Published online Mar 14, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i10.1379

Revised: December 22, 2010

Accepted: December 29, 2010

Published online: March 14, 2011

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is an established endoscopic technique for ablating Barrett’s esophagus with high-grade dysplasia or early-stage intraepithelial neoplasia. The most common clinically significant adverse effect of PDT is esophageal stricture formation. The strictures are usually superficial and might be dilated effectively with standard endoscopic accessories, such as endoscope balloon or Savary dilators. However, multiple dilations might be required to achieve stricture resolution in some cases. We report the case of stricture that recurred after dilation with a bougie, which was completely relieved by a self-expandable metal stent.

- Citation: Cheon YK. Metal stenting to resolve post-photodynamic therapy stricture in early esophageal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(10): 1379-1382

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i10/1379.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i10.1379

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has been approved as an endoscopic treatment for Barrett’s esophagus with high-grade dysplasia, and appears to be effective in the treatment of early esophageal cancer[1-3]. The most common clinically significant adverse effect of PDT is esophageal stricture formation[2]. In some published series, > 30% of the patients treated with PDT developed esophageal strictures[3,4]. In the context of benign esophageal disease, stents have been used to seal esophageal perforations as a result of postoperative complications, endoscopic dilation procedures for achalasia[5], and those associated with dilation of post-radiation strictures[6]. Self-expandable metal stents (SEMSs) have been used for this indication.

We describe our experience with the successful resolution of an intractable post-PDT stricture using an SEMS in early esophageal cancer.

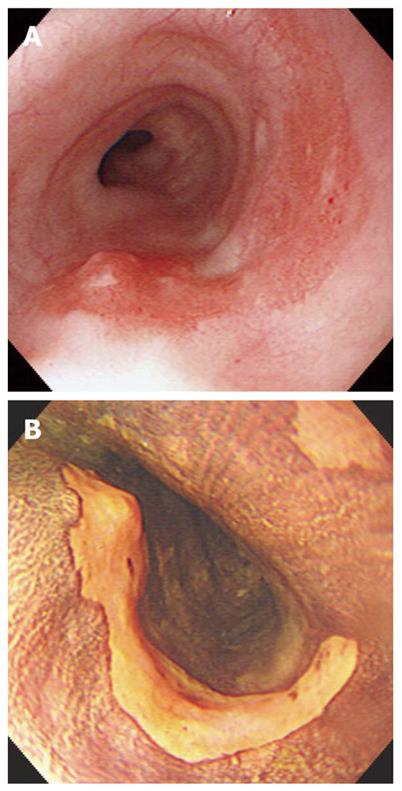

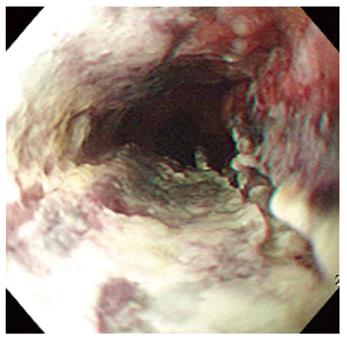

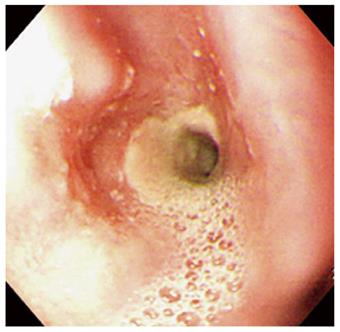

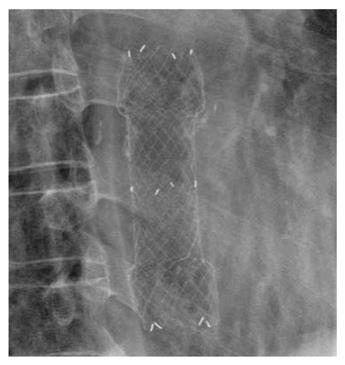

A 67-year-old man visited our hospital with dysphagia that involved solid and liquid food. Two months earlier, he had undergone PDT for early esophageal cancer. Initial endoscopy showed a flat, reddish lesion in the mid-esophagus. This lesion did not stain with Lugol’s solution (Figure 1). Endoscopic biopsy revealed squamous cell carcinoma. Chest computed tomography (CT) showed no definite distant metastasis or lymph node enlargement. The patient refused surgical treatment, therefore, PDT was performed. The patient was given porfimer sodium (Photofrin II; Axcan Pharma, Quebec, Canada) intravenously at a dose of 2 mg/kg, 48 h before endoscopic photoradiation. Light was delivered from a laser (Ceralas PDT 633; CeramOptec, Bonn, Germany) that produced 630-nm light, with an adjusted power output of 400 mW/cm, through a fiber that delivered a total energy of 180 J/cm fiber energy to the lesion. Two days after PDT, endoscopy showed circumferential coagulation necrosis with an ulcer involving the PDT-treated lesion (Figure 2). Two months after PDT, the patient complained of severe dysphagia. At that time, endoscopy showed luminal narrowing with fibrous scarring of the PDT-treated lesion (Figure 3). The patient underwent dilation three times with a Savary dilator (Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA). However, the post-PDT stricture recurred within 1 mo. Consequently, a SEMS (Choo stent, 18 mm × 100 mm; MI Tech, Seoul, Korea) was placed through the stricture site (Figure 4). Two months after stenting, we removed the stent with grasping forceps, with no complications. After removing the stent, endoscopy showed a wide opening of the previous stricture and a biopsy revealed chronic inflammation with no tumor (Figure 5).

A stricture is the most common clinically significant adverse effect of PDT[2]. Patients who develop strictures after porfimer PDT typically present with symptomatic dysphagia 3 wk after treatment. The mechanism of stricture formation after PDT with porfimer sodium is unknown. It has been hypothesized that the deep, circumferential tissue injury and resultant inflammatory reaction produced by porfimer sodium PDT induces a fibrotic response that produces structuring[4]. Other significant predictors of stricture formation are endoscopic mucosal resection before PDT, prior history of esophageal stricture, and multiple treatments of the same esophageal segment[3,7,8].

Can the incidence of post-PDT strictures be reduced or even prevented? One study has shown that the use of oral prednisone beginning at the time of PDT light delivery did not prevent development of porfimer PDT strictures[9]. One of the most important ways to prevent esophageal stricture may be to prevent circumferential mucosal injury of the esophagus during PDT.

The strictures are usually superficial and might be dilated effectively with standard endoscopic accessories, such as endoscope balloon or Savary dilators[10]. However, multiple dilations might be required to achieve stricture resolution in some cases. The clinical course of post-PDT strictures appears to differ from that of other benign esophageal strictures. In a series of patients with peptic esophageal strictures, the median number of dilations needed for complete relief of dysphagia was only one[11]. Compared with this, Prasad et al have reported that the median number of dilations for post-PDT strictures was four (range: 1-42). Another study has reported the need for multiple dilations in 11 of 34 patients[8].

To predict which type of stricture is most likely to recur and benefit from stent placement, it is important to differentiate between esophageal strictures that are simple and those that are more complex[12]. Simple esophageal strictures are focal, straight, and most have a diameter that allows passage of a normal-diameter endoscope. These strictures can successfully be treated with bougie or balloon dilation. Complex esophageal strictures are long, tortuous, or have a narrow diameter that does not allow the passage of any size of endoscope. The most common causes include caustic ingestion, anastomotic stricture, and severe peptic injury[13]. Some post-PDT strictures are complex. These strictures are more difficult to treat, requiring at least three sessions, and are associated with high recurrence rates. If these strictures cannot be dilated to an adequate diameter, recur within a short time interval, or require ongoing dilation, they are considered to be refractory. Various stent designs, both SEMSs and self-expandable plastic stent (SEPSs), have been used to dilate these types of strictures.

As the long-term clinical success rate of both SEMSs and SEPSs in refractory benign strictures is well below 50%[13], it is important to analyze which factors have played a part in these disappointing results. Factors related to long-term success were type of stricture, with post-radiation strictures being more successfully treated than peptic, anastomotic or achalasia strictures[14], and length of stricture, with shorter strictures being at lower risk of re-stricturing[15]. However, there has been no report of long-term outcome of SEMSs for post-PDT esophageal stricture.

In the present case of stricture that recurred after dilation with a bougie, a SEMS completely relieved the post-PDT stricture. The stricture has not recurred during follow-up for > 1 year. The optimal timing of stent removal has been the subject of debate. Generally, when managing benign disease, the stent should be removed within 2 mo so that late stent-related problems are avoided[15,16]. Tissue hyperproliferation at the ends of the stents represents a major limitation to long-term stent placement. Hyperplastic tissue ingrowth or overgrowth is the cause of stent-induced stricture or failure to remove a stent. Strictures that are longer or tighter require longer duration of stent placement[16,17]. However, further study is needed with a larger number of patients and long-term follow-up to demonstrate a role for SEMSs in the treatment of post-PDT esophageal stricture.

| 1. | May A, Gossner L, Pech O, Fritz A, Günter E, Mayer G, Müller H, Seitz G, Vieth M, Stolte M. Local endoscopic therapy for intraepithelial high-grade neoplasia and early adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s oesophagus: acute-phase and intermediate results of a new treatment approach. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:1085-1091. |

| 2. | Overholt BF, Panjehpour M. Photodynamic therapy for Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1997;7:207-220. |

| 3. | Overholt BF, Lightdale CJ, Wang KK, Canto MI, Burdick S, Haggitt RC, Bronner MP, Taylor SL, Grace MG, Depot M. Photodynamic therapy with porfimer sodium for ablation of high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus: international, partially blinded, randomized phase III trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:488-498. |

| 4. | Overholt BF, Panjehpour M, Haydek JM. Photodynamic therapy for Barrett’s esophagus: follow-up in 100 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:1-7. |

| 5. | Siersema PD, Homs MY, Haringsma J, Tilanus HW, Kuipers EJ. Use of large-diameter metallic stents to seal traumatic nonmalignant perforations of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:356-361. |

| 6. | Song HY, Park SI, Do YS, Yoon HK, Sung KB, Sohn KH, Min YI. Expandable metallic stent placement in patients with benign esophageal strictures: results of long-term follow-up. Radiology. 1997;203:131-136. |

| 7. | Yachimski P, Puricelli WP, Nishioka NS. Patient predictors of esophageal stricture development after photodynamic therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:302-308. |

| 8. | Prasad GA, Wang KK, Buttar NS, Wongkeesong LM, Lutzke LS, Borkenhagen LS. Predictors of stricture formation after photodynamic therapy for high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:60-66. |

| 9. | Panjehpour M, Overholt BF, Haydek JM, Lee SG. Results of photodynamic therapy for ablation of dysplasia and early cancer in Barrett’s esophagus and effect of oral steroids on stricture formation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2177-2184. |

| 10. | Overholt BF. Photodynamic therapy strictures: who is at risk? Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:67-69. |

| 11. | Saeed ZA, Ramirez FC, Hepps KS, Cole RA, Schneider FE, Ferro PS, Graham DY. An objective end point for dilation improves outcome of peptic esophageal strictures: a prospective randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:354-359. |

| 12. | Siersema PD. Treatment options for esophageal strictures. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;5:142-152. |

| 14. | Fiorini A, Fleischer D, Valero J, Israeli E, Wengrower D, Goldin E. Self-expandable metal coil stents in the treatment of benign esophageal strictures refractory to conventional therapy: a case series. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:259-262. |

| 15. | Song HY, Jung HY, Park SI, Kim SB, Lee DH, Kang SG, Il Min Y. Covered retrievable expandable nitinol stents in patients with benign esophageal strictures: initial experience. Radiology. 2000;217:551-557. |

| 16. | Kim JH, Song HY, Choi EK, Kim KR, Shin JH, Lim JO. Temporary metallic stent placement in the treatment of refractory benign esophageal strictures: results and factors associated with outcome in 55 patients. Eur Radiol. 2009;19:384-390. |

| 17. | Bakken JC, Wong Kee Song LM, de Groen PC, Baron TH. Use of a fully covered self-expandable metal stent for the treatment of benign esophageal diseases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:712-720. |

Peer reviewer: David Ian Watson, Professor, Head, Flinders University Department of Surgery, Room 3D211, Flinders Medical Center, Bedford Park, South Australia 5042, Australia

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Ma WH