Published online Jan 28, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i4.513

Revised: December 9, 2009

Accepted: December 16, 2009

Published online: January 28, 2010

AIM: To introduce and evaluate the new method used in treatment of pancreatic and peripancreatic infections secondary to severe acute pancreatitis (SAP).

METHODS: A total of 42 SAP patients initially underwent ultrasound-guided percutaneous puncture and catheterization. An 8-Fr drainage catheter was used to drain the infected peripancreatic necrotic foci for 3-5 d. The sinus tract of the drainage catheter was expanded gradually with a skin expander, and the 8-Fr drainage catheter was replaced with a 22-Fr drainage tube after 7-10 d. Choledochoscope-guided debridement was performed repeatedly until the infected peripancreatic tissue was effectively removed through the drainage sinus tract.

RESULTS: Among the 42 patients, the infected peripancreatic tissue or abscess was completely removed from 38 patients and elective cyst-jejunum anastomosis was performed in 4 patients due to formation of pancreatic pseudocysts. No death and complication occurred during the procedure.

CONCLUSION: Percutaneous catheter drainage in combination with choledochoscope-guided debridement is a simple, safe and reliable treatment procedure for peripancreatic infections secondary to SAP.

- Citation: Tang LJ, Wang T, Cui JF, Zhang BY, Li S, Li DX, Zhou S. Percutaneous catheter drainage in combination with choledochoscope-guided debridement in treatment of peripancreatic infection. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(4): 513-517

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i4/513.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i4.513

Severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) is an extremely dangerous and refractory disease characterized by complicated pathogenesis and high mortality[1]. Secondary peripancreatic infection is a severe complication of SAP, which is one of the main causes for death of SAP patients[2]. Clinically, peripancreatic infection can be divided into infected effusion containing rich pancreatin around the pancreas occurring in early SAP, and infected pancreatic and peripancreatic necrosis, peripancreatic abscess usually observed during the course of SAP progress. In addition to the clinical signs and symptoms of bacterial infection, SAP patients have a large amount of necrotic peripancreatic tissue and fluid which can be found by imaging analysis, computed tomography (CT) or ultrasonography[3,4].

Open surgical debridement is a traditional procedure for SAP patients with infected peripancreatic foci[5-7]. However, it should not be performed in early SAP[2,7-9]. Since the infected peripancreatic foci in early SAP are not well encapsulated by fibrous connective tissue and no visible distinct boundary can be observed between infected necrotic tissue and living pancreas or peripancreatic tissue, it is difficult to completely remove the necrotic tissues, with a re-operation rate of 18%-68%[10]. In addition, the function of vital organs, including lung and kidney, is often insufficient in early SAP patients, and is further deteriorated by open-abdominal surgery, leading to multiple vital organ failure and death. Therefore, it is generally agreed that surgical debridement should be delayed until the infected peripancreatic foci are well demarcated[2,7].

If debridement could not be performed in early SAP, the infected peripancreatic necrotic tissue and effusion would become the source of infection in other organs. In addition, peripancreatic effusion containing enzyme-enriched pancreatic juice can further corrode the peripancreatic tissue, leading to more severe peripancreatic necrosis. Furthermore, retroperitoneal necrotic tissue and effusion may stimulate celiac nerves that can induce enteroparalysis and exacerbate abdominal distension, leading to respiratory and cardiac failure in severe cases. Thus, it is necessary to remove the infected peripancreatic tissue and effusion promptly and effectively.

In this retrospective study, early SAP patients were treated with ultrasound-guided puncture and catheter drainage in combination with early debridement under choledochoscope.

A total of 42 patients (25 males and 17 females), at the age of 24-67 years, were diagnosed as SAP according to the “Atlanta classification of acute pancreatitis” in 2001-July 2008 in our hospital[11]. The disease was due to alcohol drinking, stones in the common bile duct, and unknown etiology in 9, 8, and 25 patients, respectively. Physical examination revealed abdominal tenderness, rebound pain, distention, and hypoactive or absent bowel sounds, one or more organ failure, pulmonary insufficiency, renal failure, systemic complications, low calcium, presence of infected necrotic tissue and fluid surrounding the pancreas. Patients received relevant treatment to maintain their vital organ functions. However, infected peripancreatic foci still remained after treatment. Once the infected foci were localized, patients should be immediately treated with ultrasound-guided percutaneous puncture and catheter drainage.

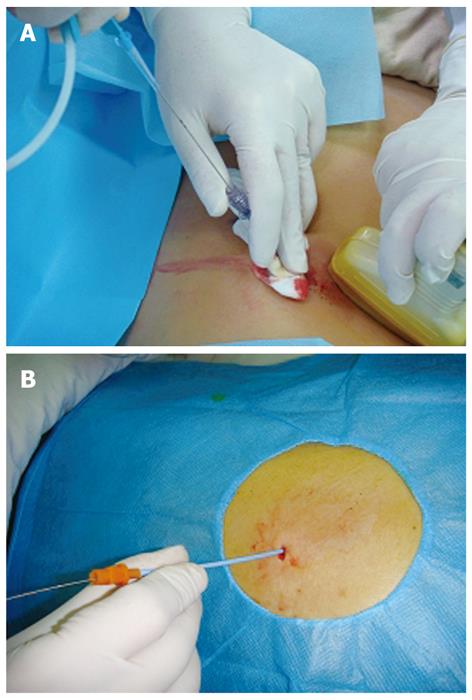

Patients underwent abdominal ultrasound examination at a supine position to determine the safe site and direction of percutaneous puncture. The selected puncture site was close to the focus. Under the guidance of ultrasound, an 18-G puncture needle (Promex Company, USA) was inserted into the focus through the abdominal wall and the needle core was then pulled out. Pus and necrotic tissue fragments were drawn out from the focus. A guidewire was then placed in the deepest location of the focus via the puncture needle lumen under ultrasonic monitoring (Figure 1A). After the puncture needle was slowly removed, an 8-Fr skin expander (Cook Corporation, USA) was inserted along with the guidewire. Once the abdominal wall layers were properly expanded, the skin expander was removed and an 8-Fr drainage catheter (Hakko International Trading Co., Ltd.) was immediately inserted into the focus along with the guidewire (Figure 1B). Finally, the guidewire was pulled out with the drainage catheter fixed on the abdominal wall.

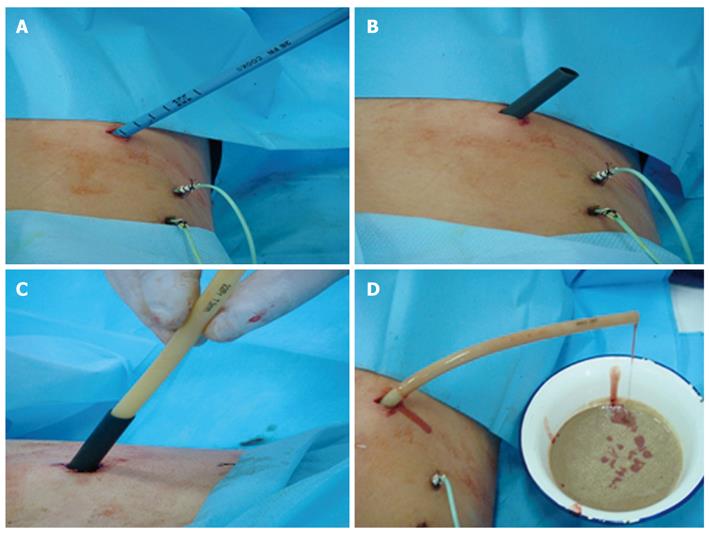

The infected peripancreatic fluid was drained through the 8-Fr drainage catheter for 3-5 d, and then the drainage catheter was replaced with a large drainage tube. First, a guidewire was inserted into the focus through the lumen of the 8-Fr drainage catheter which was then removed. In order to apply a larger tube, patients were given local anesthesia with 0.5% procaine and a 1 cm-deep small incision was made through the skin and subcutis, and then the 8-Fr skin expander was inserted along with the guidewire to expand the sinus tract made initially by the drainage catheter. Second, the 8-Fr skin expander was pulled out, and 12-, 16-, 20-, and 24-Fr skin expanders with a diameter of 8 mm were inserted to gradually expand the sinus tract (Figure 2A). A sheath matching the 24-Fr skin expander was inserted and left in the focus (Figure 2B), and the expander was then removed. Finally, a 22-Fr drainage tube was inserted into the focus through the sheath lumen of the 24-Fr skin expander (Figure 2C and D).

A sinus tract around the drainage tube was firmly formed 7 d after drainage with the larger drainage tube. Meanwhile, the peripancreatic focus was also encapsulated with fibrous connective tissue, and then debridement was performed under choledochoscope (Pentax Co. Japan). The large drainage tube was removed, and a choledochoscope was slowly inserted into the peripancreatic focus through the sinus tract of the drainage tube (Figure 3A and B). Sterile saline was rapidly injected into the focus through the water inlet of choledochoscope. After a certain amount of saline was injected into the focus, the choledochoscope was removed with pus and necrotic tissue fragments flushed out. During the procedure, bigger pieces of necrotic tissue were removed with biopsy forceps under choledochoscope. The necrotic tissue fragments were irrigated until the effluent became clear (Figure 3C). The focus was finally flushed with 0.5% metronidazole. A drainage tube was placed into the focus through the original sinus tract and left there for next debridement.

The time from the onset of pancreatitis to drainage was 4-11 d (mean 5.3 d). The number of 8-Fr drainage catheters used for external drainage was 1-5 (mean 2.2 catheters) depending on the number and locations of infected peripancreatic foci. Before the sinus tract was expanded, the external drainage was maintained for 3-5 d (mean 3.6 d). A large 22-Fr drainage tube was used for 7-10 d (mean 8.2 d).

Based on the amount of infected peripancreatic necrotic tissue and pus, the presence of systematic infection symptoms, each of the 42 patients underwent 5-14 times of choledochoscope-guided debridement (mean 8.5 times) at an interval of 2-7 d (mean 4.5 d).

After the infected peripancreatic foci were removed, the infection of patients was well controlled with decreased body temperature and normal blood leukocyte count, and the overall conditions of patients were significantly improved. CT or ultrasonic scanning showed that their infected peripancreatic necrotic tissue and fluid were significantly diminished or completely disappeared. Thirty eight out of the 42 patients were discharged from the hospital with a cure rate of 90.5%. The remaining 4 patients underwent elective cyst-jejunum anastomosis due to formation of pancreatic pseudocysts. The hospital stay time of the patients was 1-3 mo (mean 1.5 mo) depending on the severity of SAP. No complications such as hemorrhage or intestinal leakage occurred.

Death of SAP patients may occur due to multiple organ dysfunction and severe peripancreatic infection secondary to SAP. In recent years, most SAP patients can survive after proper treatment. Since secondary peripancreatic infection may become the most refractory cause for death of SAP patients, its effective treatment is an urgent challenge for surgeons. In fact, peripancreatic effusion and infection have been existed in the early pathological process of SAP. As early as 1980s, the risk of early peripancreatic infection was recognized, and early surgical debridement in combination with postoperative drainage has become the effective procedure since then. However, it is difficult for the procedure to completely remove the infected peripancreatic necrosis tissue, and the procedure itself may result in multiple complications with high mortality. Therefore, it is generally recommended that surgical debridement should be delayed until the infected peripancreatic focus is localized and encapsulated. However, if the infected peripancreatic focus is not removed or drained, it can further exacerbate peripancreatic infection and SAP symptoms.

Some minimal invasive treatment modalities are available for pancreatic and peripancreatic infection, including CT-guided percutaneous catheter drainage[12,13], retroperitoneal debridement and drainage[14,15], and laparoscopic-assisted percutaneous drainage[16,17]. These procedures can resolve peripancreatic fluid collection and reduce peripancreatic infection-associated mortality. However, they are insufficient to treat peripancreatic infection secondary to SAP. Segal et al[15] used CT-guided percutaneous puncture and catheterization to drain the infected peripancreatic effusion and found that only slender drainage catheters can be placed in the infected focus and the infected effusion secondary to SAP is mixed with necrotic pancreatic and peripancreatic tissue fragments, which in turn block the slender drainage catheter and make it difficult to drain the infected effusion.

In the present study, an 8-Fr drainage catheter was placed into the focus under the guidance of ultrasound for a few days, and the sinus tract was expanded using a skin expander, and then a large drainage tube was used to drain the effusion. Since more and more necrotic tissue and pus are accumulated in the peripancreatic focus due to the pathological features of SAP itself, it is almost impossible to completely drain the infected necrotic tissue fragments with only one or several drainage tubes. Accordingly, debridement followed by postoperative drainage appears to be the only effective procedure. However, it causes additional traumas and postoperative complications, such as hemorrhage and intestinal leakage. Even though the infected focus is localized or well encapsulated, it is also difficult to completely remove the infected peripancreatic necrotic foci during an open-abdominal operation.

Choledochoscope is widely used in biliary surgery because of its easy manipulation and good flexibility. Flexible choledochoscope can reach various locations of the infected foci, thus guiding the flushing and debridement with minimal invasive intervention but no general anesthesia. In our study, choledochoscope was used to assist the debridement and flushing after the infected peripancreatic focus was drained with a large drainage tube for a few days when a fibrous wall was formed around the sinus tract. In this way, continuously generated necrotic tissue can be completely discarded. As a result, 38 out of the 42 SAP patients completely recovered without any complications with cure rate of 90.5% and no death occurred after treatment with the procedure, indicating that this procedure is safe, reliable and efficient to treat peripancreatic infection.

The following points should be addressed. First, in order to avoid damage to adjacent blood vessels and vital organs during puncture prior to catheterization, the puncture site should be carefully located under the guidance of ultrasound and the needle should be close to the focus. Second, the choledochoscope should not be inserted arbitrarily as it may prick the blood vessels in the focus leading to bleeding. Third, since smaller fragments of removable necrotic tissue in the focus can be cleaned by flushing with a large amount of sterile saline through the water inlet of choledochoscope, and larger removable necrotic tissue pieces can be gently removed with a biopsy forceps. However, adhered necrotic tissue pieces should not be fiercely removed with the forceps since they will gradually become loose during the pathological process of SAP and can be removed in the next debridement under choledochoscope.

In summary, peripancreatic infection secondary to SAP can be treated promptly and efficiently with ultrasound-guided puncture and percutaneous catheter drainage followed by multiple debridement under choledochoscope. This procedure, in particular, can be performed in early SAP. Since this procedure does not require general anesthesia and open the peritoneal cavity with minimal surgical traumas, it can be safely performed for critically ill patients or for those who are unfit to undergo conventional surgical debridement. Percutaneous catheter drainage combined with choledochoscope-guided debridement can serve as an alternative to surgical debridement. We believe that this procedure is a novel and effective approach to the treatment of peripancreatic infection secondary to SAP.

Peripancreatic infection is a severe complication of severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) with a high mortality. Surgical debridement is necessary to remove infected tissue but it should be delayed till the peripancreatic infected tissue is demarcated. However, the presence of infected peripancreatic tissue without prompt debridement can further deteriorate the clinic condition of SAP patients. Thus, removal of the infected peripancreatic tissue timely and effectively becomes an urgent challenge for treatment of SAP patients.

Peripancreatic infection is one of the main causes for death of SAP patients. Open surgical debridement is a traditional treatment for peripancreatic infection, but it is believed that open surgical debridement can not completely remove necrotic tissues and further lead to multiple vital organ failure and death. Thus, it is necessary to remove infected peripancreatic tissue and effusion with minimal invasive approaches promptly and effectively.

The results of this study have provided the evidence of successful treatment for early SAP patients using the ultrasound-guided puncture and catheter drainage combined with repeated debridement under choledochoscope, which can achieve satisfactory outcome.

The procedure introduced in this study can be used as an alternative to the conventional open-abdominal surgical or laparoscopic debridement in treatment of peripancreatic infection of early SAP patients.

The study is interesting and impressive. The authors revealed the effectiveness and safety of the new procedure they used. Although no control group was provided, the results can be accepted.

| 1. | Beger HG, Rau B, Mayer J, Pralle U. Natural course of acute pancreatitis. World J Surg. 1997;21:130-135. |

| 2. | Werner J, Hartwig W, Hackert T, Büchler MW. Surgery in the treatment of acute pancreatitis--open pancreatic necrosectomy. Scand J Surg. 2005;94:130-134. |

| 3. | Banks PA, Freeman ML. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2379-2400. |

| 4. | Balthazar EJ. Complications of acute pancreatitis: clinical and CT evaluation. Radiol Clin North Am. 2002;40:1211-1227. |

| 5. | Bouvet M, Moussa AR. Pancreatic abscess. Current surgical therapy. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby 2004; 476-480. |

| 6. | Werner J, Uhl W, Buchler MW. Acute pancreatitis. Current surgical therapy. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby 2004; 459-469. |

| 7. | Haney JC, Pappas TN. Necrotizing pancreatitis: diagnosis and management. Surg Clin North Am. 2007;87:1431-1446, ix. |

| 8. | Dionigi R, Rovera F, Dionigi G, Diurni M, Cuffari S. Infected pancreatic necrosis. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2006;7 Suppl 2:S49-S52. |

| 9. | Heinrich S, Schäfer M, Rousson V, Clavien PA. Evidence-based treatment of acute pancreatitis: a look at established paradigms. Ann Surg. 2006;243:154-168. |

| 10. | Beger HG, Rau BM. Severe acute pancreatitis: Clinical course and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5043-5051. |

| 11. | Bradley EL 3rd. A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis. Summary of the International Symposium on Acute Pancreatitis, Atlanta, Ga, September 11 through 13, 1992. Arch Surg. 1993;128:586-590. |

| 12. | Freeny PC, Lewis GP, Traverso LW, Ryan JA. Infected pancreatic fluid collections: percutaneous catheter drainage. Radiology. 1988;167:435-441. |

| 13. | Balthazar EJ, Freeny PC, vanSonnenberg E. Imaging and intervention in acute pancreatitis. Radiology. 1994;193:297-306. |

| 14. | Connor S, Ghaneh P, Raraty M, Sutton R, Rosso E, Garvey CJ, Hughes ML, Evans JC, Rowlands P, Neoptolemos JP. Minimally invasive retroperitoneal pancreatic necrosectomy. Dig Surg. 2003;20:270-277. |

| 15. | Segal D, Mortele KJ, Banks PA, Silverman SG. Acute necrotizing pancreatitis: role of CT-guided percutaneous catheter drainage. Abdom Imaging. 2007;32:351-361. |

| 16. | Gambiez LP, Denimal FA, Porte HL, Saudemont A, Chambon JP, Quandalle PA. Retroperitoneal approach and endoscopic management of peripancreatic necrosis collections. Arch Surg. 1998;133:66-72. |

| 17. | Horvath KD, Kao LS, Ali A, Wherry KL, Pellegrini CA, Sinanan MN. Laparoscopic assisted percutaneous drainage of infected pancreatic necrosis. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:677-682. |

Peer reviewer: Naoaki Sakata, MD, PhD, Division of Hepato-Biliary Pancreatic Surgery, Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine, 1-1 Seiryo-machi, Aoba-ku, Sendai, Miyagi 980-8574, Japan

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Ma WH