Published online Jun 21, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i23.2867

Revised: January 11, 2011

Accepted: January 18, 2011

Published online: June 21, 2011

AIM: To investigate the efficiency of Cox proportional hazard model in detecting prognostic factors for gastric cancer.

METHODS: We used the log-normal regression model to evaluate prognostic factors in gastric cancer and compared it with the Cox model. Three thousand and eighteen gastric cancer patients who received a gastrectomy between 1980 and 2004 were retrospectively evaluated. Clinic-pathological factors were included in a log-normal model as well as Cox model. The akaike information criterion (AIC) was employed to compare the efficiency of both models. Univariate analysis indicated that age at diagnosis, past history, cancer location, distant metastasis status, surgical curative degree, combined other organ resection, Borrmann type, Lauren’s classification, pT stage, total dissected nodes and pN stage were prognostic factors in both log-normal and Cox models.

RESULTS: In the final multivariate model, age at diagnosis, past history, surgical curative degree, Borrmann type, Lauren’s classification, pT stage, and pN stage were significant prognostic factors in both log-normal and Cox models. However, cancer location, distant metastasis status, and histology types were found to be significant prognostic factors in log-normal results alone. According to AIC, the log-normal model performed better than the Cox proportional hazard model (AIC value: 2534.72 vs 1693.56).

CONCLUSION: It is suggested that the log-normal regression model can be a useful statistical model to evaluate prognostic factors instead of the Cox proportional hazard model.

- Citation: Wang BB, Liu CG, Lu P, Latengbaolide A, Lu Y. Log-normal censored regression model detecting prognostic factors in gastric cancer: A study of 3018 cases. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(23): 2867-2872

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i23/2867.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i23.2867

The survival of patients with gastric cancer has recently been improved because of early detection, rational lymphadenectomy and several therapeutic modalities[1,2]. However, gastric cancer still remains the second leading cause of cancer mortality in the world. It is acknowledged that surgery and systemic chemotherapy can clearly improve the survival of patients with gastric cancer[3,4]. However, a sensible treatment option must be fundamentally based on the current evaluation of prognostic factors, so a rational method to evaluate the prognostic factors is very important in establishing therapeutic strategies and evaluate prognosis.

Survival analysis is a branch of statistics which deals with death in biological organisms and failure in mechanical systems. The Cox model is the standard tool for assessing the effect of prognostic factors; however, there may be substantive differences in the estimated prognosis obtained by the Cox model rather than a log-normal model[5]. The Cox model is semiparametric, in that the baseline hazard takes on no particular form[6]. In contrast to Cox, a link to parametric survival models comes through alternative functions for the baseline hazard. In this case, one can let the baseline hazard be a parametric form such as log-normal. It is acknowledged that most of studies used the Cox proportional hazard model to find the relation between survival time and covariates of patients with gastric cancer[7-9]. On the other hand, some studies reported that log-normal regression could estimate the parameter more efficiently than the Cox model[5]. However, the efficiency of log-normal regression was still controversial.

The aim of this retrospective study was to elucidate the factors affecting the survival of patients with GC using log-normal regression, and to compare these results with the Cox model.

In this study, three thousand and eighteen cases with gastric cancer were selected on whom an operation was performed at the China Medical University between 1980 and 2004. The selection criteria for inclusion were as follows: (1) an operation was performed; (2) lymph nodes were dissected and then pathologically examined; and (3) the patient medical records were available. All patients were periodically followed up through post letters, and/or telephone interviews with patients and their relatives. Clinical, surgical and pathological findings, and all follow-up information were collected and recorded in a database, and 5-year survival rate was calculated. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of China Medical University.

Lymph nodes were meticulously dissected from the en bloc specimens, and the classification of the dissected lymph nodes was determined by surgeons who reviewed the excised specimens after surgery based on the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma[10]. Accordingly, lymphadenectomy was classified as D1, dissection of all the Group 1 lymph nodes; D2, dissection of all Group 1 and Group 2 lymph nodes; and D3, dissection of all the Group 1, Group 2 and Group 3 lymph nodes. pN category was defined as pN0 (no metastatic lymph node), pN1 (1-6 metastatic lymph nodes), pN2 (7-15 metastatic lymph nodes) and pN3 (> 15 metastatic lymph nodes), according to the 5th Edition of UICC[11]. The location of tumors was defined as upper, middle and lower third gastric cancer, according to JCGC[10] and the histological grade was defined as poorly differentiated, moderately differentiated and well differentiated, according to the latest World Health Organization (WHO) classification[12]. The Borrmann type was defined as Borrmann I, Borrmann II, Borrmann III and Borrmann IV, according to JCGC[10]. The histological type was determined according to Lauren’s classification.

All data were analyzed using STAT statistics software (Version 10.0, Stata Corp LP). Clinic-pathologic factors were entered to a log-normal censored regression, as well as a Cox proportional hazard model in univariate and multivariate analysis in order to find the prognostic factors. The term of relative risk (RR) was used to interpret the risk of death in parametric results and the term of Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was employed to compare the efficiency of models. Disease-specific survival was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used to analyze survival differences. Lower AIC indicates better likelihood. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The male-to-female ratio among the 3018 patients enrolled was 2.74:1 and the mean age was 57.54 years (range: 19 to 90 years) at operation. 269, 1362 and 608 cases received D1, D2 and more than D2 lymph node dissection respectively. In addition, six hundred and fifty seven cases received palliative surgery. From 3018 cases, a total of 46081 lymph nodes were removed and examined, and the mean number of examined lymph nodes was 15.27. One thousand six hundred and forty three cases were observed lymph node metastasis. Thus, the incidence of lymph node metastasis was 54.44%. The last follow-up was Jan 1, 2009, with a total follow-up rate of 70.68%. More clinic-pathologic factors are shown in Table 1.

| Variable | Subgroups | Frequency |

| Gender ratio | Male | 2211 (73.26) |

| Female | 807 (26.74) | |

| Age at diagnosis (mean ± SD; yr) | 57.54 ± 11.24 | |

| Past history | ||

| Without | 2234 (74.02) | |

| With | 784 (25.98) | |

| Family history | Without | 2467 (81.74) |

| With | 551 (18.26) | |

| Cancer number | Single | 2883 (96.65) |

| Multiple | 100 (3.35) | |

| Cancer location | Lower stomach | 1873 (62.64) |

| Middle stomach | 492 (16.46) | |

| Upper stomach | 355 (11.87) | |

| Total stomach | 270 (9.03) | |

| Distant metastasis status | Without | 2540 (85.04) |

| With | 447 (14.96) | |

| Maximum tumor diameter (mean ± SD, cm) | 5.85 ± 3.30 | |

| Surgical curative degree | Absolutely radical | 1396 (49.73) |

| Relatively radical | 809 (28.82) | |

| Palliative | 602 (21.45) | |

| Lymph node dissection | More than D2 | 608 (20.99) |

| D2 | 1362 (47.03) | |

| D1 | 269 (9.29) | |

| Palliative surgery | 657 (22.69) | |

| Combined other organ resection | Without | 2016 (76.80) |

| With | 609 (23.20) | |

| Histological type | Well differentiated | 755 (27.43) |

| Middle differentiated | 382 (13.88) | |

| Poor differentiated | 1615 (58.69) | |

| Borrmann classification | I | 70 (2.98) |

| II | 426 (18.15) | |

| III | 1571 (66.94) | |

| IV | 280 (11.93) | |

| Lauren classification | Intestinal type | 1170 (43.89) |

| Diffuse type | 1496 (56.11) | |

| pT stage | pT1 | 328 (11.89) |

| pT2 | 1486 (53.88) | |

| pT3 | 737 (26.72) | |

| pT4 | 207 (7.51) | |

| Total dissected lymph node (mean ± SD) | 15.27 ± 13.11 | |

| Pathological lymph node status | pN0 | 1375 (45.56) |

| pN1 | 1039 (34.43) | |

| pN2 | 432 (14.31) | |

| pN3 | 172 (5.70) |

Univariate analysis indicated that age at diagnosis, past history, cancer location, distant metastasis status, surgical curative degree, combined other organ resection, Borrmann type, Lauren’s classification, pT stage, total dissected nodes and pN stage were prognostic factors in both log-normal and Cox models. In the final multivariate model, age at diagnosis, past history, surgical curative degree, Borrmann type, Lauren’s classification pT stage, and pN stage were significant prognostic factors in both log-normal and Cox models. However, cancer location, distant metastasis status and histology types were found as significant prognostic factors in log-normal results alone (Table 2). According to AIC, the log-normal model performed better than the Cox proportional hazard model (AIC value: 2534.72 vs 1693.56) (Table 3).

| HR (95% CI) | ||||

| Cox | Log normal | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 0.953 (0.843-1.078) | 0.925 (0.818-1.046) | ||

| Female | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Age at diagnosis | 1.0151 (1.009-1.020) | 1.0161 (1.011-1.021) | ||

| Past history | ||||

| Without | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| With | 0.7151 (0.631-0.831) | 0.6941 (0.612-0.787) | ||

| Family history | ||||

| Without | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| With | 0.871 (0.752-1.009) | 0.875 (0.754-1.014) | ||

| Cancer number | ||||

| Single | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Multiple | 0.870 (0.622-1.218) | 0.924 (0.661-1.294) | ||

| Cancer location | ||||

| Lower third | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Middle third | 1.1811 (1.017-1.373) | 1.3021 (1.233-1.374) | ||

| Upper third | 1.4361 (1.212-1.701) | 1.6951 (1.429-1.897) | ||

| Total stomach | 2.4641 (2.062-2.944) | 2.2071 (2.011-2.677) | ||

| Distant metastasis | ||||

| Absent | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Present | 2.5541 (2.194-2.973) | 2.5961 (2.227-3.027) | ||

| Surgical curative degree | ||||

| Absolutely radical | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Relatively radical | 1.8351 (1.593-2.114) | 2.1591 (2.020-2.308) | ||

| Palliative | 4.2361 (3.714-4.832) | 4.6611 (4.214-4.759) | ||

| Lymph node dissection | ||||

| > D2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| D2 | 0.989 (0.859-1.138) | 1.5361 (1.458-1.619) | ||

| D1 | 1.056 (0.853-1.307) | 2.3591 (2.121-2.574) | ||

| < D1 | 3.3101 (2.854-3.839) | 3.6241 (3.231-3.862) | ||

| Combined other organ resection | ||||

| Without | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| With | 1.9811 (1.749-2.245) | 2.0701 (1.825-2.348) | ||

| Histologic types | ||||

| Well differentiated | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Middle differentiated | 0.7061 (0.592-0.843) | 0.976 (0.918-1.039) | ||

| Poor differentiated | 0.918 (0.814-1.036) | 0.952 (0.897-1.011) | ||

| Borrmann classification (n (%)) | ||||

| I | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| II | 1.005 (0.892-1.340) | 0.981 (0.894-1.019) | ||

| III | 1.2471 (1.173-1.638) | 1.1761 (1.074-1.293) | ||

| IV | 2.5121 (1.842-3.075) | 2.6101 (2.416-3.153) | ||

| Lauren classification (n (%)) | ||||

| Intestinal type | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Diffuse type | 1.2451 (1.082-1.184) | 1.1711 (1.015-1.384) | ||

| pT stage | ||||

| pT1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| pT2 | 2.9361 (2.299-3.751) | 1.7871 (1.666-1.916) | ||

| pT3 | 4.3051 (3.357-5.522) | 3.1931 (3.066-3.321) | ||

| pT4 | 7.6971 (5.759-10.287) | 5.7071 (5.579-5.833) | ||

| Total dissected nodes | 0.9931 (0.988-0.998) | 0.9941 (0.988-0.998) | ||

| pN stage | ||||

| pN0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| pN1 | 1.5551 (1.372-1.764) | 1.6331 (1.533-1.740) | ||

| pN2 | 2.5101 (2.133-2.953) | 2.6671 (2.561-2.772) | ||

| pN3 | 3.6691 (2.901-4.640) | 4.3551 (4.249-4.460) | ||

| Cox HR (95% CI) | Log normal HR (95% CI) | |||

| Full model (AIC = 1508.49) | Final model (AIC = 2534.72) | Full model (AIC = 913.34) | Final model (AIC = 1693.56) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 0.91 (0.801-1.034) | 0.886 (0.781-1.005) | ||

| Female | 1.00 | |||

| Age at diagnosis | 1.0141 (1.009-1.02) | 1.0111 (1.006-1.017) | 1.0151 (1.010-1.021) | 1.0151 (1.009-1.020) |

| Past history | ||||

| Without | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| With | 0.8401 (0.738-0.955) | 0.8581 (0.755-0.975) | 0.8131 (0.716-0.914) | 0.8091 (0.713-0.919) |

| Family history | ||||

| Without | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| With | 0.957 (0.8254-1.11) | 0.967 (0.833-1.234) | ||

| Cancer number | ||||

| Single | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Multiple | 1.21 (0.861-1.701) | 1.312 (1.935-1.840) | ||

| Cancer location | ||||

| Lower third | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Middle third | 1.033 (0.885-1.205) | 1.1351 (1.073-1.199) | 1.1291 (1.069-1.194) | |

| Upper third | 1.4061 (1.173-1.686) | 1.2881 (1.224-1.353) | 1.2771 (1.211-1.338) | |

| Total stomach | 1.4661 (1.214-1.771) | 1.4621 (1.365-1.558) | 1.4391 (1.343-1.535) | |

| Distant metastasis | ||||

| Absent | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Present | 1.211 (1.013-1.447) | 1.2051 (1.011-1.437) | 1.1981 (1.009-1.424) | |

| Surgical curative degree | ||||

| Absolutely radical | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Relatively radical | 1.3891 (1.197-1.611) | 1.3831 (1.194-1.601) | 1.7241 (1.537-1.934) | 1.6721 (1.538-1.817) |

| Palliative | 3.8891 (2.583-5.855) | 2.6871 (2.316-3.116) | 2.9721 (2.770-3.174) | 2.7961 (2.653-2.938) |

| Lymph node dissection | ||||

| > D2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| D2 | 0.908 (0.784-1.051) | 0.967 (0.892-1.049) | ||

| D1 | 0.901 (0.712-1.14) | 0.935 (0.855-1.015) | ||

| < D1 | 0.6071 (0.395-0.935) | 0.904 (0.784-1.024) | ||

| Combined other organ resection | ||||

| Without | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| With | 1.4061 (1.227-1.61) | 1.4471 (1.264-1.657) | ||

| Histologic types | ||||

| Well differentiated | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Middle differentiated | 1.056 (0.878-1.271) | 1.1101 (1.042-1.183) | 1.1201 (1.051-1.193) | |

| Poor differentiated | 1.1791 (1.035-1.343) | 1.2321 (1.160-1.304) | 1.2541 (1.182-1.327) | |

| Borrmann classification | ||||

| I | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| II | 1.142 (0.957-1.319) | 1.201 (1.068-1.433) | 1.018 (0.943-1.106) | 1.015 (0.941-1.102) |

| III | 1.3151 (1.113-1.672) | 1.3941 (1.205-1.741) | 1.2461 (1.052-1.539) | 1.2411 (1.047-1.533) |

| IV | 2.1261 (1.758-3.119) | 2.2531 (1.827-3.284) | 2.5301 (2.376-2.713) | 2.5261 (2.372-2.708) |

| Lauren classification | ||||

| Intestinal type | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Diffuse type | 1.1311 (1.012-1.358) | 1.3071 (1.154-1.528) | 1.3021 (1.148-1.523) | |

| pT stage | ||||

| pT1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| pT2 | 1.8511 (1.431-2.394) | 1.9711 (1.528-2.542) | 1.1951 (1.102-1.297) | 1.1931 (1.100-1.294) |

| pT3 | 1.9811 (1.511-2.598) | 2.191 (1.678-2.858) | 1.4281 (1.328-1.527) | 1.4231 (1.324-1.522) |

| pT4 | 2.3441 (1.699-3.235) | 2.5011 (1.821-3.435) | 1.7061 (1.557-1.855) | 1.6971 (1.549-1.847) |

| Total dissected nodes | 0.9871 (0.981-0.993) | 0.9881 (0.982-0.993) | ||

| pN stage | ||||

| pN0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| pN1 | 1.2811 (1.123-1.461) | 1.2661 (1.11-1.444) | 1.5071 (1.393-1.620) | 1.5001 (1.387-1.622) |

| pN2 | 2.1391 (1.783-2.566) | 2.0951 (1.749-2.51) | 2.2711 (2.151-2.391) | 2.2501 (2.130-2.370) |

| pN3 | 3.241 (2.446-4.292) | 3.3251 (2.52-4.386) | 3.4221 (3.242-3.602) | 3.3751 (3.196-3.554) |

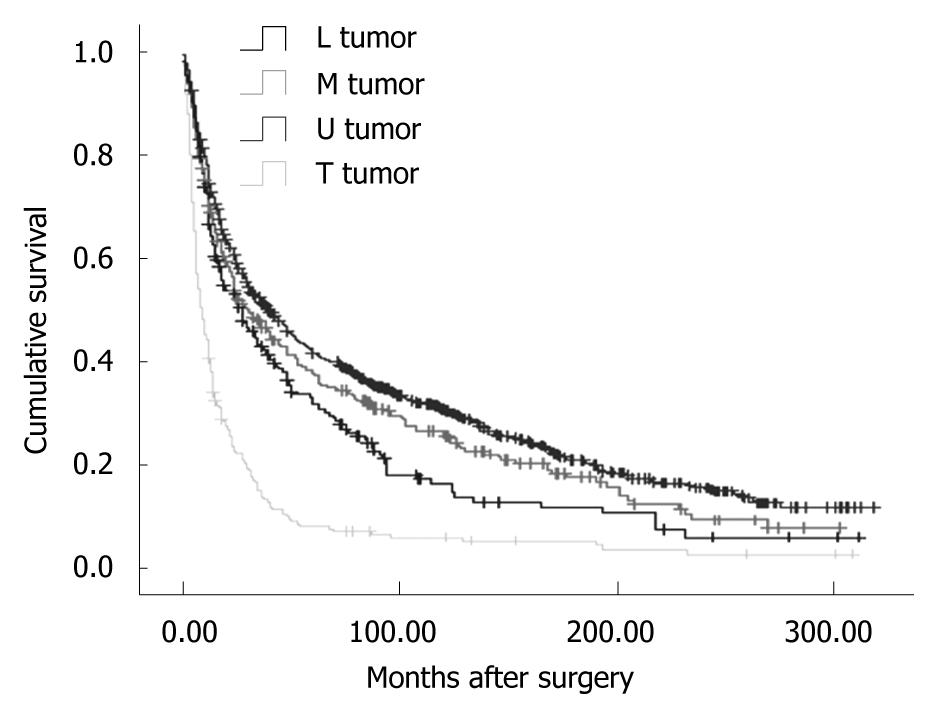

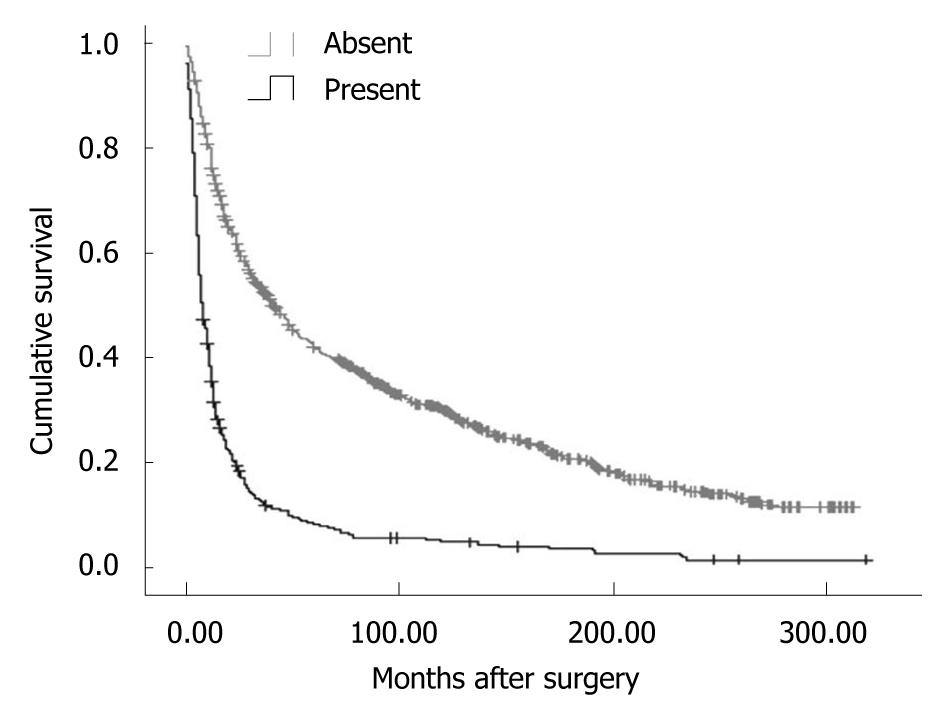

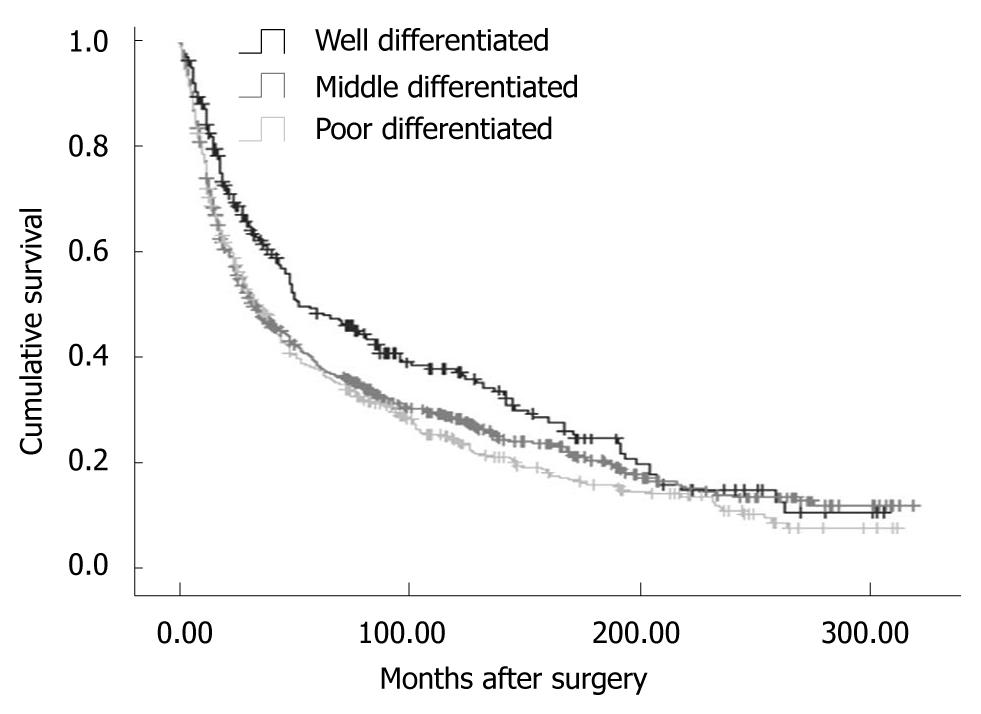

Overall, the 5-year disease-specific survival rate was 29.57%. The survival was observed significantly different in patients with different cancer locations (5-year disease-specific survival rate, L tumor vs M tumor vs U tumor vs T tumor: 33.11% vs 30.46% vs 25.66% vs 7.59%, χ2 = 190.27, P = 0.000) (Figure 1). In addition, the cases with distant metastasis received a poorer prognosis than those without distant metastasis (5-year disease-specific survival rate, 33.50% vs 7.56%, χ2 = 372.21, P = 0.000) (Figure 2). Furthermore, the cases with different histologic types were investigated with a different prognosis (5-year disease-specific survival rate, well differentiated tumors vs middle differentiated tumors vs poor differentiated tumors: 39.27% vs 29.67% vs 25.03%, χ2 = 12.37, P = 0.002) (Figure 3).

There were several studies that have investigated the factors influencing prognosis[13,14]. The conclusions of the reports were controversial, though most of them used the Cox proportional hazard model to find the relation between survival time and patient characteristics, and clinical and pathological factors in patients with gastric cancer.

After evaluating the clinic-pathological factors of 738 patients, Kulig et al[7] reported that patient age, depth of tumor infiltration, tumor location, and metastatic node ratio were identified as independent prognostic factors in a Cox proportional hazards model. In addition, Shiraishi et al[15] reported that independent prognostic factors of gastric cancer were serosal invasion, extragastric lymph node metastasis and liver metastasis, but survival was not significantly associated with any of the patient factors or operation factors, including the extent of lymph node dissection. In our study, age at diagnosis, past history, surgical curative degree, Borrmann type, Lauren’s classification, pT stage, and pN stage were significant prognostic factors in Cox models. There was a small difference between our study and other reports. In the final model of log-normal analysis, we investigated that cancer location, distant metastasis and histologic types were significantly related to the survival. The outcomes were also verified by disease-specific survival analysis. However, the association between above factors and survival were not observed. In log-normal analysis, Pourhoseingholi et al[5] observed that distant metastasis, histology type and pT stage were significant prognostic factors after retrospectively studying 746 Iranian patients. Moreover, distant metastasis was a significant prognostic factor only in log-normal analysis, not in the Cox model.

Compared to the Cox model, the evaluation criteria in our study indicated log-normal regression was more powerful not only in the full model, but also in the final one. In the final model, the selected prognostic factors in the log-normal model were different compared to those in the Cox model. Furthermore, the data strongly supported the log-normal regression in the full and final models, and might lead to more precise results as an alternative for Cox.

In conclusion, according to the results of our study, age at diagnosis, past history, cancer location, distant metastasis status, surgical curative degree, combined other organ resection, histology types, Borrmann type, Lauren’s classification, pT stage, total dissected nodes and pN stage were significant prognostic factors of gastric cancer. It is suggested that log-normal regression model can be a useful statistical model to evaluate prognostic factors instead of the Cox proportional hazard model.

Most of studies used the Cox proportional hazard model to find the relation between survival time and covariates of patients with gastric cancer (GC). On the other hand, some studies reported that log-normal regression could estimate the parameter more efficiently than the Cox model. However, the efficiency of log-normal regression was still controversial.

In this retrospective study, the authors elucidated the factors affecting the survival of patients with GC using log-normal regression, and to compare these results with the Cox model.

It is suggested that log-normal regression model can be a useful statistical model to evaluate prognostic factors instead of the Cox proportional hazard model.

Overall the study was well designed, performed, and analyzed. The very minor, but important parameters should be added in analysis.

| 1. | Yokota T, Ishiyama S, Saito T, Teshima S, Shimotsuma M, Yamauchi H. Treatment strategy of limited surgery in the treatment guidelines for gastric cancer in Japan. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:423-428. |

| 2. | Adachi Y, Shiraishi N, Kitano S. Modern treatment of early gastric cancer: review of the Japanese experience. Dig Surg. 2002;19:333-339. |

| 3. | Ohdaira H, Noro T, Terada H, Kameyama J, Ohara T, Yoshino K, Kitajima M, Suzuki Y. New double-stapling technique for esophagojejunostomy and esophagogastrostomy in gastric cancer surgery, using a peroral intraluminal approach with a digital stapling system. Gastric Cancer. 2009;12:101-105. |

| 4. | Vecchione L, Orditura M, Ciardiello F, De Vita F. Novel investigational drugs for gastric cancer. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;18:945-955. |

| 5. | Pourhoseingholi MA, Moghimi-Dehkordi B, Safaee A, Hajizadeh E, Solhpour A, Zali MR. Prognostic factors in gastric cancer using log-normal censored regression model. Indian J Med Res. 2009;129:262-267. |

| 6. | Moghimi-Dehkordi B, Safaee A, Zali MR. Comparison of colorectal and gastric cancer: survival and prognostic factors. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:18-23. |

| 7. | Kulig J, Sierzega M, Kolodziejczyk P, Popiela T. Ratio of metastatic to resected lymph nodes for prediction of survival in patients with inadequately staged gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2009;96:910-918. |

| 8. | Marrelli D, Pedrazzani C, Corso G, Neri A, Di Martino M, Pinto E, Roviello F. Different pathological features and prognosis in gastric cancer patients coming from high-risk and low-risk areas of Italy. Ann Surg. 2009;250:43-50. |

| 9. | Ichikawa D, Kubota T, Kikuchi S, Fujiwara H, Konishi H, Tsujiura M, Ikoma H, Nakanishi M, Okamoto K, Sakakura C. Prognostic impact of lymphatic invasion in patients with node-negative gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:111-114. |

| 10. | Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma-2nd English Edition. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10-24. |

| 11. | International Union Against Cancer. In: Sobin LH, Wittekind CH, editors. TNM classification of malignant tumors. 5th ed. New York: Wiley 1997; . |

| 12. | Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA. World Health Organization classification of tumors-pathology and genetics of the digestive system. 2000: 38. . |

| 13. | Liu X, Xu Y, Long Z, Zhu H, Wang Y. Prognostic significance of tumor size in T3 gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1875-1882. |

| 14. | Park JC, Lee YC, Kim JH, Kim YJ, Lee SK, Hyung WJ, Noh SH, Kim CB. Clinicopathological aspects and prognostic value with respect to age: an analysis of 3,362 consecutive gastric cancer patients. J Surg Oncol. 2009;99:395-401. |

| 15. | Shiraishi N, Sato K, Yasuda K, Inomata M, Kitano S. Multivariate prognostic study on large gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2007;96:14-18. |

Peer reviewer: Ki-Baik Hahm, MD, PhD, Professor, Gachon Graduate School of Medicine, Department of Gastroenterology, Lee Gil Ya Cancer and Diabetes Institute, Lab of Translational Medicine, 7-45 Songdo-dong, Yeonsu-gu, Incheon, 406-840, Korea

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Rutherford A E- Editor Ma WH