Published online Mar 14, 2011. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i10.1326

Revised: November 25, 2010

Accepted: December 2, 2010

Published online: March 14, 2011

AIM: To characterize the effects of age on the mechanisms underlying the common condition of esophageal dysphagia in older patients, using detailed manometric analysis.

METHODS: A retrospective case-control audit was performed on 19 patients aged ≥ 80 years (mean age 85 ± 0.7 year) who underwent a manometric study for dysphagia (2004-2009). Data were compared with 19 younger dysphagic patients (32 ± 1.7 years). Detailed manometric analysis performed prospectively included basal lower esophageal sphincter pressure (BLESP), pre-swallow and nadir LESP, esophageal body pressures and peristaltic duration, during water swallows (5 mL) in right lateral (RL) and upright (UR) postures and with solids. Data are mean ± SE; a P-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS: Elderly dysphagic patients had higher BLESP than younger patients (23.4 ± 3.8 vs 14.9 ± 1.2 mmHg; P < 0.05). Pre-swallow LESP was elevated in the elderly in both postures (RL: 1 and 4 s P = 0.019 and P = 0.05; UR: P < 0.05 and P = 0.05) and solids (P < 0.01). In older patients, LES nadir pressure was higher with liquids (RL: 2.3 ± 0.6 mmHg vs 0.7 ± 0.6 mmHg, P < 0.05; UR: 3.5 ± 0.9 mmHg vs 1.6 ± 0.5 mmHg, P = 0.01) with shorter relaxation after solids (7.9 ± 1.5 s vs 9.7 ± 0.4 s, P = 0.05). No age-related differences were seen in esophageal body pressures or peristalsis duration.

CONCLUSION: Basal LES pressure is elevated and swallow-induced relaxation impaired in elderly dysphagic patients. Its contribution to dysphagia and the effects of healthy ageing require further investigation.

- Citation: Besanko LK, Burgstad CM, Mountifield R, Andrews JM, Heddle R, Checklin H, Fraser RJ. Lower esophageal sphincter relaxation is impaired in older patients with dysphagia. World J Gastroenterol 2011; 17(10): 1326-1331

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v17/i10/1326.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v17.i10.1326

Dysphagia is common in older individuals, with mealtime difficulties being reported in 87% of residential care clients who are predominantly elderly[1]. This condition is associated with significant morbidity (anxiety and depression) and, in some cases, increased mortality from malnutrition and aspiration pneumonia[2]. People aged over 65 years constitute more than 15% of the South Australian population and this proportion is predicted to increase substantially over the next 10 years[3]. Moreover, this demographic trend is consistently noted across the developed world. There is thus the need for a greater understanding of the pathophysiology of dysphagia in older individuals.

An increase in esophageal motor abnormalities has been reported with advancing age[4]. Studies in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease suggest that only 62% of swallows are normal in subjects aged over 64 years, compared with 95% of younger patients[5]. Despite the magnitude of this clinical problem in the elderly, no studies have detected significant differences in the mechanism of esophageal dysphagia between age groups, although older patients tend to find dysphagia more clinically troublesome[6].

In the absence of a structural esophageal lesion, more than 50% of all patients with dysphagia have abnormal motility on manometry[7]. However, the most common diagnosis made after investigation is non-specific esophageal motility disorder (NSMD). This is a “default position” when esophageal motor function is abnormal, but does not satisfy the diagnostic features of classic motility disorders, such as diffuse esophageal spasm or achalasia. Advances in high resolution manometry have improved the ability to identify the specific motility changes underlying such conditions[8], which has significantly improved treatment and patient outcomes[8,9]. However, the absence of a clearly understood pathogenic mechanism for dysphagia in older adults currently limits the provision of specific therapeutic recommendations for these patients.

Much of our current understanding of the effects of aging on esophageal physiology is based on data from healthy older individuals without dysphagia. These studies have shown age-related esophageal motility changes that include decreased upper esophageal sphincter pressure with reduced duration of relaxation[10], low amplitude peristalsis and increased stiffness of the esophageal body[11]. Changes in lower esophageal sphincter function, however, have been harder to identify in healthy ageing[12] and studies are rarely performed in adults above the age of 80 years. Alterations that may occur with extreme age are increasingly relevant as the proportion of the population surviving into their ninth decade increases.

The few studies looking specifically at esophageal motor function in symptomatic older patients have yielded conflicting results, but do not appear to support an earlier concept of “presbyesophagus”. This refers to a cluster of dysfunctions, including decreased contractile activity, polyphasic waves in the esophageal body and incomplete relaxation with esophageal dilatation[13]. Although no differences in broad diagnostic category have been demonstrated between older and younger dysphagic patients[6,14], we hypothesize that older individuals may comprise a distinct subgroup of NSMD. The pathophysiologic abnormalities in these patients may involve more subtle motor sequencing problems that are not readily detected using standard manometry. Recognition of such abnormal motor patterns would improve understanding of the effects of ageing on the esophagus, as well as potentially provide a more targeted approach to treatment for the increasing number of older individuals with dysphagia.

The aim of the current study, therefore, was to compare esophageal motility between older (> 80 years) and younger adults with dysphagia, using analysis of high resolution manometric data.

Subjects were identified from a prospectively collected database at the Repatriation General Hospital, Daw Park, a tertiary referral centre providing an esophageal manometry service to an ageing predominantly veteran population along with younger public hospital patients. Esophageal manometric studies were performed on patients presenting with a variety of symptoms suggestive of disease, including dysphagia, atypical chest pain, heartburn and cough. Of these, the database was audited to identify all patients aged ≥ 80 years investigated for dysphagia (as their primary symptom) between January 2004 and November 2009. These were gender-matched to a group of younger dysphagic patients. Exclusion criteria included (1) incomplete manometric data; (2) diagnosis of achalasia; (3) previous fundoplication; and (4) diabetes mellitus.

The standard manometric diagnoses as provided to the referring physician, and symptoms of older and younger dysphagic patients from this database have previously been reported in a clinical audit[6]. The current study, however, provides a more specific evaluation of the possible motor mechanisms underlying dysphagia, with a detailed re-analysis of the previous manometric data.

The manometry database of this laboratory was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Repatriation General Hospital. All subjects provided written informed consent prior to the inclusion of their results in the database.

While all patients included in the study described dysphagia, each patient was asked to report whether it was present with solids, liquids or both and whether it was at the level of upper, mid or lower esophagus. These data were recorded prior to performing their esophageal manometry investigation.

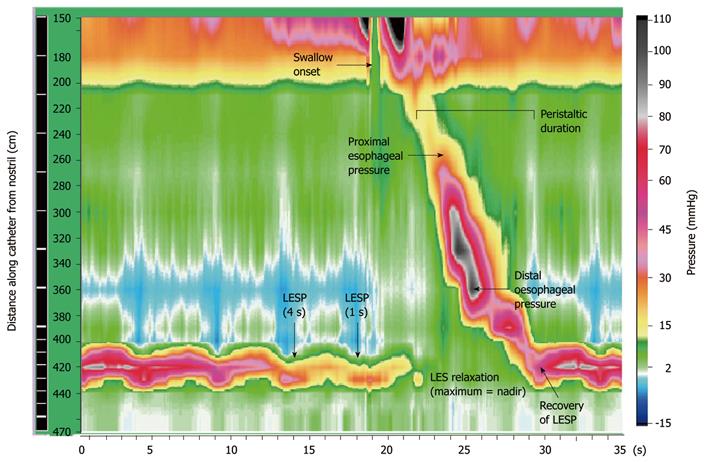

Esophageal pressures were measured using high resolution manometry (HRM). This technique allows visualization of esophageal contractility as a continuum of pressure and time (Figure 1) using a colour display. To achieve this, pressure sensors were spaced at close intervals (1-3 cm apart) and at multiple recording sites, enabling extrapolation of pressure values between sensors without loss of accuracy. Compared to conventional manometry, HRM has several technical advantages that include greater efficiency, higher quality recordings and more objective interpretation. Intraluminal pressures were measured using a 16 channel silicone-rubber manometric assembly (Dentsleeve International, Toronto, Canada). The 9 most proximal side-holes (channels 1-9) were spaced 3 cm apart and spanned the pharynx and esophageal body (24 cm). The remaining 7 side-holes (channels 10-16) were spaced at 1 cm intervals and positioned astride the LES, with the most distal channel in the proximal stomach. All lumina were perfused with degassed distilled water at a rate of 0.15 mL/min using a low compliance perfusion pump (Dentsleeve International, Ontario Canada). Data were recorded at 25Hz and analyzed using specialized software (Trace Version 1.2v, Hebbard, Melbourne, Australia). All pressures were referenced to the intra-gastric pressure and could be displayed as a spatio-temporal color plot or conventional line-plot.

All studies were performed after a minimum 4-h fast. The manometric assembly was passed transnasally into the stomach, via an anaesthetized nostril. Subjects were placed in the right lateral (RL) posture and allowed time to adapt to the assembly. A basal lower esophageal sphincter pressure (BLESP) was recorded for 30 s. Ten 5 mL liquid (water) swallows were performed in the RL posture, and repeated seated upright (UR). Manometry was also recorded during 5 standardized solid boluses (1/8 sliced white bread with crust removed) in the UR position. Subjects were asked to chew the bread and indicate when they were ready to swallow. The presence or absence of dysphagia was recorded for each swallow.

The original clinical manometry recordings were re-analyzed manually by 2 observers (LB and CB), neither of whom was responsible for the initial report. Both observers were blinded to patient age, gender and initial manometric diagnosis. Detailed motility analysis was performed, comprising (1) BLESP at end-expiration; (2) LESP at 1 and 4 s before the onset of each swallow; (3) number of successful LES relaxations (defined as > 75% reduction in LESP); (4) nadir LESP (point of most complete LES relaxation) and time to nadir; (5) time to recovery of LES tone after swallow-induced relaxation; (6) amplitude of proximal and distal esophageal pressures (measured 6 cm below the upper esophageal sphincter and 4 cm above the LES, respectively); and (7) duration of peristalsis (time between peak amplitudes of channels 1-9). The sites at which esophageal pressure measurements were taken are shown in Figure 1. Subjects were excluded if more than 30% of their manometric data were missing, or more than 30% double swallows were encountered.

All data are expressed as a mean ± SE. Manometric parameters were compared between groups using Student unpaired t-test (two-tailed). A P-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Nineteen patients aged older than 80 years (9 male, 10 female; mean age 85 ± 0.7 year) were included. The pattern of dysphagia was characterised as upper (21%), mid (42%) or lower (37%) esophagus, present with solids (47%), liquids (6%) or both (47%). Data were compared to 19 younger patients (9 male, 10 female; mean age 32 ± 1.7 years) with esophageal dysphagia in the upper (48%), mid (26%) or lower (26%) esophagus, with solids (79%), liquids (10%) or both (11%).

Mean basal LESP was higher in the older patients (23.4 ± 3.8 mmHg) compared to younger dysphagic patients (14.9 ± 1.2 mmHg) (P < 0.05).

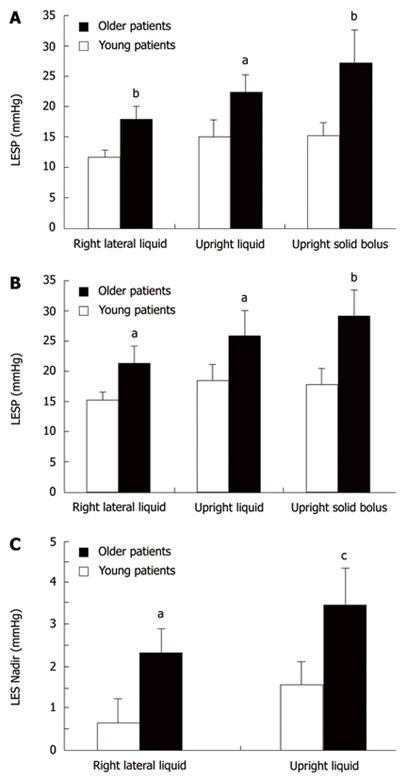

Pre-swallow LESP was higher in older dysphagic patients in both RL (elderly vs young; 1 s: 17.8 ± 2.2 mmHg vs 11.6 ± 1.2 mmHg, P = 0.019; and 4 s: 21.3 ± 2.8 mmHg vs 15.3 ± 1.3 mmHg, P = 0.05) and UR (1 s: 22.3 ± 2.9 mmHg vs 14.9 ± 2.9 mmHg, P < 0.05; and 4 s: 25.9 ± 4.2 mmHg vs 18.3 ± 2.7 mmHg, P = 0.05) postures, and with solid boluses (1 s: 27.3 ± 5.5 mmHg vs 15.2 ± 2.2 mmHg, and 4 s: 29.1 ± 4.2 mmHg vs 17.7 ± 2.8 mmHg, P < 0.01 for both) (Figure 2A and B).

Mean nadir LESP was higher in older patients with liquid swallows in both RL (2.3 ± 0.6 mmHg vs 0.7 ± 0.6 mmHg, P < 0.05) and upright (3.5 ± 0.9 mmHg vs 1.6 ± 0.5 mmHg, P = 0.01) postures, when compared to younger patients (Figure 2C). There were no differences in nadir pressure with solids, time to nadir, or number of complete LES relaxations, between age groups.

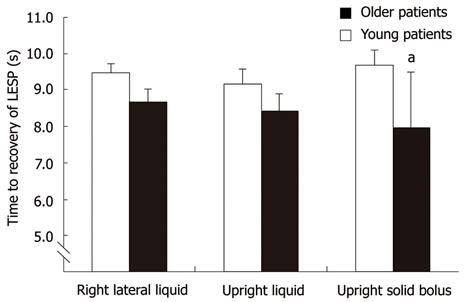

Time to recovery of LES tone after swallow-induced relaxation was shorter in the older group after a solid bolus (P = 0.05), with a similar trend with liquid swallows in the RL posture (P = 0.07) (Figure 3).

There were no significant differences between age groups in mean amplitude of proximal or distal esophageal body contractions with liquids or solids (Table 1).

| Right Lateral water | Upright water | Upright solids | |

| Older | |||

| Proximal | 39.1 ± 7.3 | 41.4 ± 5.7 | 45.2 ± 7.5 |

| Distal | 53.8 ± 7.8 | 67.3 ± 16.4 | 61.7 ± 14.8 |

| Young | |||

| Proximal | 27.9 ± 3.0 | 29.6 ± 3.9 | 35.7 ± 3.1 |

| Distal | 62.3 ± 6.0 | 55.5 ± 6.8 | 57.9 ± 8.1 |

The duration of esophageal peristalsis was similar between age groups with liquid swallows in both postures (older vs young patients; RL 8.5 ± 0.5 s vs 8.6 ± 0.3 s; UR 8.9 ± 0.8 s vs 8.0 ± 0.3 s), and with solid boluses (9.4 ± 1.7 s vs 8.3 ± 0.5 s).

This study is the first to evaluate motility changes specific to dysphagia in the elderly. It demonstrates subtle differences in LES function between older and younger patients with dysphagia. In particular, increased age was associated with a higher resting pressure, incomplete relaxation and a shorter time to recovery of tone after swallowing. There were, however, no differences in esophageal body pressures or peristaltic duration between age groups. These findings of LES dysfunction provide new insights into the possible mechanisms underlying dysphagia in elderly patients.

Using standard clinical manometric analysis, previous studies reported no differences in the frequency of diagnostic categories between older and younger subjects with dysphagia[6,14]. This suggests consistency amongst regular reporters of these clinical studies. However, the current study demonstrates specific motility differences between age groups using a more detailed approach to analysis. In agreement with Pandolfino et al[15], these data suggest that standard manometric assessment may not be sufficiently sensitive to detect potentially relevant abnormalities.

Adequate LES relaxation is pivotal in allowing bolus transit across the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ); this is both intuitive and demonstrated in physiologic and mechanical studies of esophageal emptying[16]. Studies in patients with achalasia[17-19] or post-fundoplication[20,21] confirm the functional consequence of inadequate LES relaxation. Therapeutic modalities aimed at reducing sphincter pressure and thus enhancing bolus clearance are known to reduce dysphagia in these patients[22,23]. These findings support the concept that high LES nadir pressure and incomplete relaxation observed in elderly patients could impede bolus clearance, and may be directly relevant to the production of their dysphagia.

Increased basal LES pressure observed in our elderly patients did not meet current criteria used to define Hypertensive LES (HLES) syndrome (mean LESP > 45 mmHg)[24]. However, we postulate that subtle increases in LESP, in combination with failure to relax adequately, may contribute to their dysphagia. Gockel et al demonstrated an association between elevated resting LESP and dysphagia in 100 patients with HLES (defined as BLESP > 26 mmHg). Of these, 71% of subjects reported moderate dysphagia in the absence of any other motility disorder[25]. There is, however, inconsistency in dysphagia rates between studies, and the pathophysiology and clinical significance of this are uncertain[24,26,27]. It has also been reported in HLES patients that LES nadir pressure is higher than that seen in healthy subjects, with a shorter relaxation duration[25,26]. Similar dynamics of the LES were observed in the elderly patients of the current study.

Disturbances in the activation of vagal pathways to the LES (in particular nitric oxide release) underlie impaired sphincter relaxation in motility disorders such as achalasia[28]. A loss of vagal motor control of the LES has not yet been studied in older patients with dysphagia, however it is known that ageing is associated with degeneration of inhibitory ganglion cells in the intramural esophageal plexus[29,30]. A significant reduction in the number of neurons innervating the LES leads to increased basal pressure and poor relaxation[31]. If this age-associated neuronal loss occurs to a pathologic extent, it may produce dysphagia in a subset of older people. Another possibility may be decreased LES compliance, reflecting either changes in the characteristics of the circular muscle or adjacent anatomic structures. Specifically, this may include the crural fibres of the diaphragm and, in some patients, compression due to ectasia of the descending aorta; however further investigation is required.

Adequate propagation and strength of distal esophageal pressures are pivotal in efficient bolus clearance. Studies using impedance and fluoroscopic techniques have both confirmed that a minimum contractile amplitude of 30 mmHg in the distal esophagus is required for sufficient flow across the GEJ[32,33]. In patients with hypertensive LES, Gockel et al[25] showed that a quarter of subjects generated pressures in the distal esophagus above 180 mmHg, which is consistent with “nutcracker esophagus”. Previous data regarding the physiologic effect of ageing on esophageal body function, however, suggests an expected decrease in peristaltic amplitude in healthy older people. In the current study, distal esophageal amplitudes in elderly patients with dysphagia were similar to those of younger patients, despite a higher basal LES pressure and impaired LES relaxation. This failure to compensate for increased resistance at the GEJ may further contribute to their symptoms.

In conclusion, these data indicate that subtle impairment of LES relaxation, and thus increased resistance at the GEJ, is a potential contributor to dysphagia in elderly patients. This may reflect the normal ageing process or the pathogenesis of dysphagia, and warrants further study. As there are limited data on LES function in healthy asymptomatic elderly subjects, detailed examination of this area may be of benefit.

Esophageal dysphagia is common in older individuals and adversely affects both morbidity and mortality. Previous studies have shown changes in esophageal function with advancing age. However, data on the specific mechanisms underlying dysphagia in older patients have yielded conflicting results. A better understanding of the pathophysiology in this group would enable a more targeted approach to treatment.

Much of our current understanding on esophageal motor abnormalities reported with advancing age is based on data from asymptomatic older individuals. In over 50% of patients with dysphagia, abnormal esophageal motility is seen on manometry. However, no specific differences in the mechanism underlying dysphagia in older patients have been identified. In this study, the authors demonstrate subtle differences in lower esophageal sphincter (LES) function in elderly dysphagic patients using a detailed manometric approach. These findings provide new insights into the possible mechanisms underlying dysphagia in this patient group.

The few studies examining esophageal motor function in older patients with dysphagia provide conflicting data. Recent studies do not support an earlier concept that age-related changes (presbyesophagus) are responsible for symptoms. Broad manometric diagnoses are similar between age-groups, although it is possible that elderly patients comprise a distinct sub-group of non-specific motility disorders. In the current study, LES basal pressure was elevated and relaxation impaired in elderly patients. A possible etiology may be degeneration of neurons innervating the LES, which has been described with ageing.

There is a need for a greater understanding of esophageal motor changes that are specific to older patients with dysphagia. The absence of a clearly understood pathogenic mechanism in this group currently limits the provision of specific therapeutic recommendations.

High resolution manometry is a methodology that improves visualization of esophageal contractility. Intraluminal pressures are displayed as a colour plot over time, using multiple closely spaced pressure sensors (time on x-axis and location of sensors on y-axis). Pressure values between sensors are extrapolated and amplitudes displayed as different colours in the plot.

In this manuscript, Besanko et al compared esophageal motility between older and younger adults with dysphagia using high resolution manometric data analysis. The trial is carefully performed and clinically important.

Peer reviewer: Hirotada Akiho, MD, PhD, Department of Medicine and Bioregulatory Science, Graduate school of Medical Sciences, Kyushu University, 3-1-1 Maidashi, Higashi-ku, Fukuoka 812-8582, Japan

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Ma WH

| 1. | Steele CM, Greenwood C, Ens I, Robertson C, Seidman-Carlson R. Mealtime difficulties in a home for the aged: not just dysphagia. Dysphagia. 1997;12:43-50; discussion 51. |

| 2. | Eslick GD, Talley NJ. Dysphagia: epidemiology, risk factors and impact on quality of life--a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:971-979. |

| 3. | Statistics ABo. Census of Population and Housing 2006. . |

| 4. | Andrews JM, Heddle R, Hebbard GS, Checklin H, Besanko L, Fraser RJ. Age and gender affect likely manometric diagnosis: Audit of a tertiary referral hospital clinical esophageal manometry service. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:125-128. |

| 5. | Achem AC, Achem SR, Stark ME, DeVault KR. Failure of esophageal peristalsis in older patients: association with esophageal acid exposure. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:35-39. |

| 6. | Andrews JM, Fraser RJ, Heddle R, Hebbard G, Checklin H. Is esophageal dysphagia in the extreme elderly (≥ 80 years) different to dysphagia younger adults? A clinical motility service audit. Dis Esophagus. 2008;21:656-659. |

| 7. | Katz PO, Dalton CB, Richter JE, Wu WC, Castell DO. Esophageal testing of patients with noncardiac chest pain or dysphagia. Results of three years’ experience with 1161 patients. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:593-597. |

| 8. | Kahrilas PJ. Esophageal motor disorders in terms of high-resolution esophageal pressure topography: what has changed? Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:981-987. |

| 9. | Pandolfino JE, Kwiatek MA, Nealis T, Bulsiewicz W, Post J, Kahrilas PJ. Achalasia: a new clinically relevant classification by high-resolution manometry. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1526-1533. |

| 10. | Wilson JA, Pryde A, Macintyre CC, Maran AG, Heading RC. The effects of age, sex, and smoking on normal pharyngoesophageal motility. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:686-691. |

| 11. | Gregersen H, Pedersen J, Drewes AM. Deterioration of muscle function in the human esophagus with age. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:3065-3070. |

| 12. | Micklefield GH, May B. [Manometric studies of the esophagus in healthy subjects of different age groups]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1993;118:1549-1554. |

| 13. | Soergel KH, Zboralske FF, Amberg JR. Presbyesophagus: esophageal motility in nonagenarians. J Clin Invest. 1964;43:1472-1479. |

| 14. | Robson KM, Glick ME. Dysphagia and advancing age: are manometric abnormalities more common in older patients? Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:1709-1712. |

| 15. | Pandolfino JE, Fox MR, Bredenoord AJ, Kahrilas PJ. High-resolution manometry in clinical practice: utilizing pressure topography to classify oesophageal motility abnormalities. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:796-806. |

| 16. | Brasseur JG, Nicosia MA, Pal A, Miller LS. Function of longitudinal vs circular muscle fibers in esophageal peristalsis, deduced with mathematical modeling. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1335-1346. |

| 17. | Lake JM, Wong RK. Review article: the management of achalasia - a comparison of different treatment modalities. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:909-918. |

| 18. | Park W, Vaezi MF. Etiology and pathogenesis of achalasia: the current understanding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1404-1414. |

| 19. | Tatum RP, Wong JA, Figueredo EJ, Martin V, Oelschlager BK. Return of esophageal function after treatment for achalasia as determined by impedance-manometry. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1403-1409. |

| 20. | Breumelhof R, Fellinger HW, Vlasblom V, Jansen A, Smout AJ. Dysphagia after Nissen fundoplication. Dysphagia. 1991;6:6-10. |

| 21. | Hunter JG, Swanstrom L, Waring JP. Dysphagia after laparoscopic antireflux surgery. The impact of operative technique. Ann Surg. 1996;224:51-57. |

| 22. | Finley RJ, Rattenberry J, Clifton JC, Finley CJ, Yee J. Practical approaches to the surgical management of achalasia. Am Surg. 2008;74:97-102. |

| 23. | Richter JE. Modern management of achalasia. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2005;8:275-283. |

| 24. | Waterman DC, Dalton CB, Ott DJ, Castell JA, Bradley LA, Castell DO, Richter JE. Hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter: what does it mean? J Clin Gastroenterol. 1989;11:139-146. |

| 25. | Gockel I, Lord RV, Bremner CG, Crookes PF, Hamrah P, DeMeester TR. The hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter: a motility disorder with manometric features of outflow obstruction. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:692-700. |

| 26. | Freidin N, Traube M, Mittal RK, McCallum RW. The hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter. Manometric and clinical aspects. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:1063-1067. |

| 27. | Graham DY. Hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter: a reappraisal. South Med J. 1978;71 Suppl 1:31-37. |

| 28. | Walzer N, Hirano I. Achalasia. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37:807-825, VIII. |

| 29. | Blechman MB, Gelb AM. Aging and gastrointestinal physiology. Clin Geriatr Med. 1999;15:429-438. |

| 30. | Firth M, Prather CM. Gastrointestinal motility problems in the elderly patient. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1688-1700. |

| 31. | Hashemi N, Banwait KS, DiMarino AJ, Cohen S. Manometric evaluation of achalasia in the elderly. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:431-434. |

| 32. | Kahrilas PJ, Dodds WJ, Hogan WJ. Effect of peristaltic dysfunction on esophageal volume clearance. Gastroenterology. 1988;94:73-80. |

| 33. | Nguyen NQ, Tippett M, Smout AJ, Holloway RH. Relationship between pressure wave amplitude and esophageal bolus clearance assessed by combined manometry and multichannel intraluminal impedance measurement. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2476-2484. |