Published online Nov 7, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i41.5211

Revised: May 11, 2010

Accepted: May 18, 2010

Published online: November 7, 2010

AIM: To analyse the influence of Smad7, antagonist of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β canonical signaling pathways on hepatic stellate cell (HSC) transdifferentiation in detail.

METHODS: We systematically analysed genes regulated by TGF-β/Smad7 in activated HSCs by microarray analysis and validated the results using real time polymerase chain reaction and Western blotting analysis.

RESULTS: We identified 100 known and unknown targets underlying the regulation of Smad7 expression and delineated 8 gene ontology groups. Hk2, involved in glycolysis, was one of the most downregulated proteins, while BMP2, activator of the Smad1/5/8 pathway, was extremely upregulated by Smad7. However, BMP2 dependent Smad1 activation could be inhibited in vitro by Smad7 overexpression in HSCs.

CONCLUSION: We conclude (1) the existence of a tight crosstalk of TGF-β and BMP2 pathways in HSCs and (2) a Smad7 dependently decreased sugar metabolism ameliorates HSC activation probably by energy withdrawal.

- Citation: Denecke B, Wickert L, Liu Y, Ciuclan L, Dooley S, Meindl-Beinker NM. Smad7 dependent expression signature highlights BMP2 and HK2 signaling in HSC transdifferentiation. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(41): 5211-5224

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i41/5211.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i41.5211

Histopathological changes of chronic liver diseases usually start with inflammatory hepatitis, followed by fibrosis and the final stage of cirrhosis, possibly leading to liver cancer. Hepatic fibrosis is characterized by increased and altered deposition of newly generated or deficiently degraded extracellular matrix (ECM) in response to injury[1]. Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) are the major fibrotic precursor cells that transdifferentiate in inflammatory liver tissue to fibrogenic myofibroblasts (MFBs), by undergoing morphological changes, increased expression of α-SMA and synthesis of large amounts of ECM components[2].

Transdifferentiation of HSCs is driven by a variety of cytokines with transforming growth factor (TGF)-β playing a master role. It stimulates quiescent HSCs by paracrine and transdifferentiated MFBs by autocrine mechanisms activating intracellular Smad cascades. A great variety of cytokines, chemokines and mitogens (TNF-α, IFN-γ, EGF, PDGF, CTGF, ID1, YB1) display complex crosstalk with TGF-β[3-6].

Smad7 is a powerful antagonist of TGF-β in HSCs blunting downstream signaling by inhibiting receptor (R)-Smad phosphorylation[7]. In quiescent HSCs, expression of Smad7 itself is induced by the R-Smad cascade, thereby providing a negative feedback loop to terminate TGF-β signals[8]. We demonstrated before phenotypically and functionally that overexpressed Smad7 inhibits HSC transdifferentiation and attenuates the extent of fibrosis[7] suggesting that Smad7 is a promising antifibrotic tool for treatment approaches.

Therefore, in this study we analyzed the influence of Smad7 on the HSC gene expression pattern in great detail using microarray analysis. Its overexpression affects a great variety of cellular pathways involved in development, angiogenesis, differentiation, transcription, immune response, apoptosis, proliferation, signal transduction, ion and electron transport, sugar and lipid metabolism, morphogenesis, protein synthesis and modification, DNA synthesis and repair, cell adhesion, stress response, blood circulation, cell cycle and growth, cell motility, muscle contraction and organization of the cytoskeleton. The strongest regulated proteins are Pla2g2a, Cyp4b1, both upregulated and, Hk2 and VEGFa, which were downregulated significantly. Interestingly, BMP2, a member of the TGF-β family and alternative activator of the Smad1/5/8 pathway, was strongly induced by Smad7 overexpression in HSCs.

Primary HSCs of male Sprague-Dawley were isolated as previously described[9,10]. To identify Smad7 dependent gene responses, HSCs were infected with adenoviruses encoding for Smad7 (AdSmad7; kindly provided by C. Heldin (Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Uppsala, Sweden)) or LacZ (AdLacZ) as control 2 d after seeding[7].

RNA sample collection and generation of biotinylated complementary RNA probes was carried out according to the Affymetrix GeneChip® Expression Analysis Technical Manual (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA,USA). In brief, total RNA was prepared at day 4 from 5 × 106 cultured primary HSCs that were infected with AdLacZ or AdSmad7 at day 2. Twenty five micrograms total RNA was reversely transcribed into double-stranded cDNA using HPLC-purified T7-(dt) 24 primers (MWG, Ebersberg, Germany) and the Superscript choice cDNA synthesis system (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA). Purified cDNA was used to synthesize biotinylated complementary RNA using the BioArray High Yield RNA Transcription Labeling Kit (Enzo Diagnostics, Enzo Life Science Inc., Farmingdale, NY, USA). Each sample was hybridized to an Affymetrix rat Genome RG-U34A microarray (8799 probe sets) for 16h at 45°C. Expression values of each probe set were determined and AdSmad7 infected samples were compared to AdLacZ infected controls using the Affymetrix Microarray Suite 5.0 software.

Intensities across multiple arrays were normalized to a target intensity of 2500 using global normalization scaling. Two separate experiments with HSCs from different animals were performed under identical conditions. Genes whose expression levels were changed more than 2-fold with P < 0.001 in both experiments were considered to be significantly regulated by Smad7. These genes were investigated according to their molecular function and biological process by searching the gene ontology (GO) term database. Genes differentially expressed in AdSmad7 treated compared to controls were classified by “pathway” analysis [KEGG (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html), PathwayArchitect, Stratagene].

Total RNA was collected from 3 (3 d-) or 7 d old (7 d-)HSCs, which were either infected with AdSmad7 or AdLacZ 2 d earlier or were uninfected[11]. cDNA from cell culture samples was synthesized as described[11]. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was performed as in[11] with modified conditions: 95°C for 60 s, then 40 cycles (50 cycles for low copy genes) of 95°C for 10 s, 60°C for 10 s and 72°C for 15 s. Annealing temperature was set at 58°C for U92564 and 62°C for rat VEGF.1. Primers are listed in Table 1. The quantity of target mRNA was determined using a TGF-β RI standard curve[11]: A cDNA fragment was amplified and column-purified using the QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and the following primers: TGFβ RI (GI: 416397) 180 bp; F (5'-CGTCTGCATTGCACTTATGC-3'), R (5'-AGCAGTGGTAAACCTGATCC-3'). A standard curve was generated from serial 10 time logarithmic dilutions of the cRNA by reverse transcription.

| Gene | Probe set ID | Forward | Reverse |

| CYP4B1 | M29853 | 5'CCGAAGGCTGCAGATGTGT3' | 5'TTTGGCCCATCCAGAACTAGTAG3' |

| mSmad7 | 5'GGTGCTCAAGAAACTCAAGG3' | 5'CAGCCTGCAGTCCAGGCG3' | |

| BMP2 | L02678_at | 5'TGCCCCCTAGTGCTTCTTAGAC3' | 5'GGGAAGCAGCAACACTAGAAGAC3' |

| SGIII | U02983 | 5'CAAGCAGGACCGAGAATCAG3' | 5'CGTTGGACAAGGTCAAGGTG3' |

| Zfp423 | U92564 | 5'GCAGTGCTACACCTGACTCG3' | 5'GTCATCCCGCATCTTCTTCTG3' |

| Pla2g2a | x51529 | 5'GCTCAATTCAGGTCCAGGG3' | 5'CCACCCACACCACAATGG3' |

| EST189231 | AA799734 | 5'CGGCTCACTGAGCTTGAAGTAG3' | 5'ACACGACGGAGGAGCTTCTG3' |

| Olr1 | AB005900 | 5'CAGAGAGAACTGAAGGAACAG3' | 5'GGACCTGAAGAGTTTGCAGC3' |

| ID1 | L23148_g_at | 5'TGGACGAACAGCAGGTGAAC3' | 5'TCTCCACCTTGCTCACTTTGC3' |

| HK2 | D26393exon_s_at | 5'CTCAGAGCGCCTCAAGACAAG3' | 5'GATGGCACGAACCTGTAGCA3' |

| Slc16a3 | U87627 | 5'CTCATCGGACCCCCATCAG3' | 5'CGCCAGGATGAACACATACTTG3' |

| ratVEGF.1 | 5'TGCCAAGTGGTCCCAGGC3' | 5'ATTGGACGGCAATAGCTGCG3' |

Isolated primary HSCs of female Wistar rats were cultured as in[7]. Following overnight starvation (0.5% FCS) HSCs were stimulated with 5 ng/mL human recombinant TGF-β (Peprotech, Hamburg, Germany) or 20 ng/mL BMP2 (R&D, Minneapolis, MN), respectively.

For Smad7 overexpression studies, HSCs were infected on day 3 or day 6 with 50 IFU/cell (infectious units) Smad7 encoding adenovirus for 24 hr in medium containing 5% FBS. Four days old HSCs are considered to be in the transactivation process, while 7 d old HSCs are considered to be fully activated. After infection cells were serum-starved overnight and stimulated with 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 or 20 ng/mL BMP2. Generally, more than 90% of HSCs were infected.

For Western blotting analysis 20 μg protein was separated (4%-12% Bis-Tris Gel, NuPAGE, Invitrogen) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Nonspecific binding was blocked with 5% milk/TBST for Smad7 and GAPDH (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) or 5% BSA/TBST for pSmad1/3 antibodies (Epitomics/Biomol). Horseradish peroxidase-linked goat anti-rabbit antibody (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) served as secondary antibody. Membranes were developed with Supersignal Ultra (Pierce, Hamburg, Germany).

At day 2 of culture, primary rat HSCs were infected with AdSmad7 or AdLacZ (control). Two days later, when HSCs are in the process of transdifferentiation, the expression of genes displayed on 8799 probe sets was compared between cells overexpressing Smad7 and controls. Confirming Western blotting analysis of HSC lysates[12], microarray data revealed tremendous overexpression of Smad7 in AdSmad7 infected HSCs (40.79 times).

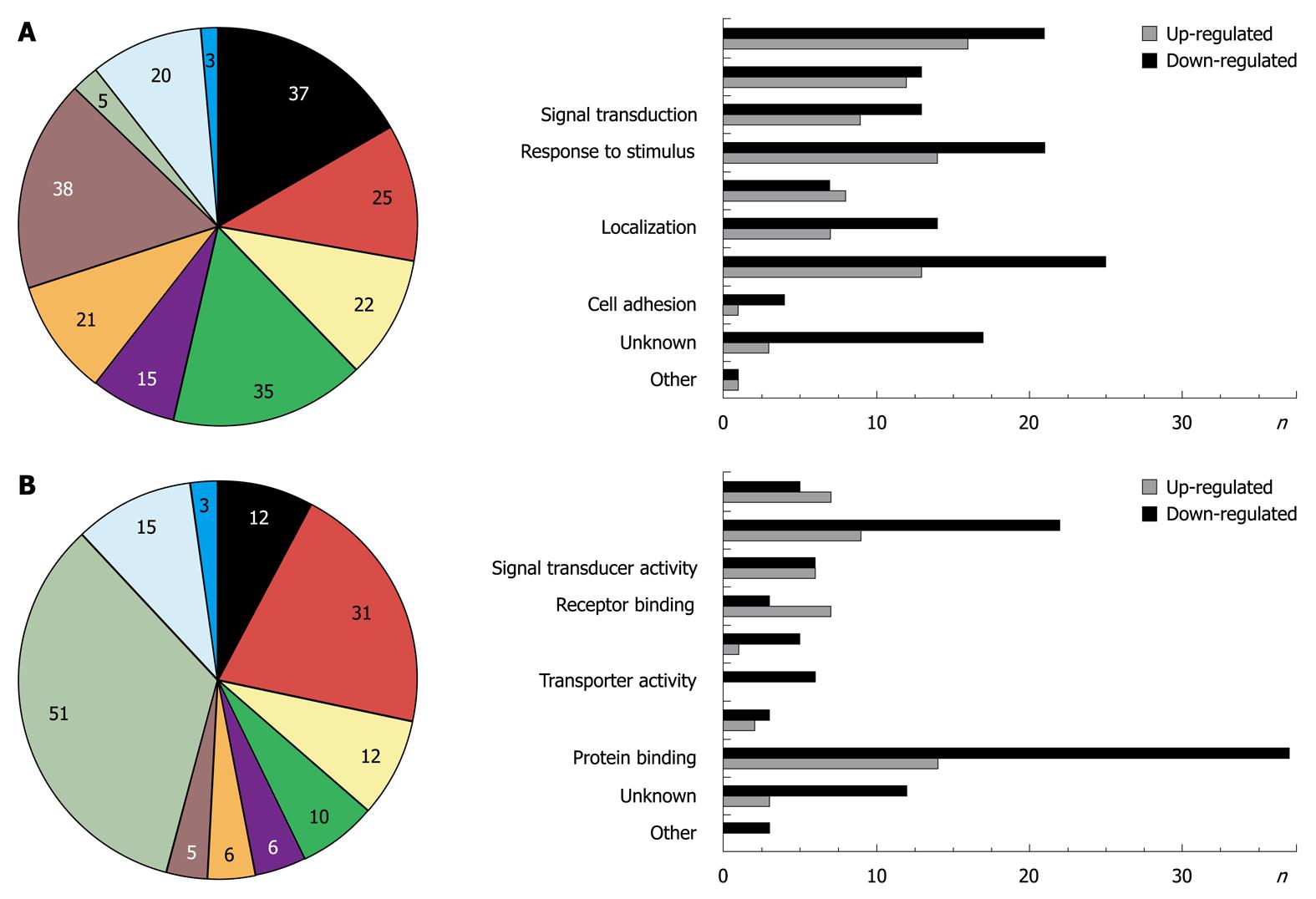

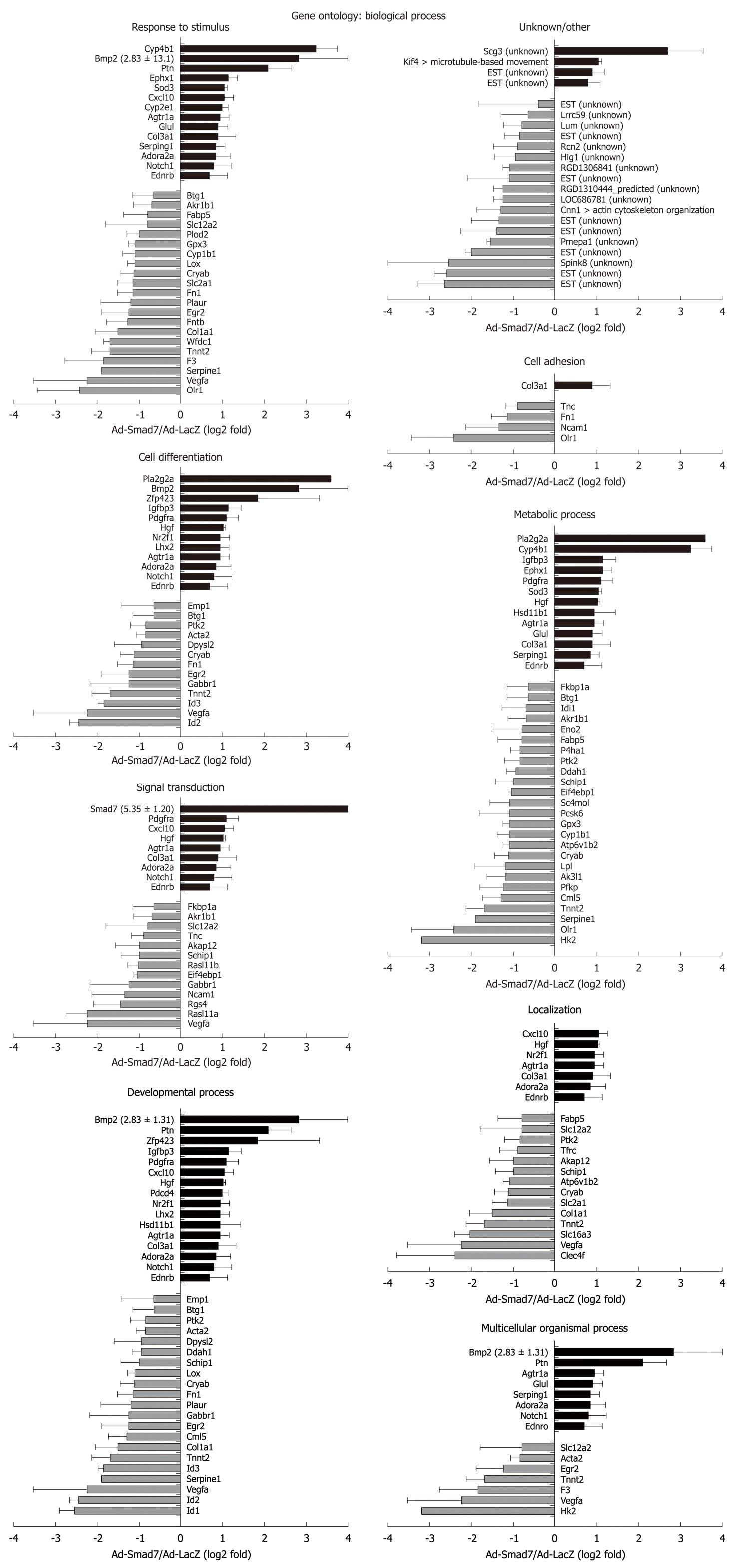

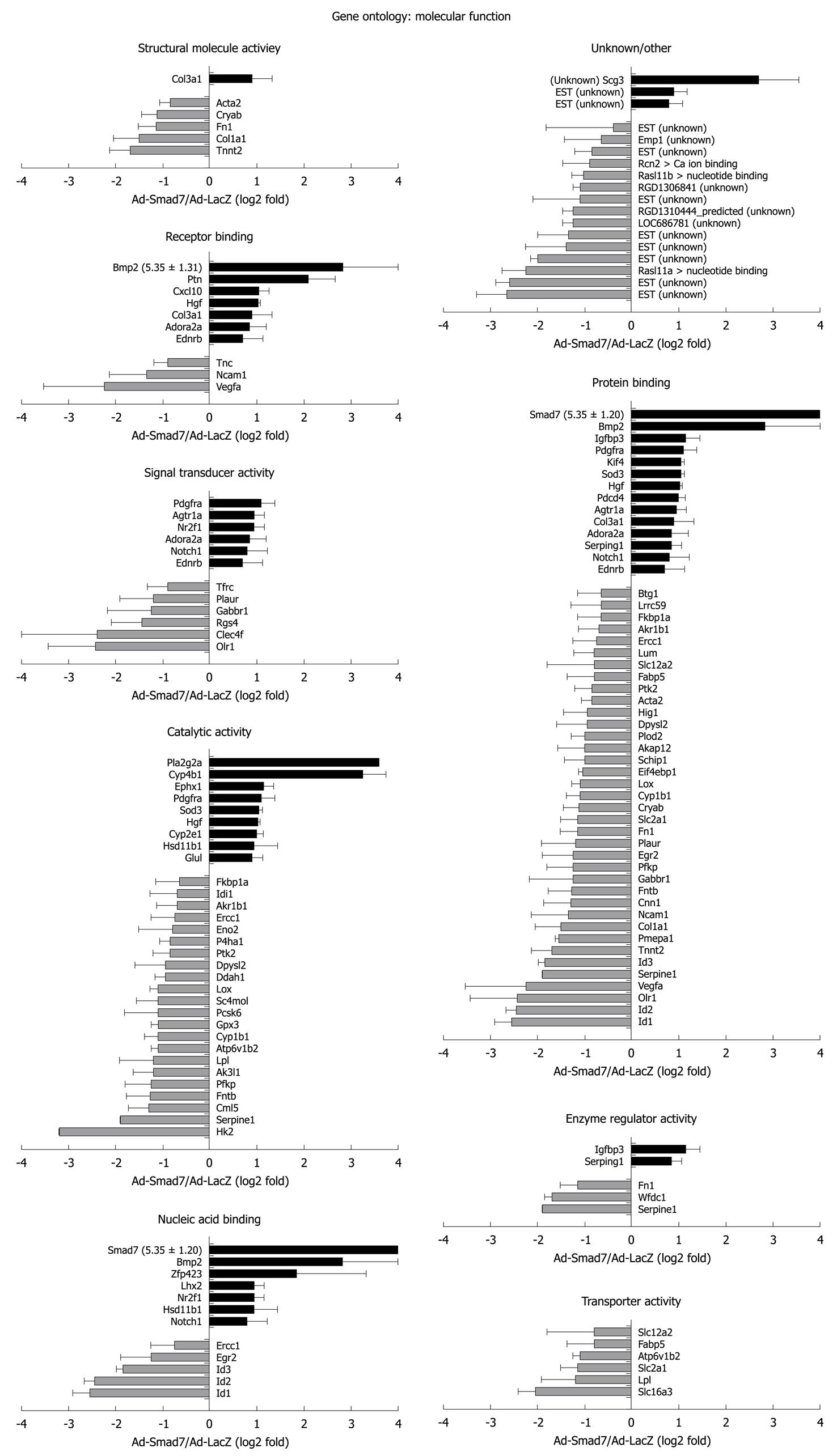

One hundred and twenty-nine probe sets were found differentially expressed due to Smad7, including 10 unknown proteins, 1 predicted protein and 89 known proteins (Table 2 provides a full list). According to their biological role, these genes were classified into eight main GO groups (Figure 1A). 37% of the regulated genes are involved in development. 22% can be assigned to signal transduction processes, which was expected since Smad7 represses TGF-β signaling and thus has impact on manifold different cross-talking signaling pathways. 15% refer to multicellular organismal processes (i.e. processes involved in intercellular interaction of any kind), 35% to response to stimulus, 21% to localization, 38% to metabolic processes, 25% to cell differentiation and 5% to cell adhesion. Note that the total percentage is greater than 100% as some regulated genes can be assigned to different ontology groups. A similar classification of all differentially expressed genes was carried out according to their molecular function (Figure 1B). Figures 2 and 3 graphically summarize regulation of all genes according to their ontology groups.

| Official symbol | Average log2 fold | SD log2 fold | Affymetrix probe set ID | Official full name |

| Downregulated (n = 72) | ||||

| Acta2 | -0.85 | 0.21 | X06801cds_i_at | Smooth muscle α-actin |

| Ak3l1 | -1.20 | 0.42 | rc_AA891949_at | Adenylate kinase 3-like 1 |

| Akap12 | -1.00 | 0.57 | U75404UTR#1_s_at | A kinase (PRKA) anchor protein (gravin) 12 |

| Akr1b1 | -0.70 | 0.42 | M60322_g_at | Aldo-keto reductase family 1, member B1 (aldose reductase) |

| Atp6v1b2 | -1.10 | 0.14 | Y12635_at | ATPase, H transporting, lysosomal V1 subunit B2 |

| Btg1 | -0.65 | 0.49 | L26268_g_at | B-cell translocation gene 1, anti-proliferative |

| Clec4f | -2.40 | 3.39 | M55532_at | C-type lectin domain family 4, member f |

| Cml5 | -1.30 | 0.42 | rc_AA894273_at | Camello-like 5 |

| Cnn1 | -1.30 | 0.57 | D14437_s_at | Calponin 1 |

| Col1a1 | -1.51 | 0.53 | M27207mRNA_s_at/rc_AI231472_s_at/U75405UTR#1_f_at/Z78279_at/Z78279_g_at | Procollagen, type 1, α 1 |

| Cryab | -1.13 | 0.32 | M55534mRNA_s_at/X60351cds_s_at | Crystallin, α B |

| Cyp1b1 | -1.10 | 0.28 | rc_AI176856_at/U09540_at/U09540_g_at | Cytochrome P450, family 1, subfamily b, polypeptide 1 |

| Ddah1 | -0.95 | 0.21 | D86041_at | Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 1 |

| Dpysl2 | -0.95 | 0.64 | rc_AA875444_at | Dihydropyrimidinase-like 2 |

| Egr2 | -1.25 | 0.64 | U78102_at | Early growth response 2 |

| Eif4ebp1 | -1.05 | 0.07 | U05014_at | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 |

| Emp1 | -0.65 | 0.78 | Z54212_at | Epithelial membrane protein 1 |

| Eno2 | -0.80 | 0.71 | X07729exon#5_s_at | Enolase 2, γ |

| Ercc1 | -0.75 | 0.49 | rc_AA892791_at | Excision repair cross-complementing rodent repair deficiency, complementation group 1 |

| EST (unknown) | -2.65 | 0.64 | rc_AI102814_at | EST |

| EST (unknown) | -2.60 | 0.28 | rc_AI230256_at | EST |

| EST (unknown) | -2.00 | 0.14 | rc_AA874889_g_at | EST |

| EST (unknown) | -1.40 | 0.85 | rc_AA866419_at | EST |

| EST (unknown) | -1.35 | 0.64 | X62950mRNA_f_at | EST |

| EST (unknown) | -1.10 | 0.99 | rc_AA859740_at | EST |

| EST (unknown) | -0.85 | 0.35 | rc_AA800708_at | EST |

| EST (unknown) | -0.40 | 1.41 | X62951mRNA_s_at | EST |

| F3 | -1.85 | 0.92 | U07619_at | Coagulation factor III |

| Fabp5 | -0.80 | 0.57 | S69874_s_at | Fatty acid binding protein 5, epidermal |

| Fkbp1a | -0.65 | 0.49 | rc_AI228738_s_at | FK506 binding protein 1a |

| Fn1 | -1.15 | 0.36 | L00190cds#1_s_at/U82612cds_g_at/X05834_at | Fibronectin 1 |

| Fntb | -1.28 | 0.49 | rc_AI136396_at/rc_AI230914_at | Farnesyltransferase, CAAX box, β |

| Gabbr1 | -1.25 | 0.92 | rc_AI639395_at | γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) B receptor 1 |

| Gpx3 | -1.10 | 0.14 | D00680_at | Glutathione peroxidase 3 |

| Hig1 | -0.95 | 0.49 | rc_AA891422_at | Hypoxia induced gene 1 |

| Hk2 | -3.20 | 0.00 | D26393exon_s_at | Hexokinase 2 |

| Id1 | -2.55 | 0.35 | L23148_g_at | Inhibitor of DNA binding 1 |

| Id2 | -2.45 | 0.21 | rc_AI137583_at | Inhibitor of DNA binding 2 |

| Id3 | -1.85 | 0.13 | AF000942_at/rc_AI009405_s_at | Inhibitor of DNA binding 3 |

| Idi1 | -0.70 | 0.57 | AF003835_at | Isopentenyl-diphosphate delta isomerase |

| LOC686781 | -1.25 | 0.21 | rc_AA799657_at | Similar to NFκB interacting protein 1 |

| Lox | -1.10 | 0.17 | rc_AA875582_at/rc_AI234060_s_at/S77494_s_at | Lysyl oxidase |

| Lpl | -1.20 | 0.71 | L03294_at/L03294_g_at/rc_AI237731_s_at | Lipoprotein lipase |

| Lrrc59 | -0.65 | 0.64 | D13623_at | Leucine rich repeat containing 59 |

| Lum | -0.80 | 0.42 | X84039_at | Lumican |

| Ncam1 | -1.35 | 0.78 | X06564_at | Neural cell adhesion molecule 1 |

| Olr1 | -2.43 | 0.99 | AB005900_at/AB018104cds_s_at/rc_AI071531_s_at | Oxidized low density lipoprotein (lectin-like) receptor 1 |

| P4ha1 | -0.85 | 0.21 | X78949_at | Procollagen-proline, 2-oxoglutarate 4-dioxygenase (proline 4-hydroxylase), α 1 polypeptide |

| Pcsk6 | -1.10 | 0.71 | rc_AI230712_at | Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 6 |

| Pfkp | -1.25 | 0.54 | L25387_at/L25387_g_at | Phosphofructokinase, platelet |

| Plaur | -1.20 | 0.71 | X71898_at | Plasminogen activator, urokinase receptor |

| Plod2 | -1.00 | 0.28 | rc_AA892897_at | Procollagen lysine, 2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 2 |

| Pmepa1 | -1.55 | 0.07 | rc_AI639058_s_at | Prostate transmembrane protein, androgen induced 1 |

| Ptk2 | -0.85 | 0.35 | S83358_s_at | PTK2 protein tyrosine kinase 2 |

| Rasl11a | -2.25 | 0.49 | rc_AI169372_at | RAS-like family 11 member A |

| Rasl11b | -1.03 | 0.24 | rc_AA800853_at/rc_AA800853_g_at | RAS-like family 11 member B |

| Rcn2 | -0.90 | 0.57 | U15734_at | Reticulocalbin 2 |

| RGD1306841 | -1.10 | 0.14 | rc_AI639203_at | Similar to RIKEN cDNA 2410006F12 |

| RGD1310444_predicted | -1.25 | 0.21 | rc_AA866432_at | LOC363015 (predicted) |

| Rgs4 | -1.45 | 0.64 | U27767_at | Regulator of G-protein signaling 4 |

| Sc4mol | -1.10 | 0.45 | E12625cds_at/rc_AI172293_at | Sterol-C4-methyl oxidase-like |

| Schip1 | -1.00 | 0.42 | rc_AA800036_at | Schwannomin interacting protein 1 |

| Serpine1 | -1.90 | 0.00 | M24067_at | Serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade E, member 1 |

| Slc12a2 | -0.80 | 0.99 | AF051561_s_at | Solute carrier family 12, member 2 |

| Slc16a3 | -2.05 | 0.35 | U87627_at | Solute carrier family 16 (monocarboxylic acid transporters), member 3 |

| Slc2a1 | -1.15 | 0.35 | S68135_s_at | Solute carrier family 2 (facilitated glucose transporter), member 1 |

| Spink8 | -2.55 | 1.48 | rc_AA799734_at | Serine peptidase inhibitor, kazal type 8 |

| Tfrc | -0.90 | 0.42 | M58040_at | Transferrin receptor |

| Tnc | -0.90 | 0.28 | U09401_s_at | Tenascin C |

| Tnnt2 | -1.70 | 0.42 | M80829_at | Troponin T2, cardiac |

| Vegfa | -2.25 | 1.28 | L20913_s_at/M32167_g_at/rc_AA850734_at | Vascular endothelial growth factor A |

| Wfdc1 | -1.70 | 0.14 | AF037272_at | WAP four-disulfide core domain 1 |

| Up-regulated (n = 28) | ||||

| Adora2a | 0.85 | 0.35 | S47609_s_at | Adenosine A2a receptor |

| Agtr1a | 0.95 | 0.21 | M74054_s_at/X62295cds_s_at | Angiotensin II receptor, type 1 (AT1A) |

| Bmp2 | 2.83 | 1.31 | L02678_at/rc_AA997410_s_at | Bone morphogenetic protein 2 |

| Col3a1 | 0.90 | 0.42 | M21354_s_at/X70369_s_at/ | Procollagen, type III, α 1 |

| Cxcl10 | 1.05 | 0.21 | U17035_s_at | Chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 |

| Cyp2e1 | 1.00 | 0.14 | M20131cds_s_at | Cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily e, polypeptide 1 |

| Cyp4b1 | 3.25 | 0.49 | M29853_at | Cytochrome P450, family 4, subfamily b, polypeptide 1 |

| Ednrb | 0.70 | 0.42 | rc_AA818970_s_at | Endothelin receptor type B |

| Ephx1 | 1.15 | 0.21 | M26125_at | Epoxide hydrolase 1, microsomal |

| EST (unknown) | 0.80 | 0.28 | rc_AA874873_g_at | EST |

| EST (unknown) | 0.90 | 0.28 | rc_AI177256_at | EST |

| Glul | 0.90 | 0.23 | M91652complete_seq_at/rc_AA852004_s_at | Glutamate-ammonia ligase (glutamine synthase) |

| Hgf | 1.03 | 0.05 | E03190cds_s_at/X54400_r_at | Hepatocyte growth factor |

| Hsd11b1 | 0.95 | 0.49 | rc_AI105448_at | Hydroxysteroid 11-β dehydrogenase 1 |

| Igfbp3 | 1.15 | 0.30 | M31837_at | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 |

| Kif4 | 1.05 | 0.07 | rc_AA859926_at | Kinesin family member 4 |

| Lhx2 | 0.95 | 0.21 | L06804_at | LIM homeobox protein 2 |

| Notch1 | 0.80 | 0.42 | X57405_g_at | Notch gene homolog 1 (Drosophila) |

| Nr2f1 | 0.95 | 0.21 | U10995_g_at | Nuclear receptor subfamily 2, group F, member 1 |

| Pdcd4 | 1.00 | 0.14 | rc_AI172247_at | Programmed cell death 4 |

| Pdgfra | 1.10 | 0.28 | rc_AI232379_at | Platelet derived growth factor receptor, α polypeptide |

| Pla2g2a | 3.60 | 0.00 | X51529_at | Phospholipase A2, group IIA (platelets, synovial fluid) |

| Ptn | 2.10 | 0.57 | rc_AI102795_at | Pleiotrophin |

| Scg3 | 2.70 | 0.85 | U02983 | Secretogranin III |

| Serping1 | 0.85 | 0.21 | rc_AA800318_at | Serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade G, member 1 |

| Smad7 | 5.35 | 1.20 | AF042499_at | MAD homolog 7 (Drosophila) |

| Sod3 | 1.05 | 0.07 | Z24721_at | superoxide dismutase 3, extracellular |

| Zfp423 | 1.85 | 1.47 | U92564_at/U92564_g_at | Zinc finger protein 423 |

In general, many known mediators of TGF-β signaling were differentially expressed in AdSmad7 infected HSCs, confirming a direct link of Smad7 effects to TGF-β signalling (Table 2). ECM proteins like Col1a1 and Fn1 which are induced during HSC activation and fibrogenesis were negatively regulated upon Smad7 overexpression. Further profibrogenic cytokines like CXCL10 and HGF were upregulated. In addition, Cyp proteins like Cyp1b1, Cyp2E1 and Cyp4B1, Id proteins 1, 2, and 3, as well as PDGFR A were identified as Smad7 dependent in activated HSCs. Unexpectedly, several genes involved in glucose metabolism, so far annotated as predominantly associated with hepatocytes were influenced by Smad7 overexpression in HSCs.

As expected, Smad7 led to an opposite regulation of a number of recently systematically identified genes induced during HSC activation[14]. Table 3 contains a complete list of proteins identified to be regulated in both studies. In total, 37 genes of our study overlapped with the array results reported by[14]. Twenty-two of those (60%), e.g. HK2, were induced during activation[14] and decreased by Smad7 (this study) and therefore probably represent profibrogenic TGF-β target genes. There were also a few genes strongly upregulated by Smad7, which were downregulated during in vivo HSC activation, e.g. BMP2. Some of the proteins found to be differently regulated by activation vs Smad7 overexpression are already known to be TGF-β target genes and related to fibrogenesis, i.e. BMP2, Cnn1, Col1a1, Ddah1, Fn1, Lox, Pdgfra, Slc2a1, Slc16a3, and VEGF. Others might represent yet unidentified target genes of profibrogenic TGF-β signaling and/or new markers of HSC activation. Their specific influence on HSC transdifferentiation in vivo needs to be carefully investigated in future as they display potential antifibrotic target genes. In some cases De Minicis et al[14] reported opposite effects in regards to regulation of gene expression in “culture activated” cells compared to “in vivo activated” cells. This leaves a final evaluation of Smad7 influence on the regulation of these genes in HSC activation processes open.

| Gene symbol | Smad7 overexpressing HSCs | In vivo activated untransformed HSCs |

| Acta2 | ↓ | ↑ |

| BMP21 | ↑ | ↓ |

| Cnn1 | ↓ | ↑ |

| Col1a1 | ↓ | ↑ |

| Col3a1 | ↑ | ↑ |

| Cryab | ↓ | ↓ |

| Cyp1b1 | ↓ | ↑ |

| Ddah1 | ↓ | ↑ |

| Ednrb | ↑ | ↑2 |

| Eno2 | ↓ | ↓ |

| Ephx1 | ↑ | ↑2 |

| Fn1 | ↓ | ↑ |

| Gabbr1 | ↓ | ↓ |

| Hgf | ↑ | ↑2 |

| Hk21 | ↓ | ↑ |

| Hsd11b1 | ↑ | ↑2 |

| Id1 | ↓ | ↓ |

| Igfbp3 | ↑ | ↑2 |

| Kif4 | ↑ | ↑ |

| Lox | ↓ | ↑ |

| Lpl | ↓ | ↑2 |

| Lum | ↓ | ↑ |

| Ncam1 | ↓ | ↑ |

| P4ha1 | ↓ | ↑ |

| Pdgfra | ↑ | ↓ |

| Pfkp | ↓ | ↑ |

| Plod2 | ↓ | ↑ |

| Rasl11b | ↓ | ↑ |

| Serping1 | ↑ | ↑ |

| Slc16a3 | ↓ | ↑ |

| Slc2a1 | ↓ | ↑ |

| Sod3 | ↑ | ↑ |

| Tmepai_predicted | ↓ | ↓2 |

| Tnc | ↓ | ↓2 |

| Tnnt2 | ↓ | ↑ |

| VEGFa1 | ↓ | ↑ (VEGFc)1 |

| Wfdc1 | ↓ | ↑2 |

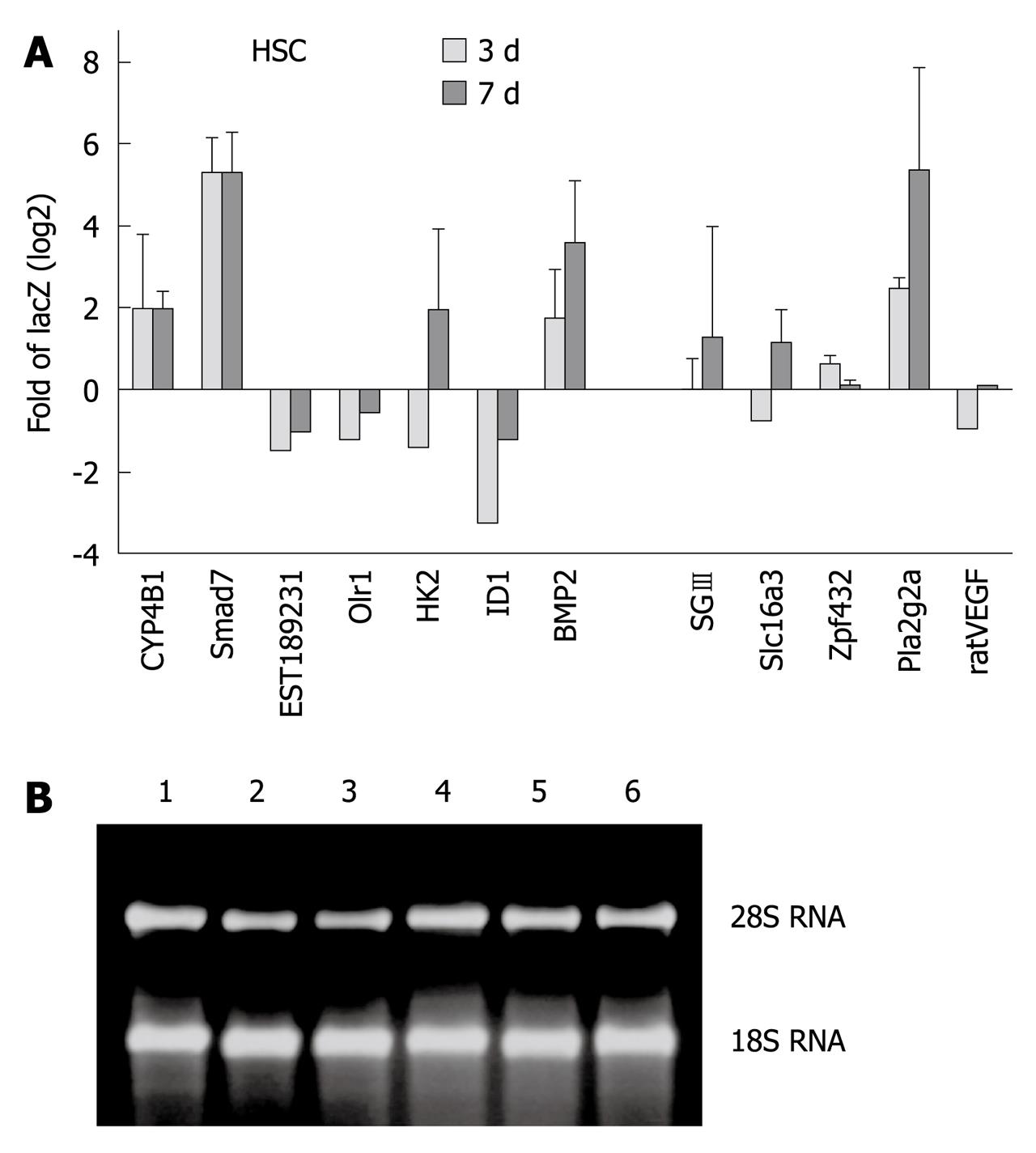

To validate our microarray results, we selected 12 genes from array data identified as highly regulated in dependency to Smad7 for RT-qPCR analysis. Transdifferentiating (3 d in culture) and fully activated (7 d in culture) HSCs were investigated. TGF-β RI mRNA expression is not modulated during transdifferentiation[15,16] and was used as the expression reference. A synopsis of Smad7 associated modulation of gene expression, given in Figure 4 as log2 fold of LacZ, generally supports the array results. We confirmed upregulation of Cyp4B1, BMP2, SGIII, Zfp423, Pla2g2a and downregulation of EST189231, Olr1 and Id1 (Table 4) independent of time during the transdifferentiation process.

| Gene | Probe set ID | Array | RT-PCR analysis |

| Cyp4B1 | M29853_at | Up | Up |

| Smad7 | AF042499_at | Up | Up |

| BMP2 | L02678_at/rc_AA997410_s_at | Up | Up |

| SGIII | U02983_at | Up | Up |

| Zfp423 | U92564_at/U92564_g_at | Up | Up |

| Pla2g2a | x51529_at | Up | Up |

| EST189231 | AA799734_at | Down | Down |

| Olr1 | AB005900_at/ AB018104cds_s_at/ rc_AI071531_s_at | Down | Down |

| ID1 | L23148_g_at | Down | Down |

| HK2 | D26393exon_s_at | Down | 3 d down/7 d up |

| Slc16a3 | U87627_at | Down | 3 d down/7 d up |

| VEGFa/ratVEGF.1 in RT-PCR | L20913_s_at/M32167_g_at | Down | 3 d down/7 d up |

Interestingly, when comparing 3 d- with 7 d-HSCs, opposite effects of Smad7 were found for HK2 (0.38-fold in 3 d-, 3.85-fold in 7 d-HSCs), Slc16a3 (0.59-fold in 3 d, 2.25-fold in 7 d-HSCs) and VEGF.1 (0.51-fold in 3 d-, 1.07-fold in 7 d-HSCs), underlining temporal differences and modulation of the TGF-β signal during HSC activation[15].

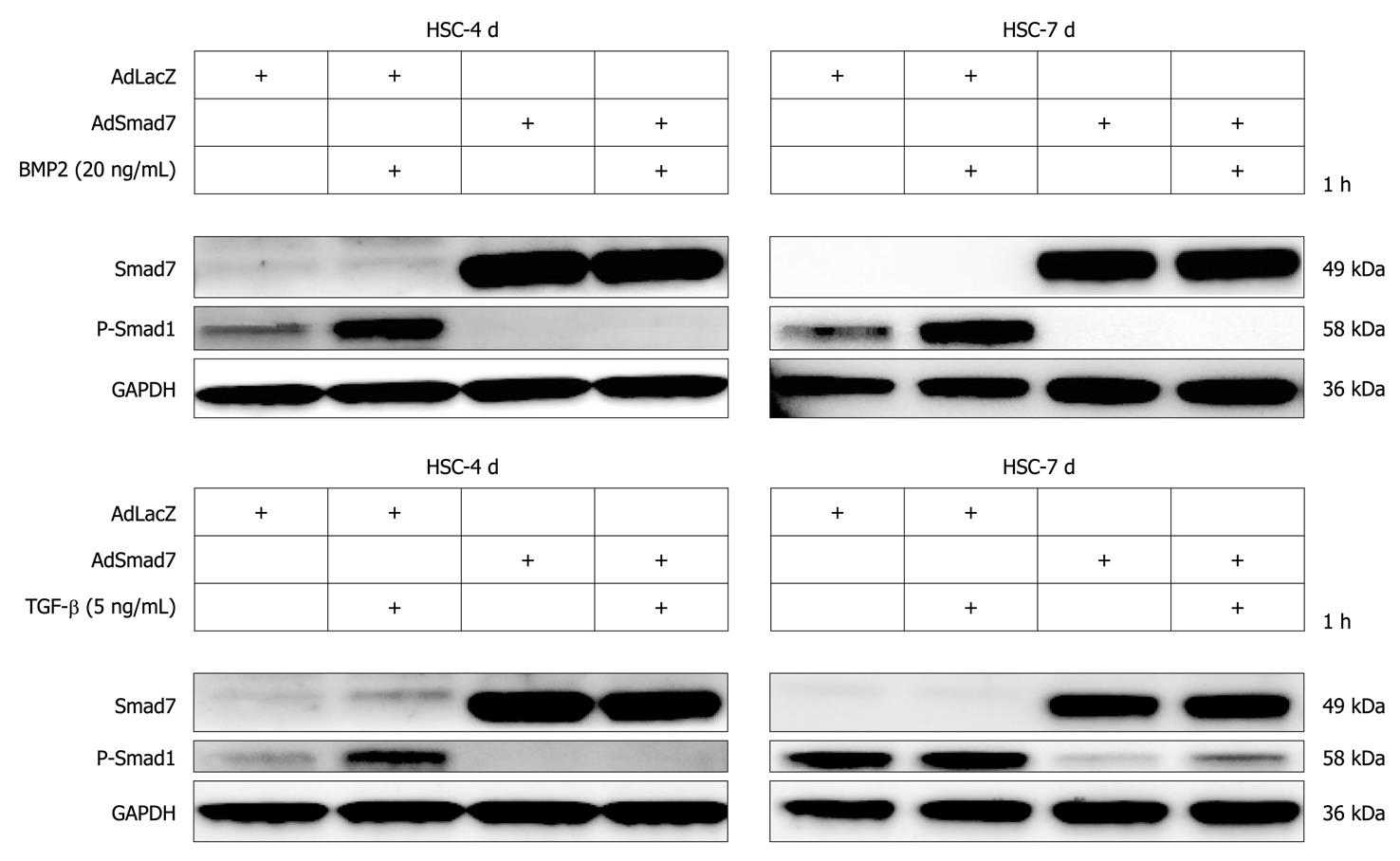

BMP2 was strongly upregulated in Smad7 expressing HSCs (Table 2, Figure 4A and B). Here, we further demonstrate that nevertheless Smad7 blunted BMP2 and TGF-β dependent signalling via Smad1 upon AdSmad7 infection in transdifferentiating (4 d in culture) rat HSCs (Figure 5) and infected CFSC (data not shown). Fully activated (7 d in culture) HSCs, which are insensitive to TGF-β, remain responsive to BMP2 mediated Smad1 phosphorylation, show the same tendency when stimulated with BMP2.

Using the Affymetrix Microarray approach, we systematically analyzed the effects of Smad7 overexpression during HSC transdifferentaition. About 100 genes were identified to be regulated upon Smad7 overexpression. For obvious reasons, only some of the regulated genes can be discussed below in detail. Nevertheless, all gene expression changes found constitute potential starting points for future research projects to unravel the process of liver fibrogenesis.

Pla2g2a and Cyp4B1 were strongly upregulated after Smad7 overexpression in HSCs. Pla2g2a participates in lipid metabolism/catabolism and was previously described as a tumor repressor in different cancer models, i.e. intestinal tumorigenesis, neuroblastoma, melanoma and colon cancer cell lines[17,18]. VEGF and Glut1, both known to be upregulated in tumor cells[19,20] were Smad7 dependently downregulated in HSCs. These results suggest an influence of Smad7 on tumor development and progression which is a long debated issue considering its regulative impact on ambiguous TGF-β signaling in tumorigenesis.

Cytochrome P450s are haem-thiolate proteins involved in oxidative degradation of particularly environmental toxins and mutagens and play a role in electron transport reactions. Additionally, they are key players in alcohol induced oxidative stress in liver, causing hepatocyte necrosis, apoptosis and liver fibrosis[21]. During steatosis, lipid peroxidation by Cyp2E1 is associated with inflammation and HSC activation including increased TGF-β production, possibly through up-regulation of KLF6[22]. Members of the Cyp P450 family are also upregulated during HSC activation[14].

Interestingly, overexpression of Smad7 increased the expression of some members of the Cytochrome P450 system through HSC activation, i.e. Cyp4B1 which is important in the metabolism of drugs, cholesterol, steroids and lipids, and Cyp2E1, while others are downregulated upon Smad7 overexpression, e.g. Cyp1B1. These ambiguous effects probably reflect the complex control of oxidative metabolism in the cell.

Hk2 is a hexokinase, one of the best known enzymes of glycolysis, and is involved in cell cycle progression. According to the results of the microarray analysis it represents the most downregulated gene in AdSmad7 infected HSCs. One feature of activated HSCs is the ability to proliferate. TGF-β antagonizes proliferation in quiescent HSCs, whereas it has a growth promoting effect in transdifferentiated MFBs. Thus, Hk2 might be induced by TGF-β in HSCs during activation, subsequently stimulating HSC proliferation and thus providing at least part of the growth stimulatory effect of TGF-β. Although physiological effects of glucose metabolism in the liver are traditionally associated to hepatocytes and provide a direct link to fibrogenesis via hyperglycemia and insulin resistance[23-25], one could speculate that activated HSCs need more energy and thus, glycolysis is upregulated TGF-β dependently in this cell type. In line, HSCs become sensitive to glucose signaling during activation, high glucose concentrations stimulate ROS production through PKC-dependent activation of NADPH oxidase and induce MAP kinase phosphorylation subsequent to proliferation and type I collagen production in this cell type[26] suggesting a crucial role of HSC-sugar metabolism in fibrogenesis.

Upregulation of Hk2 during activation of HSCs further suggests that glycolysis induction and increased levels of involved proteins may occur by other means than elevated blood glucose levels ([14], our study). This in turn indicates a direct connection between fibrosis and enhanced glycolysis independent of inducing external stimuli of either process.

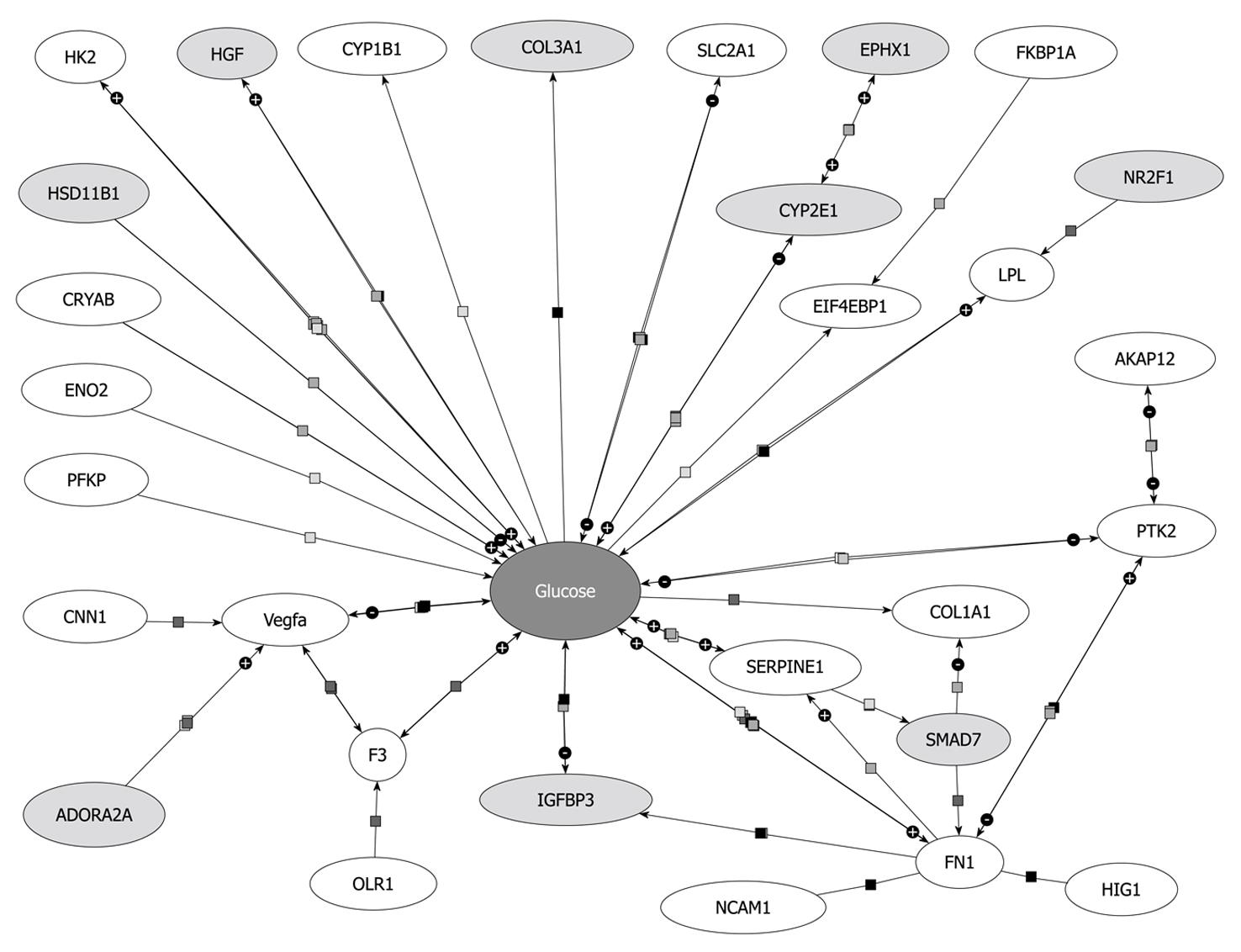

Beside Hk2 regulation, other genes encoding enzymes of glycolysis (Eno2, PFKP) or related to glucose metabolism were downregulated Smad7 dependently, e.g. VEGFa, PAI-1 (Serpine1), F3, Slc2a1 (Glut1), FN1, EIF4ebp1 and PTK2 (Figure 6). A list of all references proving the relation of these genes to glucose metabolism will be provided to interested readers on request.

Glut1 is a glucose transporter protein which becomes upregulated in activated HSCs or upon HSC activation[14]. Since Smad7 decreases Glut1 expression levels and other proteins involved in glycolysis, TGF-β seems to enhance glucose metabolism and energy supply during HSC activation thus enabling the cells to proliferate and transdifferentiate towards activated myofibroblasts.

In contrast, decreased numbers of Glut1 molecules are reported in hepatocytes subjected to chronic alcohol consumption[27] resulting in a reduced availability of glucose for glycolysis in hepatocytes. The resulting energy deficiency has been shown to impair this cell type’s ability to perform critical functions and to contribute therefore to cell death and alcoholic liver disease.

In line with our results, relations between glucose metabolism and fibroproliferative processes were identified in other organs. For example in human kidney[28,29] exposure of proximal tubule cells and cortical fibroblasts to high extracellular glucose concentrations results directly in altered cell growth and collagen synthesis.

IGFBP3 and Cyp2E1, known to participate in glucose metabolism were upregulated in AdSmad7 infected HSCs, indicating that they might be under negative control through TGF-β. However, upregulation of IGFBP3 in our study could be simply due to “culture” but not “in vivo activation” of HSCs (for term definition compare[14]) instead of being mechanistically important. Interestingly, Smad7 even seems to enhance the upregulation of IGFBP3, which already occurs upon HSC activation. If there is any pathologic relevance of this finding, it suggests a mechanism of regulation independent of canonical TGF-β/Smad7 signaling in HSC activation.

VEGFs are growth factors involved in angiogenesis, vasculogenesis and endothelial cell growth, promotion of cell migration, apoptosis inhibition and induction of blood vessel permeabilization. De Minicis et al[14] showed VEGFc to be upregulated[14], while in the present report VEGFa was downregulated after Smad7 overexpression in activated HSCs, indicating its induction as a response to profibrogenic TGF-β signaling. Previous investigation of hypoxia in a stellate cell line demonstrates upregulation of VEGF expression[30]. Hypoxia leads to cell dysfunction or death and occurs during liver damage and inflammation. HIF1, considered to be the major regulator of about 100 genes including VEGF and PAI-1, is also upregulated in that study. In contrast HIF1 did not display an altered expression in our study indicating that HIF1 expression in HSCs is TGF-β independent and that another TGF-β dependent route exists to induce PAI-1 (serpine1) and VEGFa expression.

Expression of several proteins linked to cell adhesion, i.e. Olr1, Ncam1, Fn1 and Tnc was decreased after Smad7 overexpression in HSCs. Accordingly, Ncam1 and Fn1 were upregulated in activated HSCs[14]. Although for Olr1 no information about the regulation in activated HSCs is available so far, we assume from our results that Smad7 antagonizes cell adhesion features of activated HSCs. This suggests that profibrogenic TGF-β signaling improves cell adhesion for transdifferentiating HSCs. Nevertheless it should be noted that downregulation of Tnc in activated HSCs is supported by Smad7.

Generally, TGF-β signals via Smad2 and Smad3 but also induces the second canonical pathway via ALK1/Smad1/5/8. BMP2, another member of the TGF-β family, solely signals via Smads1/5/8 utilizing ALK3 and ALK6[12]. Here we show that (1) BMP2 was strongly upregulated in Smad7 expressing HSCs (Table 2, Figure 4A and B); and (2) Smad7 potently inhibited BMP2 dependent and TGF-β dependent Smad1 phosphorylation. Even in fully activated HSCs which are not responsive to TGF-β concerning Smad1 phosphorylation, BMP2 dependent Smad1 phosphorylation was abolished (Figure 5).

These results indicate a tight crosstalk between TGF-β and BMP signaling pathways in HSCs. It seems that HSCs try to keep up a functional Smad1 signaling upon blocking TGF-β pathways with Smad7. Accordingly, BMP2 is capable of inducing Smad1 signaling in fully activated 7 d-HSCs which are no longer responsive to TGF-β stimulation. Thus BMP2 expression might be induced to overcome a lack of TGF-β/Smad1 signaling upon Smad7 expression or HSC activation using a corresponding autocrine loop. Although our in vitro experiments demonstrate that Smad7 is able to inhibit BMP2/Smad1 signaling effectively, Smad7 dependent induction of BMP2 expression in HSCs in vivo might be strong enough to sustain an active Smad1/5/8 signaling pathway. Further experiments could delineate whether BMP2 expression is directly induced by the recently described DNA binding activity of Smad7[31], if a running TGF-β signaling pathway has a negative regulatory role toward the BMP2 promoter or if other mechanisms are responsible for BMP2 induction in Smad7 overexpressing HSCs.

In summary we conclude that genes regulated contrarily during HSC activation[14] vs ectopic Smad7 expression (this study) most probably represent critical profibrogenic components. As Smad7 is able to blunt HSC transdifferentiation in vitro and in vivo[7] we assume glucose metabolism and the crosstalk between the TGF-β and the BMP2 pathways are critical components of HSC activation.

In general our study underlines the potential of top down systemic approaches to delineate effects of cell signaling regulation and opens the opportunity to find targets for drug development.

Activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) as a consequence of liver damage includes proliferation and extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition and represents a major step in fibrogenesis. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β is a master contributor and its signaling pathway is modulated during the HSC activation process, whereby its cytostatic action is lost and ECM producing effects become predominant. Smad7 is a powerful antagonist of TGF-β. Expression of Smad7 is transiently induced by the canonical TGF-β/R-Smad signaling cascade, thereby providing a negative feedback loop to regulate TGF-β signals. Smad7 is able to inhibit HSC transdifferentiation and attenuate the extent of fibrosis, suggesting Smad7 is a promising antifibrotic compound.

The findings offer important new information about the process of HSC transdifferentiation and fibrogenesis as well as cell biology of signal transduction in the liver. Moreover, providing a list of genes previously not known as participants in HSC activation and fibrogenesis, members of the field may use these data as starting points to get new insight into mechanisms of HSC (patho)physiology. Thus, it will definitely be of interest to the scientific community, especially in the field of hepatology and gastroenterology.

In the present report, the authors systematically investigated transcriptional effects of Smad7 overexpression in cultured HSCs by microarray analysis. Using this powerful top down approach, the authors identified 100 target genes to be significantly regulated by Smad7 overexpression. These represent potential targets for delineating mechanisms of HSC activation and to set up therapeutic approaches. The results imply a crosstalk between TGF-β and BMP2 signaling pathways in HSCs and for the first time a significant involvement of glucose metabolism in the HSC transdifferentiation processes.

The results are of special interest for future attempts to understand the process of stellate cell activation and to set up TGF-β and/or Smad7 directed treatment approaches in chronic liver diseases, especially as they reflect the most powerful negative regulatory process of TGF-β signaling.

Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP): BMPs are multi-functional growth factors belonging to the TGF-β superfamily. BMPs were originally discovered by their ability to induce the formation of bone and cartilage, but are now considered to constitute a group of pivotal morphogenetic signals, orchestrating tissue architecture throughout the body. BMP signals are mediated by type I and II BMP receptors and their downstream molecules Smad1, 5 and 8. Microarray: A method for profiling gene and protein expression in cells and tissues. A microarray consists of different nucleic acid/protein probes that are chemically attached to a substrate, which can be a microchip, a glass slide or a microsphere-sized bead. Hybridization of test samples to these probes can be measured by different means.

This is a potentially interesting study aimed at clarifying Smad7-regulated gene expression during the transdifferentiation of hepatic stellate cells, a major profibrogenic cell type in the liver. Overall, the study is well-performed and the manuscript is well-written.

| 1. | Arthur MJ. Fibrogenesis II. Metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in liver fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;279:G245-G249. |

| 2. | Bataller R, Brenner DA. Liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:209-218. |

| 3. | Weng H, Mertens PR, Gressner AM, Dooley S. IFN-gamma abrogates profibrogenic TGF-beta signaling in liver by targeting expression of inhibitory and receptor Smads. J Hepatol. 2007;46:295-303. |

| 4. | Weng HL, Wang BE, Jia JD, Wu WF, Xian JZ, Mertens PR, Cai WM, Dooley S. Effect of interferon-gamma on hepatic fibrosis in chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a randomized controlled study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:819-828. |

| 5. | Purps O, Lahme B, Gressner AM, Meindl-Beinker NM, Dooley S. Loss of TGF-beta dependent growth control during HSC transdifferentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;353:841-847. |

| 6. | Dooley S, Said HM, Gressner AM, Floege J, En-Nia A, Mertens PR. Y-box protein-1 is the crucial mediator of antifibrotic interferon-gamma effects. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:1784-1795. |

| 7. | Dooley S, Hamzavi J, Breitkopf K, Wiercinska E, Said HM, Lorenzen J, Ten Dijke P, Gressner AM. Smad7 prevents activation of hepatic stellate cells and liver fibrosis in rats. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:178-191. |

| 8. | Stopa M, Anhuf D, Terstegen L, Gatsios P, Gressner AM, Dooley S. Participation of Smad2, Smad3, and Smad4 in transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta)-induced activation of Smad7. THE TGF-beta response element of the promoter requires functional Smad binding element and E-box sequences for transcriptional regulation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29308-29317. |

| 9. | Knook DL, DeLeeuw AM. Isolation and characterization of fat storing cells from the rat liver. Sinusoidal liver cells. Rijswijk: Elsevier Biomedical Press 1982; 45-52. |

| 10. | Schäfer S, Zerbe O, Gressner AM. The synthesis of proteoglycans in fat-storing cells of rat liver. Hepatology. 1987;7:680-687. |

| 11. | Wickert L, Steinkrüger S, Abiaka M, Bolkenius U, Purps O, Schnabel C, Gressner AM. Quantitative monitoring of the mRNA expression pattern of the TGF-beta-isoforms (beta 1, beta 2, beta 3) during transdifferentiation of hepatic stellate cells using a newly developed real-time SYBR Green PCR. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;295:330-335. |

| 12. | Wiercinska E, Wickert L, Denecke B, Said HM, Hamzavi J, Gressner AM, Thorikay M, ten Dijke P, Mertens PR, Breitkopf K. Id1 is a critical mediator in TGF-beta-induced transdifferentiation of rat hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2006;43:1032-1041. |

| 13. | Zeeberg BR, Feng W, Wang G, Wang MD, Fojo AT, Sunshine M, Narasimhan S, Kane DW, Reinhold WC, Lababidi S. GoMiner: a resource for biological interpretation of genomic and proteomic data. Genome Biol. 2003;4:R28. |

| 14. | De Minicis S, Seki E, Uchinami H, Kluwe J, Zhang Y, Brenner DA, Schwabe RF. Gene expression profiles during hepatic stellate cell activation in culture and in vivo. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1937-1946. |

| 15. | Dooley S, Delvoux B, Lahme B, Mangasser-Stephan K, Gressner AM. Modulation of transforming growth factor beta response and signaling during transdifferentiation of rat hepatic stellate cells to myofibroblasts. Hepatology. 2000;31:1094-1106. |

| 16. | Wickert L, Abiaka M, Bolkenius U, Gressner AM. Corticosteroids stimulate selectively transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta receptor type III expression in transdifferentiating hepatic stellate cells. J Hepatol. 2004;40:69-76. |

| 17. | Cormier RT, Hong KH, Halberg RB, Hawkins TL, Richardson P, Mulherkar R, Dove WF, Lander ES. Secretory phospholipase Pla2g2a confers resistance to intestinal tumorigenesis. Nat Genet. 1997;17:88-91. |

| 18. | Haluska FG, Thiele C, Goldstein A, Tsao H, Benoit EP, Housman D. Lack of phospholipase A2 mutations in neuroblastoma, melanoma and colon-cancer cell lines. Int J Cancer. 1997;72:337-339. |

| 19. | Vaupel P, Mayer A. Hypoxia in cancer: significance and impact on clinical outcome. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26:225-239. |

| 20. | Suganuma N, Segade F, Matsuzu K, Bowden DW. Differential expression of facilitative glucose transporters in normal and tumour kidney tissues. BJU Int. 2007;99:1143-1149. |

| 21. | Albano E. Alcohol, oxidative stress and free radical damage. Proc Nutr Soc. 2006;65:278-290. |

| 22. | Stärkel P, Sempoux C, Leclercq I, Herin M, Deby C, Desager JP, Horsmans Y. Oxidative stress, KLF6 and transforming growth factor-beta up-regulation differentiate non-alcoholic steatohepatitis progressing to fibrosis from uncomplicated steatosis in rats. J Hepatol. 2003;39:538-546. |

| 23. | Canbay A, Gieseler RK, Gores GJ, Gerken G. The relationship between apoptosis and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: an evolutionary cornerstone turned pathogenic. Z Gastroenterol. 2005;43:211-217. |

| 24. | Parekh S, Anania FA. Abnormal lipid and glucose metabolism in obesity: implications for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2191-2207. |

| 25. | Kmieć Z. Cooperation of liver cells in health and disease. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 2001;161:III-XIII, 1-151. |

| 26. | Sugimoto R, Enjoji M, Kohjima M, Tsuruta S, Fukushima M, Iwao M, Sonta T, Kotoh K, Inoguchi T, Nakamuta M. High glucose stimulates hepatic stellate cells to proliferate and to produce collagen through free radical production and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase. Liver Int. 2005;25:1018-1026. |

| 27. | Van Horn CG, Ivester P, Cunningham CC. Chronic ethanol consumption and liver glycogen synthesis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;392:145-152. |

| 28. | Jones SC, Saunders HJ, Pollock CA. High glucose increases growth and collagen synthesis in cultured human tubulointerstitial cells. Diabet Med. 1999;16:932-938. |

| 29. | Gilbert RE, Cooper ME. The tubulointerstitium in progressive diabetic kidney disease: more than an aftermath of glomerular injury? Kidney Int. 1999;56:1627-1637. |

| 30. | Shi YF, Fong CC, Zhang Q, Cheung PY, Tzang CH, Wu RS, Yang M. Hypoxia induces the activation of human hepatic stellate cells LX-2 through TGF-beta signaling pathway. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:203-210. |

| 31. | Shi X, Chen F, Yu J, Xu Y, Zhang S, Chen YG, Fang X. Study of interaction between Smad7 and DNA by single-molecule force spectroscopy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377:1284-1287. |

Peer reviewers: Mark D Gorrell, PhD, Professor, Centenary Institute of Cancer Medicine and Cell Biology, Locked bag No. 6, Newtown, NSW 2042, Australia; Atsushi Masamune, MD, PhD, Division of Gastroenterology, Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine, 1-1 Seiryo-machi, Aoba-ku, Sendai 980-8574, Japan

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Zheng XM