Published online Jun 14, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i22.2832

Revised: January 27, 2010

Accepted: February 4, 2010

Published online: June 14, 2010

The treatments for common bile duct (CBD) stones are being continually developed. Impaction of the lithotripsy basket during endoscopic removal of CBD stones was seen in 5.9% patients. We report the case of a 66-year-old woman who underwent surgery for the removal of an impacted biliary basket. She was admitted to our hospital with a complaint of right upper abdominal pain. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography revealed a CBD stone (20 mm × 15 mm). We diagnosed her with choledocholithiasis and performed endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography to remove the stone. However, unfortunately, the retrievable basket around the stone became impacted. An endotriptor along with forceps could not be used owing to the entrapment of the basket, and thus we performed urgent surgery. The basket containing the stone was removed through a longitudinal choledochotomy. The wires leading to the basket were cut, and the basket containing the stone was removed via the incision. A T-tube was inserted, and the choledochotomy was closed. The postoperative course was uneventful. In conclusion, if the diameter of a CBD stone is more than 20 mm, then the risk of basket impaction increases, and surgery may be necessary as the initial treatment of the CBD stone.

- Citation: Fukino N, Oida T, Kawasaki A, Mimatsu K, Kuboi Y, Kano H, Amano S. Impaction of a lithotripsy basket during endoscopic lithotomy of a common bile duct stone. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(22): 2832-2834

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i22/2832.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i22.2832

Endoscopic procedures for the removal of common bile duct (CBD) stones are well established[1-3], and include endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC), sphincterotomy, and basket or balloon extraction. However, endoscopic removal of large bile duct stones is difficult. The success or failure of lithotripsy depends on the size of the stone, number of stones, degree of jaundice, and presence or absence of gallbladder stone-induced cholecystitis. Here, we report the case of a patient with an impacted biliary basket.

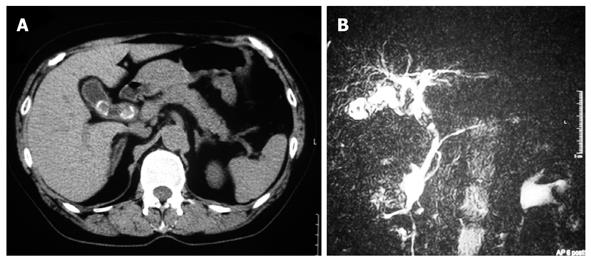

A 66-year-old woman with right upper abdominal pain was admitted to our hospital. Laboratory analysis on admission revealed elevated serum levels of the following biological parameters (the normal range for each parameter is in parentheses): alkaline phosphatase, 486 IU (109-335 IU); γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, 373 IU (12-48 IU); L-aspartate aminotransferase, 913 IU (12-32 IU); L-alanine aminotransferase, 449 IU (10-40 IU); total bilirubin, 2.3 mg/dL (0.2-1.4 mg/dL); and direct bilirubin, 1.3 mg/dL (0.0-0.3 mg/dL). The results of a complete blood count test and coagulation test were normal. The serum levels of tumor markers (carbohydrate antigen 19-9 and carcinoembryonic antigen) were within the normal ranges. Ultrasound examination and computed tomography revealed 2 stones in the gallbladder along with thickening of the gallbladder and a calcified stone in the CBD (Figure 1A). In addition, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography revealed a mass (20 mm × 15 mm in diameter) in the dilated CBD, which had a diameter of 20 mm (Figure 1B). We diagnosed the patient with choledocholithiasis-induced cholangitis and choledocholithiasis-induced cholecystitis. We planned endoscopic lithotripsy for the removal of the CBD stone as the initial treatment, followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

ERC revealed the CBD stone as a large defect filling the upper part of the CBD. We performed endoscopic stone extraction, because the biliary tract was dilated after the endoscopic lithotripsy. The metal spiral sheath advanced to the basket containing the entrapped stone. However, unfortunately, the retrievable basket around the stone became impacted in the middle of the CBD. It was impossible to crush the stone because it had hardened owing to calcification; in addition, it was impossible to shut the opening wire and to replace the basket catheter with an endotriptor.

Subsequently, because the basket was trapped, we performed urgent surgery involving cholecystectomy and choledochotomy, because, in our department, we did not have an extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy.

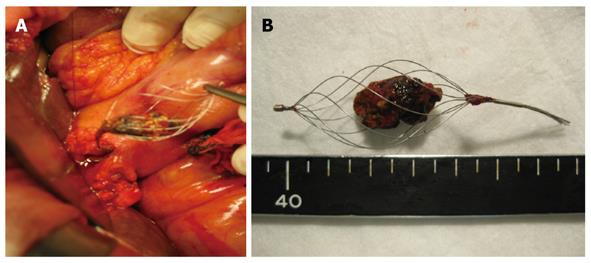

During the operation, cholecystectomy was performed, and the CBD was explored. The basket containing the stones was removed through a longitudinal choledochotomy (Figure 2). The wires leading to the basket were cut, and the basket containing the stone was removed via the incision. Intraoperative choledochoscopy revealed no residual stones or fragments. A T-tube was inserted, and the choledochotomy was closed. The postoperative course was uneventful and the patient is clinically healthy.

The treatment of CBD stones has advanced from choledochotomy to endoscopic management, with a success rate of over 90% for the latter[4,5]. The techniques used for the management of CBD stones are endoscopic sphincterotomy and endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation. However, the complications of endoscopic management are hemorrhage, pancreatitis, sepsis, cholangitis, and occasionally, impaction of the lithotriptor basket during the endoscopic removal of a CBD stone. The reported incidence of impaction of a basket with an entrapped stone was 5.9%[4,6,7]; however, because of the developments in the therapeutic techniques for CBD stones, this incidence has decreased to 0.8%[8].

The main factor responsible for impaction of the basket was reported to be the large size of the stone[4,6,7]. In the treatment of CBD stones with a diameter over 10-12 mm, a crush technique using endoscopic mechanical lithotripsy (EML) is employed, and the crushed stone is removed[9].

EML has been successfully used in 80%-90% of cases to crush CBD stones that were too large to be removed using conventional methods[10,11]. However, the management of very large stones with diameters of more than 25 mm, and of multiple stones in the ductus choledochus has failed[5]. In 4 studies that reported impaction of the basket, the average size of the stone was 17 mm (range, 13-20 mm)[4,7,12,13]. The success rate of EML for the treatment of large stones with diameters over 20 mm, was reported to be approximately 50%. However, the success rate is low if there are multiple stones and/or calcified stones. In our patient, the diameter of the stone was 20 mm: in addition, the stone was calcified and entrapped, and therefore could not be crushed and released in the lower part of the CBD. Impaction of the basket or CBD stone causes obstructive jaundice; furthermore, the likelihood of acute obstructive suppurative cholangitis, acute pancreatitis, and sepsis is great[14]. In the worst cases, failure of stone removal may result in the death of the patient. Garg et al[15] reported that stone size alone may not be an important factor that decides the success of EML; CBD dilatation with adequate working space between the stone and the wall of the CBD is also an important factor. In our patient, the size of the CBD stone was 20 mm and the CBD was dilated 20 mm, thus, there was no adequate space between the stone and the CBD wall to open the wire basket fully, and this may be one of the causes of failure of EML. In addition, cholecystitis with gallbladder stones may induce inflammatory changes in the CBD, leading to stiffness of the CBD, and, as a result, no adequate working space between the stone and the wall of the CBD.

In conclusion, we determined that if the size of CBD stone is over 20 mm in diameter and is calcified, the risk of an impacted basket is increased. In addition, if the CBD is not adequately dilated, there is insufficient space between the stone and the CBD wall to open the wire basket fully. In these cases, surgery may be selected as an initial treatment of CBD stones to prevent impaction of a basket.

| 2. | Safrany L. Endoscopic treatment of biliary-tract diseases. An international study. Lancet. 1978;2:983-985. |

| 3. | Cotton PB. Non-operative removal of bile duct stones by duodenoscopic sphincterotomy. Br J Surg. 1980;67:1-5. |

| 4. | Attila T, May GR, Kortan P. Nonsurgical management of an impacted mechanical lithotriptor with fractured traction wires: endoscopic intracorporeal electrohydraulic shock wave lithotripsy followed by extra-endoscopic mechanical lithotripsy. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22:699-702. |

| 5. | Fujita R, Yamamura M, Fujita Y. Combined endoscopic sphincterotomy and percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopic lithotripsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1988;34:91-94. |

| 6. | Schneider MU, Matek W, Bauer R, Domschke W. Mechanical lithotripsy of bile duct stones in 209 patients--effect of technical advances. Endoscopy. 1988;20:248-253. |

| 7. | Sauter G, Sackmann M, Holl J, Pauletzki J, Sauerbruch T, Paumgartner G. Dormia baskets impacted in the bile duct: release by extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy. Endoscopy. 1995;27:384-387. |

| 8. | Schreurs WH, Juttmann JR, Stuifbergen WN, Oostvogel HJ, van Vroonhoven TJ. Management of common bile duct stones: selective endoscopic retrograde cholangiography and endoscopic sphincterotomy: short- and long-term results. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1068-1072. |

| 10. | Van Dam J, Sivak MV Jr. Mechanical lithotripsy of large common bile duct stones. Cleve Clin J Med. 1993;60:38-42. |

| 11. | Hintze RE, Adler A, Veltzke W. Outcome of mechanical lithotripsy of bile duct stones in an unselected series of 704 patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 1996;43:473-476. |

| 12. | Merrett M, Desmond P. Removal of impacted endoscopic basket and stone from the common bile duct by extracorporeal shock waves. Endoscopy. 1990;22:92. |

| 14. | Nuehaus B, Safrany L. Complications of endoscopic sphinecterotomy and their treatment. Endoscopy. 1981;13:197-199. |

| 15. | Garg PK, Tandon RK, Ahuja V, Makharia GK, Batra Y. Predictors of unsuccessful mechanical lithotripsy and endoscopic clearance of large bile duct stones. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:601-605. |

Peer reviewer: Dr. Hyoung-Chul Oh, Assistant Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Chung-Ang University, College of Medicine, #65-207 Hanganro-3ga Yongsan-gu, Seoul 140757, South Korea

S- Editor Wang YR L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Lin YP