ABSOLUTE AND EXPANDED INDICATIONS OF ESD FOR EGC

The curability of EGC depends on the complete removal of the cancerous lesion and its metastatic lymph nodes. Fortunately, because a significant proportion of EGC has no lymph node metastasis, limited surgery, such as ESD, can be legitimately performed in many countries.

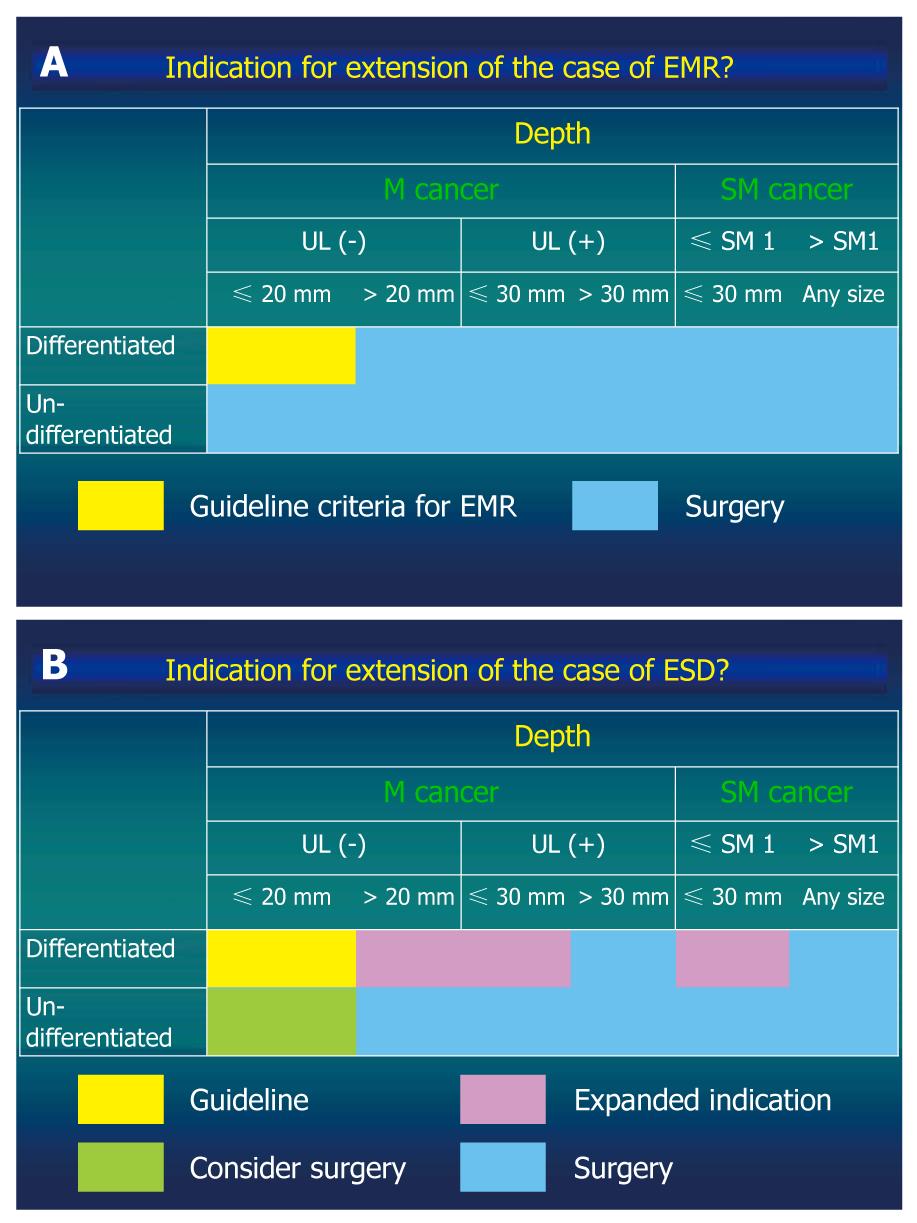

Traditionally accepted indications for endoscopic resection of EGC are small intramucosal EGCs of intestinal histology type. The rationale for this recommendation is based on the knowledge that larger lesions or diffuse histology lesions are more likely to extend into the submucosal layer and thus have a higher risk of lymph node metastasis. In addition, resection of a large lesion was not technically feasible until the ESD procedure was developed. Therefore, at present, the accepted indications for endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) according to the gastric cancer treatment guidelines published in 2001 by the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association are: (1) well-differentiated elevated cancers less than 2 cm in diameter; and (2) small (< 1 cm) depressed lesions without ulceration. These lesions must also be moderately or well-differentiated cancers confined to the mucosa, and have no lymphatic or vascular involvement[5,6]. However, it has been clinically observed that currently accepted indications for EMR may be too strict, leading to unnecessary surgery[7].

Further studies by Gotoda et al[8] have defined new criteria to expand the indications for endoscopic treatment of gastric cancer. The ESD method has been developed to dissect directly along the submucosal layer using specialized devices. Preliminary studies have been published on the advantage of ESD over conventional EMR for the removal of larger or ulcerated EGC lesions en bloc. Thus, ESD allows the precise histological assessment of the resected specimen and may prevent residual disease and local recurrence. Gotoda et al[8] analyzed 5265 EGC patients who underwent gastrectomy with lymph node dissection. They provided important information on the risks of lymph node metastasis, wherein the differentiated gastric cancer with a nominal risk of lymph node metastasis was defined. They proposed expanded criteria for endoscopic resection: (1) mucosal cancer without ulcer findings, irrespective of tumor size; (2) mucosal cancer with an ulcer ≤ 3 cm in diameter; and (3) minimal (≤ 500 μm from the muscularis mucosa) submucosal invasive cancer ≤ 3 cm in size (Figure 1)[8,9]. However, extending the indications for ESD remains controversial because the long-term outcomes of these procedures have not been fully documented.

Figure 1 Guideline criteria for endoscopic mucosal resection (A) and expanded criteria for endoscopic submucosal dissection proposed by Gotoda et al[8] and Soetikno et al[9] (B).

EMR: Endoscopic mucosal resection; ESD: Endoscopic submucosal dissection.

RECENT EVIDENCE FOR EXPANDED INDICATIONS OF ESD FOR EGC

Over the past 20 years, intraluminal endoscopic surgery, referred to as EMR, has been advanced in Japan and Korea. Recently, EMR and ESD have been widely used to treat EGC without lymph node metastasis. EMR is indicated when the risk of lymph node metastasis is minimal and when the tumor can be removed en bloc with a loop snare. Therefore, in the guidelines issued by the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association (JGCA), differentiated mucosal cancers measuring less than 2 cm in diameter best fit the above criteria. However, endoscopic resection has also been used for larger lesions without lymph node metastasis. In addition, improved techniques featuring ESD, which involve incision of the mucosa around the lesion followed by direct dissection of the submucosal layer, can provide en bloc resection, regardless of the tumor size. Therefore, provided that there is no metastatic lymph node, and the cancer is confined to mucosa and upper submucosal layer, endoscopic resection featuring ESD can be advocated as a proper management strategy for EGC.

To establish a safe and confident criteria and indication for ESD, we have to classify EGC with and without metastatic lymph nodes and to analyze long-term follow-up data after EMR and ESD. In a recent study of patients who had undergone radical gastrectomy for EGC, none of the 1230 well differentiated mucosa-confined cancers smaller than 3 cm in diameter had associated lymph node metastasis, regardless of the presence of ulceration[8]. Regarding the presence of ulceration in all EGC patients, the probability of lymph node involvement significantly increases in EGC containing an ulcer (3.4%) compared to EGC without an ulcer (0.5%)[8]. In subgroup analysis, cancer that is confined to the mucosa without an ulcer has no lymph node involvement, regardless of size (95% CI, 0%-0.4%). Mucosal cancer with an ulcer showed a size limitation up to 30 mm to be free of lymph node involvement (95% CI, 0%-0.3%). Thus we can conclude that presence of an ulcer and size are factors for indication of ESD for EGC. However, such characterization of EGC based on morphological feature poses certain problems. First, we should consider the life cycle of a malignant ulcer[10]. About one-third of EGCs with depressed morphology can change over time[11]. An EGC with ulceration on initial EGD can change into non-ulcerative EGC with an antisecretory agent. In addition, EGCs with ulceration, which had not appeared ulcerous on previous examination, are sometimes encountered. Nevertheless, there is no evidence in the literature regarding the outcome of ESD for EGC with healing ulcers and fibrotic scarring. In practice, the decision of ESD for EGC with a shallow ulcer often depends on the timing of the diagnosis and on the willingness of the operator. Regarding the division of ulcerative and non-ulcerative as a criterion for ESD[8], there has not been sufficient research to allow a definite decision. Second, there can be inter-observer variation in defining an ulcer in EGC. By definition, ulcers measure 5 mm or larger in diameter and are on exposed submucosa. However, in real endoscopic examination, the differentiation between ulcer and erosion is not always clear. Third, the size of a lesion can be different according to the method of measurement. An endoscopic ruler or a standard size disc patch can be applicable but, in most cases, a lesion is measured by eye in comparing to opened grasp of forceps. Thus, a standard reliable measurement method is required.

Another factor for expanded indication of ESD concerns the invasion depth of EGC. Although the absolute indication for EMR is applicable to only mucosal cancer, there have been some studies of ESD in submucosal cancer. Of the 145 well-differentiated tumors that had invaded less than 500 μm into the submucosa, and were smaller than 30 mm in diameter, none showed evidence of lymph node metastasis, provided that there was no lymphatic or venous invasion. Based on these findings, it was suggested that the criteria for ESD for EGC could be expanded[12-16].

From the surgical literature, the risk of lymph node metastasis appears to depend on the presence of ulcer rather than on the depth of invasion of EGC. A retrospective analysis of patients who underwent surgery for EGC in Korea reported that, among 129 cases of mucosal cancer compatible with expanded indications for EMR or ESD, three patients (2.3%) had lymph node metastasis and, among 52 submucosal cancer cases that met the expanded indications for EMR or ESD, two patients (4%) had lymph node metastasis[17]. The authors suggest that if EMR or ESD had been performed in these patients, it would not have been curative. However, even in this report, differentiated mucosal cancers without ulcers did not have lymph node metastasis, irrespective of size. Thus, these data suggest that a well-differentiated mucosal cancer of any size without ulcer may be considered as an expanded indication for ESD.

Even in the expanded criteria, undifferentiated cancer an indication for surgery. However, studies on feasibility of ESD on undifferentiated EGC have been continuously performed and reported. Ye et al[18] reported that EGC with undifferentiated histology has no lymph node involvement, provided that the cancer is smaller than 25 mm, is confined to the mucosa or upper third of the submucosa, and has no lymphatic involvement. A similar study for signet ring cell carcinoma was reported by Park et al[19]. EGC with signet ring cell histology is a high risk for nodal and organ metastases, while smaller cancers of less than 25 mm that are confined to the SM2 layer and have no lymphatic-vascular involvement have no lymph node involvement. With regard to poorly differentiated EGC, a Korean study reported a somewhat lower risk of lymph node metastasis than expected[20]. On this retrospective analysis of 234 patients with poorly differentiated EGC who underwent radical gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection, half of the cases (n = 116) showed submucosal invasion in the resection specimen and 25.9% (30/116) of those were limited to the upper third (SM1). Lymph node metastasis was found in 3.4% (4/118) of mucosa-confined cancer. For patients with minor submucosal infiltration (SM1), the lymph node metastasis rate was non-existent (0/30). However, with SM2/3 invasion, the lymph node metastasis rate increased sharply to around 30%. Another Korean study[21] focusing on endoscopic resection for undifferentiated-type cancer, such as poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma and signet ring cell carcinoma, showed interesting results. In this study, 58 lesions with undifferentiated EGC (17 poorly differentiated; 41 signet-ring cell) were treated by endoscopic resection. The en bloc and complete resection rates in poorly differentiated cases were 82.4% and 58.8%, respectively, whereas those in signet ring cell were 85.4% and 70.7%. The recurrence rate was 5.1% in complete resection during the follow-up period. Therefore, the authors suggested that endoscopic resection might be a feasible local treatment for undifferentiated EGC if complete resection can be achieved. Although the studies so far are still insufficient to form a conclusion, we could take poorly differentiated cancer with mucosa or minimal submucosal invasion into consideration as a possible candidate for ESD in high-risk surgical patients.

A prospective comparative study was reported in Japan[6] concerning the clinical outcomes of absolute and expanded indication of EMR and ESD. A total of 589 EGC lesions were divided into the guideline group and the expanded group. En bloc, complete, and curative resections were achieved in 98.6 and 93.0, 95.1 and 88.5, and 97.1 and 91.1% of the guideline and expanded criteria lesions, respectively, and the differences between the two groups were significant. The complication risks, such as procedure associated perforation and bleeding, were significantly higher and the completeness of resection was statistically superior in the expanded indication group. However, the overall survival was equally adequate in both groups, and the disease-specific survival rates were 100% in both groups.

LIMITATIONS OF ESD

Lymph node micrometastasis and delayed cancer dissemination after ESD is one of the concerns about endoscopic resection including ESD. Walter et al[22] reported a fulminant case in a 67-year-old male patient with EGC of 12 mm and moderate differentiation. The depth of submucosal invasion was 2.3 mm and the cancer free margin could not be established. The patient underwent gastrectomy and the postoperative stage was pT1 (sm3), pNO (0/58), cM0, L0, V0, G2 (UICC stage Ia). Three months later, an ultrasound revealed a new mass in the liver, and biopsy showed a rapidly growing metastasis of the gastric adenocarcinoma. This case highlights the risk of affected lymph nodes in early gastric cancer and the consequent risk of metastasis, which increases with greater depth of infiltration into the submucosa. Micrometastasis can be a reason for cancer recurrence even after curative surgery[23-27]. According to Cai et al[25], tumor size, macroscopic type, accompanying ulcers, and depth of invasion are strongly associated with micrometastasis in lymph nodes. Therefore, tumors with suspected submucosal invasion, large size, accompanying ulcers, and undifferentiated histology might have a risk of recurrence owing to micrometastasis, which would be contraindicated for EMR or ESD.