Published online Jun 21, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i23.2838

Revised: November 25, 2010

Accepted: December 2, 2010

Published online: June 21, 2011

AIM: To study, whether the association of Schatzki rings with other esophageal disorders support one of the theories about its etiology.

METHODS: From 1987 until 2007, all patients with newly diagnosed symptomatic Schatzki rings (SRs) were prospectively registered and followed. All of them underwent structured interviews with regards to clinical symptoms, as well as endoscopic and/or radiographic examinations. Endoscopic and radiographic studies determined the presence of an SR and additional morphological abnormalities.

RESULTS: One hundred and sixty-seven patients (125 male, 42 female) with a mean age of 57.1 ± 14.6 years were studied. All patients complained of intermittent dysphagia for solid food and 113 (79.6%) patients had a history of food impaction. Patients experienced symptoms for a mean of 4.7 ± 5.2 years before diagnosis. Only in 23.4% of the 64 patients who had endoscopic and/or radiological examinations before their first presentation to our clinic, was the SR previously diagnosed. At presentation, the mean ring diameter was 13.9 ± 4.97 mm. One hundred and sixty-two (97%) patients showed a sliding hiatal hernia. Erosive reflux esophagitis was found in 47 (28.1%) patients. Twenty-six (15.6%) of 167 patients showed single or multiple esophageal webs; five (3.0%) patients exhibited eosinophilic esophagitis; and four (2.4%) had esophageal diverticula. Four (7%) of 57 patients undergoing esophageal manometry had non-specific esophageal motility disorders.

CONCLUSION: Schatzki rings are frequently associated with additional esophageal disorders, which support the assumption of a multifactorial etiology. Despite typical symptoms, SRs might be overlooked.

- Citation: Müller M, Gockel I, Hedwig P, Eckardt AJ, Kuhr K, König J, Eckardt VF. Is the schatzki ring a unique esophageal entity? World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(23): 2838-2843

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i23/2838.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i23.2838

Lower esophageal (Schatzki) rings are found in 6%-14% of routine barium radiographs[1-4]. Even though most Schatzki rings (SRs) are asymptomatic, they are considered to be the most common cause of episodic dysphagia for solids and food impaction in adults[5,6]. Since their first description in 1944[7], the etiology and pathogenesis of the SRs has remained obscure and little is known about their association with other structural and functional abnormalities of the esophagus. Theories about their origin include congenital, anatomical, and inflammatory factors as the most likely events that lead to a circular constriction of the esophagogastric junction[8-12].

Therefore, the aims of this study were: (1) to investigate whether the lower esophageal (Schatzki) ring is associated with other esophageal disorders; (2) to determine whether dysphagia is due to the presence of SRs or additional esophageal disorders; and (3) to determine whether one of the pathogenic theories could be supported.

From 1987 until 2007, all patients with newly diagnosed symptomatic SRs were prospectively registered and followed. The diagnosis of SRs was based on the results of radiographic and/or endoscopic studies. In 119 patients, radiographic and endoscopic studies showed an SR. Fourteen patients had only radiographic and 34 only endoscopic studies. All patients underwent structured interviews to assess clinical symptoms.

At the initial investigation and at each follow-up visit, structured interviews were performed. Questions concentrated on clinical symptoms such as the occurrence of food impaction, and frequency of dysphagia, heartburn and regurgitation (less than once a week, weekly, daily, or several times a day).

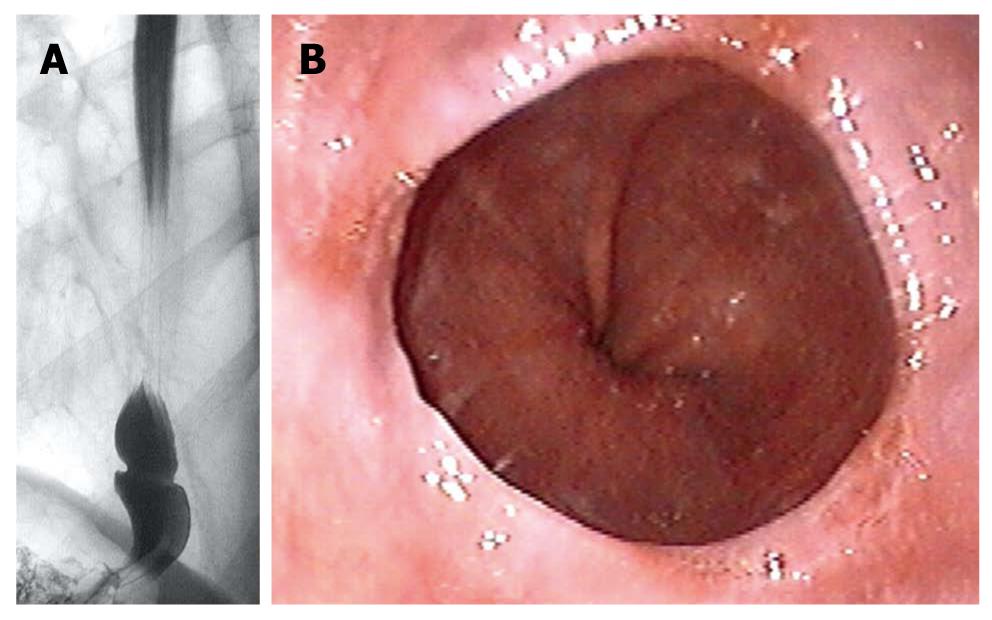

Radiographic studies (n = 133) were performed by senior staff radiologists using the prone-oblique, full-column technique. To distend the lower esophagus maximally, patients were asked to take a deep breath and to perform a Valsalva maneuver during the course of swallowing. Diagnosis of SR (Figure 1A) was based on the presence of a fixed, symmetric, thin (< 4 mm) structure, which intersected the esophagus perpendicular to its long axis, at the squamocolumnar junction[6,13]. The diameter of the lower esophageal ring was measured directly from the radiographic picture in the area of the narrowing. An esophageal web is defined as a thin (< 2 mm) eccentric membrane that can occur anywhere in the esophagus[14]. A sliding hiatal hernia was diagnosed when a pouch was visible between the tubular esophagus and the diaphragmatic narrowing (length of the pouch ≤ 3 cm = small hernia, > 3 cm = large hernia)[15]. Diagnosis of diverticulum was based on the presence of a pouch in the esophagus (Zenker’s diverticulum: pouch in the pharyngoesophageal area; midesophageal diverticulum: pouch in the mid esophagus; epiphrenic diverticulum: pouch just proximal to diaphragm)[14].

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (n = 153) was performed by senior staff gastroenterologists using a variety of upper gastrointestinal endoscopes (Olympus, Hamburg, Germany), which varied in caliber from 8.5 to 9.5 mm. The endoscopic mucosal appearance determined the presence or absence of esophagitis as well as further morphological abnormalities of the upper gastrointestinal tract. SR (Figure 1B) was defined as a thin, symmetric, mucosal structure located at the esophagogastric junction[3]. A sliding hiatal hernia was diagnosed when gastric mucosa extended for > 1.5 cm above the diaphragm[16]. An esophageal web was defined as a thin (no more than 1.5 mm), eccentric membrane, located above the esophagogastric junction[14]. The degree of esophagitis was classified into four stages according to Savary and Miller[17]. If there were mucosal alterations in addition to reflux esophagitis, biopsies were taken from the esophagus. The presence of ≥ 20 eosinophils per high-power field in the histopathological examination was used as the criterion to diagnose eosinophilic esophagitis[18].

To exclude an esophageal motility disorder, 57 patients underwent esophageal manometry. Stationary esophageal manometry was performed with the use of a low-compliance capillary perfusion system (Mui Scientific, Mississauga, ON, Canada), using an eight-channel multi-lumen catheter with a 4.5-mm diameter. The four distal openings were 1 cm apart and the four proximal openings were 5 cm apart. Both sets were radially oriented. The manometric tracings were recorded by a computer polygraph system (Standard Instruments, Karlsruhe, Germany). Manometry was performed using a stationary pull-through method with the catheter introduced transnasally into the stomach. Manometry was carried out and interpreted according to the recommendations of the American Society of Gastroenterology[19]. Non-specific motor disturbance was defined as contractile abnormalities that are insufficient to establish a diagnosis of achalasia, diffuse esophageal spasm or typical scleroderma-like esophageal dysfunction[19,20].

Numerical variables are expressed as mean ± SD, counts and ranges. Categorical variables are described using frequencies and percentages. Statistical significance of the differences between groups was assessed by Mann-Whitney U test for metric variables, by the Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test for trends for ordered categorical variables and by Pearson χ2 test for binary variables. A two-tailed P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows version 15.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

One hundred and sixty-seven patients (124 male, 43 female) with a mean age of 57.1 ± 14.6 years were studied. Patients experienced symptoms for a mean of 4.7± 5.2 years before diagnosis. Sixty-four (38.3%) of the 167 patients had endoscopic and/or radiological examinations before their first presentation to our clinic, but only in 15 (23.4%) of these patients was SR was previously diagnosed. In 35 (87.5%) of the 40 patients who received an endoscopic examination, the SR had not been diagnosed, and in 14 (70%) of the 20 patients who underwent radiological examinations, the diagnosis could not be determined.

One hundred and twelve patients received radiological and endoscopic examinations at their initial presentation to our hospital. Endoscopy or a barium swallow accurately diagnosed the SR in all 112 patients in whom both methods were used. In the 34 patients who were only examined by endoscopy, the correct diagnosis was made in all cases, whereas the diagnosis was only made in 14 (66.7%) of the 21 patients who underwent radiological examinations first. In the seven patients without an initial radiological diagnosis, the SR was identified on subsequent endoscopy.

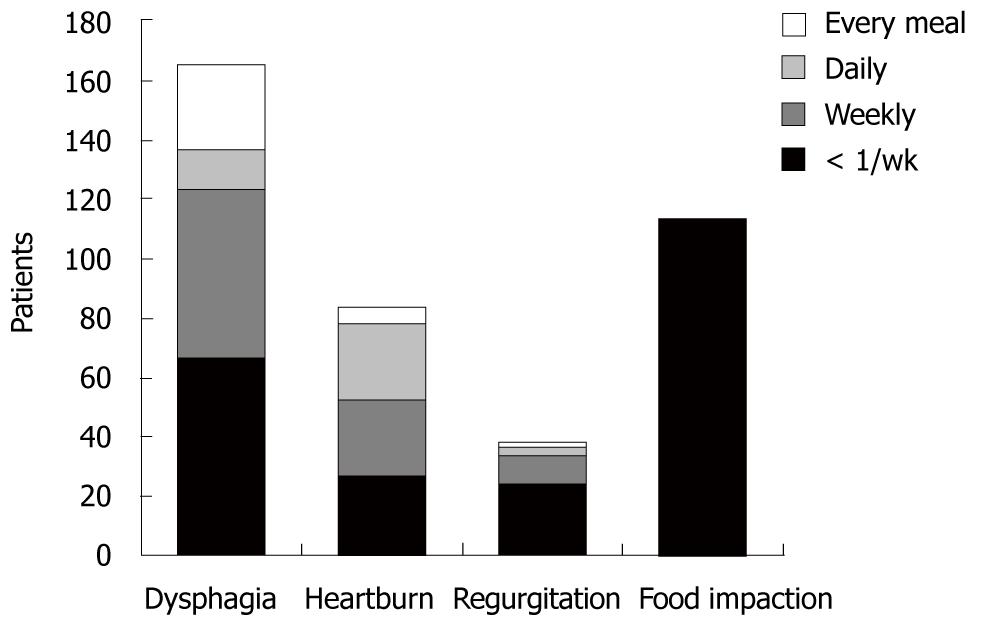

Clinical symptoms at initial presentation are shown in Figure 2. All patients complained of intermittent dysphagia for solid food: 66 patients (39.5%) less than once per week, 58 (34.7%) weekly, 14 (8.4%) daily, and 29 (16.4%) with every meal. One hundred and thirteen (79.6%) of the 167 patients had a history of food impaction. Forty (23.9%) patients described regurgitation and 87 (52.1%) complained of occasional heartburn.

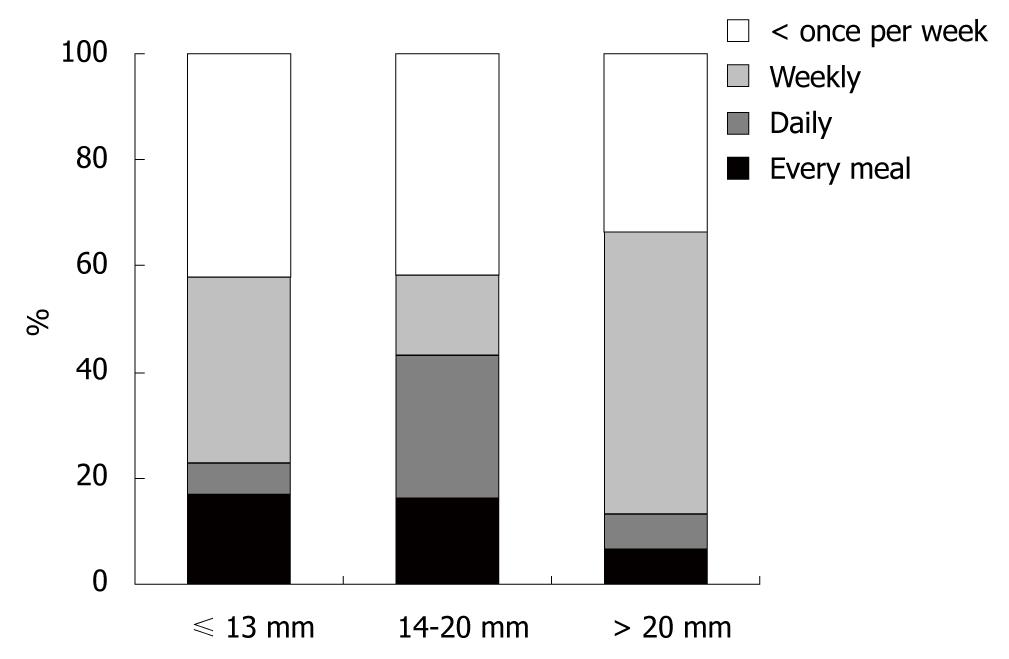

The diameter of the lower esophageal ring was evaluated in 126 patients undergoing radiographic studies, and in 27 patients, endoscopic estimation was used with open biopsy forceps (7 mm) being the reference standard. In 14 patients, no measurement was performed. At initial presentation, the mean ring diameter was 13.9 ± 4.97 mm (range: 5-25 mm). Eighty-three (54.2%) of 153 patients had a ring size ≤ 13 mm, and 15 (9.8%) had a ring size > 20 mm. There was no correlation between ring size and frequency of dysphagia (P = 0.29, Figure 3). Also, sex (P = 1.0) and age ≤ 40 or > 40 years (P = 0.93) had no influence on the frequency of dysphagia. Demographic data, ring size and clinical findings of all patients with Schatzki rings are shown in Table 1.

| Variables | SR (n = 167) | SR with erosive esophagitis(n = 471) | SR with esophageal webs(n = 261) |

| Age (yr) | 57.1 ± 14.6 | 58.4 ± 13.7 | 54.4 ± 18.9 |

| Sex (n) | |||

| Male | 124 | 33 | 18 |

| Female | 43 | 14 | 8 |

| Ring size (mm) | 13.9 ± 4.97 | 14.1 ± 5.3 | 12.2 ± 3.8 |

| Dysphagia, n (%) | |||

| Every meal | 29 (17.4) | 7 (14.9) | 8 (30.8) |

| Daily | 14 (8.4) | 3 (6.4) | 3 (11.5) |

| Weekly | 58 (34.7) | 17 (36.2) | 6 (23.1 ) |

| < 1 x/wk | 66 (39.5) | 20 (42.6) | 9 (34.6) |

| Food impaction, n (%) | 113 (79.6) | 34 (72.3) | 18 (69.2) |

| Heartburn, n (%) | 86 (57.1) | 29 (61.7) | 12 (46.1) |

| Regurgitation, n (%) | 40 (23.9) | 11 (23.4) | 6 (23.1) |

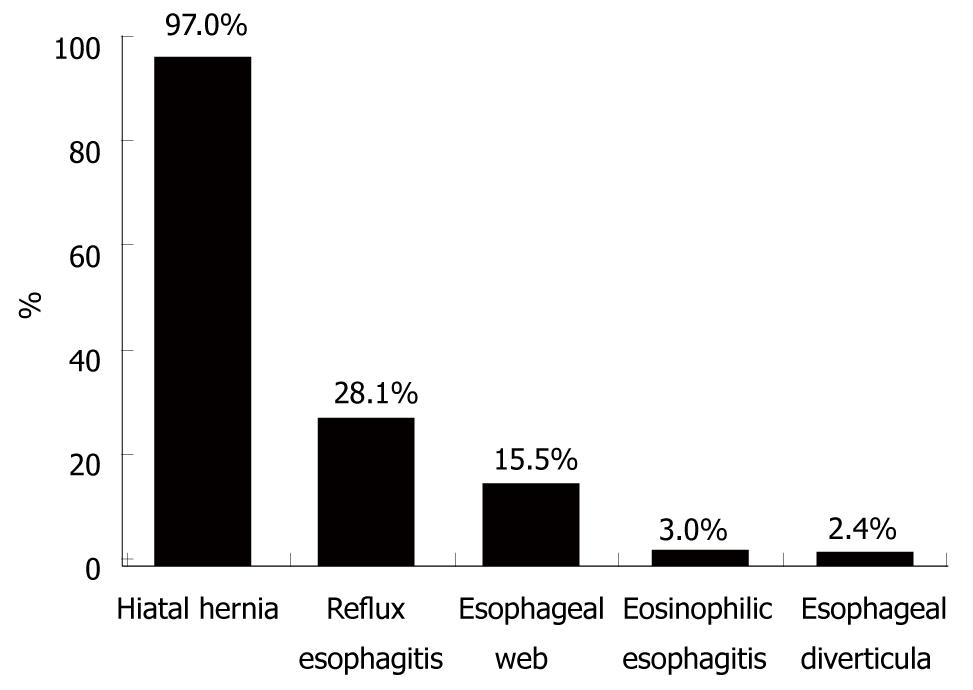

A sliding hiatal hernia was found in 162 (97%) of 167 patients (n = 28 radiographic examinations, n = 29 endoscopic examinations, n = 105 radiographic and endoscopic examinations). One hundred and nineteen patients exhibited a small hernia and 43 had a large one. data, ring size and clinical findings of patients with Schatzki rings and additional erosive esophagitis, and /or esophageal webs are demonstrated in Table 1.

Further structural and functional abnormalities of the esophagus were diagnosed in 87 (52%) of 167 patients (Figure 4). The most frequent additional endoscopic finding was erosive reflux esophagitis, which was found in 47 (28.1%) patients; 40 (85.1%) of whom had stage I esophagitis, whereas seven (14.9%) presented with stage II and III, and none with stage IV. All but one patient with reflux esophagitis showed a hiatal hernia. Twenty-six (15.6%) of 167 patients showed single (n = 15) or multiple ≥ 2 (n = 11) esophageal webs, and four (2.4%) patients had esophageal diverticula. Two of the four patients with esophageal diverticula showed a Zenker’s diverticulum, and in two patients, midesophageal diverticula were diagnosed. Four patients exhibited erosive reflux esophagitis in addition to esophageal webs. Five (16.6%) of the 30 patients in whom biopsies of the esophagus were taken exhibited histopathological signs of eosinophilic esophagitis. All but one patient complained of food impaction, whereas the frequency of dysphagia varied in this subgroup of patients (two patients, every meal; one patient, daily; and two patients, less than once per week).

Four (7%) of 57 patients undergoing esophageal manometry showed pathological results (two with non-specific motor disturbance, one with low contraction amplitudes, and one with diffuse esophageal spasm). Patients with an additional motility disorder of the esophagus showed a higher frequency of dysphagia than patients without (P = 0.03), although there was no difference in ring diameter (patients with motility disorders, 13.53 ± 3.6 mm; patients without, 13.7 ± 4.1 mm; P = 0.92).

The mean ring diameter in patients with additional esophageal webs (12.3 ± 3.8 mm) was smaller than in patients without webs (14.2 ± 5.1 mm) (P = 0.057). However, there were no differences in the frequency of dysphagia in patients with further structural abnormalities of the esophagus (sliding hernia, P = 0.1; erosive esophagitis, P = 0.48; and esophageal webs, P = 0.15) in comparison to the patients with an SR alone.

The lower esophageal SR is a common clinical finding and the most common cause of intermittent dysphagia, especially after consumption of solid food[6,21]. However, little is known about its etiology, its pathogenesis, or its association with other esophageal disorders. In addition, the clinical importance of associated disorders has not been described.

In our study, we were able to show that symptomatic SRs cannot always be diagnosed with a single imaging technique, and that the SR is not a unique entity. It is frequently associated with other esophageal disorders, such as hiatal hernias, reflux esophagitis and esophageal webs. In addition, ring size and most other structural abnormalities do not predict symptoms. In contrast, dysphagia was more common in patients with an additional motility disorder, and food impaction was the most common presentation in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Whether the frequent association with hiatal hernias and inflammatory esophagitis plays a pathogenic role remains unclear, but a multifactorial etiology is suspected.

In the present study, we confirmed previous observations that patients with symptomatic SRs complain about episodic dysphagia for solid food (mean duration 4.7 years prior to diagnosis), and more than two-thirds develop food impaction. Despite the typical clinical presentation, there was a significant diagnostic delay. Prior to presentation to our hospital, diagnosis of an SR was made in less than half of symptomatic patients; a surprisingly low number of patients. One of the difficulties in detecting lower esophageal rings might be related to the fact that the radiographic and endoscopic visualization depends on proper distension of the esophagogastric region beyond the caliber of the ring, which is often not accomplished[22]. This is especially true for wider rings with a luminal diameter > 13 mm[23]. In such instances, the radiographic examination has been shown to be superior to endoscopy in detecting lower esophageal rings[24]. In contrast, the present study could show a better diagnostic yield of endoscopy as compared with a barium swallow. This is most likely related to our special attention to membranous structures. Our findings suggest that a second imaging study should be performed in patients with typical clinical presentation if the first study fails to make the diagnosis of SR.

The current investigation showed that SRs are not a unique entity, but associated with additional esophageal disorders in 57% of symptomatic patients. Besides the nearly unanimous association with a hiatal hernia[2,24], we found a common association with reflux esophagitis and esophageal webs. In addition, esophageal diverticula were occasionally diagnosed. However the presence of additional structural abnormalities of the esophagus did not change the clinical presentation. Dysphagia was not more common in these patients. Even in patients with additional esophageal webs, whose ring diameters were generally smaller, dysphagia was not more common. These findings suggest that the ring diameter alone may not be responsible for the observed symptoms.

In contrast, dysphagia was more frequently observed in patients with non-specific motility disorders, regardless of ring size, which suggests that the motility disorder may be responsible for the symptoms. Therefore, manometry should be considered in patients with wide ring diameters and symptoms of dysphagia. In addition, we found that intermittent bolus obstructions were a very frequent finding in those patients with an additional diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis, and clinicians should keep this clinical entity in mind. Therefore, the presence of an SR should not deter the endoscopist from taking esophageal biopsies in a patient in whom eosinophilic esophagitis remains a possibility. In fact, ring-like structures are common in eosinophilic esophagitis, and we became aware of this entity only a decade ago. Although an association of eosinophilic esophagitis and SRs has been previously suggested, it is not known if this is caused by shared clinical and endoscopic findings, or rather a shared pathogenesis[25,26]. Common clinical features might also explain the frequent coexistence of esophageal webs and eosinophilic esophagitis in our study. However, it is not clear if the additional esophageal disorders occur by chance, or if there is a common pathogenesis. The etiology of SRs remains obscure, and several theories about their etiology and pathogenesis exist. One of these is the developmental theory that holds that the presence of a congenital mucosal ridge at the esophagogastric junction is a rather frequent anatomical phenomenon that could fold in a valve-like fashion to create the ring[3,8]. Arguing against this, is the fact that the majority of symptomatic individuals were over the age of 40 years in the present and previous studies[27]. In the so called plication theory, Stiennon has postulated that longitudinal shortening in the presence of a hiatal hernia may lead to folding of redundant esophageal mucosa[11]. Consistent with this theory is the fact that most of the patients in the present study had a sliding hiatal hernia. However, it still remains unclear why some patients with a hernia develop an SR and others do not. Therefore, the plication theory is unlikely to be the only cause for the development of SRs. Currently, the inflammation theory with gastroesophageal reflux as the main cause of inflammation, is the most popular theory[28], and consequently, some authors have recommended an antireflux regimen to prevent symptomatic recurrence[29,30]. Others have pointed out that, if less than two-thirds of patients are found to have pathological gastroesophageal reflux[31,32], it might not be the main pathogenic factor. Similar to the latter findings, even if reflux esophagitis were one of the most frequent associated esophageal disorders in the present study, less than one-third of all investigated patients showed endoscopic signs of erosive esophagitis, and only half complained of occasional heartburn, which suggests that gastroesophageal reflux is not the only cause for the development and narrowing of the SR. Therefore, we assume that the etiology of SR is multifactorial.

In conclusion, SRs might be overlooked in endoscopic and/or radiological examinations. Therefore, in patients with a typical clinical presentation, a second diagnostic imaging should be considered. Other esophageal disorders are frequently observed and should be kept in mind; most of which do not alter clinical presentation. Non-specific motility disorders and eosinophilic esophagitis should be considered, especially when frequent dysphagia or food impaction is present. With regard to the etiology of SRs, the present findings suggest a multifactorial genesis, which supports the inflammation theory as well as the plication theory.

The Schatzki ring (SR) is the most common cause of episodic dysphagia to solid food. Nevertheless its etiology and pathogenesis remains unknown and little is known about its association with other structural and functional abnormalities of the esophagus. Theories regarding its origin include inflammatory, developmental, and congenital factors as the most likely events leading to a circular constriction of the esophagogastric junction. In addition, the clinical importance of associated disorders has not been described.

Currently, the ‘inflammation theory’ with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) as the main cause of inflammation, is the most popular theory. However, prospective studies have documented an association with GERD in less than two thirds of patients, suggesting that additional pathogenic factors might be responsible for the development of the SR.

It is known that SRs are associated with hiatal hernias and reflux esophagitis, whereas this is the first study that could show the frequent association of SRs with additional esophageal disorders, most of which do not alter clinical presentation. Nonspecific motility disorders and eosinophilic esophagitis should be considered, especially when frequent dysphagia or food impactions are present, respectively. In regards to the etiology of SRs the present findings suggest a multifactorial pathogenesis. Furthermore, despite the typical clinical presentation SRs might be overlooked in endoscopic and /or radiological examinations.

SRs are frequently associated with other esophageal disorders. These should be sought, especially when frequent dysphagia or food impaction is the presenting symptom. SRs might be overlooked on radiographic or endoscopic examinations, therefore, a second diagnostic modality should be used when suspicion remains high.

“Stiennon’s plication theory”, postulated that longitudinal shortening in the presence of an hiatal hernia may lead to folding of a redundant esophageal mucosa, creating the SR.

The manuscript reads very well and flows nicely. The conclusions are supported by the data and the limitations are well addressed. In addition, the study is novel and the topic chosen is original.

| 1. | Kramer P. Frequency of the asymptomatic lower esophageal contractile ring. N Engl J Med. 1956;254:692-694. |

| 2. | Keyting WS, Baker GM, Mccarver RR, Daywitt AL. The lower esophagus. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1960;84:1070-1075. |

| 3. | Goyal RK, Glancy JJ, Spiro HM. Lower esophageal ring. 1. N Engl J Med. 1970;282:1298-1305. |

| 4. | Schatzki R, GARY JE. The lower esophageal ring. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1956;75:246-261. |

| 5. | Schatzki R. The lower esophageal ring. long term follow-up of symptomatic and asymptomatic rings. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1963;90:805-810. |

| 6. | Schatzki R, Gary JE. Dysphagia due to a diaphragm-like localized narrowing in the lower esophagus (lower esophageal ring). Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1953;70:911-922. |

| 7. | Templeton FE. X-ray examination of the stomach: a description of the roentgenologic anatomy, physiology and pathology of the esophagus, stomach and duodenum. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1944; . |

| 8. | Longstreth GF. Familial lower esophageal rings. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:443. |

| 9. | Goyal RK, Bauer JL, Spiro HM. The nature and location of lower esophageal ring. N Engl J Med. 1971;284:1175-1180. |

| 10. | Edelson ZC, Rosenblatt MS. Hiatal hernia and lower esophageal ring. Am J Surg. 1962;104:879-882. |

| 11. | Stiennon OA. The anatomic basis for the lower esophageal contraction ring. plication theory and its applications. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1963;90:811-822. |

| 12. | Rinaldo JA, Gahagan T. The narrow lower esophageal ring: pathogenesis and physiology. Am J Dig Dis. 1966;11:257-265. |

| 13. | Ott DJ, Gelfand DW, Wu WC, Castell DO. Esophagogastric region and its rings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;142:281-287. |

| 14. | Tobin RW. Esophageal rings, webs, and diverticula. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;27:285-295. |

| 15. | Heitmann P, Wolf BS, Sokol EM, Cohen BR. Simultaneous cineradiographic-manometric study of the distal esophagus: small hiatal hernias and rings. Gastroenterology. 1966;50:737-753. |

| 16. | Wright RA, Hurwitz AL. Relationship of hiatal hernia to endoscopically proved reflux esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1979;24:311-313. |

| 17. | Savary M, Miller G. The esophagus: Handbook and atlas of endoscopy. Solothurn, Switzerland: Verlag Gassmann AG 1978; 135-139. |

| 18. | Khan S, Orenstein SR, Di Lorenzo C, Kocoshis SA, Putnam PE, Sigurdsson L, Shalaby TM. Eosinophilic esophagitis: strictures, impactions, dysphagia. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:22-29. |

| 19. | Kahrilas PJ, Clouse RE, Hogan WJ. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on the clinical use of esophageal manometry. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1865-1884. |

| 20. | Clouse RE, Staiano A. Manometric patterns using esophageal body and lower sphincter characteristics. Findings in 1013 patients. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:289-296. |

| 21. | Mitre MC, Katzka DA, Brensinger CM, Lewis JD, Mitre RJ, Ginsberg GG. Schatzki ring and Barrett’s esophagus: do they occur together? Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:770-773. |

| 22. | Frileux C, Gillot C, Choquart P. [Ischemia or acute vascular stasis of a limb related to psychopathological behavior. Pathominia]. J Chir (Paris). 1976;111:163-166. |

| 23. | Ott DJ, Chen YM, Wu WC, Gelfand DW, Munitz HA. Radiographic and endoscopic sensitivity in detecting lower esophageal mucosal ring. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;147:261-265. |

| 24. | Castell DO, Richter JE. The esophagus. Philadelphia: Lipinoctt Williams & Wilkins 1999; . |

| 25. | Nurko S, Teitelbaum JE, Husain K, Buonomo C, Fox VL, Antonioli D, Fortunato C, Badizadegan K, Furuta GT. Association of Schatzki ring with eosinophilic esophagitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;38:436-441. |

| 26. | Desai TK, Stecevic V, Chang CH, Goldstein NS, Badizadegan K, Furuta GT. Association of eosinophilic inflammation with esophageal food impaction in adults. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:795-801. |

| 27. | Marshall JB, Kretschmar JM, Diaz-Arias AA. Gastroesophageal reflux as a pathogenic factor in the development of symptomatic lower esophageal rings. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1669-1672. |

| 28. | Ott DJ, Ledbetter MS, Chen MY, Koufman JA, Gelfand DW. Correlation of lower esophageal mucosal ring and 24-h pH monitoring of the esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:61-64. |

| 29. | Wills JC, Hilden K, Disario JA, Fang JC. A randomized, prospective trial of electrosurgical incision followed by rabeprazole versus bougie dilation followed by rabeprazole of symptomatic esophageal (Schatzki’s) rings. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:808-813. |

| 30. | Sgouros SN, Vlachogiannakos J, Karamanolis G, Vassiliadis K, Stefanidis G, Bergele C, Papadopoulou E, Avgerinos A, Mantides A. Long-term acid suppressive therapy may prevent the relapse of lower esophageal (Schatzki’s) rings: a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1929-1934. |

| 31. | Eckardt V, Dagradi AE, Stempien SJ. The esophagogastric (Schatzki) ring and reflux esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1972;58:525-530. |

Peer reviewer: Piero Marco Fisichella, MD, Assistant Professor of Surgery, Medical Director, Swallowing Center, Loyola University Medical Center, Department of Surgery, Stritch School of Medicine, 2160 South First Avenue, Room 3226, Maywood, IL 60153, United States

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Ma WH