recommendations in July 2003 yielded a rapid 15%-20% reduction in albumin use (Figure 1), which was associated with a similar fall in albumin cost both expressed in absolute terms (Figure 2) or as percentage of the global pharmaceutical expenditure (Figure 3). Thereafter, albumin consumption and related costs remained substantially stable during the following 6 years (Figures 1-3). The data for the 2003 represent the sum of two periods with different prescription modalities (before and after guidelines implementation). The cost of each albumin vial paid for by our hospital remained stable throughout the study period.

Finally, as shown in Figure 4, the trend analysis of albumin consumption clearly indicates that its time-dependent increase was interrupted by the implementation of the recommendations, supporting their efficacy in regulating in-hospital albumin prescription.

As the annual breakdown of albumin prescriptions among the major indications did not change significantly in the period 2003-2008, we present only the prescription analysis performed on the data for 2008 (Figure 4). Complications of cirrhosis represent the predominant indication for albumin use, accounting for 52% of vials utilized and 36% of patients treated. Major surgery was the second commonest indication for albumin use. Taking into account that liver transplantation and hepatic resection constitute approximately 30% of these surgical cases, it is evident that liver diseases represent the setting where the majority of albumin was prescribed. Other relatively common indications were shock not responsive to crystalloid/colloids in intensive care units (ICUs), bowel diseases associated with malnutrition, and plasmapheresis (Table 3).

| Vials (number)(%) | Cost (euros) | Patients (number)(%) | Vials/patients (number) | Cost/patient (euros) | |

| Cirrhosis | 19 871 (52) | 534.532 | 807 (36.3) | 24.6 | 662 |

| Major surgery | 6196 (16.2) | 166.982 | 495 (22.2) | 12.5 | 337 |

| Shock | 5069 (13.3) | 136.558 | 447 (20) | 11.3 | 305 |

| Enteric disease | 2982 (7.8) | 80.215 | 146 (6.5) | 20.4 | 549 |

| Plasmapheresis | 2333 (6.1) | 62.757 | 54 (2.4) | 43.2 | 1162 |

| Mars | 196 (0.5) | 5.272 | 6 (0.2) | 32.6 | 878 |

| Others1 | 201 (0.5) | 5353.000 | 149 (6.7) | 7.1 | 260 |

| Extra-protocol | 1240 (3.7) | 33.418 | 119 (5.3) | 10.5 | 281 |

The mean number of albumin vials per patient and the related cost were higher in patients with cirrhosis than in those presenting other indications, with the two expected exceptions being plasmapheresis and albumin dialysis with the molecular adsorbent recirculating system (MARS) (Table 3). Finally, the use of albumin outside protocol indications occurred only in about 10% of cases and mainly in patients with edematous and/or anasarcatic states (Table 3).

Ascites not responding to diuretic treatment represented the major indication for albumin prescription in patients with liver cirrhosis, and the high number of albumin vials per patient likely reflected the prolonged length of treatment. Repeated procedures also resulted in increased albumin consumption in patients after large-volume paracentesis to prevent post-paracentesis circulatory dysfunction (Table 4).

| Vials (number)(%) | Cost (euros) | Patients (number)(%) | Vials/patients (number) | Cost/patient (euros) | |

| Ascites | 12.540 (63.3) | 337.976 | 453 (56.4) | 27.7 | 746 |

| Paracentesis | 4.564 (23.1) | 122.988 | 222 (27.6) | 20.6 | 554 |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | 2.340 (11.8) | 63.070 | 106 (13.2) | 22.0 | 595 |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 367.000 (1.8) | 9.880 | 22 (2.7) | 14.0 | 380 |

Although it appears that hypoalbuminemia was the major indication before guideline implementation (data not shown), we could not perform an accurate comparison between the two 5-year periods of prescription since the data were not systematically collected before 2003. In an attempt to overcome this limitation of the study, we analyzed albumin consumption after grouping all the units into three main categories: hepatological medical and surgical units, i.e. units representing referral centers for liver diseases, non-hepatological medical and surgical units, and ICUs. While the proportion of albumin consumption remained stable over the years in the ICU, the increase observed in the “hepatological” units after guideline implementation was mirrored by a parallel decrease in the “non-hepatological” units (Figure 5).

Albumin utilization remains highly controversial in a variety of clinical settings in terms of indications, efficacy, and cost-benefit ratio. Over the last 10-15 years, specific conditions for which albumin administration is indicated have been defined, and liver disease possibly represents a field where this has been most clearly and convincingly demonstrated. However, besides inappropriate prescribing, the high cost of albumin infusion is the main issue leading health authorities and hospital administrators to restrict its use, and this has often prevented the widespread application of indications emerging from international guidelines in hepatology.

The present study clearly shows that in a general hos-pital the recommendations for the use of albumin in patients with cirrhosis can be followed without increasing the global pharmaceutical costs, despite the large amounts of albumin required. This can be achieved by implementing rational albumin prescription guidelines, thereby avoiding its futile administration in settings where there is a lack of clinical evidence of efficacy. The clinical practice guidelines devised by our hospital to regulate albumin prescription used a literature-based consensus method and adopted all the recognized indications for albumin administration in hepatology, such as prevention of post-paracentesis circulatory dysfunction, prevention of renal impairment in patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and treatment of hepatorenal syndrome in association with vasoconstrictors. These guidelines managed to curb the incremental trend of albumin consumption and related costs recorded in previous years. In our view, these results are particularly important given the characteristics of our hospital, that acts both as an academic third-level and primary referral centre, hosts a program for liver transplantation, and where several medical and surgical units are devoted to the management of chronic liver diseases. Not surprisingly, the prevention or treatment of complications of cirrhosis was the commonest reason for prescribing albumin in our institution, and albumin use in this setting increased after our in-hospital clinical practice guidelines were implemented.

Refractory ascites was the most common specific indication for albumin infusion, and the high number of vials given to each patient likely reflects the need for sustained albumin administration in these cases. This finding merits some comment as the use of albumin to treat cirrhotic ascites is controversial with a lack of clear evidence in its favor. Despite this debate, the Italian Drug Agency (AIFA) permits albumin reimbursement by the National Health Service in patients with refractory ascites based on the results of two Italian studies[27,28]. First, the Albumin Delphi Study, designed to gain a consensus among Italian physicians, showed that 80% of hepatologists agree that albumin treatment shortens the length of hospitalization, enhances the response to diuretics, lowers the relapse rate of ascites when given at home, and also improves patient general condition and well-being[26]. Second, a controlled clinical trial in 126 patients with decompensated cirrhosis reported that treatment with diuretics plus albumin favored the disappearance of ascites, shortened the hospital stay, and reduced the rate of ascites recurrence and readmission to hospital due to ascites compared with diuretics alone[27]. More recently, the same research group showed that long-term albumin administration increased patient survival and reduced the risk of ascites recurrence in patients with first-onset ascites followed for a median of 7 years[28]. No other controlled clinical trials have so far been performed to evaluate the effectiveness of prolonged albumin administration in the treatment of cirrhotic ascites. Thus, the lack of confirmatory multicenter randomized studies together with the high cost of albumin infusion explains why albumin is not usually included among the therapeutic options for difficult-to-treat ascites in countries other than Italy. For instance, the most recent international guidelines for the management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis[25,29] do not even mention albumin as a possible therapeutic tool for either responsive or refractory ascites.

In the last 15 years, large randomized trials and meta-analyses have focused on the use of human albumin in the setting of critically ill patients, the clinical field where international guidelines for albumin prescription were first established. These studies showed that beside being cheaper, non-protein colloids and crystalloids are equally or even more effective than albumin for fluid resuscitation and blood volume expansion in patients with hypovolemic shock and critical illnesses, representing the first-line treatment in these cases. Thus, albumin should only be administered in the presence of contraindications to the use of colloids and/or crystalloids or specific conditions, such as the need for salt intake restriction[10-15]. Interestingly, the implementation of our in-hospital guidelines has not produced significant changes in albumin prescription by physicians working in ICUs, probably because they were already accustomed to established international guidelines, despite the ongoing dispute on the matter.

As global albumin consumption at our hospital declined by 15%-20%, the greatest saving occurred in non-hepatological medical and surgical units where hypoalbuminemia per se was probably the main reason for prescribing albumin before implementation of our in-hospital guidelines, despite the lack of scientific evidence supporting albumin administration to correct plasma albumin concentration and/or improve nutritional status[6,7,9,16].

Our hospital guidelines, like other local recommendations[3-9], also authorize albumin prescribing for specific procedures and clinical situations. These niche indications differ among guidelines and reflect the particular settings of highly specialized centers, such as university hospitals. Although these indications only affect a small number of patients, the albumin consumption per patient can be very high, as in the MARS procedure[30], or the treatment of orphan diseases, such as intestinal lymphangiectasia.

Several aspects of our study must be addressed for a correct evaluation of the results. The recommendations for albumin prescription in our hospital were devised using a systematic, literature-based consensus method, but not all of them were supported by solid scientific evidence derived from large randomized clinical trials, meta-analyses of trials or universally accepted guidelines. Despite this limitation, implementation of the protocol clearly interrupted the incremental trend in albumin consumption and related expenditure seen in previous years. Of course, most physicians must strictly adhere to the guidelines in order to control and, possibly, curb albumin consumption. Several ad hoc strategies were adopted: (1) involvement of experts from many disciplines in drafting the consensus document; (2) use of an albumin order form restating the recommendations at the time of prescription, a measure known to enhance compliance[31]; and (3) regular information sent to every physician in a quarterly report on in-hospital albumin prescription. Such a policy achieved a formal adherence to the protocol in approximately 85% of prescriptions. This figure, however, relied on the assumption that data reported on the order form correctly describe the patient’s clinical status, because this concordance was not monitored on a regular basis. Finally, our study cannot provide any information on the impact of the recommendations on the patients’ clinical outcomes and global hospital costs. This was beyond the scope of the present analysis and can only be determined by prospective studies designed to assess the cost/benefit ratio of albumin treatment for each specific disease.

In conclusion, this study indicates that prescribing albumin according to the current guidelines in hepatology does not increase total albumin consumption or costs in a hospital acting as both an academic third-level and primary referral center. This result can be achieved provided that albumin prescription is strictly regulated by practical recommendations designed to avoid ineffective albumin infusion in settings without scientific evidence of efficacy. The present data may promote the appropriateness of albumin prescription, particularly in clinical settings where the use of albumin is dogmatically limited rather than regulated on the basis of current scientific evidence. In this sense, our results may foster the acceptance of internationally endorsed indications for the use of albumin in hepatology by health authorities and hospital administrations.

Human albumin is widely employed in clinical practice, but its administration is often inappropriate. This is largely due to a common belief in its efficacy, whereas many indications are still under debate or have been disproved by evidence-based medicine. In the field of hepatology, albumin is currently used to treat or prevent severe complications of cirrhosis. Although the recommendations on the use of albumin in cirrhosis have been endorsed by the International Ascites Club and other international scientific societies, albumin is not widely administered in clinical practice, even in specialized centers, mainly because of its high cost.

As albumin utilization remains highly controversial in a variety of clinical settings in terms of indications, efficacy, and cost-benefit ratio, the implementation of practical recommendations and guidelines, based on solid scientific evidence, appears to be a necessary step to rationalize the use of this expensive hemoderivate.

The present study clearly showed that in an academic general hospital, the adherence to the international scientific guidelines for the use of albumin in patients with cirrhosis does not increase the global pharmaceutical costs, despite the large amounts of albumin required. This can be achieved by implementing rational albumin prescription guidelines, thereby avoiding its futile administration in settings that lack scientific evidence of efficacy.

The present data may promote the appropriateness of albumin prescription, particularly in clinical settings where the use of albumin is limited rather than regulated on the basis of current scientific evidence. The results may foster the acceptance of internationally endorsed indications for the use of albumin in hepatology by health authorities and hospital administrations. However, this study suffers an important limitation as the effects of the recommendations on the patients’ clinical outcomes and global hospital costs could not be determined in the present investigation and only prospective studies specifically designed for this purpose will be able to provide the real cost-effectiveness of treatment for each specific disease.

This study shed more light on the continued dilemma of consumption and costs of albumin administration particularly in patients with liver disease.

| 1. | Evans TW. Review article: albumin as a drug--biological effects of albumin unrelated to oncotic pressure. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16 Suppl 5:6-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 280] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Quinlan GJ, Martin GS, Evans TW. Albumin: biochemical properties and therapeutic potential. Hepatology. 2005;41:1211-1219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 600] [Cited by in RCA: 668] [Article Influence: 31.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Favaretti C, Selle V, Marcolongo A, Orsini A. The appropriateness of human albumin use in the hospital of Padova, Italy. Qual Assur Health Care. 1993;5:49-55. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Vermeulen LC, Ratko TA, Erstad BL, Brecher ME, Matuszewski KA. A paradigm for consensus. The University Hospital Consortium guidelines for the use of albumin, nonprotein colloid, and crystalloid solutions. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:373-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Vargas E, de Miguel V, Portolés A, Avendaño C, Ambit MI, Torralba A, Moreno A. Use of albumin in two Spanish university hospitals. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;52:465-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Debrix I, Combeau D, Stephan F, Benomar A, Becker A. Clinical practice guidelines for the use of albumin: results of a drug use evaluation in a Paris hospital. Tenon Hospital Paris. Pharm World Sci. 1999;21:11-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tarín Remohí MJ, Sánchez Arcos A, Santos Ramos B, Bautista Paloma J, Guerrero Aznar MD. Costs related to inappropriate use of albumin in Spain. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:1198-1205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tanzi M, Gardner M, Megellas M, Lucio S, Restino M. Evaluation of the appropriate use of albumin in adult and pediatric patients. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2003;60:1330-1335. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Pradel V, Tardieu S, Micallef J, Signoret A, Villano P, Gauthier L, Vanelle P, Blin O. Use of albumin in three French university hospitals: is prescription monitoring still useful in 2004? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16:79-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cochrane Injuries Group Albumin Reviewers. Human albumin administration in critically ill patients: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 1998;317:235-240. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Wilkes MM, Navickis RJ. Patient survival after human albumin administration. A meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:149-164. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Alderson P, Bunn F, Lefebvre C, Li WP, Li L, Roberts I, Schierhout G. Human albumin solution for resuscitation and volume expansion in critically ill patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;CD001208. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Vincent JL, Navickis RJ, Wilkes MM. Morbidity in hospitalized patients receiving human albumin: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:2029-2038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Finfer S, Bellomo R, Boyce N, French J, Myburgh J, Norton R. A comparison of albumin and saline for fluid resuscitation in the intensive care unit. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2247-2256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1885] [Cited by in RCA: 1581] [Article Influence: 71.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Vincent JL. Relevance of albumin in modern critical care medicine. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2009;23:183-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Fan C, Phillips K, Selin S. Serum albumin: new thoughts of an old treatment. BC Med J. 2005;47:438-444. |

| 17. | Ginès A, Fernández-Esparrach G, Monescillo A, Vila C, Domènech E, Abecasis R, Angeli P, Ruiz-Del-Arbol L, Planas R, Solà R. Randomized trial comparing albumin, dextran 70, and polygeline in cirrhotic patients with ascites treated by paracentesis. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1002-1010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 392] [Cited by in RCA: 353] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Sort P, Navasa M, Arroyo V, Aldeguer X, Planas R, Ruiz-del-Arbol L, Castells L, Vargas V, Soriano G, Guevara M. Effect of intravenous albumin on renal impairment and mortality in patients with cirrhosis and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:403-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1132] [Cited by in RCA: 1007] [Article Influence: 37.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 19. | Angeli P, Volpin R, Gerunda G, Craighero R, Roner P, Merenda R, Amodio P, Sticca A, Caregaro L, Maffei-Faccioli A. Reversal of type 1 hepatorenal syndrome with the administration of midodrine and octreotide. Hepatology. 1999;29:1690-1697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 383] [Cited by in RCA: 327] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Martín-Llahí M, Pépin MN, Guevara M, Díaz F, Torre A, Monescillo A, Soriano G, Terra C, Fábrega E, Arroyo V. Terlipressin and albumin vs albumin in patients with cirrhosis and hepatorenal syndrome: a randomized study. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1352-1359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 415] [Cited by in RCA: 407] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Sanyal AJ, Boyer T, Garcia-Tsao G, Regenstein F, Rossaro L, Appenrodt B, Blei A, Gülberg V, Sigal S, Teuber P. A randomized, prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of terlipressin for type 1 hepatorenal syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1360-1368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 446] [Cited by in RCA: 452] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rimola A, García-Tsao G, Navasa M, Piddock LJ, Planas R, Bernard B, Inadomi JM. Diagnosis, treatment and prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a consensus document. International Ascites Club. J Hepatol. 2000;32:142-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 650] [Cited by in RCA: 615] [Article Influence: 23.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wong F, Bernardi M, Balk R, Christman B, Moreau R, Garcia-Tsao G, Patch D, Soriano G, Hoefs J, Navasa M. Sepsis in cirrhosis: report on the 7th meeting of the International Ascites Club. Gut. 2005;54:718-725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 279] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Salerno F, Gerbes A, Ginès P, Wong F, Arroyo V. Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. Gut. 2007;56:1310-1318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 363] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Salerno F; EASL. Clinical practice guidelines on the management of ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. Available from: http://www.easl.ch. |

| 26. | Gentilini P, Bernardi M, Bolondi L, Craxi A, Gasbarrinie G, Ideo G, Laffi G, La Villa G, Salerno F, Ventura E. The rational use of albumin in patients with cirrhosis and ascites. A Delphi study for the attainment of a consensus on prescribing standards. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36:539-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Gentilini P, Casini-Raggi V, Di Fiore G, Romanelli RG, Buzzelli G, Pinzani M, La Villa G, Laffi G. Albumin improves the response to diuretics in patients with cirrhosis and ascites: results of a randomized, controlled trial. J Hepatol. 1999;30:639-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Romanelli RG, La Villa G, Barletta G, Vizzutti F, Lanini F, Arena U, Boddi V, Tarquini R, Pantaleo P, Gentilini P. Long-term albumin infusion improves survival in patients with cirrhosis and ascites: an unblinded randomized trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1403-1407. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Runyon BA. Management of adult patients with ascites due to cirrhosis: an update. Hepatology. 2009;49:2087-2107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 628] [Cited by in RCA: 626] [Article Influence: 36.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Karvellas CJ, Gibney N, Kutsogiannis D, Wendon J, Bain VG. Bench-to-bedside review: current evidence for extracorporeal albumin dialysis systems in liver failure. Crit Care. 2007;11:215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Grimshaw JM, Russell IT. Effect of clinical guidelines on medical practice: a systematic review of rigorous evaluations. Lancet. 1993;342:1317-1322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1843] [Cited by in RCA: 1720] [Article Influence: 52.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Peer reviewer: Hussein M Atta, MD, PhD, Department of Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Minia University, Mir-Aswan Road, 61519 El-Minia, Egypt

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Ma WH