Published online Sep 14, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i34.4341

Revised: May 20, 2010

Accepted: May 27, 2010

Published online: September 14, 2010

AIM: To study the pathophysiological significance of gallbladder volume (GBV) and ejection fraction changes in gallstone patients.

METHODS: The fasting GBV of gallstone patients with acute cholecystitis (n = 99), chronic cholecystitis (n = 85) and non-gallstone disease (n = 240) were measured by preoperative computed tomography. Direct saline injection measurements of GBV after cholecystectomy were also performed. The fasting and postprandial GBV of 65 patients with gallstones and chronic cholecystitis and 53 healthy subjects who received health examinations were measured by abdominal ultrasonography. Proper adjustments were made after the correction factors were calculated by comparing the preoperative and postoperative measurements. Pathological correlations between gallbladder changes in patients with acute calculous cholecystitis and the stages defined by the Tokyo International Consensus Meeting in 2007 were made. Unpaired Student’s t tests were used. P < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

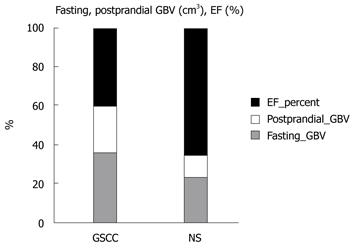

RESULTS: The fasting GBV was larger in late stage than in early/second stage acute cholecystitis gallbladders (84.66 ± 26.32 cm3, n = 12, vs 53.19 ± 33.80 cm3, n = 87, P = 0.002). The fasting volume/ejection fraction of gallbladders in chronic cholecystitis were larger/lower than those of normal subjects (28.77 ± 15.00 cm3vs 6.77 ± 15.75 cm3, P < 0.0001)/(34.6% ± 10.6%, n = 65, vs 53.3% ± 24.9%, n = 53, P < 0.0001).

CONCLUSION: GBV increases as acute cholecystitis progresses to gangrene and/or empyema. Gallstone formation is associated with poorer contractility and larger volume in gallbladders that contain stones.

- Citation: Huang SM, Yao CC, Pan H, Hsiao KM, Yu JK, Lai TJ, Huang SD. Pathophysiological significance of gallbladder volume changes in gallstone diseases. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(34): 4341-4347

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i34/4341.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i34.4341

Gallbladder volume (GBV) can reflect clinical and therapeutic implications, physiological and functional status, and possibly pathophysiological mechanisms of gallstone diseases. In 1880, Courvoisier and Terrier’s law stated that large painless, palpable gallbladder was mostly due to malignant obstruction of the bile duct[1]. In 1963, Maingot found that tensely swollen, tenderly palpable gallbladder in acute cholecystitis was due to stone impaction in the cystic duct[2]. In 1989, Masclee noted, in one third of patients with cholesterol gallstones, increased GBV and delayed gallbladder emptying were present at the postprandial phase[3-5]. In 2000, Portincasa demonstrated in a comparative study that patients with cholesterol gallstones showed significantly larger fasting volume and postprandial volume of gallbladders than did controls and patients with pigment stones at each time point during a 2-h study[6]. He proposed that larger GBV predisposes to bile stasis.

However, the differences and changes in GBV among different age groups in non-gallstone subjects, and their correlations with the formation of gallstones have not been reported previously. Also, the correlations between GBV changes at different stages in the pathophysiological development of acute cholecystitis in gallstone patients are not clear. Furthermore, we wished to investigate the possible reciprocal correlation between GBV and gallbladder contractibility.

The aims of this study were to study the pathophysiological significance of gallbladder volume and ejection fraction changes in gallstone patients by comparing the GBV among gallstone patients with acute cholecystitis, chronic cholecystitis, contracted gallbladder and non-gallstone subjects, and by comparison between gallstone patients with chronic cholecystitis and non-gallstone subjects with different ages and sex. Furthermore, to investigate the correlations between gallbladder physiological changes and the development of gallstones, we further investigated the differences in gallbladder contractility between gallstone patients with chronic cholecystitis and normal subjects.

Between October 1, 2007 and September 30, 2008, 99 gallstone patients with acute cholecystitis, 85 gallstone patients with chronic cholecystitis, and five patients with gallbladder contraction were admitted to Chung Shan Medical University Hospital to undergo cholecystectomy.

Acute cholecystitis: The clinical imaging findings of acute cholecystitis in abdominal ultrasonography include thick gallbladder wall (> 3 mm), stones in the gallbladder, distended gallbladder with pericholecystic fluid, and sonographic Murphy’s sign with tenderness over the gallbladder from the ultrasound transducer. The pathological features of acute cholecystitis include leukocyte infiltration throughout the tissues, local flattening and denuded mucosal folds, and tissue edema. If untreated or treated late, localized regions of necrosis (gangrene) or abscess formation (empyema) can be found.

Chronic cholecystitis: The pathological features of chronic cholecystitis include subserosal fibrous tissues, lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages found beneath the columnar epithelium, and Rokitansky-Aschoff sinus in the muscular layer.

Gallbladder contraction: Gallbladder contraction is known to result from long-standing chronic cholecystitis. Anatomical characteristics include severe adhesions and complete coverage by greater omentum, severe pericholecystic fibrosis, thickening of gallbladder walls (usually thicker than 5 mm), loss of elasticity, obscure anatomy at triangle of Calot, dense adhesions to the duodenum, transverse colon and common hepatic duct, and small GBV (usually < 10 mL).

Non-gallstone controls: We randomly chose 240 patients who received abdominal computed tomography (CT) for non-gallstone reasons between July 1, 2008 and July 31, 2008.

Demographic data: The age, sex, associated diseases and previous operations for all patients were recorded. The procedures included preoperative CT measurement of gallbladder diameter, and directly measured gallbladder diameter. Directly measured GBV by the saline-filling method in patients with gallstones and acute and chronic cholecystitis were also recorded. The CT measurements of non-gallstone controls were also recorded. The GBV was calculated from the gallbladder lengths and short axis diameters by the equation shown below.

GBV measurements and calculations: We measured the lengths and short axis diameters of the fasting gallbladder of patients from their preoperative CT films, measured the lengths and short axis diameters directly after their removal in the operating room, and recorded their lengths and short axis diameters measured by the pathologist postoperatively. We then calculated the GBV according to the equation: GBV (cm3) = 4/3 ×π× r1 × r2 × r3/costheta;, where r1, r2 and r3 represent the three greatest radii of the gallbladder ellipsoid and theta; is the angle between the z axis of the gallbladder and the z axis of the transverse cross sectional CT imaging.

We also measured directly the GBV after the gallbladders were removed. After withdrawing the gallbladder bile with a syringe, the volume of normal saline injected into the intact gallbladders was added to the volume of gallbladder stones measured after opening the GB walls. Comparing the GBV obtained by direct measurement and calculations using the various techniques, correction factors for different measuring methods were obtained to modify the calculated GBV, thus minimizing the measurement bias.

The gallbladder is a pear-shaped organ located under the liver, which stores bile. It can be approximated to an ellipsoid shape. The volume of an ellipsoid can be obtained as follows[8]: Claim area for ellipse is π r1 r2: given an ellipse x2/r12 + x2/r22 = 1. Since an ellipse is symmetric to the x and y axes, Area = 4∫r10 r2 (1 - x2/r12)1/2 dx = 4r2/r1∫r10 (r12- x2)1/2 dx. (Let x = r1sintheta;, then dx = r1costheta;dtheta;, where -π/2 < theta; < π/2) = 4r2/r1∫π/20 (r12- r12sin2theta;)1/2 r1costheta; dtheta; = 4r1r2∫π/20 cos2theta;dtheta; = 4r1r2∫π/201/2 (1 + cos2theta;) dtheta; = 2 r1r2 [theta; + 1/2sin2theta;]π/20 = π r1r2 = > For a slice of ellipse of the ellipsoid parallel to the yz plane, the radius parallel to the z axis is g (z) = r1 (1 - z2/r32)1/2. Similarly, its radius parallel to the y axis is h (z) = r2 (1 - z2/r32)1/2. Thus, the volume V of the ellipsoid = ∫r3 - r3π g (z) h(z)dz = ∫r3 - r3π r1 (1 - z2/r32)1/2 r2 (1 - z2/r32)1/2 dz =π r1 r2∫r3 - r3 (1 - z2/r32) dz =π r1 r2 [z - z3/3r32]r3 - r3 = 4/3π r1r2r3 #.

theta;: The gallbladder does not always lie in the same plane, therefore, the measured GBV is corrected by multiplying a correction factor 1/cos theta;, where theta; is the angle between the z axis of the gallbladder and the z axis of the transverse cross sectional CT imaging and 0°≤ theta; < 90°.

c = 0.82 ± 0.40 (n = 65): CT measurement correction factor = (Direct measurement calculated GBV)/(CT measurement calculated GBV).

p = 0.85 ± 0.42 (n = 65): Pathology measurement correction factor = (Pathology measurement calculated GBV)/(Direct measurement calculated GBV).

s = 0.88 ± 0.36 (n = 65): Shueh-Ding correction factor = (Direct injection measurement GBV)/(Direct measurement calculated GBV).

Direct measurement GBV = Direct measurement calculated GBV × 0.88 (s, Shueh-Ding correction factor).

u = 0.90 (n = 65): Ultrasound (US) measurement correction factor = (Direct measurement calculated GBV)/(US measurement calculated GBV).

Direct injection measurement GBV = Direct measurement calculated GBV × s = CT measurement calculated GBV × cs (cs = 0.72 = 0.82 × 0.88) = US measurement calculated GBV × us (us = 0.79 = 0.9 × 0.88).

Substudy on gallbladder contractility: To investigate and compare the gallbladder contractility between patients with gallstones and chronic cholecystitis and normal subjects, and the possible reciprocal correlation between GBV and gallbladder contractility, we designed and conducted a subsequent second study. Between October 1, 2008 and June 30, 2009, we measured the fasting and postprandial GBV of 65 patients with gallstones and chronic cholecystitis and 53 healthy subjects, by abdominal ultrasonography.

Study protocol: Subjects came to the hospital after an overnight fast.

They were reminded the night before the study not to eat or drink after supper. Their adherence to this instruction was confirmed by performing a history taking to make sure that the subjects did adhere to the investigator’s instructions, including nothing by mouth after the previous supper. Gallbladder size was determined in the fasting state. The subjects then drank a standard liquid meal with a total 420 kcal: 30% as fat, 15% as protein, and the rest as carbohydrate. The postprandial gallbladder size was measured and GBV was calculated 90 min after the meal[9].

Ultrasound technique: The abdominal sonography was performed by the same investigator (Huang SM) with techniques modified from the literature[9]. The hand-held transducer was placed in a sagittal longitudinal projection in the right-upper quadrant and rotated until the largest longitudinal dimension of the gallbladder was obtained on the oscilloscope screen. The image was frozen, measured by electronic calipers, and photographed. The transducer was then rotated 90° and the largest short axis through the gallbladder was obtained. Occasionally, deep inspiration was required, but all patients were successfully examined. We used three dimensions - length, lateral and antero-posterior diameters - to calculate the GBV, which was modified empirically as described above.

The ejection fraction (EF) of the gallbladder was calculated by the following equation: EF (%) = [Fasting GBV (mL) - Postprandial GBV (mL)]/[Fasting GBV (mL)] × 100.

Statistics: We compared the GBV measurements and patient age using Student’s unpaired t test, and the χ2 test to compare the sex differences. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

We found a male predominance in the acute cholecystitis group and a female predominance in the chronic cholecystitis group: male/female (M/F) = 53/46 and 32/53, respectively (P = 0.04 by χ2 test). There was no sex difference between patients in the chronic cholecystitis group and the non-gallstone group (M/F = 32/53 vs 117/123, P = 0.10). There was no age difference among patients in the acute cholecystitis group, the chronic cholecystitis group and the non-gallstone group (57 ± 17 years, 53 ± 15 years and 54 ± 18 years, P = 0.09 and 0.64, respectively). Associated diseases and previous operations undergone for all patients and normal subjects included cerebral vascular accident (3), diabetes mellitus (4), pneumonia (1), hyperlipidemia (1), hypertensive cardiovascular diseases (5), status/post exploratory laparotomy (2) and coronary artery disease (5) in the gallstones patients with acute cholecystitis; diabetes mellitus (5) and manic-depressive psychosis (1) and status/post gastrectomy/vagotomy (2) in the gallstones patients with chronic cholecystitis; and liver tumor (2), liver cysts (5), diabetes mellitus (9), hypertensive cardiovascular diseases (10) and status/post exploratory laparotomy (5) in the non-gallstone group. The GBV in the diabetic and non-diabetic non-gallstone patients did not differ significantly (16.18 ± 2.79 cm3, n = 9 vs 16.79 ± 9.43 cm3, n = 231, P = 0.85). The GBV in the s/p gastrectomy/vagotomy and non-s/p gastrectomy/vagotomy, non-gallstone patients did not differ significantly either (19.85 ± 3.41 cm3, n = 2 vs 16.74 ± 9.30 cm3, n = 238, P = 0.64). Thirty patients in the acute cholecystitis group underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy. They comprised 30.3% (30/99) of the acute cholecystitis patients. Seventy-seven patients in the chronic cholecystitis group underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy. They comprised 90.6% (77/85) of the chronic cholecystitis patients. The remaining 77 patients underwent open cholecystectomy.

The fasting GBV in gallstone patients with acute cholecystitis (n = 99), chronic cholecystitis (n = 85), gallbladder contraction (n = 5) and non-gallstone subjects (n = 240) was 57.00 ± 41.20 cm3, 28.77 ± 15.00 cm3, 6.15 ± 2.52 cm3 and 16.77 ± 15.75 cm3, respectively (Table 1). The average fasting GBV was larger in gallstone patients with acute cholecystitis than that with chronic cholecystitis (P < 0.0001). In turn, the average fasting GBV was larger in gallstone patients with chronic cholecystitis than in non-gallstone subjects (P < 0.0001, Table 1).

In non-gallstone subjects, there was a significant difference in the fasting GBV between two age groups, i.e. age ≤ 20 years vs 20-40 years (6.33 ± 2.75 cm3, n = 9 vs 16.84 ± 4.04 cm3, n = 35, P = 0.0070) and age 40-60 years vs 60-80 years (15.12 ± 7.55 cm3, n = 106 vs 19.83 ± 9.99 cm3, n = 81, P < 0.0003) (Table 2). The fasting GBV had a tendency to increase with age. In accordance with this tendency, the occurrence of gallstones with chronic cholecystitis also increased with age (P = 0.0027 by Fisher’s exact test, Table 2).

In the second substudy, the average fasting/postprandial GBV in patients with gallstones and chronic cholecystitis was 31.44 ± 16.46 cm3/20.50 ± 6.20 cm3. The average gallbladder EF of patients with gallstones and chronic cholecystitis was 34.6% ± 10.6% (n = 65). The average fasting/postprandial GBV in normal subjects was 19.22 ± 11.30 cm3/9.03 ± 3.63 cm3. The average EF of normal gallbladder was 53.3% ± 24.9% (n = 53). The differences in the average fasting, postprandial GBV and EF were statistically significant (all three P < 0.0001, Figure 1, Table 3). Also, the differences in GBV between fasting and postprandial states in patients with gallstones and chronic cholecystitis and normal subjects were statistically significant (both P < 0.0001).

The fasting GBV was larger in late stage than early/second stage acute cholecystitis in gallstone patients (84.66 ± 26.32 cm3, n = 12, vs 53.19 ± 33.80 cm3, n = 87, P = 0.002, Table 4). The average fasting GBV was larger (28.77 ± 15.00 cm3vs 6.77 ± 15.75 cm3, P < 0.0001) and the average EF was lower (34.6% ± 10.6%, n = 65, vs 53.3% ± 24.9%, n = 53, P < 0.0001, Table 3) in gallstone patients with chronic cholecystitis, compared with those in non-gallstone and normal subjects.

| Variable GS patients | Mean GBV±SD (cm3) (n) | 1P-value A vs B (A-B, 95% CI) |

| Simple ACC | A53.19 ± 33.80 | 0.002 |

| (87) | (12.28-52.66) | |

| With gangrene/abscess | B84.66 ± 26.32 | |

| (12) |

From clinical observations, male patients with gallstone disease seem to have a higher threshold for pain caused by biliary stones than their female counterparts. Perhaps this is one of the reasons that underlay the male preponderance seen in the acute calculous cholecystitis group in this study.

Our study showed that the fasting GBV increased in two age groups in non-gallstone subjects, i.e. from age 20 to 40 years and 60 to 80 years; especially the former period. In accordance with this differential increase in GBV in specific periods, the occurrence of gallstones reached its plateau between 40 and 80 years of age (from 15% before 40 years old to 42.5% after 40 years, P = 0.0027, Table 2).

The gallbladder is a hollow visceral elastic organ. Its actual maximal fasting volume under in vivo physiological conditions is difficult to measure. Measuring methods include in vivo ultrasonography, nuclear scintigraphy, CT and in vitro post-cholecystectomy saline-filling measurement. hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scintigraphy is seldom used clinically except to demonstrate cystic duct obstruction in acute cholecystitis patients, due to its isotope radioactivity. On the other hand, in vitro post-cholecystectomy saline-filling measurement is the most accurate gold standard for measuring GBV. In contrast, abdominal ultrasonography is the most convenient examination for measuring GBV. However, the accuracy and precision depend greatly on the operators’ individual experiences. CT represent the more uniform, constantly used and easier method for diagnosis of gallstone diseases and for measuring GBV. These are the reasons why we adopted abdominal ultrasonography, CT and in vitro post-cholecystectomy saline-filling measurement in the present study.

GBV can have clinical and therapeutic implications and reflect pathophysiological mechanisms of gallstone diseases. The clinical and therapeutic implications of increased GBV lie in the cystic duct obstruction in acute calculous cholecystitis. The dilatation of the gallbladder is due to stones being trapped in the spiral valve of Heist. The onset of painful dilatation of the gallbladder is acute and is caused by the stones irritating the gallbladder mucosa, and the pressure exerted by the dilated gallbladder on the visceral nerve endings distributed over the entire gallbladder wall. Early dilatation of the gallbladder due to undrained mucus secretions also predisposes to compromised local blood circulation to the mucosa and the gallbladder wall, which leads to impaired absorption of water and electrolytes, which further aggravates the dilatation[10-12]. GBV can usually reach up to 3.4 times the normal size. The vicious cycle of undrained mucus secretions and impaired absorption of water and electrolytes, coupled with chemical irritation by lysozyme, cytokines and chemokines, sometimes causes gangrene and/or perforation in 15% and 1.5%, respectively, of patients with acute calculous cholecystitis[2].

In our study, the fasting GBV was larger in gallstone patients with acute cholecystitis than with chronic cholecystitis (Table 1). Furthermore, local gallbladder wall necrosis/abscess was associated with further increases in GBV (Table 4). It is possible that gallbladder decompression might prevent gangrene/empyema and perforation and make it easier to manipulate the gallbladder during cholecystectomy.

Gallbladder contraction is known to result from long-standing chronic cholecystitis and has the smallest GBV. The anatomical characteristics make it a difficult challenge to perform laparoscopic cholecystectomy safely.

The fasting GBV was larger in gallstone patients with chronic cholecystitis than that in non-gallstone subjects (28.77 ± 15.00 cm3, n = 85, vs 16.77 ± 15.75, n = 240, P < 0.0001), which indicated possible pathophysiological mechanisms of weaker gallbladder contractility in gallstone patients with chronic cholecystitis, which was confirmed in our second study. In 2000, Portincasa proposed that larger GBV predisposes to bile stasis[6].

Weaker gallbladder contractility in gallstone patients with chronic cholecystitis might provide a suitable micro-milieu for cholesterol monohydrate micro-crystals to grow into larger gallbladder stones, by preventing them from expulsion from the gallbladder lumen, when the gallbladder contracts in response to cholecystokinin (CCK) secreted from duodenum I cells stimulated by proteins and lipids in ingested food[8].

In our second study, we measured fasting and postprandial GBV of 65 patients with gallstones and chronic cholecystitis and 53 healthy subjects, by abdominal ultrasonography and calculated the gallbladder EF. The average EF of patients with gallstones and chronic cholecystitis was lower than that of the healthy subjects. The difference in EF was statistically significant (Table 3).

From our observations on the GBV changes during the development of acute cholecystitis from a chronic inflammatory state, we hypothesize that there are three stages based on GBV and pathological changes. These correspond to the three stages of severity of acute cholecystitis proposed by Miura et al[13] at the Tokyo International Consensus Meeting in 2007.

In the early (clinical) stage of acute cholecystitis, which corresponds to mild (grade I) severity in the Tokyo consensus meeting, the mechanical effect of cystic duct obstruction causes an increase in GBV (from 28.77 ± 15.00 cm3, n = 85, to 54.16 ± 35.17 cm3, n = 44, P < 0.0001). No acute inflammatory leukocyte infiltration is observed, but chronic inflammatory reactions, such as subserosal fibrous tissues, and infiltration of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages beneath the columnar epithelium and Rokitansky-Aschoff sinus in the muscular layer are present, as revealed by pathological examinations. The early (clinical) stage of acute cholecystitis comprises about 44.4% (44/99). Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy is suggested by the Tokyo guidelines.

In the second (pathological) stage of development, which corresponds to the moderate severity (grade II) stage of the Tokyo guidelines, the GBV does not change significantly. However, pathological findings of acute immunoreactive and inflammatory responses appear in the gallbladder. These include leukocyte infiltration throughout the tissues, local flattening and denuded mucosal folds, and tissue edema. It comprises about 43.4% (43/99). Early laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy is suggested by the Tokyo guidelines. If a patient has serious local inflammation that makes early cholecystectomy difficult, then percutaneous or operative drainage of the gallbladder is recommended. Elective cholecystectomy can be performed after improvement of the acute inflammatory process.

If the condition goes untreated or is unresolved by treatment, the late (complicated) stage ensues, which corresponds to the severe (grade III) organ dysfunction stage of the Tokyo guidelines. In this stage, GBV further increases (Table 4). Besides the pathological findings of acute immunoreactive and inflammatory responses, local gallbladder wall necrosis (gangrene), abscess and/or even perforations occur. Organ dysfunctions appear. It comprises about 12.2% (12/99). Appropriate organ support in addition to medical treatment for patients with organ dysfunction is suggested by the Tokyo guidelines. Management of severe local inflammation by percutaneous gallbladder drainage and/or cholecystectomy is needed. Biliary peritonitis due to perforation of the gallbladder is an indication for urgent cholecystectomy and drainage. Elective cholecystectomy may be performed after improvement of the acute illness by gallbladder drainage[13].

Zhu et al[14] have found that the amount of gallbladder CCK receptor is lower in patients with gallstones who have poor gallbladder contraction. Choi has found that FGF15 knockout mice have a gallbladder that is completely devoid of bile, and administration of recombinant FGF15 or FGF19 restores the GBV[8,15]. Whether gallstone patients with poor gallbladder contraction and increased GBV have lower levels of CCK receptor and/or lower FGF19 gene expression is worth further investigation.

Different kinds of diet predispose humans to different gallstone diseases. At present, we have no data concerning how the diet consumed by the gallstone patients was different from that consumed by the normal population. If the diet differs, it is worthwhile investigating whether the diet predisposes the patients to gallstone diseases through its effect on GBV.

There is a limitation to this study. The gallstone patients were not subgrouped into those with cholesterol and pigment stones. Therefore, the findings of Masclee[3-5] and Portincasa[6] could not be investigated in this study.

In summary, we found that the fasting GBV increased in two periods in non-gallstone subjects, i.e. from age 20 to 40 years and 60 to 80 years. In accordance with these age preferences, the occurrence of gallstones reached its peak between 40 and 80 years of age. Moreover, we found that gallstone formation was associated with poorer gallbladder contractility and larger fasting and postprandial GBV Also, GBV increased as acute cholecystitis progressed. Therefore, gallbladder decompression is mandatory to prevent gangrene and/or empyema of gallbladders.

Gallbladder volume (GBV) changes can have clinical and therapeutic implications, and reflect physiological and functional status, and possibly pathophysiological mechanisms of gallstone diseases. However, the differences and changes in GBV among different age groups in non-gallstone subjects and their correlations with the formation of gallstones have not been reported previously. Also, the correlations between GBV changes in different stages in the pathophysiological development of acute cholecystitis in gallstone patients are not clear. Furthermore, the authors wished to investigate the possible reciprocal correlation between GBV and gallbladder contractility. The methodology used to measure in vivo GBV is hardly reported in the literature.

The methods the authors developed in this study can provide a reliable method to measure the in vivo GBV in a way that can be adjusted to approximate the direct measurements by the saline injection method. In this study, the authors found that GBV increased as acute cholecystitis progressed to gangrene and/or empyema. The fasting volume of gallbladders was larger in late stage than in early/second stage acute cholecystitis. This forms the pathophysiological basis for the guidelines suggested by the Tokyo International Consensus Meeting in 2007.

This is believed to be the first study to report the differential increase in GBV in specific age groups, which coincides with and partly explains the high occurrence rate of gallstones, which reached their plateau between 40 and 80 years of age. This is also believed to be the first study to demonstrate one of the pathophysiological mechanisms that underlie the development of acute calculous cholecystitis, which form the basis for the severity staging system in the Tokyo International Consensus Meeting.

An interesting area of future investigation would be to apply the authors' measurements and gallbladder emptying assessment to patients without gallstone disease but with right upper quadrant pain. By contributing to the authors’ understanding of how acute calculous cholecystitis develops, this study could represent a rationale for therapeutic decompression intervention, by drainage or straight cholecystectomy, in the treatment of patients with acute calculous cholecystitis.

The reviewer found that this was an interesting study that was performed well. Also, the reviewer wonders what the diet was like in the normal and diseased populations, because that would have an effect on GBV. This is a good contribution to a topic that has not been described previously.

| 1. | Cervantes J. Common bile duct stones revisited after the first operation 110 years ago. World J Surg. 2000;24:1278-1281. |

| 2. | Maingot R. Types of cholecystitis: the management of acute cholecystitis and chronic calculous cholecystitis. Abdominal operations. 7th ed. East Sussex, England: Appleton-Century-Crofts 1980; 1012-1023. |

| 3. | Masclee AA, Jansen JB, Driessen WM, Geuskens LM, Lamers CB. Plasma cholecystokinin and gallbladder responses to intraduodenal fat in gallstone patients. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:353-359. |

| 4. | Stolk MF, van Erpecum KJ, Renooij W, Portincasa P, van de Heijning BJ, vanBerge-Henegouwen GP. Gallbladder emptying in vivo, bile composition, and nucleation of cholesterol crystals in patients with cholesterol gallstones. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:1882-1888. |

| 5. | van Erpecum KJ, van Berge Henegouwen GP, Stolk MF, Hopman WP, Jansen JB, Lamers CB. Fasting gallbladder volume, postprandial emptying and cholecystokinin release in gallstone patients and normal subjects. J Hepatol. 1992;14:194-202. |

| 6. | Portincasa P, Di Ciaula A, Vendemiale G, Palmieri V, Moschetta A, Vanberge-Henegouwen GP, Palasciano G. Gallbladder motility and cholesterol crystallization in bile from patients with pigment and cholesterol gallstones. Eur J Clin Invest. 2000;30:317-324. |

| 7. | Etgen SH. Calculus II. In: Salas SL, Etgen GJ, Hille E., editors. Calculus, One and Several Variables, 9th ed 2004; 314, 945-950, 985-986. |

| 8. | Portincasa P, Di Ciaula A, Wang HH, Palasciano G, van Erpecum KJ, Moschetta A, Wang DQ. Coordinate regulation of gallbladder motor function in the gut-liver axis. Hepatology. 2008;47:2112-2126. |

| 9. | Braverman DZ, Johnson ML, Kern F Jr. Effects of pregnancy and contraceptive steroids on gallbladder function. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:362-364. |

| 10. | Nakanuma Y, Katayanagi K, Kawamura Y, Yoshida K. Monolayer and three-dimensional cell culture and living tissue culture of gallbladder epithelium. Microsc Res Tech. 1997;39:71-84. |

| 11. | Carey MC, Cahalane MJ. Whither biliary sludge? Gastroenterology. 1988;95:508-523. |

| 12. | Sherlock S, Dooley J. Diseases of the Liver and Biliary System. 11th ed. London: Blackwell 2002; 610-612. |

| 13. | Miura F, Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Wada K, Hirota M, Nagino M, Tsuyuguchi T, Mayumi T, Yoshida M. Flowcharts for the diagnosis and treatment of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis: Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:27-34. |

| 14. | Zhu J, Han TQ, Chen S, Jiang Y, Zhang SD. Gallbladder motor function, plasma cholecystokinin and cholecystokinin receptor of gallbladder in cholesterol stone patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:1685-1689. |

Peer reviewer: Florencia Georgina Que, MD, Department of Surgery, Mayo Clinic, 200 First Street Southwest, Rochester, MN 55905, United States

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Ma WH