Published online Mar 28, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i12.1533

Revised: December 19, 2009

Accepted: December 26, 2009

Published online: March 28, 2010

The surgical management of gallstone ileus is complex and potentially highly morbid. Initial management requires enterolithotomy and is generally followed by fistula resection at a later date. There have been reports of gallstone extraction using various endoscopic modalities to relieve the obstruction, however, to date, there has never been a published case of endoscopic stone extraction from the colon using electrohydraulic lithotripsy. In this report, we present the technique employed to successfully perform an electrohydraulic lithotripsy for removal of a large gallstone impacted in the sigmoid colon. A cavity was excavated in an obstructing 4.1 cm lamellated stone in the sigmoid colon using electrohydraulic lithotripsy. A screw stent retractor and stent extractor bored a larger lumen which allowed for guidewire advancement and stone fracture via serial pneumatic balloon dilatation. The stone fragments were removed. Electrohydraulic lithotripsy is a safe and effective method to treat colonic obstruction in the setting of gallstone ileus.

- Citation: Zielinski MD, Ferreira LE, Baron TH. Successful endoscopic treatment of colonic gallstone ileus using electrohydraulic lithotripsy. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(12): 1533-1536

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i12/1533.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i12.1533

Gallstone obstruction of the colon is a rare event[1]. The traditional approach has been an initial enterolithotomy followed by fistula resection as indicated[2]. Although this has been shown to be successful, endoscopic therapies offer a less invasive approach. Non-surgical treatment of gallstone(s) impacted in the colon has been described using extracorporeal lithotripsy, dormia baskets and polypectomy snares[3-6]. These techniques, while successful in situations where the gallstone is small enough to be endoscopically extracted or where it yields enough to be broken with less radical endoscopic methods, can be inadequate for management of large stones. We encountered a large calcified stone impacted in the sigmoid colon that required localized disintegration by use of intracolonic electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL).

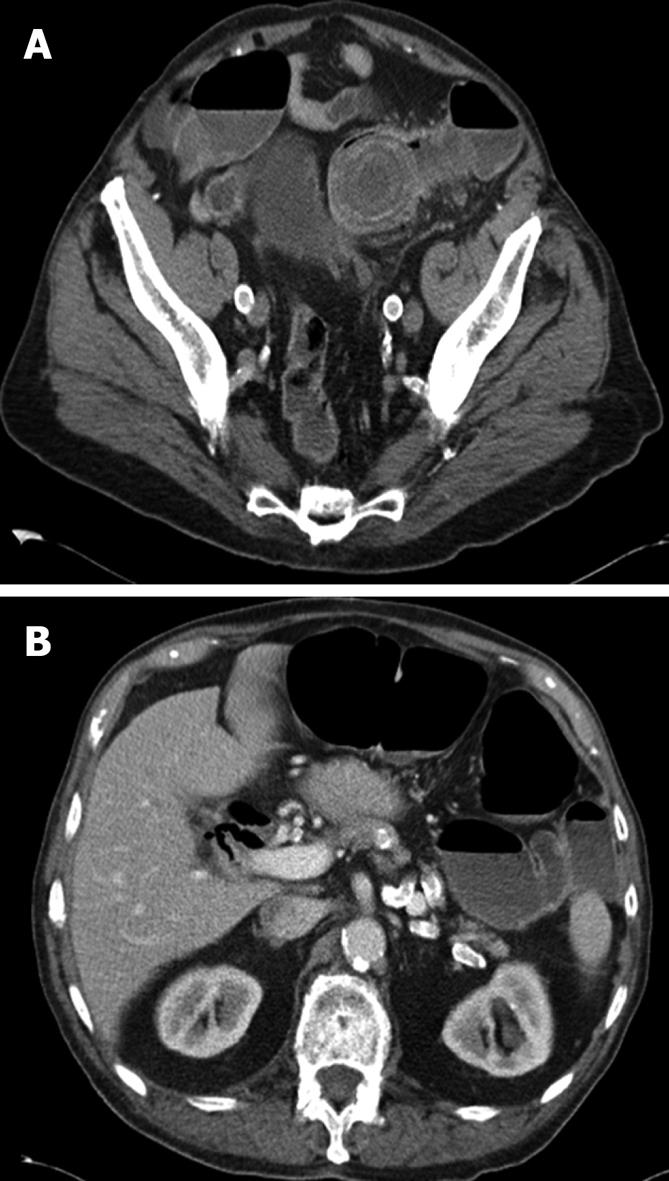

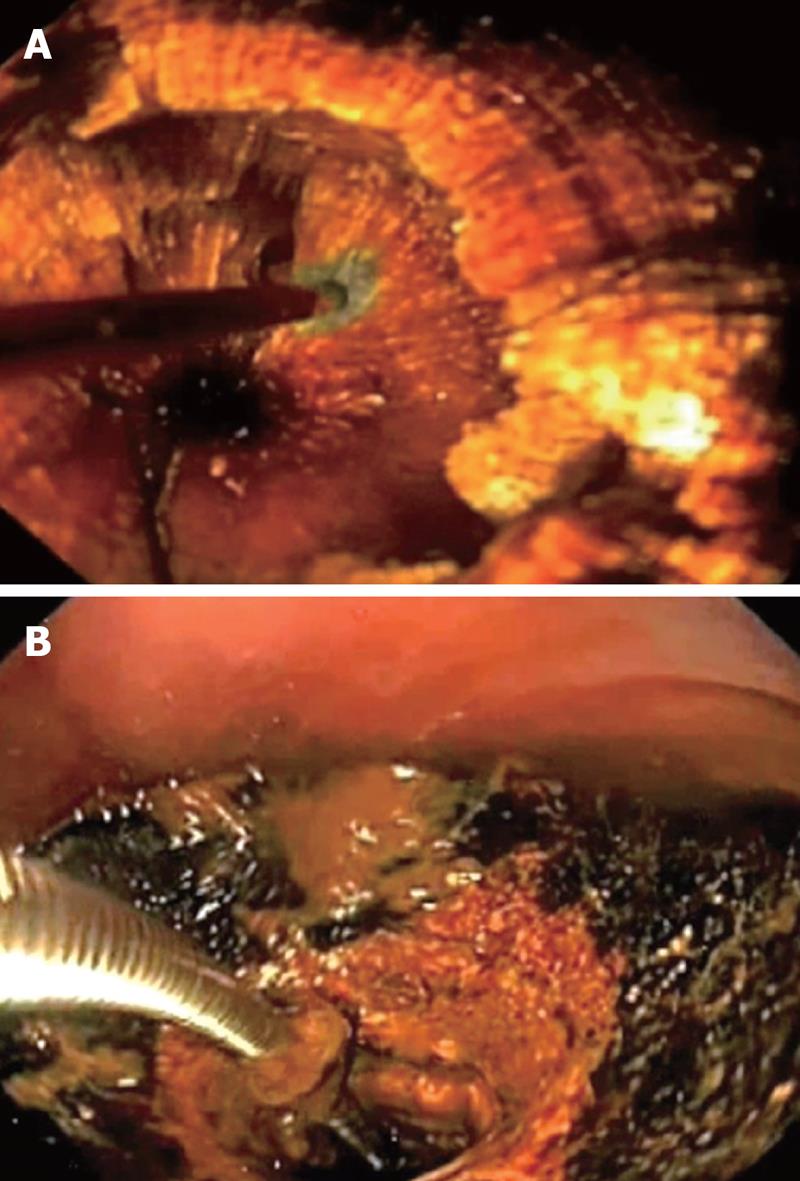

A 92-year-old man presented with a 5-d history of obstipation followed by nausea and vomiting. His abdomen was mildly distended with left lower quadrant tenderness. His past medical history was significant for diverticulosis, coronary artery disease, severe aortic stenosis and an attack of right upper quadrant pain with nausea and vomiting 6 mo previously. Computed tomography demonstrated dilated loops of small and large intestine proximal to a 4.1 cm lamellated stone impacted in the sigmoid colon (Figure 1A), in addition to a separate 3.8 cm stone within the gallbladder lumen. There was fistulous communication between the gallbladder fundus and the transverse colon with resultant pneumobilia (Figure 1B). Due to his advanced age and extensive comorbidities, endoscopic intervention was recommended. In the endoscopy suite, the patient was placed in the left lateral decubitus position. An Olympus gastroscope (Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA) was advanced transanally to the impacted piston-shaped stone which was found to be lodged within the distal sigmoid colon at an area of narrowing, likely from prior diverticulitis. A 1.9 French EHL probe (Northgate Research Inc., Arlington Heights, IL) was passed through the biopsy channel of the gastroscope. Continuous normal saline instillation was used to provide a medium for EHL. EHL was performed by applying shocks to the center of the impacted stone using the Northgate SD-100 EHL generator with shock delivery at a setting of 70 to 100 watts (Figure 2A). A total of nine EHL probes were required to excavate a cavity through the core of the stone after 2200 cumulative shocks. The shocks did not produce fragmentation but rather a “tunnel” through the stone. Due to poor visualization, when a small amount of blood was seen exiting from the proximal end of the tunnel it was assumed a complete lumen was created within the stone. A guidewire was advanced through the cavity into the proximal colon. A 7 French Soehendra screw stent retractor and a 10 French Soehendra screw stent extractor (Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, NC) were used to enlarge the proximal lumen (Figure 2B). This allowed passage of a dilating balloon to enable the stone to be fractured from within. Dilation using 18, 19 and 20 mm balloons inflated to maximum PSI was performed within the stone neolumen, causing it to fracture into four large pieces (Figure 3). These were retrieved using a Roth basket (US Endoscopy, Mentor, OH) and a large polypectomy snare. Concerns over the duration of the manipulation and resulting colonic wall edema necessitated termination of the procedure after a colonic decompression tube was placed over a guidewire that extended to the descending colon. We were able to reconstruct the gallstone into its whole form, confirming that no potentially obstructing stone fragment was retained.

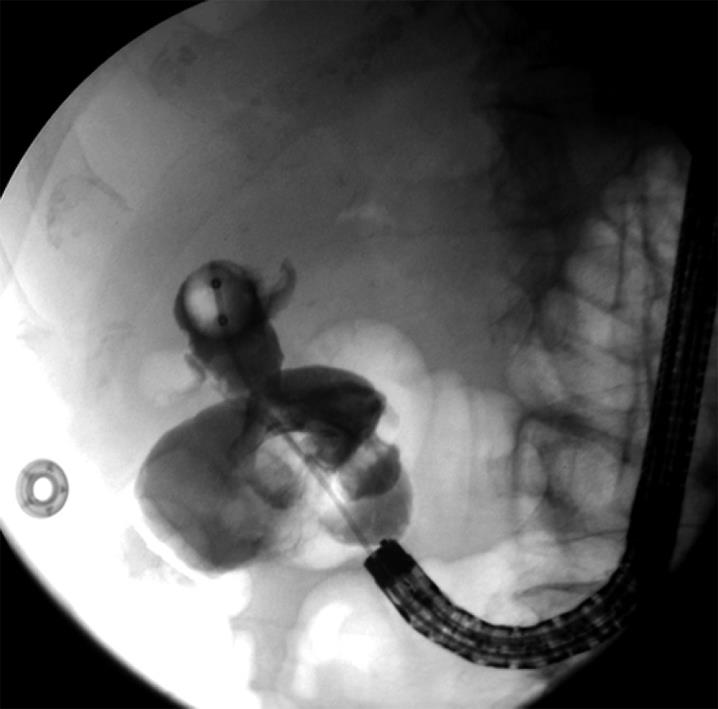

Due to concerns of biliary tract infection and recurrent gallstone ileus, an attempt at extraction of the existing gallstone within the gallbladder was attempted the following day. An Olympus IT gastroscope was advanced to the hepatic flexure where a large cholecystocolonic fistula was encountered. We advanced the endoscope through the fistula into the gallbladder fundus but no gallstone was encountered. Fluoroscopy and contrast injection through a biliary occlusion balloon (Olympus America, Inc.) demonstrated a stricture within the fundus and a large filling defect wedged within the gallbladder infundibulum consistent with the known retained gallstone (Figure 4). The stricture prevented further endoscopic manipulation. Therefore, the patient underwent resection of the fistulous tract with en bloc cholecystectomy and segmental colonic resection via a right subcostal incision. This confirmed a 4 cm long cholecystocolonic fistula from the fundus of the gallbladder to the hepatic flexure. The known retained stone plus an additional 1 cm stone were found within the infundibulum. This was walled off from the fundus due to the stricture. An intra-operative cholangiogram confirmed patency of the patient’s biliary system without evidence of bile leak.

The patient recovered from a gastrointestinal standpoint without any complications related to the endoscopic procedures. Post-operatively, he developed decompensated congestive heart failure and pulmonary hypertension in addition to atrial fibrillation. He was discharged on post-operative day 25 after optimization of his cardiac function. The patient died at home 12 mo later secondary to aspiration pneumonia.

Gallstone ileus is a rare clinical entity accounting for 1% to 3% of intestinal obstruction and is more common in the elderly population[1]. Gallstones most commonly impact in the terminal ileum (61%) followed by the jejunum (16%), stomach (14%), and large intestine (4%) at the rectosigmoid junction. The classic signs on imaging studies include dilated bowel and pneumobilia. Aberrantly located gallstones are present in about 50% of patients[7]. Initial surgical enterolithotomy is the traditional treatment and this allows for relief of the obstruction in the short term. Fistula resection can be safely performed during a second surgical procedure if indicated[2]. As this condition is predominantly encountered in an elderly population with a high incidence of comorbid conditions, the complication and mortality rates of surgical treatment are substantial[1,2]. Endoscopically accessible impacted gallstones are amenable to less invasive alternative therapeutic options including EHL, extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, intracorporal laser lithotripsy and endoscopic mechanical lithotripsy for fragmentation. To date, there have been a few case reports of the successful use of EHL in patients with gallstones impacted within the stomach and small intestine, but to our knowledge, this is the first report of the successful and safe use of EHL to remove an impacted gallstone within the sigmoid colon[8-12]. The EHL technique allows for fragmentation of large, calcified stones that would not otherwise be amenable to other endoscopic modalities. Advanced endoscopic skills, in addition to the proper equipment, are necessary as the technique has the potential to be long and complicated, but can ultimately be successful.

The patient’s retained gallstone posed a high risk for biliary infection and recurrent gallstone ileus and therefore the patient underwent an attempt at endoscopic retrieval of the retained gallstone within the gallbladder. Due to the stricture at the infundibulum, we were unable to manage this without operative intervention. However, the endoscopic extraction of the obstructing gallstone was able to eliminate an enterolithotomy procedure. This simplified his initial management and allowed him to undergo fistula resection under optimal conditions.

In summary, we present our technique for the first reported use of EHL to endoscopically extract an impacted gallstone within the lumen of the colon and believe that this is a safe and effective method to treat colonic obstruction in the setting of gallstone ileus.

| 1. | Reisner RM, Cohen JR. Gallstone ileus: a review of 1001 reported cases. Am Surg. 1994;60:441-446. |

| 2. | Ayantunde AA, Agrawal A. Gallstone ileus: diagnosis and management. World J Surg. 2007;31:1292-1297. |

| 3. | Meyenberger C, Michel C, Metzger U, Koelz HR. Gallstone ileus treated by extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:508-511. |

| 4. | Garcia-López S, Sebastián JJ, Uribarrena R, Solanilla P, Artigas JM. Successful endoscopic relief of large bowel obstruction in a case of a sigmoid colon gallstone ileus. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;24:291-292. |

| 5. | Zaretzky B, Kodsi BE, Iswara K. Colonoscopic diagnosis and relief of large bowel obstruction caused by impacted gallstone. Gastrointest Endosc. 1977;23:210-211. |

| 6. | Roberts SR, Chang C, Chapman T, Koontz PG Jr, Early GL. Colonoscopic removal of a gallstone obstructing the sigmoid colon. J Tenn Med Assoc. 1990;83:18-19. |

| 7. | Rigler LG, Borman CN, Noble JF. Gallstone obstruction: pathogenesis and Roentgen manifestation. JAMA. 1941;117:1753-1759. |

| 8. | Apel D, Jakobs R, Benz C, Martin WR, Riemann JF. Electrohydraulic lithotripsy treatment of gallstone after disimpaction of the stone from the duodenal bulb (Bouveret's syndrome). Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;31:876-879. |

| 9. | Bourke MJ, Schneider DM, Haber GB. Electrohydraulic lithotripsy of a gallstone causing gallstone ileus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:521-523. |

| 10. | Moriai T, Hasegawa T, Fuzita M, Kimura A, Tani T, Makino I. Successful removal of massive intragastric gallstones by endoscopic electrohydraulic lithotripsy and mechanical lithotripsy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:627-629. |

| 11. | Huebner ES, DuBois S, Lee SD, Saunders MD. Successful endoscopic treatment of Bouveret‘s syndrome with intracorporeal electrohydraulic lithotripsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:183-184; discussion 184. |

| 12. | Ferreira LE, Topazian MD, Baron TH. Bouveret’s syndrome: diagnosis and endoscopic treatment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:e15. |

Peer reviewer: Sri P Misra, Professor, Gastroenterology, Moti Lal Nehru Medical College, Allahabad 211001, India

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Ma WH