Published online Mar 7, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i9.1161

Revised: December 27, 2009

Accepted: January 3, 2010

Published online: March 7, 2010

We describe simultaneous surgery performed on a 71-year-old woman with critical aortic stenosis and gastric cancer that were diagnosed at the same time. The patient qualified for simultaneous surgery for both these diseases. Good early outcome was achieved. There is a lack of standards for treatment of patients with coexistence of two life-threatening conditions. We discuss surgical tactics and potential benefits of such management.

- Citation: Zielinski J, Jaworski R, Pawlaczyk R, Swierblewski M, Kabata P, Jaskiewicz J, Rogowski J. Simultaneous surgery for critical aortic stenosis and gastric cancer: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(9): 1161-1164

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i9/1161.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i9.1161

Cardiovascular and neoplastic diseases are the main causes of death in Europe. Aortic stenosis is currently the third most common heart disease in Europe and North America. It is mainly caused by degenerative processes, with secondary calcification of the valve. Moderate stenosis is observed in 5% of the population over the age of 75 years, while critical stenosis occurs in 3% of the population, with half of these cases being asymptomatic. Diagnosis is based on preoperative echocardiographic examination. Severe stenosis can be managed with one of the following procedures: valve replacement, transcatheter aortic valve implantation or, in some cases, percutaneous valvulotomy with Inoue balloon[1].

Gastric cancer remains one of the most common neoplastic diseases in the world, with fourth highest morbidity. Diagnosis is based on pathologic examination of a specimen obtained at gastroscopy. Infiltration depth is evaluated with endoscopic ultrasound. Computed tomography (CT) enables assessment of regional lymph nodes and presence of remote metastases[2]. Surgical treatment remains a therapy of choice for gastric cancer; however there are no standard procedures. In Europe, 5-year survival following R0 gastric resection is 33%-35%[3].

We present the following case of a patient who underwent simultaneous surgical treatment of gastric cancer and asymptomatic critical aortic stenosis.

A 71-year-old female patient (weight 56 kg, height 164 cm) was admitted to the Department of Surgical Oncology because of gastric tumor. She had a history of non-specific epigastric pain and appetite loss for the past 2 mo. Weight loss was 12 kg over 6 mo. Laboratory tests revealed secondary anemia (Hb 10.8 g/dL) and lowered blood ferritin level (5 ng/mL). The patient had a history of melena and loose stool prior to admission to the hospital. She had never been treated for gastrointestinal tract diseases.

Because of non-specific abdominal symptoms and anemia, the patient was referred for endoscopic examination of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Gastroscopy revealed an ulcerated tumor in the upper third of the gastric corpus, reaching over half of its circumference. Pathologic examination of the biopsy specimen revealed gastric adenocarcinoma (adenocarcinoma tubulare G1 exulcerans, intestinal type according to Lauren’s classification). Before admission, the patient had never been treated for cardiac or vascular diseases. Cardiac efficiency was classified grade II NYHA (New York Heart Association) scale[4]. The patient had a history of decreased arterial blood pressure over the past 10 years.

At the age of 38 years, the patient was diagnosed with primary adrenal insufficiency (Addison’s disease), treated with hydrocortisone (30 mg orally). One year before admission, after bone marrow biopsy and laboratory findings, the patient was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, requiring only regular control in the hematology out-patient clinic.

At the age of 50 years, the patient underwent two surgeries: left thyroid lobectomy because of nodular goiter (currently in euthyreosis) and left breast amputation because of breast cancer (currently under oncological observation). Allergic history comprised of a pollen allergy.

Electrocardiogram examination revealed regular sinus rhythm with heart rate 71 bpm, PR 156 ms, QT 390 ms, QTc 0.45 ms. Chest X-ray did not show any lung pathology. Sclerotic aorta with typical poststenotic dilation of ascending aorta and hypertrophy of left ventricle were described. Echocardiographic examination revealed critical aortic stenosis with maximal transvalvular pressure gradient of 135 mmHg; mean gradient was 95 mmHg. Valve surface area was estimated to be 0.3 cm2. Interventricular septum diameter was 16 mm, and left ventricular ejection fraction was 45%-50%. Additionally, significant calcification of the aortic bulb and aortic valve cusps was found. Subsequently, a coronarography was performed, which showed no significant stenosis in the coronary vessels.

No enlarged lymph nodes in the posterior mediastinum were observed on thoracic CT. On the other hand, on abdominal CT numerous non-characteristic enlarged lymph nodes were observed in the retroperitoneum along the abdominal aorta. This included enlarged lymph nodes surrounding the celiac trunk and in the mesentery of the small intestine. It was not clear, however, whether lymphadenopathy resulted from the chronic lymphocytic leukemia or from metastases of the gastric cancer.

Additionally, gallstones 24 mm in size were found. An anterior gastric wall thickening in the region of lesser curvature was observed. In view of the clinical examination and the results of image studies the patient was classified as having no sign of metastatic disease. During preoperative diagnostic staging, laparoscopy was considered among other available procedures, however, after presenting the case to cardiac surgeons and anesthesiologists, this was called off due to the relatively high risk of sudden cardiac death[4].

Anesthesiologist consultation assessed the patient’s cardiac efficiency as grade II NYHA (New York Heart Association) scale and grade III ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) physical status classification[5,6].

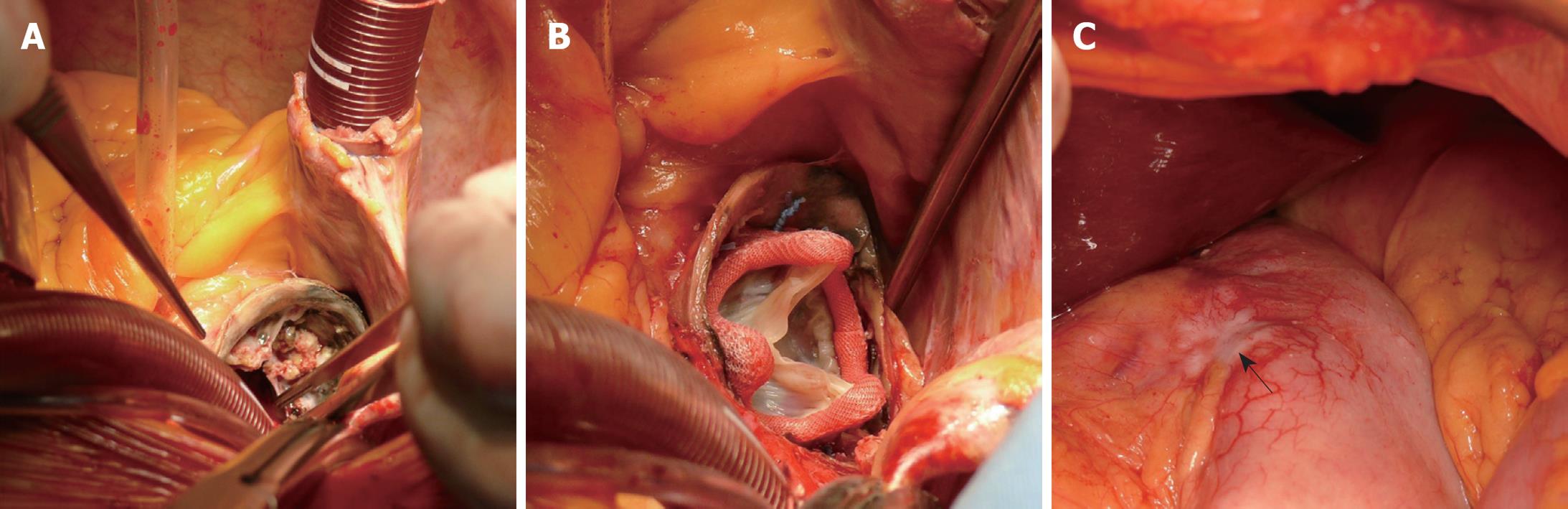

The operation was performed via sternotomy and median laparotomy by two surgical teams. There were some doubts about operability of the stomach cancer, therefore the oncological surgeon performed a laparotomy to assess the possibility of radical resection. Subsequently, the thorax was opened by median sternotomy. Massive calcifications in the ascending aorta (porcelain aorta) were found and the cardiosurgeon considered discontinuation (Figure 1A). Ultimately, the decision to proceed with the operation was made. Aortic valve replacement (biological prosthesis Medtronic® Hancock II size 21) with implantation of an ascending aorta prosthesis in the supracoronary position (Vascutek® prosthesis size 26) with extracorporeal circulation (ECC) was performed (Figure 1B). Time of ECC was 148 min. The patient returned to normal circulation without complications. After weaning from ECC, protamine sulfate was administered to reverse the heparin action necessary during cardiopulmonary by-pass. Fresh frozen plasma and platelets were supplemented additionally, to enable the oncological surgeon to perform his part of the operation without disturbance of hemostasis. In the second stage, the oncological team performed total gastrectomy with D1 lymphangiectomy and Roux-en-Y anastomosis (Figure 1C). The procedure was supplemented with feeding jejunostomy. The spleen was removed for technical reasons. Additionally, cholecystectomy was performed because of cholelithiasis. The entire operation finished without complication in a total time of 320 min. Throughout the operation the patient received 4 units of blood, 6 units of fresh frozen plasma, and 2 units of platelet concentrate. The patient was extubated 33 h after the operation. Immediately after the surgery, the patient was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit, staying there for 6 d. She did not present any abdominal complications. Pericardial drainage was removed on postoperative day 3, and abdominal drainage on day 5. Apart from postoperative depression and slight disorientation, the postoperative course was without problems.

On postoperative day 7, the patient was transferred to the Department of Surgical Oncology for further postoperative care. Psychological care was introduced. Oral feeding was gradually introduced during this period. Postoperative pathological examination of the tumor revealed adenocarcinoma, intestinal type according to Lauren’s classification. The subserosal layer was infiltrated (pT2b), and metastases were found in 2 of 8 lymph nodes (pN1) (stage II gastric cancer).

The patient has been followed up for a total of 6 mo to date, with no complications noted.

This case is worth presenting because it highlights a number of important issues. Firstly, it is crucial to prepare the patient for surgery thoroughly. This includes taking the patient’s history and performing all necessary specialist consultations, bearing in mind various co-existing diseases. Once this has been executed, it becomes possible to plan the optimal treatment. In 2002, recommendations for the management of asymptomatic patients with severe valvular heart disease were established by a European workgroup[1]. These stated that management of asymptomatic patients with severe valvular heart disease should be based on individual assessment of the risk to benefit ratio. There is a strong need to introduce standards for the diagnosis and management of cardiological diseases in order to decrease the number of cardiac complications in the perioperative period.

Secondly, the existence of highly specialized Departments (Cardiological, Cardiosurgical, Oncological, Endocrinological, etc.) within one unit enabled efficient diagnostics, decision making, simultaneous surgical procedures and safe postoperative care in the Intensive Care Unit. This case shows that complex procedures should be performed in specialist units which should be fully staffed and resourced, to provide optimal investigation and treatment for patients with complex acquired heart disease.

Thirdly, this case proves that a thoroughly executed taking of the patient’s history and physical examination helps to prevent incidental omission of important, potentially life-threatening diseases. Cardiological consultations ordered more frequently could lead to increased detection of asymptomatic cardiac diseases and help to avoid later cardiovascular complications. The systematic increasing age of oncological patients has led to the development of a new branch of surgical oncology, called geronto-oncology. This approach may facilitate more individualized treatment, taking into account patient’s co-existing diseases.

To optimize the outcome in this case, the decision to perform simultaneous surgical treatment was made. It appeared that there were more arguments supporting the decision to perform simultaneous surgery (even though such a modus operandi is rather rare) then those backing the alternative, i.e. two consecutive surgeries[7,8]. The grounds for simultaneous surgery were: (1) extension of the sternotomy incision through mini-laparotomy is a standard procedure in cardiac surgery and in coronary artery bypass surgery (assessment of the gastroepiploic artery); (2) such a procedure does not increase the postoperative risk; and (3) performance of a mini-laparotomy allowed for evaluation of the extent of the neoplastic process in the abdomen and consequently for deciding whether the cancer was operable and whether its simultaneous resection was feasible. If an extensive spread of the disease had been noted, radical surgery could have not been performed or a two-step surgery might have been necessary after 3-4 wk.

The first step was undertaken by an oncological surgeon; laparotomy was performed to assess the possibility of radical resection of gastric cancer. Then the chest was opened and cardiac surgery performed, and after finishing the valve replacement and closure of the chest, the oncological team did their work. In our opinion this was the safest way, which allowed the performance of the second part of the operation without hemostatic problems that could occur after high dose heparin infusion necessary for the ECC. A different approach could be considered if there was a risk of serious bleeding from the resection lines or anastomoses during the heart-lung machine working time. Additionally, this sequence is important to reduce the risk of mediastinitis. Potential disadvantages of the simultaneous surgery were: (1) increased surgical risk resulting from performing the oncological step after protamine sulfate was administered; and (2) limited operation field allowing for resection of regional perigastric lymph nodes only (i.e. lymphadenectomy type D1).

In a case such as the one we have described here, performing oncological surgery without diagnosing critical aortic stenosis should be treated as malpractice since this scenario could potentially lead to the patient’s death.

| 1. | Iung B, Gohlke-Bärwolf C, Tornos P, Tribouilloy C, Hall R, Butchart E, Vahanian A. Recommendations on the management of the asymptomatic patient with valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:1253-1266. |

| 3. | Cuschieri A, Weeden S, Fielding J, Bancewicz J, Craven J, Joypaul V, Sydes M, Fayers P. Patient survival after D1 and D2 resections for gastric cancer: long-term results of the MRC randomized surgical trial. Surgical Co-operative Group. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1522-1530. |

| 4. | Głuszek S, Matykiewicz J. TNM staging and assessment of resectability of stomach cancer in diagnostic laparoscopy. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26:272. |

| 5. | Ganiats TG, Browner DK, Dittrich HC. Comparison of Quality of Well-Being scale and NYHA functional status classification in patients with atrial fibrillation. New York Heart Association. Am Heart J. 1998;135:819-824. |

| 6. | Davenport DL, Bowe EA, Henderson WG, Khuri SF, Mentzer RM Jr. National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) risk factors can be used to validate American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification (ASA PS) levels. Ann Surg. 2006;243:636-641; discussion 641-644. |

| 7. | Jones JM, Melua AA, Anikin V, Campalani G. Simultaneous transhiatal esophagectomy and coronary artery bypass grafting without cardiopulmonary bypass. Dis Esophagus. 1999;12:312-313. |

| 8. | Briffa NP, Norton R. Simultaneous oesophagectomy and CABG for cancer and ischaemic heart disease. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1993;7:557-558. |

Peer reviewer: Matthew James Schuchert, MD, FACS, Assistant Professor of Surgery, Heart, Lung and Esophageal Surgery Institute, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Shadyside Medical Building, 5200 Centre Avenue, Suite 715, Pittsburgh, PA 15232, United States

S- Editor Wang YR L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Zheng XM