Published online Mar 14, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i10.1358

Revised: January 4, 2011

Accepted: January 11, 2011

Published online: March 14, 2011

AIM: To study the clinical characteristics, diagnosis and surgical treatment of congenital bronchoesophageal fistulae in adults.

METHODS: Eleven adult cases of congenital bronchoesophageal fistula diagnosed and treated in our hospital between May 1990 and August 2010 were reviewed. Its clinical presentations, diagnostic methods, anatomic type, treatment, and follow-up were recorded.

RESULTS: Of the chief clinical presentations, nonspecific cough and sputum were found in 10 (90.9%), recurrent bouts of cough after drinking liquid food in 6 (54.6%), hemoptysis in 6 (54.6%), low fever in 4 (36.4%), and chest pain in 3 (27.3%) of the 11 cases, respectively. The duration of symptoms before diagnosis ranged 5-36.5 years. The diagnosis of congenital bronchoesophageal fistulae was established in 9 patients by barium esophagography, in 1 patient by esophagoscopy and in 1 patient by bronchoscopy, respectively. The congenital bronchoesophageal fistulae communicated with a segmental bronchus, a main bronchus, and an intermediate bronchus in 8, 2 and 1 patients, respectively. The treatment of congenital bronchoesophageal fistulae involved excision of the fistula in 10 patients or division and suturing in 1 patient. The associated lung lesion was removed in all patients. No long-term sequelae were found during the postoperative follow-up except in 1 patient with bronchial fistula who accepted reoperation before recovery.

CONCLUSION: Congenital bronchoesophageal fistula is rare in adults. Its most useful diagnostic method is esophagography. It must be treated surgically as soon as the diagnosis is established.

- Citation: Zhang BS, Zhou NK, Yu CH. Congenital bronchoesophageal fistula in adults. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(10): 1358-1361

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i10/1358.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i10.1358

Congenital bronchoesophageal fistula is usually associated with esophageal atresia and readily diagnosed in infancy. However, it may persist until adulthood if not associated with esophageal atresia. Its pathogenesis is not absolutely clear. A persistent, attachment between tracheobroncheal tree and esophagus, produced by abnormal growth of the trachea during its severance from the esophagus, has been accused for it. The chief symptoms are bouts of cough after drinking and recurrent respiratory infections. Eleven cases of congenital bronchoesophageal fistula in adults were diagnosed and operated in our hospital between May 1990 and August 2010. Its etiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentations, diagnosis, complications, and treatment were discussed for its early diagnosis.

Eleven adult cases (7 males and 4 females) of congenital bronchoesophageal fistula admitted to our hospital between 1990 and 2010 were reviewed. Their average age was 36 years (range 20-66 years) at diagnosis. Its clinical presentations, diagnostic methods, anatomic type, treatment, and follow-up were recorded.

The chief symptoms included nonspecific cough in 10 patients, recurrent bouts of cough after taking liquid food in 6 patients, hemoptysis in 6 patients, and bouts of chest pain in 3 patients, respectively. The duration of symptoms before diagnosis was 5-36.5 years and exceeded 15 years in 9 patients (Table 1).

| Symptoms | Patients (n) | Diagnosis | Patients (n) | Treatment | Patients (n) |

| Cough (nonspecific) | 10 | Esophagography | 9 | Right thoracotomy | 7 |

| Cough (after drinking) | 6 | Esophagoscopy | 1 | Left thoracotomy | 4 |

| Hemoptysis | 6 | Bronchoscopy | 1 | Resection of fistula | 10 |

| Chest pain | 3 | Division and suture | 1 | ||

| Low fever | 4 | Pleural flap insertion | 11 | ||

| Associated lobectomy | 10 | ||||

| Associated pneumonectomy | 1 |

Of the 11 patients, 3 had a history of heavy smoking, 1 had a history of tuberculosis, and 7 had no history of malignant disease, heavy smoking, tuberculosis, chest trauma, or occupational exposure to toxic agents.

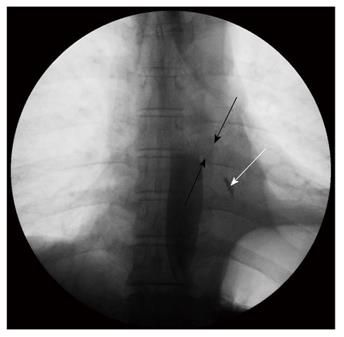

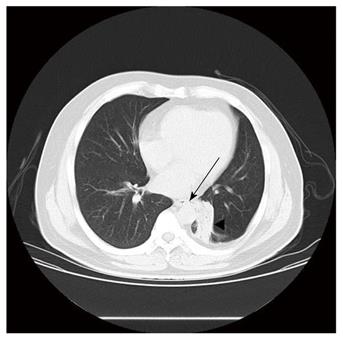

The diagnosis of congenital bronchoesophageal fistula was established by barium esophagography in 9 patients (Figure 1), by esophagoscopy in 1 patient, and by instillation of methylene blue into the esophagus during bronchoscopy in 1 patient (Table 1). Esophagoscopy showed esophageal orifice of the fistula in 7 out of 10 patients and bronchoscopy showed bronchial orifice of the fistula in 4 out of 9 patients, respectively. Preoperative chest computed tomography (CT) showed the extent of associated lung lesions (Figure 2).

The exact levels of connection between esophagus and tracheobronchial tree are listed in Table 2. The fistula was communicated with the bronchial tree on the right side in 7 patients and on the left side in 4 patients, with a segmental bronchus in 8 patients and a main or intermediate bronchus in 3 patients. The fistula communicated with the lower third of the esophagus in 9 patients and with the middle third in 2 patients.

| Anatomic types | Patients (n) |

| Lower third of esophagus | 9 |

| Main bronchus | 1 |

| Intermediate bronchus | 1 |

| Segmental bronchus | 7 |

| Middle third of esophagus | 2 |

| Main bronchus | 1 |

| Segmental bronchus | 1 |

Thoracotomy was performed from the right side in 7 patients and from the left side in 4 patients. The fistula was completely removed in 10 patients and the tract was simply divided with the end sutured in 1 patient. A pleural flap was inserted between esophagus and bronchial tree in all patients (Table 1). The associated lung lesion was removed due to sequestration, multiple epithelialized pulmonary cysts, and bronchiectasis, respectively, in 1, 6, and 4 patients (3 underwent lobectomy and 1 pneumonectomy). Extensive conglutination was found in the thorax of all patients. Large-volume bleeding (200-1000 mL) occurred during the operation, with a blood loss of over 400mL in 8 patients (Table 3).

| Blood loss(mL) | Patients(n) | Hospitalstay time | Patients(n) | Postoperative complication | Patients(n) |

| 200-400 | 3 | ≤ 2 wk | 8 | Bronchial fistula | 1 |

| 400-800 | 6 | 2 wk-1 mo | 2 | Esophageal fistula | 0 |

| 800-1000 | 2 | >1 mo | 1 | Respiratory failure | 1 |

| Circulation failure | 0 |

The postoperative course was uneventful in all patients but one who developed a bronchial fistula which was settled with conservative management and reoperation before recovery (Table 3). One patient died of chronic respiratory failure 10 years after operation.

Congenital bronchoesophageal fistula or tracheoesophageal fistula was first reported by Negus in 1929[1]. Congenital bronchoesophageal or tracheoesophageal fistula is rare in adults[2-5]. Its diagnosis is difficult due to the nonspecific nature of its symptoms. Benign bronchoesophageal fistula can remain undiagnosed for years. It was reported that bouts of cough when swallowing liquids (Ohno’s sign) are pathognomonic for this condition and present in 65% of all cases[3,4]. The duration of symptoms varies from 6 mo to 50 years before diagnosis[2,4,6,7]. The duration of symptoms in our 11 patients before diagnosis was 5-36.5 years and over 15 years in 9 patients. Of the 11 patients, 6 were misdiagnosed as multiple pulmonary cysts, 4 as bronchiectasis, and 1 as empyema, with a misdiagnosis rate of 100%. Smith[8] has given an embryologic explanation for the development of these fistulae. He stated that they are the result of persistent attachment between tracheobronchial tree and esophagus due to rapid elongation of the trachea and its separation from the esophagus.

From the pathological point of view, three points should be consider for congenital bronchoesophageal fistulae, including the long standing respiratory signs and symptoms even from infancy, the presence of bronchial or oesophageal epithelium lining the interior of the fistulous tract, and the absence of relevant inflammatory lesions in periphery of the fistula. Our 11 patients fulfilled these criteria and were therefore considered to have a congenital bronchoesophageal fistula. The fact that this type of lesions causes symptoms later in life can be explained by the occasional presence of membranes that can become permeable with time.

Conventional barium esophagography is the most sensitive means for the diagnosis of bronchoesophageal fistula[4-7,9,10]. However, it is hard to detect tiny fistulae in a single scan. Therefore, a repetitive multi-positional esophagography is helpful for improving the detection rate of bronchoesophageal fistula. In this study, congenital bronchoesophageal fistulae were found in 6 cases during the first scan, and tiny fistulae were found in 3 cases during the multi-positional esophagography, indicating that both bronchoscopy and esophagoscopy should be performed in these cases because they cannot always demonstrate the fistulous orifice. However, they help us to choose the modus operandi[2,4-7]. CT scanning can rule out the presence of neoplasm and adenopathy, and define the extent of coexisting pulmonary disease, which may need resection[5,7,11].

Braimbridge et al[12] have classified congenital bronchoesophageal fistula into 4 types (Table 4). Type II is the most prevalent and comprises almost 90% of all cases in some series[2]. In our series, typesI- IV were found in 2, 7, 2, and 1 cases, respectively, with an associated lung sequestration.

| TypeI | Congenital bronchoesophageal fistula associated with congenital oesophageal diverticulum |

| Type II | Simple bronchoesophageal fistula |

| Type III | Bronchoesophageal fistula with an intralobar cyst |

| Type IV | Bronchoesophageal fistula communicating with a pulmonary sequestration |

Despite the benign nature of this disease, it may lead to fatal complications if untreated[5,7,13]. In order to avoid distal pulmonary lesions, early diagnosis and treatment are important. A high index of suspicion should be borne in mind for patients with repeated pulmonary infections or with coughing spells associated with ingestion.

Thoracotomy is the traditional treatment procedure for most cases of fistula[2,4,6,7]. The two main treatment procedures are division and suturing of the ends of fistula and complete resection. The insertion of a muscular or pleural flap can prevent any refistulization[4,7,9,13]. Pulmonary resection is often needed in patients with coexistent pulmonary diseases such as bronchiectasis and recurrent pneumonitis. In our series, fistula and associated lung lesions were completely removed in 10 patients, and the ends of fistula were sutured in 1 patient. The prognosis of the patients was excellent after the procedure. The postoperative course was uneventful in all patients but one who was complicated by bronchial fistula due to intraoperative contamination of the pleural space by oesophageal materials. However, the patient recovered after treatment. The less effective treatment modality is occlusion of the esophageal opening with biologic glue or a Celestin tube[14], or with sodium hydroxid and acetic acid solution via a bronchoscope or an esophagoscope[15]. We believe these techniques should be considered only when the condition of patients does not allow a thoracotomy.

Currently, most studies concerning congenital bronchoesophageal fistula in adults are case reports, and few clinical data are available based on large samples. In this study, 11 cases of congenital bronchoesophageal fistula admitted to our hospital in recent 20 years were analyzed.

In conclusion, a high index of suspicion should be borne in mind for patients with repeated pulmonary infections, especially with symptoms of recurrent bouts of cough after taking liquid food. Conventional barium esophagography is presently the most sensitive means for the diagnosis of congenital bronchoesophageal fistula. However, multi-positional esophagography should be performed for tiny or horizontal fistulae. Due to the long duration before diagnosis and repeated pulmonary infections, patients often suffer from severe conglutination in the thorax. A large volume bleeding may occur during operation and adequate blood preparation is necessary. Surgical management is the vital point for the prognosis of patients with congenital bronchoesophageal fistula. Fistula and associated lung lesions shall be completely removed to avoid recrudescence.

Congenital bronchoesophageal or tracheoesophageal fistula is rare in adults. Its diagnosis is difficult due to the nonspecific nature of its symptoms.

The clinical characteristics, diagnosis and surgical treatment of congenital bronchoesophageal fistulae in adults were investigated.

Currently, most studies concerning congenital bronchoesophageal fistula in adults are case reports, and few clinical data are available based on large samples. In this study, 11 cases of congenital bronchoesophageal fistula admitted to hospital in recent 20 years were analyzed.

This is an interesting case series report on a difficult and often misunderstood clinical condition.

| 1. | Azoulay D, Regnard JF, Magdeleinat P, Diamond T, Rojas-Miranda A, Levasseur P. Congenital respiratory-esophageal fistula in the adult. Report of nine cases and review of the literature. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1992;104:381-384. |

| 2. | Su L, Wei XQ, Zhi XY, Xu QS, Ma T. Congenital bronchoesophageal fistula in an adult: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3776-3777. |

| 3. | Linnane BM, Canny G. Congenital broncho-esophageal fistula: A case report. Respir Med. 2006;100:1855-1857. |

| 4. | Kim JH, Park KH, Sung SW, Rho JR. Congenital bronchoesophageal fistulas in adult patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:151-155. |

| 5. | Rämö OJ, Salo JA, Mattila SP. Congenital bronchoesophageal fistula in the adult. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;59:887-889; discussion 890. |

| 6. | Lazopoulos G, Kotoulas C, Lioulias A. Congenital bronchoesophageal fistula in the adult. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1999;16:667-669. |

| 7. | Aguiló R, Minguella J, Jimeno J, Puig S, Galeras JA, Gayete A, Sánchez-Ortega JM. Congenital bronchoesophageal fistula in an adult woman. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:916-917. |

| 8. | Smith DC. A congenital broncho-oesophageal fistula presenting in adult life without pulmonary infection. Br J Surg. 1970;57:398-400. |

| 9. | Chiu HH, Chen CM, Mo LR, Chao TJ. Gastrointestinal: Tuberculous bronchoesophageal fistula. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1074. |

| 10. | Ford MA, Mueller PS, Morgenthaler TI. Bronchoesophageal fistula due to broncholithiasis: a case series. Respir Med. 2005;99:830-835. |

| 11. | Nagata K, Kamio Y, Ichikawa T, Kadokura M, Kitami A, Endo S, Inoue H, Kudo SE. Congenital tracheoesophageal fistula successfully diagnosed by CT esophagography. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:1476-1478. |

Peer reviewer: Luigi Bonavina, Professor, Department of Surgery, Policlinico San Donato, University of Milano,

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Ma WH