Published online Sep 14, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i34.4291

Revised: May 15, 2010

Accepted: May 22, 2010

Published online: September 14, 2010

AIM: To evaluate the ability of contrast-enhanced computerized tomography (CECT) to characterize the nature of peripancreatic collections.

METHODS: Twenty five patients with peripancreatic collections on CECT and who underwent operative intervention for severe acute pancreatitis were retrospectively studied. The collections were classified into (1) necrosis without frank pus; (2) necrosis with pus; and (3) fluid without necrosis. A blinded radiologist assessed the preoperative CTs of each patient for necrosis and peripancreatic fluid collections. Peripancreatic collections were described in terms of volume, location, number, heterogeneity, fluid attenuation, wall perceptibility, wall enhancement, presence of extraluminal gas, and vascular compromise.

RESULTS: Fifty-four collections were identified at operation, of which 45 (83%) were identified on CECT. Of these, 25/26 (96%) had necrosis without pus, 16/19 (84%) had necrosis with pus, and 4/9 (44%) had fluid without necrosis. Among the study characteristics, fluid heterogeneity was seen in a greater proportion of collections in the group with necrosis and pus, compared to the other two groups (94% vs 48% and 25%, P = 0.002 and 0.003, respectively). Among the wall characteristics, irregularity was seen in a greater proportion of collections in the groups with necrosis with and without pus, when compared to the group with fluid without necrosis (88% and 71% vs 25%, P = 0.06 and P < 0.01, respectively). The combination of heterogeneity and presence of extraluminal gas had a specificity and positive likelihood ratio of 92% and 5.9, respectively, in detecting pus.

CONCLUSION: Most of the peripancreatic collections seen on CECT in patients with severe acute pancreatitis who require operative intervention contain necrotic tissue. CECT has a somewhat limited role in differentiating the different types of collections.

- Citation: Vege SS, Fletcher JG, Talukdar R, Sarr MG. Peripancreatic collections in acute pancreatitis: Correlation between computerized tomography and operative findings. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(34): 4291-4296

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i34/4291.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i34.4291

Pancreatic necrosis and so called peripancreatic “fluid” collections are local complications of acute pancreatitis (AP) defined according to the Atlanta Criteria of AP, which categorizes AP as severe if these complications are present. It has been estimated that about 15% (4%-47%) of patients with AP will have necrotizing pancreatitis[1]; and 21%-46%[2-4] of patients will develop a peripancreatic “fluid” collection, including acute collections (during the first 4-6 wk), pseudocysts (after 4-6 wk of an acute attack with a defined wall with no or little necrotic tissue), necrotic collections and abscesses (collection after 4-6 wk with pus and a defined wall), according to the definitions of the Atlanta Classification. Earlier studies have demonstrated good correlation between contrast-enhanced computerized tomography (CECT) and operative findings with regard to pancreatic parenchymal necrosis in patients with AP[5-8]. Lack of vascular-based enhancement of the pancreatic parenchyma is the most characteristic finding on CECT that would suggest the presence of pancreatic parenchymal necrosis; and it has been suggested that the degree of pancreatic necrosis has important prognostic implications[9]. Problems, however, have been evident with much of the nomenclature of the Atlanta Classification with our more current understanding of the spectrum of necrotizing pancreatitis. The nomenclature of peripancreatic fluid collection is confusing due to various terms (as described above) and their clinical significance. It is not always possible in the first 4-6 wk to distinguish on CECT simple fluid collections (associated with acute edematous pancreatitis and better outcomes) from necrotic collections (associated with necrotizing pancreatitis and worse outcomes). No specific CT features that could detect necrosis of peripancreatic tissues (so called peripancreatic necrosis) have been reported so far. Moreover, studies evaluating CECT and operative correlation in the detection of peripancreatic necrosis and peripancreatic fluid collections are scant. Sarr et al[7] suggested that peripancreatic necrosis may not be seen on CECT and that a normal enhancement of the pancreas does not necessarily rule out the presence of peripancreatic necrosis. Therefore, assessment of the nature of these peripancreatic collections can be difficult even though these collections are fairly well imaged by CECT.

In this study, we evaluate the correlation between CT findings of peripancreatic collections and findings at operation and thereby assess the ability of CECT to characterize the nature of these peripancreatic collections. We have consciously and purposely elected to call the peripancreatic collections, not peripancreatic “fluid” collections, but peripancreatic “collections” because of the apparent difficulty of differentiating true fluid collections from necrotic areas and necrotic areas with some liquefaction necrosis. Thus, we will not refer to these collections as peripancreatic fluid collections as was done in the Atlanta Classification.

In this retrospective study, we evaluated 25 patients who had one or more peripancreatic collections on CECT and who underwent operative intervention for severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) between 1995 and 2001 at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester. Severity of acute pancreatitis was determined according to the Atlanta Criteria. The CT slice thickness was 7 mm. Operative findings were used as an objective, gold standard for defining the nature of the peripancreatic collections. A single surgeon (MGS), blinded to the CT findings, interpreted the surgical notes and classified the peripancreatic collections into the following three groups: (1) necrosis without frank pus; (2) necrosis with pus; and (3) fluid without necrosis. The nomenclature of pancreatic collections is currently undergoing a revision (International Working Group); indeed the above three terms could mean the previous entities, peripancreatic necrosis, peripancreatic necrosis with pus, and pseudocysts. The presence of necrosis was confirmed from the operative findings and histopathologic review of the surgical specimens. Following this, a single radiologist (JGF), blinded to the operative findings, assessed the preoperative CTs of each patient for necrosis and peripancreatic collections. Pancreatic parenchymal necrosis was assessed in terms of extent (no necrosis, 30% necrosis, 30%-50% necrosis and > 50% necrosis), and location. Peripancreatic collections were described in terms of volume, location, number, heterogeneity, fluid attenuation, wall perceptibility, wall enhancement, presence of extraluminal gas, and vascular compromise. The volumes of the collections on CECT were measured using the formula π/6 × (d1 × d2 × d3), with d representing the maximum diameters in three different planes. Thereafter, the locations of the collections seen on CECT were matched to those identified at operation as per the operative notes. When two collections on CECT matched with only one collection seen at operation, then one of the collections on CT was randomly selected for further evaluation. If collections seen on CT did not match with collections seen at operation, they were excluded from further consideration.

Other parameters that were retrieved from the charts included demographic variables, presence of organ failure, presence of infection in the different groups of peripancreatic collections, and mortality. Approval by the Mayo Institutional Review Board approval was obtained prior to the study.

A database was generated in Microsoft Excel, and subsequently all statistical analyses were performed using the JMP software (version 7) from the SAS Institute, NC, USA. Continuous variables were expressed as median (IQR) and categorical variables as percentage. The different CT characteristics between the three groups of peripancreatic collections were compared by the chi square test (with Yates correction wherever applicable) and ordinal variables were analyzed with the Wilcoxon rank test. The ‘t’ test was applied to compare continuous variables. A ‘P’ value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

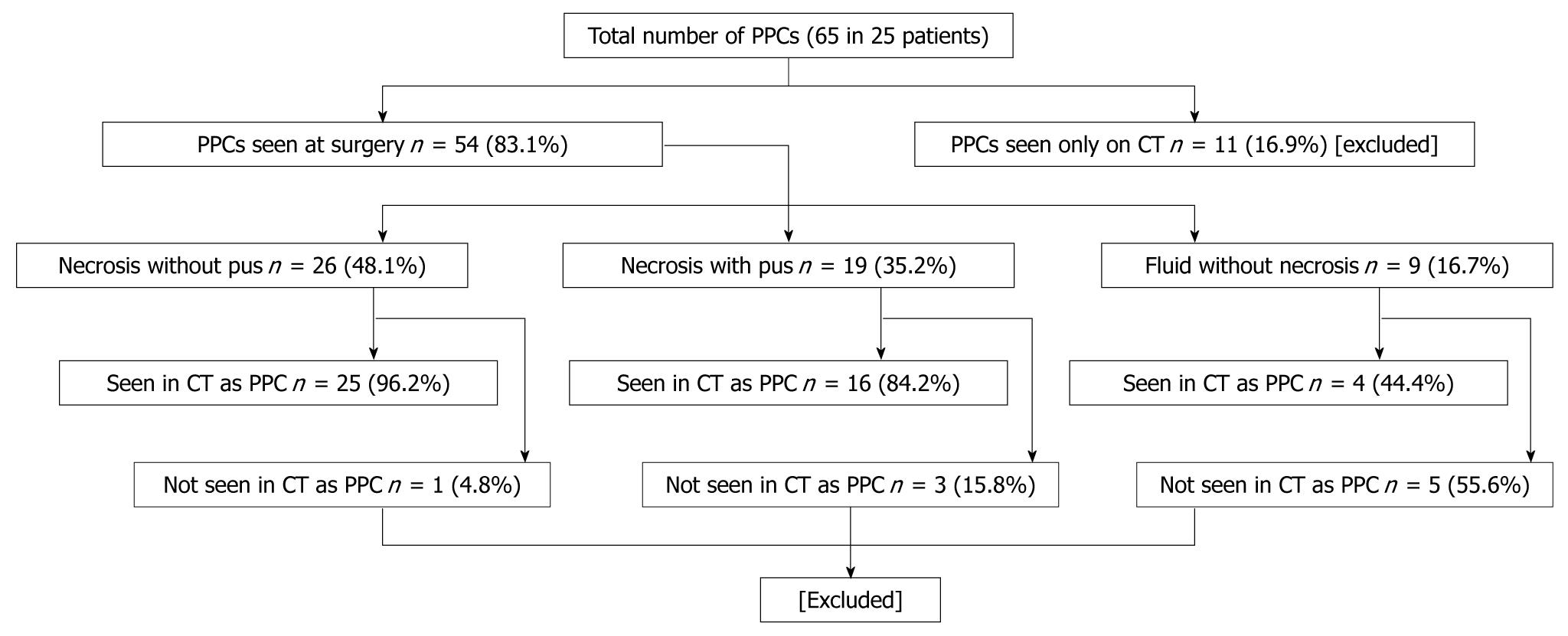

We evaluated 25 individuals who had a total of 65 collections, of which 54 were identified specifically at operation. These patients underwent surgery because they had either deterioration in clinical and laboratory parameters or they had evidence of sepsis. Table 1 shows the patient characteristics and Figure 1 shows the distribution of the different types of peripancreatic collections.

| Parameters | |

| Median (IQR) age (yr) | 54 (50-67) |

| Male patients, n (%) | 20 (80) |

| Contrast-enhanced CT, n (%) | 23 (92) |

| Median (IQR) No. of PPCs | |

| Necrosis without pus | 2 (1-2) |

| Necrosis with pus | 1 (1-2) |

| Fluid without necrosis | 1 (1-3) |

| Infected PPC, n (%) | 12 (48) |

| OF in patients with PPC | |

| Total, n (%) | 19 (76) |

| Persistent OF (> 48 h), n (%) | 15 (60) |

| Multiple OF, n (%) | 2 (8) |

| Mortality, n (%) | 3 (12) |

We analyzed only the peripancreatic collections that were evaluated at operative exploration. Of the 54 seen at operation, 26 had necrosis without pus, 19 had necrosis with pus, and 9 had fluid without necrosis. Forty five (83%) of 54 collections were identified on CECT, among which 25/26 (96%) had necrosis without pus, 16/19 (84%) had necrosis with pus, and 4/9 (44%) had fluid without necrosis. Therefore, the majority (n = 41, 91%) of the collections seen on CT were actually peripancreatic necrosis when correlated with operative findings. Among the 54 collections seen at operative exploration, 9 (17%) could not be identified as discrete collections on CT (Figure 2). Five (55%) of these 9 collections had associated necrosis, and 4 (44%) had only fluid without necrosis and were read as ascites on CT.

Eighteen (72%) out of 25 patients had pancreatic parenchymal necrosis. Among these patients, 9 (50%) had < 30% necrosis, 4 (22%) had 30%-50% necrosis, and 5 (28%) had > 50% necrosis. We did not observe a statistically significant relationship between the percentage and location of pancreatic necrosis and the number and size of peripancreatic collections.

All peripancreatic collections were seen around the pancreas, except for one collection in the group with necrosis without pus, which was present in the lower abdomen in the retroperitoneum. Among the characteristics studied, fluid heterogeneity was seen in a greater proportion of collections in the group with necrosis and pus, compared to the other two groups (94% vs 48% and 25%, P = 0.002 and 0.003, respectively); however, there was no difference in heterogeneity between the groups with necrosis without pus and fluid without necrosis (48% vs 25%, P = 0.39). Attenuation units were similar in all three groups (Table 2).

| Necrosis without pus (n = 25) | Necrosis with pus (n = 16) | Fluid without necrosis (n = 4) | ‘P’ value | ||

| Volume in cm3, median (IQR) | 193.4 (50-1129) | 116.3 (88-389) | 551.7 (324-937) | ||

| Fluid characteristics | Heterogeneity, n (%) | 12 (48) | 15 (93.8)c | 1 (25)a | 0.0041 |

| Fluid attenuation, n (%) | 21 (84) | 13 (81.3) | 4 (100) | 0.69 | |

| Wall characteristics | Perceptible, n (%) | 23 (92) | 14 (88) | 4 (100) | 0.76 |

| Enhancing, n (%) | 21 (84) | 14 (88) | 4 (100) | 0.68 | |

| Irregular, n (%) | 18 (71) | 14 (88) | 1 (25)a | 0.05 | |

| Internal air, n (%) | 4 (16) | 9 (56)c | 0 (0)a | 0.0091 | |

| Vessel involvement, n (%) | 5 (20) | 3 (19) | 0 (0) | 0.62 |

Among the characteristics of the “wall” of the collections studied, irregularity of the wall was seen in a greater proportion of collections in the groups with necrosis with and without pus, when compared to the group with fluid without necrosis (88% and 71% vs 25%, P = 0.06 and P < 0.01, respectively). This finding was not different between the groups with necrosis with and without pus (88% vs 71%, P = ns). The other wall characteristics, i.e. perceptibility and enhancement, were similar in all three groups. Two patients with necrosis and pus could not have intravenous contrast administered during CT due to renal failure; when these two patients were excluded from the group while comparing the wall characteristics, the results were unchanged.

The presence of internal, extraluminal gas was seen only in collections with necrosis and in a greater proportion of collections in the group with necrosis and pus when compared to the other two groups (56% vs 16% and 0%, P < 0.01 in each). In the group with necrosis and pus, the proportion of collections containing extraluminal gas was less than the proportion containing heterogeneity (56% vs 94%, P = 0.04). In the group with necrosis without pus, bacterial growth was present in cultures of the surgical specimens from 12/14 (86%) patients; while in the group with necrosis and pus, bacterial growth occurred in 10/12 (83%) patients. All these patients were on high-dose broad-spectrum antibiotics at the time of operation. Among the necrotic collections without pus, there were gram positive and gram negative infections in 50% and 14%, respectively, and mixed infections in 21%. On the other hand, among the necrotic collections with pus, there were gram positive and negative infections in 25% and 33%, respectively, and mixed infections in 25%. Table 3 shows the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, and positive and negative likelihood ratios of fluid heterogeneity and the presence of extraluminal gas on CT in predicting the presence of pus in peripancreatic collections.

| Heterogeneity | Presence of air | Both | |

| Sensitivity (%) | 93.8 | 47.3 | 47.4 |

| Specificity (%) | 52.0 | 84.0 | 92.0 |

| Positive predictive value (%) | 55.5 | 69.2 | 81.8 |

| Negative predictive value (%) | 92.9 | 67.7 | 23.3 |

| Positive likelihood ratio | 1.9 | 2.9 | 5.9 |

| Negative likelihood ratio | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

Earlier studies have demonstrated good correlation between CECT and operative exploration in diagnosing pancreatic necrosis in patients with AP[5-8]. The CECT feature that characterizes pancreatic necrosis most reliably is lack of enhancement of pancreatic parenchymal tissue[9]. In contrast, no specific CECT features that can differentiate peripancreatic necrosis from peripancreatic fluid without necrosis, especially early after the onset of pancreatitis, have been reported so far. MRI has been reported to be a more powerful tool for detecting necrotic debris within peripancreatic collections after acute pancreatitis[10], however, MRI is substantially more expensive than CECT and can be difficult to perform in the very ill patient, and requires radiologic experience and expertise in its interpretation. These considerations regarding MRI vs CECT increase the likelihood of the utility of CECT in the assessment of patients worldwide with severe acute pancreatitis for years to come. In this study, we evaluated the correlation between CECT findings of peripancreatic collections with objective findings at operative exploration in order to assess the ability of CECT to predict the nature of these collections. Such differentiation would be important from the standpoint of better clinical decision-making, and thereby, possibly altering the treatment of these collections.

Importantly in this study, we specifically avoided the term “peripancreatic fluid collection” as was adapted by the Atlanta Classification. This term, in our opinion, has stifled progress in this field, led to controversy in the discussion of acute fluid collections vs peripancreatic necrosis, and has led to unnecessary controversy as well as confusion as to the appropriate use and misuse of purely drainage procedures (radiologic, endoscopic, or operative) vs procedures allowing a true necrosectomy. Therefore, we use the term peripancreatic “collection” rather than peripancreatic “fluid collection”, because early in the course of necrotizing pancreatitis, some (perhaps most) pancreatic collections are composed primarily of necrosis without substantial fluid components, thereby differentiating them from acute fluid collections that lack necrosis. This study was designed, in part, to see if CT would be able to differentiate areas of necrosis (with or without a fluid component) from collections of fluid without necrosis.

We found that CT had a false positive rate (peripancreatic collections seen on CT but not found at operation) of 17% (11/65) and a false negative rate (collections found at operation but not seen on CT) of 17% (9/54). The false positive and false negative collections on CT were excluded from the comparative analysis. Operative findings and histologic evidence confirmed that over 90% of the peripancreatic collections detected on CECT in patients with necrotizing pancreatitis undergoing operative exploration/necrosectomy contained necrosis. In the current study, we found all the CT parameters (heterogeneity, attenuation, wall perceptibility, wall enhancement, wall irregularity, and presence of extraluminal gas) to be similar in the groups with necrosis without pus and fluid without necrosis. In contrast, heterogeneity and presence of extraluminal gas were significantly more common in the group with necrosis and pus, compared to the collections without necrosis. All other parameters were similar. Therefore, CT did not have any specific feature that would reliably detect the presence of necrosis within the peripancreatic collections. The presence of irregularity of the wall of the collection was more common in those with necrosis (88% and 71% with and without pus, respectively) but not enough to reliably differentiate necrotic collections from fluid collections, 25% of which had an irregular wall.

If we consider the groups with necrosis with and without pus, the presence of heterogeneity on CT was seen in a significantly greater proportion in the former group with a sensitivity and positive likelihood ratio of detecting pus in the collection of 94% and 1.9%, respectively. The presence of extraluminal gas within fluid collections is well-recognized as a marker of infection in the absence of a history of prior endoscopic, radiologic, or operative intubation. In the current study, as expected, internal air was seen in a significantly greater proportion of collections with pus (indeed no fluid collection without necrosis had gas within it), although significantly less than those with heterogeneity (P = 0.04). When both heterogeneity and the presence of extraluminal gas were combined, then the positive likelihood ratio increased substantially to 5.9, and the absence of both reliably excluded the presence of pus (specificity 92%). From these observations, it is clear that heterogeneity and presence of extraluminal gas in the peripancreatic collections in a patient with severe acute pancreatitis can suggest the presence of pus, i.e. purulent infection. The characteristics of the progression of infection in necrotic tissue is a dynamic process, and pus formation tends to occur in the later stages of the disease. In this study, bacterial growth occurred in 86% patients with a peripancreatic collection containing necrosis but no obvious pus. None of the CT features could, therefore, detect the presence of infection in this group of collections, i.e. infected necrosis without pus.

To our knowledge, this analysis is among the very few studies in the literature that have assessed the direct correlation between CECT and operative findings in the diagnosis and characterization of peripancreatic collections in the presence of severe acute pancreatitis. We used operative exploration as the gold standard to detect the presence of necrosis within these collections which was confirmed histologically. The operative data and the CECT findings were interpreted and analyzed by a single, blinded surgeon and radiologist, respectively. This approach helped to eliminate the chance of bias in the interpretations. This study, however, has a few limitations. First, this is a retrospective study, and the number of collections in the group with fluid without necrosis was only 4. This small number of fluid collections could have potentially skewed the CECT findings towards an inability to detect necrosis within the collections. Moreover, the CECT scans were performed between 1995 and 2001, when older generation machines with thick sections were used. The use of modern, multidetector CECTs with thinner slice sections might increase the ability of CECT to detect the presence of infection in these collections without pus. Second, the gold standard for the presence of a collection was operative exploration. We believe that this method was most appropriate, because at operative exploration, the operative approach at our institution is to expose the entire pancreas and open all areas of the peripancreatic retroperitoneum to ensure complete necrosectomy. In addition, CECT serves as a roadmap for surgery, and all collections noted on CECT were specifically sought in the operating room. Finally, the patients we studied were a skewed population with necrotizing pancreatitis, all of whom required operative intervention and thus represent only patients with necrotizing pancreatitis.

In conclusion, this study shows that most of the peripancreatic collections seen on CECT in patients with severe acute pancreatitis who require operative intervention contain necrotic tissue. It appears that CECT has a somewhat limited role in differentiating the different types of collections into necrosis with pus, necrosis without pus, and fluid collections without necrosis. While heterogeneity of the collection can reliably suggest the presence of necrosis, and extraluminal gas defines the presence of infection in a collection with necrosis, no CECT feature could suggest the presence of infection in a necrotic collection without pus.

Earlier studies have demonstrated good correlation between contrast-enhanced computerized tomography (CECT) and operative exploration in diagnosing pancreatic necrosis in patients with acute pancreatitis. Studies evaluating CECT and operative correlation in the detection of peripancreatic necrosis and peripancreatic fluid collections are scarce. Vege et al suggested that peripancreatic necrosis may not be seen on CECT and that a normal enhancement of the pancreas does not necessarily rule out the presence of peripancreatic necrosis.

There are very few similar studies in the literature so far. In this study, the authors objectively correlated peripancreatic collections seen on CT with those actually seen at surgery. The use of surgery as a gold standard adds maximum value to this study.

This study shows that while heterogeneity of the collection can reliably suggest the presence of necrosis, and extraluminal gas can define the presence of infection in a collection with necrosis, no CECT feature can suggest the presence of infection in a necrotic collection without pus. However, since the authors’ sample size was not very large, the data could be validated in centers where a large volume of surgery is still performed for peripancreatic collections in patients with acute necrotizing pancreatitis.

The Authors reported an interesting study which correlates CECT and intraoperative findings in patients who required surgical drainage for peripancreatic collections following severe acute pancreatitis. The paper is clear, well written, the aim of the study is covered, the methodology of the study despite being retrospective is correct, the statistical analysis is well done and explores the most important topics and the discussion is complete.

| 1. | Banks PA, Freeman ML. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2379-2400. |

| 2. | Lenhart DK, Balthazar EJ. MDCT of acute mild (nonnecrotizing) pancreatitis: abdominal complications and fate of fluid collections. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:643-649. |

| 3. | Diculescu M, Ciocîrlan M, Ciocîrlan M, Stănescu D, Ciprut T, Marinescu T. Predictive factors for pseudocysts and peripancreatic collections in acute pancreatitis. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2005;14:129-134. |

| 4. | Kourtesis G, Wilson SE, Williams RA. The clinical significance of fluid collections in acute pancreatitis. Am Surg. 1990;56:796-799. |

| 5. | Kivisaari L, Somer K, Standertskjold-Nordenstam CG, Schroder T, Kivilaakso E, Lempinen M. A new method for the diagnosis of acute hemorrhagic-necrotizing pancreatitis using contrast-enhanced CT. Gastrointest Radiol. 1984;9:27-30. |

| 6. | Beger HG, Krautzberger W, Bittner R, Block S, Buchler . Results of surgical treatment of necrotizing pancreatitis. World J Surg. 1985;9:972-979. |

| 7. | Johnson CD, Stephens DH, Sarr MG. CT of acute pancreatitis: correlation between lack of contrast enhancement and pancreatic necrosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;156:93-95. |

| 8. | Block S, Maier W, Bittner R, Büchler M, Malfertheiner P, Beger HG. Identification of pancreas necrosis in severe acute pancreatitis: imaging procedures versus clinical staging. Gut. 1986;27:1035-1042. |

Peer reviewers: Massimo Falconi, MD, Chirurgia B, Department of Anesthesiological and Surgical Sciences Policlinico GB Rossi, Piazzale LA Scuro, 37134 Verona, Italy; Andrada Seicean, MD, PhD, Third Medical Clinic Cluj Napoca, University of Medicine and Pharmacy Cluj Napoca, Romania, 15, Closca Street, Cluj-Napoca 400039, Romania

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Ma WH