Published online Dec 21, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i47.5936

Revised: July 7, 2010

Accepted: July 14, 2010

Published online: December 21, 2010

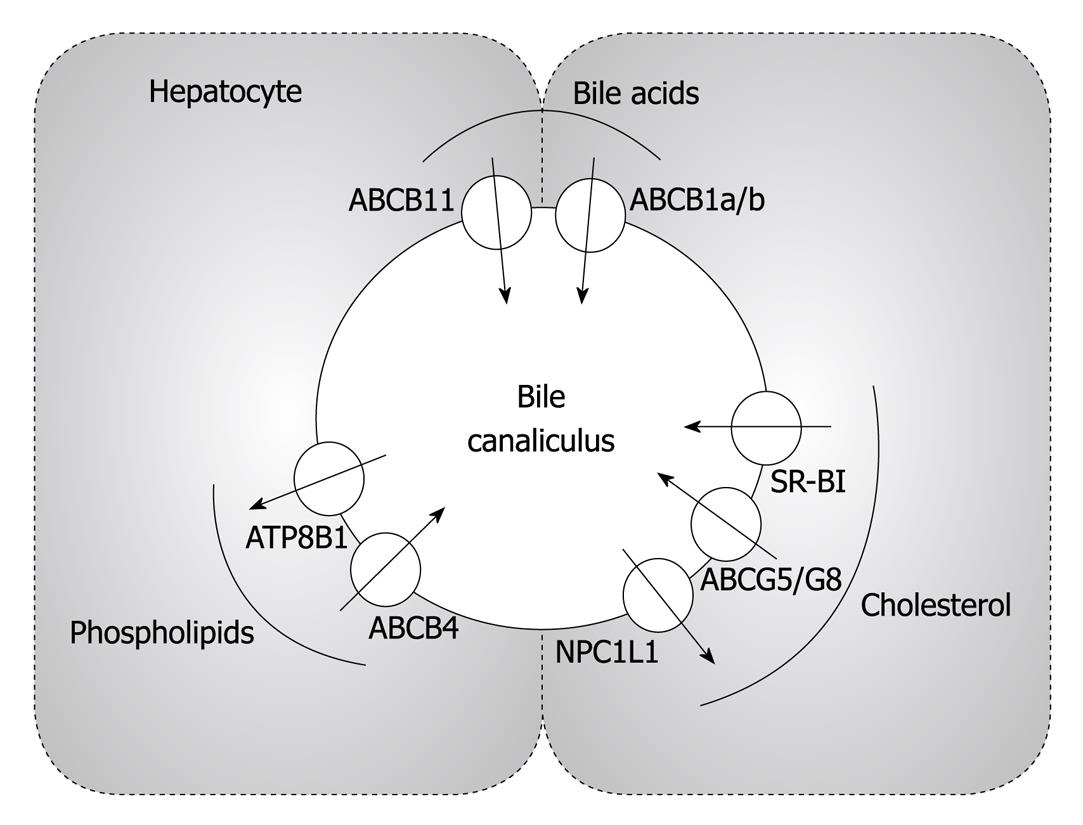

Biliary cholesterol secretion is a process important for 2 major disease complexes, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and cholesterol gallstone disease. With respect to cardiovascular disease, biliary cholesterol secretion is regarded as the final step for the elimination of cholesterol originating from cholesterol-laden macrophage foam cells in the vessel wall in a pathway named reverse cholesterol transport. On the other hand, cholesterol hypersecretion into the bile is considered the main pathophysiological determinant of cholesterol gallstone formation. This review summarizes current knowledge on the origins of cholesterol secreted into the bile as well as the relevant processes and transporters involved. Next to the established ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters mediating the biliary secretion of bile acids (ABCB11), phospholipids (ABCB4) and cholesterol (ABCG5/G8), special attention is given to emerging proteins that modulate or mediate biliary cholesterol secretion. In this regard, the potential impact of the phosphatidylserine flippase ATPase class I type 8B member 1, the Niemann Pick C1-like protein 1 that mediates cholesterol absorption and the high density lipoprotein cholesterol uptake receptor, scavenger receptor class B type I, is discussed.

- Citation: Dikkers A, Tietge UJ. Biliary cholesterol secretion: More than a simple ABC. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(47): 5936-5945

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i47/5936.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i47.5936

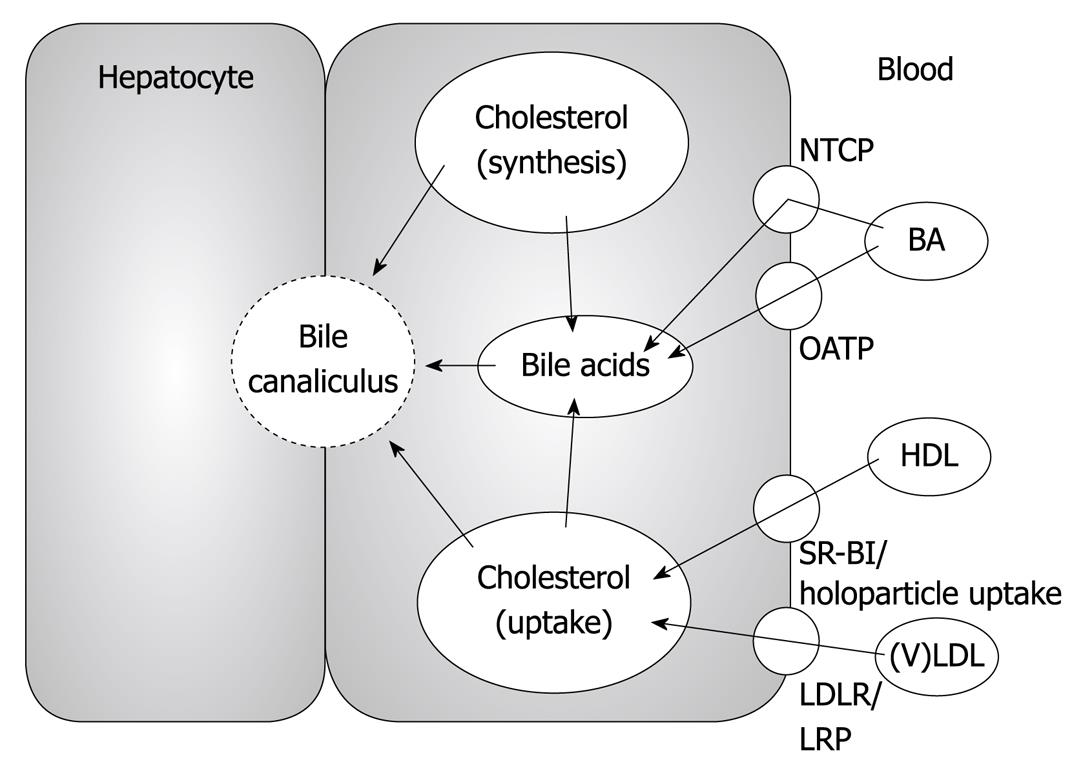

The liver plays a central role in cholesterol metabolism (Figure 1). Hepatocytes not only express a number of different lipoprotein receptors including low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR), LDLR-related protein (LRP) and scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI), that enable them to take up cholesterol from virtually all lipoprotein subclasses, but cholesterol is also synthesized de novo within the liver in a regulated fashion[1]. In addition to these input pathways into the hepatic cholesterol pool, the liver is equipped to actively secrete cholesterol via 2 different routes: (1) within triglyceride-rich very low density lipoproteins (VLDL)[2,3], thereby supplying peripheral cells with fatty acids, fat soluble vitamins and cholesterol; (2) by secretion into the bile either directly as free cholesterol or after conversion into bile acids, thereby providing a means of irreversible elimination of cholesterol from the body via the feces[4,5]. In general, the different hepatic cholesterol fluxes are interrelated, however, some are also markedly separated, as will be discussed later in this review.

Biliary cholesterol secretion itself is directly linked to 2 major disease complexes with a high relevance for health care systems worldwide, namely atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (CVD) and gallstone disease. In atherosclerotic CVD, biliary cholesterol secretion is considered the final step in the completion of the reverse cholesterol transport (RCT) pathway[6,7]. The term RCT comprises the transport of peripheral cholesterol back to the liver for excretion into bile, most importantly cholesterol accumulating within macrophage foam cells in atherosclerotic lesions[8]. For RCT an enhanced biliary secretion of cholesterol originating from peripheral pools relevant for CVD is desirable. On the other hand, increased biliary cholesterol secretion is related to biliary cholesterol supersaturation, which is an important determinant for the formation of cholesterol gallstones that constitute more than 90% of all gallstones[9,10]. Notably, both CVD[11,12] and gallstone disease[13] also have a strong inflammatory component that plays an important role in the pathogenesis of these diseases. However, an in-depth understanding of the metabolic processes and transporters involved in the regulation of biliary cholesterol secretion is important and might conceivably reveal relevant targets for the treatment of CVD as well as cholesterol gallstone disease.

The most relevant source of cholesterol secreted into the bile is cholesterol derived from plasma lipoproteins, and a less relevant source is cholesterol originating from de novo synthesis or hydrolysis of stored cholesteryl ester[14]. High density lipoprotein (HDL) appears to be the preferential contributor for cholesterol secreted into bile[15]. In humans with a bile fistula, cholesterol originating from HDL appeared more rapidly in bile compared with LDL cholesterol[16]. Additional evidence for a more prominent role of HDL over LDL came from experiments demonstrating that biliary cholesterol secretion remained essentially unchanged when plasma LDL cholesterol levels specifically were reduced by 26% by means of LDL apheresis[17]. In contrast, reduction in plasma LDL cholesterol resulted in a consecutive decrease in biliary bile acid secretion[17], thereby lending further experimental evidence to older literature suggesting a metabolic compartmentalization of hepatic cholesterol pools with regard to bile acid synthesis vs direct biliary secretion[18,19]. However, definitive studies exploring the underlying metabolic pathways are still lacking.

It is, however, important to note, that modulation of plasma HDL cholesterol levels does not influence mass biliary cholesterol secretion, since ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) knockout mice[20] as well as apolipoprotein-A-I (apoA-I) knockout mice[21,22] display unaltered biliary cholesterol secretion rates. These data indicate that specific intrahepatic metabolic and transport processes are most relevant and rate-limiting for biliary secretion of cholesterol.

The hepatocyte is a polarized cell with a basolateral (sinusoidal) and an apical (canalicular) plasma membrane. Uptake of cholesterol from the plasma compartment occurs on the basolateral site (Figure 1), while biliary cholesterol secretion is an apical process (Figure 2). Hepatic cholesterol synthesis is carried out intracellularly. This polarization implies that a means of transport must exist for exogenous as well as endogenously synthesized cholesterol to reach the site where the biliary secretion process takes place.

Of note, cholesterol is also used for the synthesis of bile acids, and a number of factors modulating bile acid synthesis impact on hepatic cholesterol homeostasis. However, the regulation of bile acid synthesis will not be discussed, we refer to recent comprehensive reviews covering this topic[23,24].

The detailed mechanisms of intracellular cholesterol trafficking in hepatocytes are not understood thus far, especially how these relate to biliary cholesterol secretion. However, a few known transport proteins have been studied in more detail to test the effect of gain- or loss-of-function manipulations on biliary cholesterol secretion. A prominent example of such a protein is the Niemann-Pick type C protein 1 (NPC1) that plays a role in the intracellular trafficking of lipoprotein-derived cholesterol[25,26]. Specifically, NPC1 is involved in moving free cholesterol from the late endosomal/lysosomal compartment to the cytosol[25,26]. On a chow diet, mice lacking NPC1 expression had 37% higher biliary cholesterol secretion rates compared with controls[27]. However, when fed a 2% cholesterol-containing diet, biliary cholesterol secretion was significantly decreased in NPC1 knockout mice, while it increased 3.7-fold in wild-type controls[27]. These results indicated that NPC1 may become critical under conditions of high cholesterol intake. In turn, hepatic overexpression of NPC1 increased biliary cholesterol secretion by approximately 2-fold in chow-fed wild-type and high cholesterol diet-fed NPC1 knockout mice. However, no effect was observed in wild-type mice fed a 2% cholesterol diet[27]. The interpretation of this latter result is not straightforward, but other cholesterol metabolism pathways are also affected by NPC1, and changes in hepatic cholesterol content may play an additional role in explaining the observed phenotypes. Although more work is required to provide a detailed understanding of the role of NPC1, the presently available studies indicate that NPC1 is important in regulating the availability of cholesterol at the canalicular membrane for the biliary secretion process. Also NPC2, which plays a very similar role in intracellular cholesterol trafficking[28], is expressed in liver, is detectable in bile, and may be involved in the transport of cholesterol destined for biliary secretion. However, thus far no mechanistic studies have been performed, but a significant increase in hepatic NPC2 expression in gallstone-susceptible vs gallstone-resistant mouse strains has been reported[29]. Also the expression of another carrier protein, the sterol carrier protein-2 (SCP2), impacts biliary cholesterol secretion, with SCP2 overexpression increasing biliary secretion of cholesterol[30,31] and decreased SCP2 expression having the opposite effect[32]. Members of the steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein family of cholesterol transport molecules may also represent candidates to influence biliary cholesterol secretion[33,34]. However, thus far it has only been shown that StARD1 overexpression increases bile acid synthesis[35], while the absence of StARD3 in knockout mice had no impact on biliary sterol secretion[36]. In addition to intracellular cholesterol transport proteins, enzymes modulating the amount of free cholesterol present within a hepatocyte could also be expected to impact biliary cholesterol secretion. While this was shown to be the case for the neutral cholesteryl ester hydrolase[37], decreasing ACAT2 expression had no effect on biliary cholesterol output[38].

On the apical membrane several transporters are directly involved in the biliary cholesterol secretion process. Transporter expression and activity is regulated by transcriptional as well as posttranscriptional mechanisms. Important transcriptional regulators are the nuclear hormone receptors liver X receptor (LXR; 2 isoforms LXRα, NR1H3, and LXRβ, NR1H2) and farnesoid X receptor (FXR, NR1H4), among others. For the specifics of LXR- and FXR-mediated gene regulation we refer to recent articles dealing with these topics[23,39-41]. In general, LXR is a nuclear receptor activated by oxysterols and functions as a sterol sensor exerting control on cholesterol metabolism[39,40]. As a general scheme, LXR activation stimulates metabolic processes favoring cholesterol elimination from the body, e.g. by increasing biliary cholesterol secretion via increased expression of ABCG5/G8[42] (see below) or by increasing the conversion of cholesterol to bile acids via increased expression of the cholesterol 7α-hydroxylase gene, at least in rodents[43].

On the other hand, FXR is the nuclear receptor activated by bile acids and orchestrates an adaptive response of the hepatocyte to altered bile acid levels[23,41]. In cholestatic conditions, FXR induces a downregulation of bile acid synthesis[23], a reduction in bile acid uptake into hepatocytes by decreasing the expression of the cellular uptake receptors[23] and an increased biliary secretion of bile acids by increasing the expression of specific transporters such as ABCB11[44] (see below).

In general, biliary bile acid secretion is the main driving force for the secretion of phospholipids and cholesterol[45]. Infusion of bile acids results in a dose-dependent increase in biliary cholesterol secretion[46]. However, cholesterol secretion into the bile also critically depends on functional biliary phospholipid secretion which is required for the formation of mixed micelles[46]. This is evidenced by the Abcb4 knockout mouse, that in the absence of this key biliary phospholipid transporter almost completely lacks biliary cholesterol secretion[47,48]. The following transporters are specifically involved in these processes:

ABCB4 has historically been named multi-drug resistance P-glycoprotein 2 (MDR2). ABCB4 functions as a phosphatidylcholine (PC) flippase translocating PC from the inner to the outer leaflet of the canalicular membrane[45]. Biliary cholesterol secretion is fully dependent on the functionality of ABCB4 and thereby biliary phospholipid secretion. In Abcb4-deficient animals, biliary cholesterol secretion is virtually absent[47,48]. Furthermore, PC decreases the toxic effects of bile acids on the canalicular membrane, and Abcb4 knockout mice as well as patients lacking this transporter develop a progressive liver disease[49,50].

ATPase class I type 8B member 1 (ATP8B1) is a P-type ATPase that flips phosphatidylserine (PS) from the outer to the inner leaflet of the canalicular membrane resulting in a reduction in the PS content and a consecutive increase in the sphingomyelin content of the outer canalicular leaflet[51,52]. In humans, mutations in ATP8B1 cause severe chronic or periodic cholestatic liver disease[53,54]. A mutation resulting in severe liver disease is the glycine to valine substitution at amino acid 308 (G308V)[54]. In mice carrying the Atp8b1G308V/G308V mutation Atp8b1 is almost completely absent, which causes enhanced biliary excretion of PS and also cholesterol, mainly due to decreased rigidity of the outer canalicular leaflet (see below)[52,55].

ABCB11 is classically referred to as the bile salt export pump (BSEP; also known as sister of P-glycoprotein) and is mediating biliary secretion of bile acids[44,56]. A 2-fold increase in ABCB11 expression in transgenic mice resulted in increased biliary output of bile acids[57]. Notably, expression of other biliary transporters remained unaltered providing additional evidence that biliary bile acid secretion is the driving force for the secretion of the other lipid species into bile[57]. However, in Abcb11 knockout mice, there is still substantial residual biliary bile acid secretion and the expression of Mdr1a (Abcb1a) and Mdr1b (Abcb1b) was found to be upregulated indicating a potential compensation mechanism[58]. Subsequently, triple knockout mice lacking all 3 transporters have been generated to prove this concept, and indeed these mice develop an extreme cholestatic phenotype[59].

How do these transporters work together in the process of bile formation? First, the specific properties of the canalicular membrane need to be considered, since this has to fulfill 2 key functions: (1) withstand extremely high concentrations of bile acids, that are powerful detergents able to basically solubilize normal plasma membranes resulting in cell death; and (2) still allow for regulated secretion of the different bile components. The answer to these questions seems to lie in the asymmetry of the canalicular membrane with a high content of sphingomyelin and cholesterol in the outer leaflet[60]. In membranes composed of glycerophospholipids (PC, PS and phosphatidylethanolamine) lipids are loosely packed, the so-called “liquid disordered” phase[61,62]. Addition of sphingomyelin and cholesterol induces a more rigid membrane structure, the so-called “liquid ordered” phase that does not allow for the intercalation of detergents and thereby the membrane is rendered increasingly resistant against detergents[61,63,64]. The task of ATP8B1 in this model would be to preserve the rigid structure of the outer canalicular leaflet by inward flipping of PS. The amphipathic bile acids are actively excreted into the canalicular lumen by ABCB11, where they form simple micelles in the aqueous environment of the bile[9,46]. Phospholipids are translocated to the outer leaflet of the canalicular membrane by ABCB4 where they are added to the simple micelles resulting in mixed micelles[9,46]. However, the precise mechanism of how this occurs is still elusive. Subsequently, cholesterol is then taken up into these mixed micelles[9,46]. The authentic cholesterol transporters that play a role in this process are discussed below.

The transport system contributing quantitatively the major amount of cholesterol secretion into the bile is the obligate heterodimer transporter pair ABCG5/ABCG8[65-67]. These are expressed almost exclusively in the liver and the intestine, and respective mutations have been identified as the disease substrate for sitosterolemia, a rare autosomal recessive disorder which is characterized by the accumulation of plant sterols in blood and tissues[68,69]. This accumulation is caused by increased sterol absorption from the diet and decreased biliary sterol secretion[70,71]. In the intestine, ABCG5/G8 secrete absorbed plant sterols back into the intestinal lumen, while on the bile canaliculus ABCG5/G8 mediate biliary plant sterol as well as cholesterol secretion into bile[70,71]. Since in healthy individuals, plasma plant sterol levels are very low, ABCG5/G8 represent, under physiological conditions, mainly a transport system for cholesterol. This is mirrored by the fact that biliary cholesterol secretion in ABCG5 and/or ABCG8 knockout mice is reduced by 75%[71-73]. In turn, transgenic overexpression of ABCG5/G8 resulted in an increase in biliary cholesterol secretion that was directly proportional to the copy numbers of the transgene over a wide range, indicating that under these conditions neither delivery of cholesterol to the transporters nor the level of cholesterol acceptors within the bile are rate-limiting[74]. In addition, ABCG5 and ABCG8 are targets of the nuclear hormone receptor LXRα and the increase in biliary cholesterol secretion observed upon LXR activation with endogenous or synthetic ligands depends largely on functional ABCG5/G8 expression[75]. Interestingly, also the increasing effects of cholate as well as diosgenin on biliary cholesterol secretion depend on the functional expression of ABCG5/G8 and subsequently are not seen in mice lacking either or both of the transporters[74,76]. Notably, there are as yet ill-defined ABCG5/G8-independent pathways of biliary cholesterol secretion[77] (see also below).

With relevance to atherosclerotic CVD, when human ABCG5/G8 transgenic mice overexpressing the transgene in the liver as well as in the intestine were crossed into the atherosclerotic LDLR-/- genetic background, these mice developed significantly less atherosclerosis compared with wild-type controls[78]. On the other hand, only hepatic overexpression of ABCG5/G8 does not alter atherosclerosis in LDLR-/- as well as apoE-/- mice[79], unless intestinal cholesterol absorption is also reduced by ezetimibe[80]. With relevance to gallstone disease, recently specific mutations in ABCG5/G8, namely ABCG5 R50C and ABCG8 D19H, have been identified in humans and shown to increase the risk for cholesterol gallstone disease[81-83]. Since the role of ABCG5/G8 is to increase biliary cholesterol secretion, and cholesterol gallstone formation requires increased amounts of cholesterol within bile, these respective mutations are likely to constitute a gain-of-function phenotype. However, since these association data were obtained in human studies, this concept still requires verification in an experimental setting that allows determination of cause-effect relationships.

Although several studies have shown that the ABCG5/G8 heterodimer is a key component of biliary cholesterol secretion[70,71], the molecular mechanism by which this transporter pair mediates biliary cholesterol secretion at the canalicular membrane has not been yet elucidated. This lack of insight is mainly due to the unavailability of easy to study model systems such as polarized hepatocyte cell lines, or simple and reliable methods to isolate and characterize pure apical and basolateral membranes. However, the currently most accepted model suggests that ABCG5/ABCG8 act as a liftase elevating cholesterol just sufficiently outside of the outer leaflet of the canalicular membrane to be extracted by mixed micelles[84].

The Niemann-Pick C1-like protein 1 (NPC1L1) was originally identified as a key regulator of intestinal cholesterol absorption and the molecular target of the cholesterol absorption inhibitor ezetimibe[85,86]. It is also highly expressed in human liver, but not in rodents[87]. In human hepatocytes, NPC1L1 is localized to the canalicular membrane[88]. Similar to its role in the intestine, hepatic NPC1L1 apparently facilitates the uptake of newly secreted biliary cholesterol[89]. In NPC1L1 transgenic mice with hepatic overexpression of the transgene, a more than 90% decrease in biliary cholesterol concentration is observed without any effect on biliary phospholipid and bile acid levels. Interestingly, treatment with ezetimibe normalizes biliary cholesterol concentrations in hNPC1L1 transgenic animals[89]. Therefore, particularly in humans, ezetimibe supposedly reduces plasma cholesterol levels by inhibiting both intestinal as well as hepatic NPC1L1 activity. However, the regulation of this important cholesterol transporter and modifier of hepatic cholesterol secretion is still incompletely understood.

SR-BI has been characterized as a receptor for HDL cholesterol, mediating bi-directional cholesterol flux, either efflux or selective uptake, depending on concentration gradients[90,91]. In contrast to ABC transporters, SR-BI apparently requires no energy consumption[91]. SR-BI is mainly expressed in the liver and in steroidogenic tissue[90,91]. In hepatocytes, SR-BI mediates the internalization of HDL cholesterol without the concomitant catabolism of HDL apolipoproteins[90,91]. SR-BI is detectable in hepatocytes in vivo at both the basolateral as well as the apical membrane[92,93]. Since HDL-derived cholesterol is a major source of sterols designated for biliary secretion[15], these properties of SR-BI suggest a potential involvement in biliary cholesterol secretion.

Cholesterol uptake from HDL via SR-BI can be increased in 2 different ways, by modulating the properties of the ligand, namely HDL, as well as by changing the expression level of SR-BI. HDL modification by phospholipases decreases its phospholipid content, destabilizes the particle and makes the HDL cholesterol ester more susceptible towards SR-BI-mediated selective uptake[94-97]. Overexpression of 2 phospholipases relevant for human physiology in mice, namely group IIA secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2)[98,99] and endothelial lipase (EL)[95,97,100] has 2 major metabolic effects: (1) in plasma, HDL cholesterol levels decrease significantly, and (2) hepatic cholesterol levels increase[94,101]. While SR-BI expression or membrane localization[94,101] was not affected, consecutive in vitro studies showed that SR-BI-mediated selective uptake from sPLA2- or EL-modified HDL was increased by 77%[94] and 129%[97], respectively, explaining the increased hepatic cholesterol uptake rates. However, despite this increased SR-BI-mediated hepatic cholesterol uptake, biliary cholesterol secretion in sPLA2 transgenic mice or mice with adenovirus-mediated EL overexpression was essentially unchanged compared with controls[94,101]. As a third example, the absence of hepatic lipase also did not affect biliary cholesterol secretion, although in this study actual SR-BI-mediated uptake of HDL cholesterol was not quantified[102]. Overall, these data demonstrate that biliary cholesterol secretion remains unaltered when only the ligand, HDL, but not SR-BI expression itself is modulated.

In contrast, changes in the hepatic expression level of SR-BI directly translate into altered biliary cholesterol secretion rates. SR-BI knockout mice have biliary cholesterol secretion rates reduced by 55%[103]. Consistent with these data, adenovirus-mediated SR-BI overexpression in the liver of wild-type mice increases gallbladder cholesterol content[92] as well as biliary cholesterol secretion rates[93]. Interestingly, with relevance to disease, hepatic SR-BI overexpression increases reverse cholesterol transport[104] and is protective against atherosclerotic CVD, even though plasma HDL cholesterol levels are decreased[105,106]. In gallstone-susceptible mice, hepatic SR-BI expression was higher and associated with biliary cholesterol hypersecretion[107]. In addition, hepatic mRNA as well as protein expression of SR-BI was higher in Chinese patients with cholesterol gallstone disease compared with controls and even correlated with an increased cholesterol saturation index[108] suggesting that the link between SR-BI and biliary cholesterol secretion might be relevant for human pathophysiology as well. In this study, increased expression of LXRα was also noted in the livers of gallstone patients[108], and previous experimental work suggested that modulation of SR-BI expression results in altered expression of LXR target genes[109].

However, increased biliary cholesterol secretion in response to SR-BI overexpression was completely independent of LXR as evidenced by the use of knockout mice[93]. Surprisingly, this biological effect was also independent of functional expression of ABCG5/G8, since in ABCG5 knockout mice hepatic overexpression of SR-BI increased biliary cholesterol secretion rates to the levels of wild-type control mice and thereby normalized the cholesterol secretion deficit caused by absent ABCG5 expression[93]. To a certain extent canalicular SR-BI also acts independent of ABCB4, since hepatic overexpression of SR-BI in ABCB4 knockout mice resulted in significantly higher biliary cholesterol secretion, although in terms of mass secretion this effect was minor, indicating that cholesterol secreted via SR-BI still requires mixed micelles as acceptors[93]. Interestingly, SR-BI overexpression particularly augmented canalicular expression of the receptor[93]. Since, in SR-BI overexpression conditions, increased canalicular SR-BI localization was associated with an increased cholesterol content of the canalicular membrane and higher biliary cholesterol secretion rates[93], conceivably this biological effect was mediated by SR-BI. SR-BI requires a cholesterol gradient for transport[91], which is, however, constantly provided within the canaliculus by the direction of bile flow and the associated transport of cholesterol away from the hepatocyte. It would be interesting and physiologically relevant to explore whether SR-BI also contributes a significant part to the ABCG5/G8-independent biliary cholesterol secretion under steady-state conditions and not only has an effect in response to overexpression.

It is presently unclear how cholesterol secreted by SR-BI into the bile reaches the canalicular membrane. One possibility could be that SR-BI itself mediates this transport, since a transcytotic route of trafficking from the basolateral to the apical membrane has been proposed for SR-BI in a process that is dependent on microtubuli function[110]. However, even under conditions when microtubuli function and thereby transcytotic transport were efficiently abolished in vivo, SR-BI overexpression still significantly increased biliary cholesterol secretion[93]. These data indicate that microtubuli function is not required for the increasing effect of SR-BI on biliary cholesterol secretion. Other, as yet not characterized pathways, are therefore likely to contribute.

In our view, there are a number of interesting and relevant questions that are unresolved and should be addressed by future research in the field. The contribution of SR-BI to the ABCG5/G8-independent biliary cholesterol secretion under steady-state conditions would be important to know. Related to this, but also extending beyond SR-BI, more work appears to be required to identify and delineate the intracellular pathways for cholesterol transport that contribute to biliary cholesterol secretion. In addition to the selective uptake pathway for HDL cholesterol that is mediated by SR-BI, a holoparticle uptake pathway has also been characterized that is responsible for approximately a quarter of the total HDL cholesterol taken up into the liver[97,111-114]. However, whether this pathway contributes cholesterol for biliary secretion is currently unknown. Expanding this question, there also appears to be scope for assessing the differential contribution of apoB-containing lipoproteins vs HDL in bile acid synthesis and the respective biliary secretion of cholesterol and bile acids. Further research on these pathways would not only be relevant to increase our mechanistic insights into pathophysiology but also to define and characterize potential novel therapeutic targets for the treatment of atherosclerotic CVD and cholesterol gallstone disease.

Biliary cholesterol secretion is important for 2 major disease complexes, atherosclerotic CVD and cholesterol gallstone disease. Research thus far has provided valuable understanding of the regulation of biliary cholesterol secretion. With the identification of the ABC transporters mediating the biliary secretion of bile acids (ABCB11), phospholipids (ABCB4) and cholesterol (ABCG5/G8) the major transport proteins for the respective physiological processes have been delineated. However, more recently a number of proteins that modulate or mediate biliary cholesterol secretion such as the phosphatidylserine flippase ATP8B1, NPC1L1 and SR-BI have gained attention. Although several proteins are currently known that impact biliary cholesterol secretion, further research into the mechanisms determining their respective activities as well as the routes of intrahepatic cholesterol trafficking and the regulation of hepatic cholesterol pools is required.

| 1. | Cohen DE. Lipoprotein metabolism and cholesterol balance. 5th ed. Chichester, West Sussex, UK; Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons 2009; . |

| 2. | Ginsberg HN, Fisher EA. The ever-expanding role of degradation in the regulation of apolipoprotein B metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2009;50 Suppl:S162-S166. |

| 3. | Adiels M, Olofsson SO, Taskinen MR, Borén J. Overproduction of very low-density lipoproteins is the hallmark of the dyslipidemia in the metabolic syndrome. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1225-1236. |

| 4. | Lewis GF. Determinants of plasma HDL concentrations and reverse cholesterol transport. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2006;21:345-352. |

| 5. | Angelin B, Parini P, Eriksson M. Reverse cholesterol transport in man: promotion of fecal steroid excretion by infusion of reconstituted HDL. Atheroscler Suppl. 2002;3:23-30. |

| 6. | Wang X, Rader DJ. Molecular regulation of macrophage reverse cholesterol transport. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2007;22:368-372. |

| 7. | Linsel-Nitschke P, Tall AR. HDL as a target in the treatment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:193-205. |

| 8. | Lewis GF, Rader DJ. New insights into the regulation of HDL metabolism and reverse cholesterol transport. Circ Res. 2005;96:1221-1232. |

| 9. | Wang DQ, Cohen DE, Carey MC. Biliary lipids and cholesterol gallstone disease. J Lipid Res. 2009;50 Suppl:S406-S411. |

| 10. | Portincasa P, Moschetta A, Palasciano G. Cholesterol gallstone disease. Lancet. 2006;368:230-239. |

| 11. | Steinberg D. Atherogenesis in perspective: hypercholesterolemia and inflammation as partners in crime. Nat Med. 2002;8:1211-1217. |

| 12. | Rader DJ, Daugherty A. Translating molecular discoveries into new therapies for atherosclerosis. Nature. 2008;451:904-913. |

| 13. | Maurer KJ, Carey MC, Fox JG. Roles of infection, inflammation, and the immune system in cholesterol gallstone formation. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:425-440. |

| 14. | Turley SD, Dietschy JM. The metabolism and excretion of cholesterol by the liver. The liver: biology and pathobiology. New York: Raven Press 1988; 617-641. |

| 15. | Botham KM, Bravo E. The role of lipoprotein cholesterol in biliary steroid secretion. Studies with in vivo experimental models. Prog Lipid Res. 1995;34:71-97. |

| 16. | Schwartz CC, Halloran LG, Vlahcevic ZR, Gregory DH, Swell L. Preferential utilization of free cholesterol from high-density lipoproteins for biliary cholesterol secretion in man. Science. 1978;200:62-64. |

| 17. | Hillebrant CG, Nyberg B, Einarsson K, Eriksson M. The effect of plasma low density lipoprotein apheresis on the hepatic secretion of biliary lipids in humans. Gut. 1997;41:700-704. |

| 18. | Schwartz CC, Berman M, Vlahcevic ZR, Halloran LG, Gregory DH, Swell L. Multicompartmental analysis of cholesterol metabolism in man. Characterization of the hepatic bile acid and biliary cholesterol precursor sites. J Clin Invest. 1978;61:408-423. |

| 19. | Schwartz CC, Vlahcevic ZR, Halloran LG, Gregory DH, Meek JB, Swell L. Evidence for the existence of definitive hepatic cholesterol precursor compartments for bile acids and biliary cholesterol in man. Gastroenterology. 1975;69:1379-1382. |

| 20. | Groen AK, Bloks VW, Bandsma RH, Ottenhoff R, Chimini G, Kuipers F. Hepatobiliary cholesterol transport is not impaired in Abca1-null mice lacking HDL. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:843-850. |

| 21. | Ji Y, Wang N, Ramakrishnan R, Sehayek E, Huszar D, Breslow JL, Tall AR. Hepatic scavenger receptor BI promotes rapid clearance of high density lipoprotein free cholesterol and its transport into bile. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33398-33402. |

| 22. | Jolley CD, Dietschy JM, Turley SD. Induction of bile acid synthesis by cholesterol and cholestyramine feeding is unimpaired in mice deficient in apolipoprotein AI. Hepatology. 2000;32:1309-1316. |

| 23. | Lefebvre P, Cariou B, Lien F, Kuipers F, Staels B. Role of bile acids and bile acid receptors in metabolic regulation. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:147-191. |

| 24. | Hofmann AF. Bile acids: trying to understand their chemistry and biology with the hope of helping patients. Hepatology. 2009;49:1403-1418. |

| 25. | Björkhem I, Leoni V, Meaney S. Genetic connections between neurological disorders and cholesterol metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:2489-2503. |

| 26. | Peake KB, Vance JE. Defective cholesterol trafficking in Niemann-Pick C-deficient cells. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:2731-2739. |

| 27. | Amigo L, Mendoza H, Castro J, Quiñones V, Miquel JF, Zanlungo S. Relevance of Niemann-Pick type C1 protein expression in controlling plasma cholesterol and biliary lipid secretion in mice. Hepatology. 2002;36:819-828. |

| 28. | Storch J, Xu Z. Niemann-Pick C2 (NPC2) and intracellular cholesterol trafficking. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791:671-678. |

| 29. | Klein A, Amigo L, Retamal MJ, Morales MG, Miquel JF, Rigotti A, Zanlungo S. NPC2 is expressed in human and murine liver and secreted into bile: potential implications for body cholesterol homeostasis. Hepatology. 2006;43:126-133. |

| 30. | Zanlungo S, Amigo L, Mendoza H, Miquel JF, Vío C, Glick JM, Rodríguez A, Kozarsky K, Quiñones V, Rigotti A. Sterol carrier protein 2 gene transfer changes lipid metabolism and enterohepatic sterol circulation in mice. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1708-1719. |

| 31. | Amigo L, Zanlungo S, Miquel JF, Glick JM, Hyogo H, Cohen DE, Rigotti A, Nervi F. Hepatic overexpression of sterol carrier protein-2 inhibits VLDL production and reciprocally enhances biliary lipid secretion. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:399-407. |

| 32. | Puglielli L, Rigotti A, Amigo L, Nuñez L, Greco AV, Santos MJ, Nervi F. Modulation of intrahepatic cholesterol trafficking: evidence by in vivo antisense treatment for the involvement of sterol carrier protein-2 in newly synthesized cholesterol transport into rat bile. Biochem J. 1996;317:681-687. |

| 33. | Strauss JF 3rd, Kishida T, Christenson LK, Fujimoto T, Hiroi H. START domain proteins and the intracellular trafficking of cholesterol in steroidogenic cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;202:59-65. |

| 34. | Lavigne P, Najmanivich R, Lehoux JG. Mammalian StAR-related lipid transfer (START) domains with specificity for cholesterol: structural conservation and mechanism of reversible binding. Subcell Biochem. 2010;51:425-437. |

| 35. | Ren S, Hylemon PB, Marques D, Gurley E, Bodhan P, Hall E, Redford K, Gil G, Pandak WM. Overexpression of cholesterol transporter StAR increases in vivo rates of bile acid synthesis in the rat and mouse. Hepatology. 2004;40:910-917. |

| 36. | Kishida T, Kostetskii I, Zhang Z, Martinez F, Liu P, Walkley SU, Dwyer NK, Blanchette-Mackie EJ, Radice GL, Strauss JF 3rd. Targeted mutation of the MLN64 START domain causes only modest alterations in cellular sterol metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19276-19285. |

| 37. | Zhao B, Song J, Ghosh S. Hepatic overexpression of cholesteryl ester hydrolase enhances cholesterol elimination and in vivo reverse cholesterol transport. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:2212-2217. |

| 38. | Brown JM, Bell TA 3rd, Alger HM, Sawyer JK, Smith TL, Kelley K, Shah R, Wilson MD, Davis MA, Lee RG. Targeted depletion of hepatic ACAT2-driven cholesterol esterification reveals a non-biliary route for fecal neutral sterol loss. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10522-10534. |

| 39. | Fiévet C, Staels B. Liver X receptor modulators: effects on lipid metabolism and potential use in the treatment of atherosclerosis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;77:1316-1327. |

| 40. | Zelcer N, Tontonoz P. Liver X receptors as integrators of metabolic and inflammatory signaling. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:607-614. |

| 41. | Rader DJ. Liver X receptor and farnesoid X receptor as therapeutic targets. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:n15-n19. |

| 42. | Repa JJ, Berge KE, Pomajzl C, Richardson JA, Hobbs H, Mangelsdorf DJ. Regulation of ATP-binding cassette sterol transporters ABCG5 and ABCG8 by the liver X receptors alpha and beta. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:18793-18800. |

| 43. | Peet DJ, Turley SD, Ma W, Janowski BA, Lobaccaro JM, Hammer RE, Mangelsdorf DJ. Cholesterol and bile acid metabolism are impaired in mice lacking the nuclear oxysterol receptor LXR alpha. Cell. 1998;93:693-704. |

| 44. | Stieger B. Recent insights into the function and regulation of the bile salt export pump (ABCB11). Curr Opin Lipidol. 2009;20:176-181. |

| 45. | Oude Elferink RP, Groen AK. Mechanisms of biliary lipid secretion and their role in lipid homeostasis. Semin Liver Dis. 2000;20:293-305. |

| 46. | Oude Elferink RP, Paulusma CC, Groen AK. Hepatocanalicular transport defects: pathophysiologic mechanisms of rare diseases. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:908-925. |

| 47. | Smit JJ, Schinkel AH, Oude Elferink RP, Groen AK, Wagenaar E, van Deemter L, Mol CA, Ottenhoff R, van der Lugt NM, van Roon MA. Homozygous disruption of the murine mdr2 P-glycoprotein gene leads to a complete absence of phospholipid from bile and to liver disease. Cell. 1993;75:451-462. |

| 48. | Oude Elferink RP, Ottenhoff R, van Wijland M, Smit JJ, Schinkel AH, Groen AK. Regulation of biliary lipid secretion by mdr2 P-glycoprotein in the mouse. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:31-38. |

| 49. | Fickert P, Fuchsbichler A, Wagner M, Zollner G, Kaser A, Tilg H, Krause R, Lammert F, Langner C, Zatloukal K. Regurgitation of bile acids from leaky bile ducts causes sclerosing cholangitis in Mdr2 (Abcb4) knockout mice. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:261-274. |

| 50. | Mauad TH, van Nieuwkerk CM, Dingemans KP, Smit JJ, Schinkel AH, Notenboom RG, van den Bergh Weerman MA, Verkruisen RP, Groen AK, Oude Elferink RP. Mice with homozygous disruption of the mdr2 P-glycoprotein gene. A novel animal model for studies of nonsuppurative inflammatory cholangitis and hepatocarcinogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1994;145:1237-1245. |

| 51. | Paulusma CC, Groen A, Kunne C, Ho-Mok KS, Spijkerboer AL, Rudi de Waart D, Hoek FJ, Vreeling H, Hoeben KA, van Marle J. Atp8b1 deficiency in mice reduces resistance of the canalicular membrane to hydrophobic bile salts and impairs bile salt transport. Hepatology. 2006;44:195-204. |

| 52. | Groen A, Kunne C, Jongsma G, van den Oever K, Mok KS, Petruzzelli M, Vrins CL, Bull L, Paulusma CC, Oude Elferink RP. Abcg5/8 independent biliary cholesterol excretion in Atp8b1-deficient mice. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:2091-2100. |

| 53. | Bull LN, van Eijk MJ, Pawlikowska L, DeYoung JA, Juijn JA, Liao M, Klomp LW, Lomri N, Berger R, Scharschmidt BF. A gene encoding a P-type ATPase mutated in two forms of hereditary cholestasis. Nat Genet. 1998;18:219-224. |

| 54. | Klomp LW, Vargas JC, van Mil SW, Pawlikowska L, Strautnieks SS, van Eijk MJ, Juijn JA, Pabón-Peña C, Smith LB, DeYoung JA. Characterization of mutations in ATP8B1 associated with hereditary cholestasis. Hepatology. 2004;40:27-38. |

| 55. | Pawlikowska L, Groen A, Eppens EF, Kunne C, Ottenhoff R, Looije N, Knisely AS, Killeen NP, Bull LN, Elferink RP. A mouse genetic model for familial cholestasis caused by ATP8B1 mutations reveals perturbed bile salt homeostasis but no impairment in bile secretion. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:881-892. |

| 56. | Trauner M, Boyer JL. Bile salt transporters: molecular characterization, function, and regulation. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:633-671. |

| 57. | Wang HH, Lammert F, Schmitz A, Wang DQ. Transgenic overexpression of Abcb11 enhances biliary bile salt outputs, but does not affect cholesterol cholelithogenesis in mice. Eur J Clin Invest. 2010;40:541-551. |

| 58. | Wang R, Lam P, Liu L, Forrest D, Yousef IM, Mignault D, Phillips MJ, Ling V. Severe cholestasis induced by cholic acid feeding in knockout mice of sister of P-glycoprotein. Hepatology. 2003;38:1489-1499. |

| 59. | Wang R, Chen HL, Liu L, Sheps JA, Phillips MJ, Ling V. Compensatory role of P-glycoproteins in knockout mice lacking the bile salt export pump. Hepatology. 2009;50:948-956. |

| 60. | Oude Elferink RP, Paulusma CC. The Function of the Canalicular Membrane in Bile Formation and Secretion. 5th ed. Chichester, West Sussex, UK; Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons 2009; . |

| 61. | Simons K, Vaz WL. Model systems, lipid rafts, and cell membranes. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2004;33:269-295. |

| 62. | de Almeida RF, Fedorov A, Prieto M. Sphingomyelin/phosphatidylcholine/cholesterol phase diagram: boundaries and composition of lipid rafts. Biophys J. 2003;85:2406-2416. |

| 63. | Amigo L, Mendoza H, Zanlungo S, Miquel JF, Rigotti A, González S, Nervi F. Enrichment of canalicular membrane with cholesterol and sphingomyelin prevents bile salt-induced hepatic damage. J Lipid Res. 1999;40:533-542. |

| 64. | Schroeder RJ, Ahmed SN, Zhu Y, London E, Brown DA. Cholesterol and sphingolipid enhance the Triton X-100 insolubility of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins by promoting the formation of detergent-insoluble ordered membrane domains. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1150-1157. |

| 65. | Graf GA, Yu L, Li WP, Gerard R, Tuma PL, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. ABCG5 and ABCG8 are obligate heterodimers for protein trafficking and biliary cholesterol excretion. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:48275-48282. |

| 66. | Berge KE, Tian H, Graf GA, Yu L, Grishin NV, Schultz J, Kwiterovich P, Shan B, Barnes R, Hobbs HH. Accumulation of dietary cholesterol in sitosterolemia caused by mutations in adjacent ABC transporters. Science. 2000;290:1771-1775. |

| 67. | Graf GA, Li WP, Gerard RD, Gelissen I, White A, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Coexpression of ATP-binding cassette proteins ABCG5 and ABCG8 permits their transport to the apical surface. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:659-669. |

| 68. | Hazard SE, Patel SB. Sterolins ABCG5 and ABCG8: regulators of whole body dietary sterols. Pflugers Arch. 2007;453:745-752. |

| 69. | Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D. The metabolic and molecular bases of inherited disease. 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill 1995; . |

| 70. | Yu L, Li-Hawkins J, Hammer RE, Berge KE, Horton JD, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Overexpression of ABCG5 and ABCG8 promotes biliary cholesterol secretion and reduces fractional absorption of dietary cholesterol. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:671-680. |

| 71. | Yu L, Hammer RE, Li-Hawkins J, Von Bergmann K, Lutjohann D, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Disruption of Abcg5 and Abcg8 in mice reveals their crucial role in biliary cholesterol secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16237-16242. |

| 72. | Klett EL, Lu K, Kosters A, Vink E, Lee MH, Altenburg M, Shefer S, Batta AK, Yu H, Chen J. A mouse model of sitosterolemia: absence of Abcg8/sterolin-2 results in failure to secrete biliary cholesterol. BMC Med. 2004;2:5. |

| 73. | Plösch T, Bloks VW, Terasawa Y, Berdy S, Siegler K, Van Der Sluijs F, Kema IP, Groen AK, Shan B, Kuipers F. Sitosterolemia in ABC-transporter G5-deficient mice is aggravated on activation of the liver-X receptor. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:290-300. |

| 74. | Yu L, Gupta S, Xu F, Liverman AD, Moschetta A, Mangelsdorf DJ, Repa JJ, Hobbs HH, Cohen JC. Expression of ABCG5 and ABCG8 is required for regulation of biliary cholesterol secretion. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8742-8747. |

| 75. | Yu L, York J, von Bergmann K, Lutjohann D, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Stimulation of cholesterol excretion by the liver X receptor agonist requires ATP-binding cassette transporters G5 and G8. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15565-15570. |

| 76. | Kosters A, Frijters RJ, Kunne C, Vink E, Schneiders MS, Schaap FG, Nibbering CP, Patel SB, Groen AK. Diosgenin-induced biliary cholesterol secretion in mice requires Abcg8. Hepatology. 2005;41:141-150. |

| 77. | Plösch T, van der Veen JN, Havinga R, Huijkman NC, Bloks VW, Kuipers F. Abcg5/Abcg8-independent pathways contribute to hepatobiliary cholesterol secretion in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G414-G423. |

| 78. | Wilund KR, Yu L, Xu F, Hobbs HH, Cohen JC. High-level expression of ABCG5 and ABCG8 attenuates diet-induced hypercholesterolemia and atherosclerosis in Ldlr-/- mice. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:1429-1436. |

| 79. | Wu JE, Basso F, Shamburek RD, Amar MJ, Vaisman B, Szakacs G, Joyce C, Tansey T, Freeman L, Paigen BJ. Hepatic ABCG5 and ABCG8 overexpression increases hepatobiliary sterol transport but does not alter aortic atherosclerosis in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22913-22925. |

| 80. | Basso F, Freeman LA, Ko C, Joyce C, Amar MJ, Shamburek RD, Tansey T, Thomas F, Wu J, Paigen B. Hepatic ABCG5/G8 overexpression reduces apoB-lipoproteins and atherosclerosis when cholesterol absorption is inhibited. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:114-126. |

| 81. | Katsika D, Magnusson P, Krawczyk M, Grünhage F, Lichtenstein P, Einarsson C, Lammert F, Marschall HU. Gallstone disease in Swedish twins: risk is associated with ABCG8 D19H genotype. J Intern Med. 2010;268:279-285. |

| 82. | Buch S, Schafmayer C, Völzke H, Becker C, Franke A, von Eller-Eberstein H, Kluck C, Bässmann I, Brosch M, Lammert F. A genome-wide association scan identifies the hepatic cholesterol transporter ABCG8 as a susceptibility factor for human gallstone disease. Nat Genet. 2007;39:995-999. |

| 83. | Grünhage F, Acalovschi M, Tirziu S, Walier M, Wienker TF, Ciocan A, Mosteanu O, Sauerbruch T, Lammert F. Increased gallstone risk in humans conferred by common variant of hepatic ATP-binding cassette transporter for cholesterol. Hepatology. 2007;46:793-801. |

| 84. | Small DM. Role of ABC transporters in secretion of cholesterol from liver into bile. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:4-6. |

| 85. | Altmann SW, Davis HR Jr, Zhu LJ, Yao X, Hoos LM, Tetzloff G, Iyer SP, Maguire M, Golovko A, Zeng M. Niemann-Pick C1 Like 1 protein is critical for intestinal cholesterol absorption. Science. 2004;303:1201-1204. |

| 86. | Davis HR Jr, Zhu LJ, Hoos LM, Tetzloff G, Maguire M, Liu J, Yao X, Iyer SP, Lam MH, Lund EG. Niemann-Pick C1 Like 1 (NPC1L1) is the intestinal phytosterol and cholesterol transporter and a key modulator of whole-body cholesterol homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:33586-33592. |

| 87. | Pramfalk C, Jiang ZY, Cai Q, Hu H, Zhang SD, Han TQ, Eriksson M, Parini P. HNF1alpha and SREBP2 are important regulators of NPC1L1 in human liver. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:1354-1362. |

| 88. | Brown JM, Yu L. Opposing Gatekeepers of Apical Sterol Transport: Niemann-Pick C1-Like 1 (NPC1L1) and ATP-Binding Cassette Transporters G5 and G8 (ABCG5/ABCG8). Immunol Endocr Metab Agents Med Chem. 2009;9:18-29. |

| 89. | Temel RE, Tang W, Ma Y, Rudel LL, Willingham MC, Ioannou YA, Davies JP, Nilsson LM, Yu L. Hepatic Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 regulates biliary cholesterol concentration and is a target of ezetimibe. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1968-1978. |

| 90. | Trigatti BL, Krieger M, Rigotti A. Influence of the HDL receptor SR-BI on lipoprotein metabolism and atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1732-1738. |

| 91. | Rhainds D, Brissette L. The role of scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI) in lipid trafficking. defining the rules for lipid traders. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:39-77. |

| 92. | Kozarsky KF, Donahee MH, Rigotti A, Iqbal SN, Edelman ER, Krieger M. Overexpression of the HDL receptor SR-BI alters plasma HDL and bile cholesterol levels. Nature. 1997;387:414-417. |

| 93. | Wiersma H, Gatti A, Nijstad N, Oude Elferink RP, Kuipers F, Tietge UJ. Scavenger receptor class B type I mediates biliary cholesterol secretion independent of ATP-binding cassette transporter g5/g8 in mice. Hepatology. 2009;50:1263-1272. |

| 94. | Tietge UJ, Nijstad N, Havinga R, Baller JF, van der Sluijs FH, Bloks VW, Gautier T, Kuipers F. Secretory phospholipase A2 increases SR-BI-mediated selective uptake from HDL but not biliary cholesterol secretion. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:563-571. |

| 95. | Jin W, Marchadier D, Rader DJ. Lipases and HDL metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2002;13:174-178. |

| 96. | Broedl UC, Jin W, Rader DJ. Endothelial lipase: a modulator of lipoprotein metabolism upregulated by inflammation. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2004;14:202-206. |

| 97. | Nijstad N, Wiersma H, Gautier T, van der Giet M, Maugeais C, Tietge UJ. Scavenger receptor BI-mediated selective uptake is required for the remodeling of high density lipoprotein by endothelial lipase. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6093-6100. |

| 98. | Jönsson-Rylander AC, Lundin S, Rosengren B, Pettersson C, Hurt-Camejo E. Role of secretory phospholipases in atherogenesis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2008;10:252-259. |

| 99. | Webb NR. Secretory phospholipase A2 enzymes in atherogenesis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2005;16:341-344. |

| 100. | Maugeais C, Tietge UJ, Broedl UC, Marchadier D, Cain W, McCoy MG, Lund-Katz S, Glick JM, Rader DJ. Dose-dependent acceleration of high-density lipoprotein catabolism by endothelial lipase. Circulation. 2003;108:2121-2126. |

| 101. | Wiersma H, Gatti A, Nijstad N, Kuipers F, Tietge UJ. Hepatic SR-BI, not endothelial lipase, expression determines biliary cholesterol secretion in mice. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:1571-1580. |

| 102. | Amigo L, Mardones P, Ferrada C, Zanlungo S, Nervi F, Miquel JF, Rigotti A. Biliary lipid secretion, bile acid metabolism, and gallstone formation are not impaired in hepatic lipase-deficient mice. Hepatology. 2003;38:726-734. |

| 103. | Mardones P, Quiñones V, Amigo L, Moreno M, Miquel JF, Schwarz M, Miettinen HE, Trigatti B, Krieger M, VanPatten S. Hepatic cholesterol and bile acid metabolism and intestinal cholesterol absorption in scavenger receptor class B type I-deficient mice. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:170-180. |

| 104. | Zhang Y, Da Silva JR, Reilly M, Billheimer JT, Rothblat GH, Rader DJ. Hepatic expression of scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI) is a positive regulator of macrophage reverse cholesterol transport in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2870-2874. |

| 105. | Kozarsky KF, Donahee MH, Glick JM, Krieger M, Rader DJ. Gene transfer and hepatic overexpression of the HDL receptor SR-BI reduces atherosclerosis in the cholesterol-fed LDL receptor-deficient mouse. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:721-727. |

| 106. | Arai T, Wang N, Bezouevski M, Welch C, Tall AR. Decreased atherosclerosis in heterozygous low density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice expressing the scavenger receptor BI transgene. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2366-2371. |

| 107. | Fuchs M, Ivandic B, Müller O, Schalla C, Scheibner J, Bartsch P, Stange EF. Biliary cholesterol hypersecretion in gallstone-susceptible mice is associated with hepatic up-regulation of the high-density lipoprotein receptor SRBI. Hepatology. 2001;33:1451-1459. |

| 108. | Jiang ZY, Parini P, Eggertsen G, Davis MA, Hu H, Suo GJ, Zhang SD, Rudel LL, Han TQ, Einarsson C. Increased expression of LXR alpha, ABCG5, ABCG8, and SR-BI in the liver from normolipidemic, nonobese Chinese gallstone patients. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:464-472. |

| 109. | Van Eck M, Twisk J, Hoekstra M, Van Rij BT, Van der Lans CA, Bos IS, Kruijt JK, Kuipers F, Van Berkel TJ. Differential effects of scavenger receptor BI deficiency on lipid metabolism in cells of the arterial wall and in the liver. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:23699-23705. |

| 110. | Silver DL, Tall AR. The cellular biology of scavenger receptor class B type I. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2001;12:497-504. |

| 111. | Malaval C, Laffargue M, Barbaras R, Rolland C, Peres C, Champagne E, Perret B, Tercé F, Collet X, Martinez LO. RhoA/ROCK I signalling downstream of the P2Y13 ADP-receptor controls HDL endocytosis in human hepatocytes. Cell Signal. 2009;21:120-127. |

| 112. | Martinez LO, Jacquet S, Esteve JP, Rolland C, Cabezón E, Champagne E, Pineau T, Georgeaud V, Walker JE, Tercé F. Ectopic beta-chain of ATP synthase is an apolipoprotein A-I receptor in hepatic HDL endocytosis. Nature. 2003;421:75-79. |

| 113. | Tietge UJ, Maugeais C, Cain W, Grass D, Glick JM, de Beer FC, Rader DJ. Overexpression of secretory phospholipase A(2) causes rapid catabolism and altered tissue uptake of high density lipoprotein cholesteryl ester and apolipoprotein A-I. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:10077-10084. |

| 114. | Tietge UJ, Maugeais C, Cain W, Rader DJ. Acute inflammation increases selective uptake of HDL cholesteryl esters into adrenals of mice overexpressing human sPLA2. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;285:E403-E411. |

Peer reviewers: Gustav Paumgartner, Professor, University of Munich, Klinikum Grosshadern, Marchioninistrasse 15, Munich, D-81377, Germany; Eldon Shaffer, Professor of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Health Science Centre, University of Calgary, 3330 Hospital Dr N.W., Calgary, AB, T2N4N1, Canada

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Zheng XM