GENETIC MARKERS TO PREDICT DISEASE COURSE

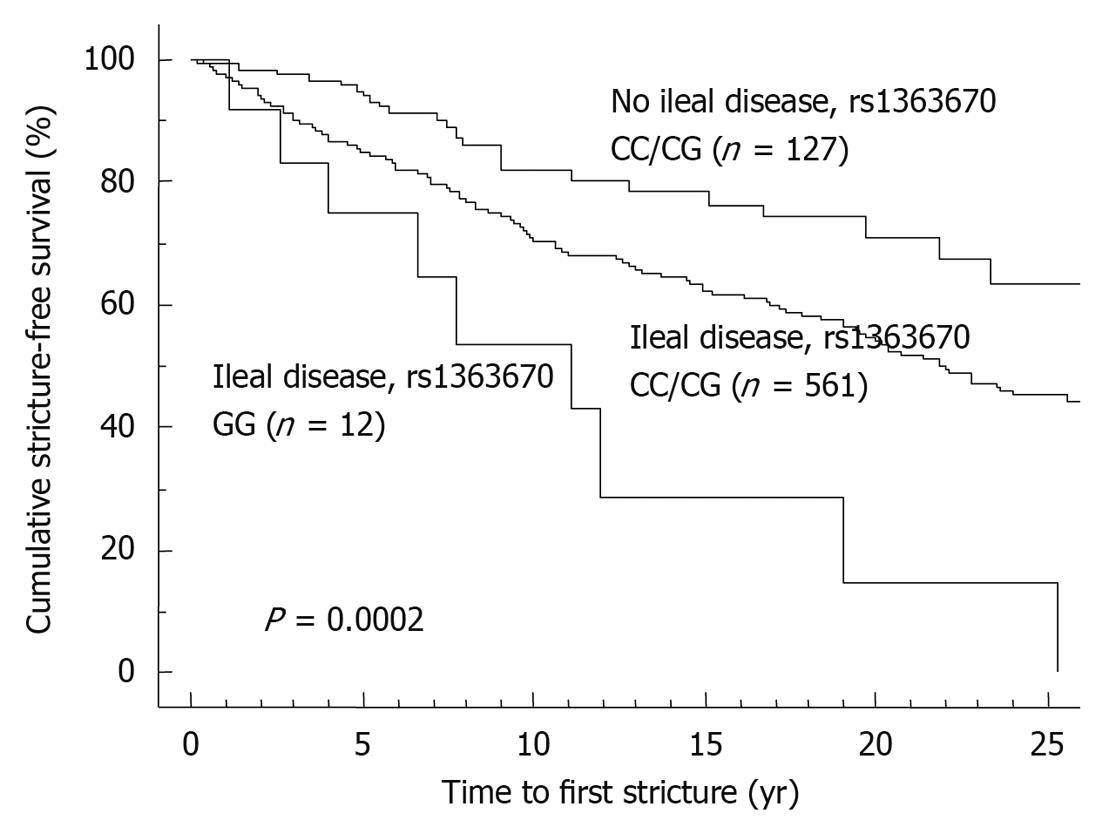

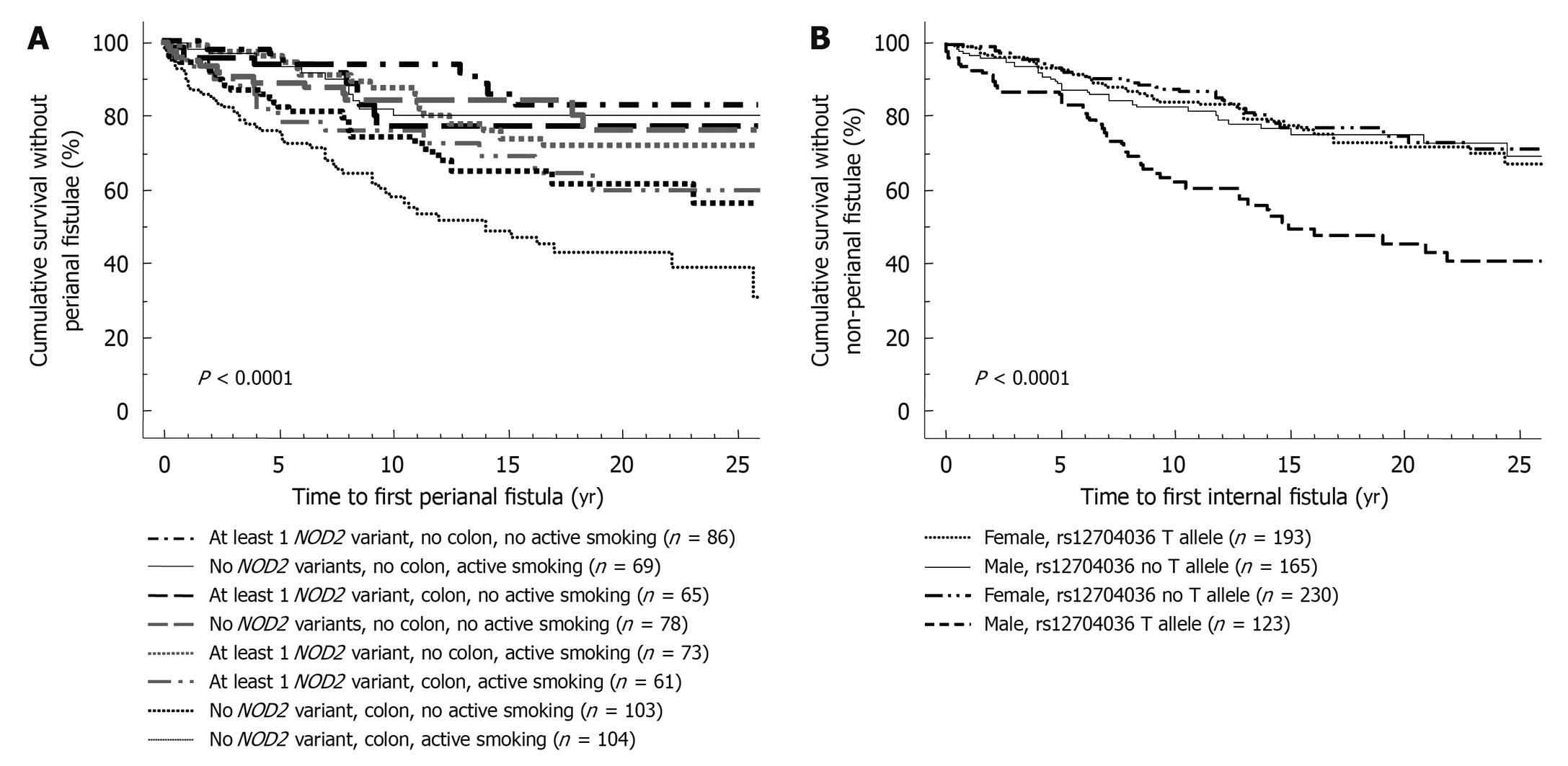

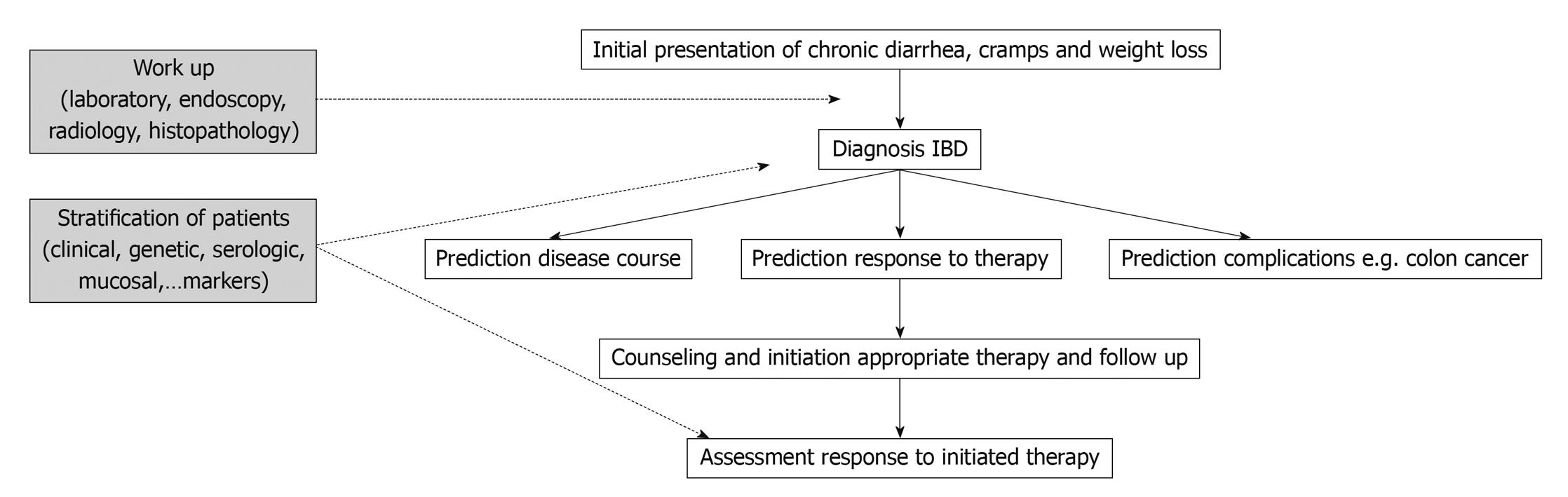

Compared to clinical parameters or serologic markers, genetic markers are more appealing for risk stratification as they are present long before the onset of the disease and before any environmental factor plays a role. In contrast to serologic factors, genetic factors are stable and are unaffected by disease flares. Moreover, as several studies have correlated microbial seroreactivity with genetic mutations in pattern recognition receptors, genetic markers may well prove to be superior[3,4]. Despite a large number of confirmed genetic variants in the susceptibility to CD and ulcerative colitis (UC), only very few have so far been proven to influence outcome. The presence of NOD2/CARD15 variants has been associated with a more rapid onset of stenosing small bowel disease and need for ileocecal resections[5-7]. In a Dutch tertiary multicentre cohort, Weersma et al[8] described a more severe disease phenotype, a higher need for surgery and a younger age at onset of CD with an increasing number of risk alleles and genotypes (NOD2, IBD5, DLG5, ATG16L1, IL23R). We studied whether the recently identified susceptibility genes for CD and their variants could improve stratification of patients, when applied together with other subphenotypes[9]. In a cohort of 875 CD patients with a median follow-up time of 14 years, homozygosity for the rs1363670 G-allele in a gene encoding a hypothetical protein near the IL12B gene was independently associated with a stricturing disease behavior with an odds ratio (OR) of 5.48 [95% confidence interval (CI), 1.60-18.83, P = 0.007] and furthermore with a shorter time to onset of these strictures (P = 0.01), and this was especially the case in patients with ileal involvement (P = 0.0002) (Figure 1). In the same cohort, male patients carrying a T-allele at rs12704036 T had the shortest time to development of non-perianal fistula. Presence of a C-allele at the CDKAL1 rs6908425 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and absence of NOD2 variants were both independently associated with development of perianal fistula, particularly when colonic involvement and active smoking were present (Figure 2). Despite their potential promise, genetic markers will most likely never fully predict evolution of disease, because of the incomplete penetrance, their modest to low frequency and the role of other (environmental) factors in shaping the disease. The place of genetic markers in predicting disease outcome more realistically lies in their integration with other molecular markers, clinical data and environmental triggers (Figure 3).

Figure 1 Time to onset of stricture formation in Crohn’s disease patients.

Figure 2 Stratification of patients with respect to development of perianal (A) or internal (B) penetrating disease.

Figure 3 Implementation of genetic markers in management of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

GENETIC MARKERS TO PREDICT THERAPY OUTCOME

Prediction of response to therapy is as accurate as prediction of disease course, and will become even more important as more therapeutic classes are being developed. The success of genetic markers in predicting outcome to CD or UC therapy has been limited, in contrast to other fields such as oncology, where molecular markers have demonstrated clinical utility in predicting response to chemotherapy. The response to cetuximab, a monoclonal antibody to epidermal growth factor receptor in metastatic colorectal cancer is influenced by the KRAS mutation status, as the benefit of cetuximab seems limited to patients with KRAS wild-type tumors[10]. Likewise, germline mutations may also correlate with clinical outcome to chemotherapy. A subanalysis of a large phase III study with bevacizumab (Avastin), a humanized monoclonal antibody to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), in metastatic pancreatic cancer, showed that overall survival and progression-free survival were influenced by SNPs in the tyrosine kinase domain of the VEGF receptor-1[11]. As in almost all human diseases necessitating medical therapy, a variable response is also observed for most drugs used in IBD. Between 20% and 30% of patients are refractory to any given medication despite optimal dose and duration. Besides the response, side effects and toxicity are also variable. These factors are of course not all explained by genetics. Disease duration, severity, behavior (inflammatory or stenosing) and concomitant therapies may all influence the response to a drug. Among the genetic factors, genetic variations in drug metabolizing enzymes and target proteins, and also heterogeneity in the patient’s genetic background will account for the variable response. Genetic polymorphisms in drug metabolizing enzymes will affect active drug concentrations and this, together with genetic polymorphisms of drug sensitivity (drug receptor genetic variants), will ultimately lead to heterogeneity in drug effects[12].

There are several reasons why pharmacogenetic research in IBD has witnessed only modest success: identifying molecular markers which influence the response to a drug is more difficult than, for instance, the study of genetic markers that influence toxicity. Side effects are usually easy to define and identify, in contrast to efficacy scores, which are often less well defined. In addition, and as already explained, treatment response in a heterogenic disease like IBD is influenced by many factors such as disease duration, behavior and severity. Finally, besides polymorphisms in specific drug metabolizing enzymes or target proteins, heterogeneity in the patient’s genetic background can also influence the response to treatment.

Since there are no or very little studies on genetic predictive factors for drugs such as methotrexate, cyclosporin, and tacrolimus, we focus in this overview on azathioprine and infliximab, on which most research has been conducted.

The only class of drugs where genetic testing for response prediction is useful and recommended are the thiopurine analogues. Azathioprine is metabolized by the enzyme thiopurine methyl transferase (TPMT), and the activity of this enzyme is under genetic control[13]. Mutations in the TPMT gene result in lower TPMT enzyme activity and this is associated with an increased risk for hematopoietic toxicity. In clinical practice, genotyping the most common TPMT variants or measuring TPMT enzyme activity can be carried out. Both techniques have advantages, and which technique is used is in part dependent on the availability. TPMT enzyme activity is measured in red blood cells with a radiochemical or high-performance liquid chromatography assay. The results can be influenced by blood transfusions but also other drugs may interfere with the TPMT enzyme activity (e.g. diuretics, 5-aminosalicylic acid). TPMT enzyme activity will identify patients with high TPMT activity that metabolize 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) to 6-methyl-MP and therefore may be resistant to treatment with thiopurine drugs. Genotyping is an easier method, but genotypes do not fully correlate with the enzyme activity, especially in the case of wild-type (some patients will have reduced TPMT activity) or heterozygous (some will have a normal TPMT activity) individuals[14-17]. Therefore, measuring TPMT enzyme activity will give a more accurate picture. In patients in whom TPMT testing is performed, azathioprine or 6-MP can be initiated at normal doses (2.5 and 1.5 mg/kg, respectively) in the case of a wild-type genotype or normal TPMT enzyme activity. When TPMT activity is intermediate or when patients are heterozygous for the common TPMT variants, a dose reduction of 50% is recommended. Finally, low or absent TPMT activity and/or compound heterozygous/homozygous mutant patients should not be initiated on azathioprine or 6-MP given the high risk of myelotoxicity. Socioeconomic analyses showed that TPMT phenotyping or genotyping was cost effective[18]. However, hematologic toxicity can also develop in patients with a normal TPMT activity and this is the reason why monitoring of blood counts and liver transaminases remains necessary in all patients, as long as they are taking this drug.

Apart from TPMT, mutations in the ITPA gene (inosine triphosphate pyrophosphatase) have also been studied with respect to azathioprine toxicity. ITPAse deficiency would result in the accumulation of the potentially toxic 6-thio-ITP. Although some studies reported an association between the ITPA 94C>A deficiency-associated allele and azathioprine toxicity, other studies could not confirm this[19-21].

Corticosteroids (CS) are effective as induction therapy in moderate to severe active UC and CD. The long term outcome data look less promising, however, as European as well as North American studies showed that 25%-30% of patients became steroid-dependent and 20% steroid-resistant within 1 year[22,23]. CS are potent inhibitors of T cell activation and cytokine secretion and mediate their antiinflammatory effect through binding the intracellular glucocorticoid (GC) receptor (GRα). A homodimer of 2 activated GRs is translocated to the nucleus and this complex then binds to specific DNA sequences and controls the expression of target genes [e.g. inhibition of the activator protein-1 (AP-1) gene and induction of the IκBα gene]. Several mechanisms have been proposed for the resistance to CS. Overexpression of the MDR1 (multidrug resistance) gene and subsequent elevated p-glycoprotein-mediated efflux of the drug was the first[24]. Altered functions of the GR and an excessive synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines have also been suggested. Steroid-resistant asthma patients do not respond to high doses of inhaled CS but develop Cushingoid side effects. In these patients reduced peripheral T lymphocyte GR binding affinity and abnormalities of GR-AP-1 interaction and increased expression of GRβ (a truncated splice variant of the normal isoform GRα) are observed. GRβ is unable to activate steroid-responsive genes. Honda et al[25] reported GRβ mRNA expression in 83% of the patients with steroid-resistant UC compared to only 9% in steroid-responsive patients, and 10% in healthy controls and chronic active CD patients. These results were confirmed in a recent study from Japan, where the authors looked at the frequency of GRα and β positive cells in colonic biopsies of GC-sensitive (n = 6) and GC-resistant (n = 8) UC patients[26]. They also found that there were significantly more GRβ-positive cells in the GC-resistant group than in the GC-sensitive and the control groups. Whereas GRα mRNA was expressed in all UC patients, GRβ mRNA was expressed in only 1 patient in the GC-sensitive group and in 7 patients in the GC-resistant group. Interestingly, the Foxp3+ cell count was also significantly higher in the GC-sensitive group.

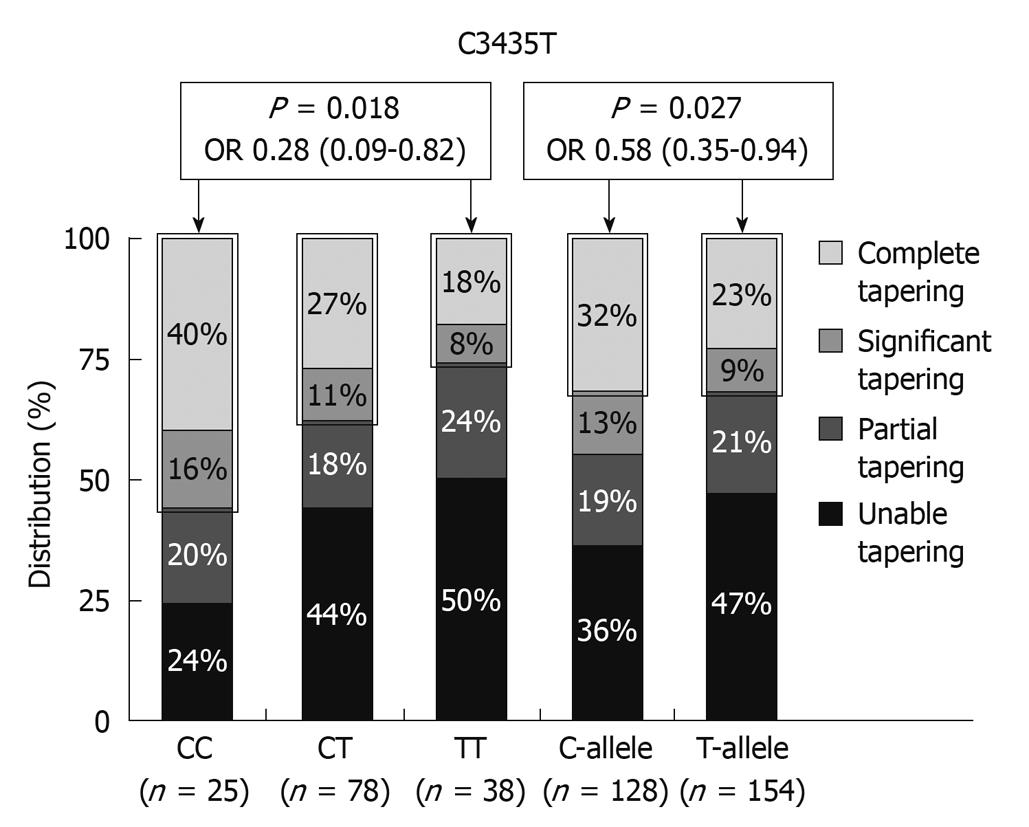

The MDR1 gene encodes for the drug efflux pump P-glycoprotein-170 (Pgp-170) and is expressed on the surface of lymphocytes and intestinal epithelial cells. Pgp and MDR expression were shown to be significantly higher in CD and UC patients requiring surgery due to failure of medical therapy[24]. MDR1 knockout mice spontaneously develop colitis and the MDR1 gene maps to the IBD susceptibility locus on chromosome 7 making it an excellent functional and positional candidate gene for susceptibility to IBD, and associations between C3435T and UC and G2677C/T and IBD have been described[27,28]. The MDR1 3435 TT genotype was especially associated with extensive UC. An association between steroid refractoriness and the 3435 TT genotype can therefore be the result of an extensive more severe disease phenotype in UC, but the TT genotype is associated with lower expression of MDR1 and Pgp170. Potocnik et al[29] reported an association between particular SNPs in introns 13 and 16 of the MDR1 gene and CS-refractory CD and UC. The C3435T SNP in exon 26 was, on the other hand, associated with significant or complete CS tapering in a cohort studied from Leuven (Figure 4)[30]. Several other associations with SNPs in the TNF (tumor necrosis factor) gene and the macrophage MIF (migration inhibitory factor) gene and CS dependency or sensitivity have also been reported[31,32]. What is clearly needed from reviewing the literature on this topic, are trials in patient cohorts treated with fixed doses of CS and followed with well defined response criteria. Instead of looking for candidate genes, mucosal expression studies looking at differences between responsive and resistant patients may pave the way.

Figure 4 Distribution (%) of C3435T MDR1 genotypes and alleles with respect to glucocorticosteroid tapering in patients under azathioprine maintenance therapy[27].

The use of monoclonal antibodies to TNF has greatly improved the quality of life of patients suffering from IBD but this therapy is expensive and not free from side effects. Although more than 75% of patients in general respond to infliximab or adalimumab, resistance is seen in a subset of patients. If early response could be accurately predicted, management could be optimized.

Early studies looking at genetic variants with respect to anti-TNF outcome focused logically on the TNF and TNF receptor pathway. Specific mutations in these genes were studied but results were either negative, or positive results could not be confirmed in larger cohorts[33-35]. Since nuclear factor-κB signaling and TNFα levels are lower in cells carrying a CD-associated CARD15 variant it was also hypothesized that patients carrying a mutation in the CARD15 gene might respond differently to treatment with a TNF blocking agent. No significant associations were found also here in 3 independent cohorts of patients, including the ACCENT study cohort[36,37].

One of the mechanisms of action of infliximab is induction of apoptosis of monocytes and T lymphocytes[38,39]. It was therefore postulated that failure to induce apoptosis would be associated with lack of efficacy. In a small pilot study from Amsterdam, 14 patients were given infliximab and underwent endoscopy and 99mTc-annexin V single photon emission computer tomography scanning before and 24 h after infliximab administration (5 mg/kg)[40]. There was a clear and significant uptake of annexin V in the responders, whereas no such uptake was seen in the non-responders. This study showed that molecular markers may assist in predicting the outcome of anti-TNF treatment. Therefore, as the efficacy of infliximab is partly the result of the ability to induce apoptosis of activated T lymphocytes, we analyzed the effect of polymorphisms in apoptotic genes on outcome[41]. In luminal CD, there was a response rate of 74.7% in patients with the Fas ligand -843 CC/CT genotype compared with a response rate of 38.1% in patients with the TT genotype (OR, 0.11; 95% CI: 0.08-0.56, P < 0.01). The poorer outcome in patients carrying FasL-843T could be overcome by concomitant use of azathioprine. Patients with the caspase-9 93 TT genotype all responded, in contrast with 66.7% of patients with the CC and CT genotypes (OR, 1.50; 95% CI: 1.34-1.68, P = 0.04).

Also polymorphisms in the Fcγreceptor 3A gene, binding the Fc portion of the immunoglobulin have been studied, building on the hypothesis that infliximab leads to complement activation and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. The Fcγ RIIIa receptor 158V allotype displays a higher affinity for IgG1 and an increased ADCC and influences the therapeutic response to rituximab, an anti-CD20 IgG1 used in the treatment of non-Hodgkin lymphomas[42]. Similarly, Louis et al[43] showed an association between FCGR3A-158 and biological and possibly clinical response to infliximab in CD. However, this association could not be confirmed in a subset of 344 patients from the large and well-defined ACCENT 1 cohort of 573 patients[44]. There was however again a trend towards a greater decrease in C-reactive protein after infliximab in V/V homozygotes as compared with V/F heterozygotes and F/F homozygotes (-79.4, -76.5, and -64.3%, respectively, at week 6, P = 0.085; one-tailed P = 0.043). This finding has no immediate clinical impact but may enhance the understanding of the complex mechanisms of action of anti-TNF agents in CD.

More recently, microarray technology has been applied to advance our understanding on the reasons for (non)response to this class of agents. This technology enables measurement of the expression of thousands of genes simultaneously. In order to identify predictive gene profiles, we studied mucosal gene expression using the genome-wide Affymetrix HGU133 Plus 2.0 arrays in infliximab-naive CD and UC patients[45]. By comparing pre-treatment colonic mucosal expression profiles of responders with non-responders, we found that expression of IL-13Rα2 separated IBD responders from non-responders with 100% sensitivity and 91.3% specificity. The interleukin receptor, IL-13Rα2 has raised a lot of interest lately because of its involvement in fibrogenesis. IL-13 is a critical regulator of a Th2 response and is the key cytokine in parasite immunity and in the generation of an allergic response. IL-13 can bind to IL-13Rα1 with low affinity, causing downstream STAT6 activation. Alternately, IL-13 together with TNF-α can induce IL-13Rα2 expression and IL-13 can bind it with high affinity. This interaction leads to activation of the TGF-β1 promoter 20. It has been shown in a mouse model of colitis, that the initial Th1 response subsides after 3 wk and is followed by an IL-23/IL-25 response with IL-17 and IL-13 production, TGFβ1 production and the onset of fibrosis. If IL-13 signaling through this receptor is blocked by administration of soluble IL-13Rα2-Fc, or by administration of IL-13Rα2-specific small interfering RNA, TGF-β1 is not produced and fibrosis does not occur. Therefore, IL13Rα1 deserves further study.

Finally, for drugs such as methotrexate, cyclosporin, and tacrolimus, which are used less often in IBD, no or very few studies on genetic predictive factors have been conducted.