CASE REPORT

A 51-year-old man was referred to our hospital for further evaluation of a probable gallbladder mass lesion and pancreatic cystic tumor. The patient initially visited another hospital because of fever and right upper quadrant abdominal pain. He had been treated for acute cholecystitis and showed clinical improvement. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed a probable gallbladder tumor and a pancreatic cystic tumor, therefore, he was referred to our hospital. At our initial evaluation, the patient was symptom free and the physical examination was normal. The patient had a history of alcohol consumption equivalent to 300 g/wk of ethanol. There was no history of pancreatitis. In laboratory analysis, white blood cell count was 5180/μL, hemoglobin 13.2 g/dL, and platelet count 218 000/μL. Aspartate aminotransferase was 31 IU/L (normal 1-39 IU/L), alanine aminotransferase was 14 IU/L (normal 1-39 IU/L), total bilirubin 0.4 mg/dL (normal 0.1-1.2 mg/dL), amylase 23 IU/L (normal 20-104 IU/L), lipase 14 IU/L (normal 6-52 IU/L), carbohydrate antigen 19-9 11.3 U/mL (normal 0-37 U/mL), carcinoembryonic antigen 1.5 ng/mL (normal 0-5.0 ng/mL), total cholesterol 194 mg/dL (normal 1-240 mg/dL), and triglycerides 129 mg/dL (normal 1-250 mg/dL). A repeat abdominal CT revealed small stones in the gallbladder and mild dilatation of peripheral intrahepatic ducts without central intrahepatic and extrahepatic duct dilatation. Also, a 1.7-cm diameter, well-marginated, round, low-density lesion on the pancreatic body, compatible with a cystic lesion (Hounsfield units; pre-enhanced, ≤ 20 HU), was seen without post-contrast enhancement of the central portion. Rim enhancement equal to the adjacent pancreas parenchyma was seen. Pancreas parenchyma was seen with slightly atrophic changes (Figure 1). Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) revealed a hyperechoic polypoid lesion of 14.1 mm on the fundal area of the gallbladder, with a posterior acoustic shadow. EUS also showed a 17 mm × 19 mm solid, round hypoechoic lesion on the pancreatic body. There were no other findings compatible with pancreatitis (Figure 2). EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) was not available at that time in our hospital. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was performed, which found irregular dilatations of the peripheral intrahepatic ducts, without involvement of the extrahepatic and common bile ducts. Bile duct sweepings by balloon retrieval catheter showed bile sludge and Clonorchis sinensis (C. sinensis) adult organisms. Endoscopic pancreatography revealed mild displacement of the main pancreatic duct of the body due to a mass effect, but no cyst filling. After performing CT, EUS and ERCP, even though there was some disagreement about the pancreatic lesion, we thought that it was a solid neoplasm. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was not performed to evaluate the pancreatic lesion further. At that time, we did not think about pseudocyst filled with semisolid lipid. The patient underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy and body and tail pancreatectomy because of our concern that it was a solid pancreatic neoplasm. On pathological examination, the gallbladder showed xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis with C. sinensis infection. The pancreatic gross specimen revealed a well-encapsulated, unilocular cystic lesion filled with yellowish muddy material, which measured 17 mm in diameter (Figure 3). Microscopic findings of the resected cystic lesion were compatible with those for a pseudocyst. On hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining, the lining of the cystic lesion consisted of fibrous and granulation tissue with no epithelial lining. Multiple extracellular fat vacuoles were shown in the cystic lesion. Findings were different from the lipocytes of a pancreatic lipoma. The surrounding pancreatic parenchyma showed mild inflammatory changes but there was no evidence of diffuse chronic pancreatitis. Sudan black B stain showed that the pseudocyst contents were lipid droplets (Figure 4A and B). No neoplasm was seen.

Figure 1 Image of the cystic lesion by contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (arrow).

There was a 17-mm well-marginated, round, low-density lesion in the body of the pancreas. The central contents of the lesion showed no enhancement in the post-contrast-enhanced image.

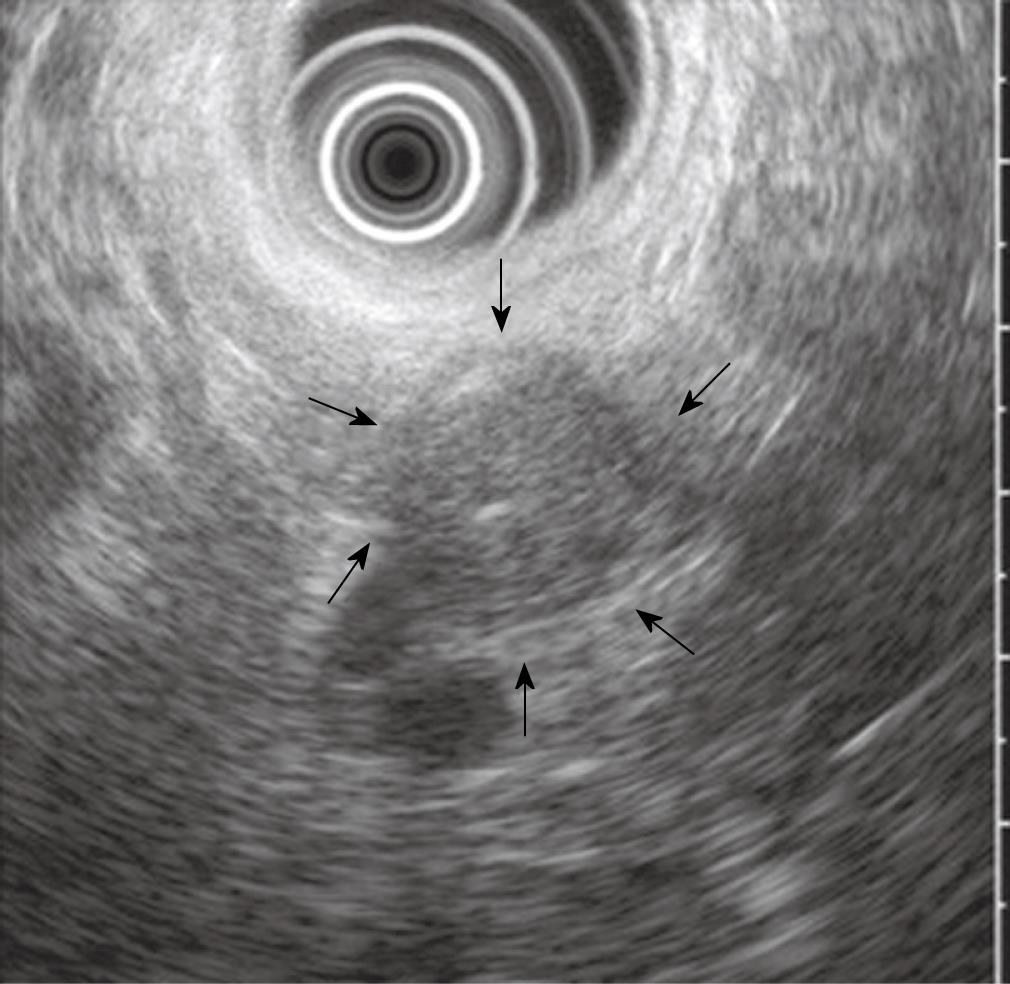

Figure 2 Image of the cystic lesion on EUS.

It showed a 17-mm × 19-mm, well-circumscribed, round, homogenous, hypoechoic solid lesion with central echogenicity (arrows).

Figure 3 Gross finding of the pancreatic cystic lesion.

There was a 17-mm, unilocular, well-encapsulated cystic lesion filled with yellowish muddy material in the body of the pancreas.

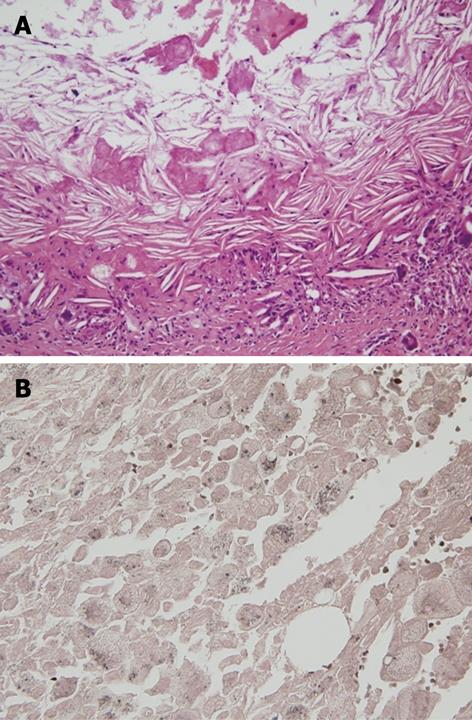

Figure 4 Microscopic finding of the pancreatic pseudocyst.

A: Microscopic finding of the pancreatic pseudocyst. HE staining showed multiple lipid droplets and cholesterol clefts; B: Sudan black B stain showed positive findings for lipid droplets, stained with a dark brown color.

DISCUSSION

Cystic lesions of the pancreas are being detected more often as sensitive abdominal imaging tests are being used for multiple indications. Some of these lesions are either premalignant or malignant. Therefore, it is important to differentiate between benign (serous), malignant/premalignant, and inflammatory (pseudocysts) cystic lesions[1]. The decision with respect to observation or operation is further complicated by the fact that a significant percentage of the patients with cystic lesions have pseudocysts rather than cystic neoplasms. Pancreatic pseudocysts are non-neoplastic and have been reported to account for 70%-90% of pancreatic cystic diseases. The neoplastic pancreatic cystic diseases represent 10%-15% of all pancreatic cystic diseases[3]. However, more recent studies have reported that 40%-50% of patients with cysts have a history of pancreatitis. This suggests that pseudocysts only account for 40%-50% of pancreatic cystic lesions, and not 70%-90%[4,5]. They have explained that these dramatic differences were probably due to increased detection of small asymptomatic cysts in some studies, as well as differences in referral patterns[4]. Pseudocysts are cystic cavities that typically have or had connections with the pancreas, have no epithelial lining, and develop after acute or chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic trauma and surgery[6]. The diagnosis of a pancreatic pseudocyst depends on the clinical history and associated findings within the pancreas, such as gland atrophy, duct dilatation, calcification of the parenchyma, and calculi in the pancreatic duct. Although a prior history of pancreatitis cannot by itself justify the diagnosis of pancreatic pseudocysts, cystic lesions that occur without a history of pancreatitis suggest a diagnosis of cystic neoplasms[2]. Differentiation between pseudocysts and cystic neoplasms can be aided by CT, MRI, and EUS. The CT findings of a pseudocyst include a round or oval fluid collection with variably a thin or thick wall that shows evidence of contrast enhancement. Contrast-enhanced CT typically shows rim enhancement of pseudocysts[2], which was present in our case. Most pseudocysts are unilocular and septations are infrequent[1]. The usefulness and accuracy of EUS in the differential diagnosis of pancreatic cystic diseases continues to evolve[7-14]. Koito et al[7] have reported the classification of the internal structures of solitary cystic lesions of the pancreas, and have compared them with pathological findings. They have concluded that the EUS findings were relatively accurate. However, Ahmad et al[8,9] have reported that endoscopic features alone (without FNA) cannot reliably differentiate between benign and malignant or neoplastic and non-neoplastic cystic lesions of the pancreas. Song et al[10] have reported that pseudocysts exhibit echogenic debris and parenchymal changes more often than do cystic tumors. In contrast, septae and mural nodules are found more frequently in cystic tumors than in pseudocysts. In our case, EUS showed a well-circumscribed, hypoechoic, round lesion with central echogenicity. These findings are more compatible with a pancreatic solid mass than a cystic lesion. The lesion was not hyperechoic as in lipoma. We did not perform FNA. If we had done so, it would probably have shown lipids and debris that were suggestive of a pseudocyst. With endoscopic pancreatography, 70% of pseudocysts have communication with the pancreatic ductal system, while serous cystadenoma, mucinous cystadenoma, and mucinous cystadenocarcinoma usually do not. Our patient presented with no evidence of pancreatitis on medical history, laboratory findings or imaging evaluations. He had documented biliary calculus disease and a history of alcohol consumption equivalent to 300 g/wk of ethanol. As a result of suspicion of a solid pancreatic neoplasm, the pancreatic body and tail and spleen were resected. The pathology revealed a well-encapsulated, unilocular, pancreatic cystic mass that measured 17 mm in diameter, which was filled with yellowish muddy material. Sudan black B stain revealed that the mass was a pseudocyst with lipid contents (lipid droplets and cholesterol clefts). This is different from a pancreatic lipoma, which would have been composed of lobules of mature adipose cells that were sharply delineated from the surrounding pancreatic tissue by a thin fibrous capsule[13]. Lipomas are benign tumors of homogeneous adipose tissue that are histopathologically identical to subcutaneous fat. CT findings of pancreatic lipoma include homogeneous distribution of dense adipose tissue, with no central or peripheral contrast enhancement[14].

In our case, gallbladder stones and infection with C. sinensis could have been the causes of pancreatitis. However, our patient did not have clinical manifestations and a history of pancreatitis. The pathophysiological process that leads to development of this lesion is uncertain. As we known, pancreatic pseudocysts are formed by the walling off of areas of peripancreatic hemorrhagic fat necrosis with fibrous tissue. As such, they usually are composed of central necrotic-hemorrhagic material rich in pancreatic enzymes, surrounded by non-epithelial-lined fibrous walls of granulation tissue. Fat necrosis is the first step in many pseudocysts. Therefore, small amounts of necrotic fat are common in pseudocysts. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of pancreatic pseudocyst densely filled with lipids. Our patient was not obese (body mass index 19.1), and the CT scan showed small/normal amounts of peripancreatic and retroperitoneal fat. Necrosis of peripancreatic fat can progress to liquefaction, with subsequent organization and encapsulation. Our patient’s lesion appeared to be more than 50% intrapancreatic. Another origin of fat material in the pancreas is focal fatty replacement of the pancreas. Pancreatic lipomatosis or fatty replacement of the pancreas is the most frequent pathological finding in the adult pancreas. It is associated with a variety of diseases, including obesity, diabetes mellitus, chronic pancreatitis, hereditary pancreatitis, obstruction of the pancreatic duct by calculus or tumor, and cystic fibrosis. It is typically distributed as multiple tiny nodules throughout the pancreas; however, some investigators have found uneven fatty replacement of the pancreas, which is seen as a focal fatty mass[15,16]. This appearance may simulate a pancreatic mass such as a cystic neoplasm or other pancreatic tumor. Our patient did not have a fatty pancreas by CT, nor in the resected specimen. It is possible that our patient had focal fatty pancreas, unrecognized pancreatitis in the past, and residual organizing fatty necrosis. Unenhanced CT has a diagnostic role in comparing adjacent retroperitoneal fat with a negative attenuation value and parenchymal fat. Moreover contrast-enhanced CT may not show a negative attenuation value of this focal fatty replacement because of normal adjacent pancreatic parenchymal contrast enhancement[17,18]. MRI may be helpful for confirming the presence of this type of focal fatty replacement of the pancreas. Chemical shift MRI has the advantage that the reduction in signal intensity of focal fatty replacement on opposed-phase images differentiates focal fatty replacement of the pancreas from true pancreatic tumors, which in general do not contain lipid[17-19]. Our patient’s cystic lesion would likely have shown high fat content by MRI, if it had been performed. Another possibility of the origin of fat material in the pseudocyst is that this lesion is a thrombosed splenic artery aneurysm. The position in the pancreas is compatible with this possibility. The cholesterol-appearing spicules in the wall also are consistent with a vascular problem. When fat is stored in organs (e.g. liver or pancreas), the vast majority is in triglyceride, and not cholesterol. However, our patients did not have a splenic artery aneurysm or any vascular disorder by CT, nor in the resected specimen.

CT showed that our patient’s lesion was cystic. EUS is thought to be more accurate, therefore, the presumed solid lesion was resected. We did not attempt to make a preoperative tissue diagnosis because we assumed that all solid masses needed resection. Even though the risk appears to be quite low, percutaneous FNA biopsy of the pancreas may disseminate tumor cells intraperitoneally or along the needle path in patients who are believed to be candidates for potentially curative resection. If we had performed MRI with fat content analysis, or EUS-guided FNA, we probably would have been able to identify the lipid content of the lesion. Resection more definitely evaluated for malignancy.

In summary, we reported a unique case of a pancreatic pseudocyst filled with semisolid lipids, which appeared by EUS as a sold mass, and was therefore resected. Additional preoperative testing may have identified the true nature of the lesion. A high lipid content of pseudocysts is rare.