Published online Mar 28, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i12.1465

Revised: December 19, 2009

Accepted: December 26, 2009

Published online: March 28, 2010

AIM: To investigate the role of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-like gene (PDGFRL) in the anti-cancer therapy for colorectal cancers (CRC).

METHODS: PDGFRL mRNA and protein levels were measured by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and immunohistochemistry in CRC and colorectal normal tissues. PDGFRL prokaryotic expression vector was carried out in Escherichia coli (E. coli), and purified by immobilized metal affinity chromatography. The effect of PDGFRL protein on CRC HCT-116 cells was detected by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazolyl-2)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), clone counting, cell cycle, and wound healing assay.

RESULTS: Both RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry showed that the expression of PDGFRL in colorectal normal tissues was higher than in cancer tissues. Recombinant pET22b-PDGFRL prokaryotic expression vector was successfully expressed in E. coli, and the target protein was expressed in the form of inclusion bodies. After purification and refolding, recombinant human PDGFRL (rhPDGFRL) could efficiently inhibit the proliferation and invasion of CRC HCT-116 cells detected by MTT, clone counting and wound healing assay. Moreover, rhPDGFRL arrested HCT-116 cell cycling at the G0/G1 phase.

CONCLUSION: PDGFRL is a potential gene for application in the anti-cancer therapy for CRC.

- Citation: Guo FJ, Zhang WJ, Li YL, Liu Y, Li YH, Huang J, Wang JJ, Xie PL, Li GC. Expression and functional characterization of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-like gene. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(12): 1465-1472

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i12/1465.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i12.1465

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common malignant tumors in the world. It is estimated that 783 000 new cases are diagnosed each year, and the number has increased rapidly since 1975[1]. CRC is the third most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer related mortality in the Western world. The incidence of CRC in China has increased rapidly over the past few decades[2]. The molecular mechanism of carcinogenesis and development of CRC is still not fully understood.

Tumor suppressor genes are genes that can slow down cell division, repair DNA errors, and tell cells when to die (a process known as apoptosis or programmed cell death). When tumor suppressor genes do not work properly, cells can grow out of control, leading to cancer. About 30 tumor suppressor genes have been identified, including p53, BRCA1, BRCA2, APC, RB1, and platelet-derived growth factor receptor-like gene (PDGFRL). Tumor suppressor genes cause cancers when they are inactivated, and encode proteins that normally serve as a brake on cell growth. When such genes are mutated, the brake may be lifted, resulting in the runaway cell growth known as cancer. Gain of oncogene function associated with loss of tumor suppressors is now widely accepted as a hallmark of cancer initiation and progression[3].

PDGFRL is located in chromosome 8p21.3-8p22, which is commonly deleted in sporadic hepatocellular carcinoma, CRC, breast cancer, and non-small cell lung cancers[4,5]. While its precise biological function is not known, PDGFRL encodes a 375aa product with significant sequence similarity to the ligand-binding domain of platelet-derived growth factor receptor β. Mutations in PDGFRL have been found in individual cancer samples[6-9]. An in-depth study using micro-cell-mediated chromosome transfer found that PDGFRL expression is decreased in the majority of breast cancer cells[10]. Recently, PDGFRL is identified to play a central role in the tumor suppressor network by adopting a network perspective[11]. Furthermore, PDGFRL was found to be involved in the suppression of the tumor metastatic phenotype as a strong candidate gene[12].

To further identify new genes involved in the pathogenesis of CRC, we analyzed the expression of PDGFRL in CRC tissues and normal tissues by both reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and immunohistochemistry, and found that PDGFRL was expressed at higher levels in normal tissues than in CRC tissues. We constructed pET22b-PDGFRL recombinant prokaryotic expression vector before expression and purification of the PDGFRL recombinant protein were completed. The biological features of protein were identified to inhibit the proliferation and invasion of CRC HCT-116 cells by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazolyl-2)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), clone counting, and wound healing assay. In addition, rhPDGFRL arrested HCT-116 cell cycling at the G0/G1 phase.

HCT-116 CRC cells and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were maintained by our lab and cultured in Dulbecco-modified Eagle medium (DMEM; Gibco) supplemented with 10% bovine calf serum (BCS) (Gibco). Cells were maintained at 37°C in an atmosphere of humidified air with 50 mL/L CO2.

Fifteen samples of CRC tissues and paired non-cancerous tissues (5 cm away from tumor) were obtained from the First Hospital of Changsha. Written consent was obtained from the patients, who agreed with the collection of tissue samples. The resected tissue samples were immediately cut into small pieces, and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen until use. All tumor tissue and paired non-cancerous tissue samples were pathologically confirmed.

RNA isolated from tissues and cells was reversibly transcribed and amplified using the RT-PCR System (Fermentas). Primer sequences used were sense 5′-CAAGAAGGTGAAGCCCAAAAT-3′ and antisense 5′-ACAAGGAACCACAGCCTGTCT-3′ for PDGFRL. A 587-bp Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) fragment was amplified as an internal control. For GAPDH, the forward primer 5′-AATCCCATCACCATCTTCCA-3′, and the reverse primer 5′-CCTGCTTCACCACCTTCTTG-3′ were used. After heating at 95°C for 1 min, PCRs were exposed to 30 cycles (GAPDH, 25 cycles) of 95°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 68°C for 1 min and 30 s with a final extension at 68°C for 10 min. The relative mRNA levels were normalized to that of GAPDH and the ratio of PDGFRL to GAPDH was calculated.

Paraffin sections were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated in graded alcohol. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubation in 3% hydrogen peroxide at reverse transcription (RT) for 10 min. Non-specific binding was blocked with phosphate buffered saline Tween-20 (PBST) containing 10% goat serum for 2 h at RT. PDGFRL antibody (Abcam) was added to each slide and incubated at 4°C overnight. Following three washes, slides were incubated with Envision (DAKO) for 40 min at RT. Diaminobenzidine was used as a chromogen. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted. Evaluation of immunohistochemical slides was done with a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope at × 100 magnification. The intensity of the staining was scored on a scale of 0 to 3+ where 0, 1, 2 and 3 represented no staining and weak, moderate or strong staining, respectively. The mean staining scores for tissues and the mean fold change in protein expression was calculated.

A DNA fragment encoding the gene PDGFRL was amplified by PCR using a sense primer, 5′-TGAGCCATGGATCAACACCTTCC-3′, and an anti-sense primer, 5′-AAGCTCGAGGGAAAACTCAACAGT-3′. The primers were introduced to an NcoI site (sense) and an XhoI site (anti-sense), respectively. The amplification was performed using 2 × pfu PCR MasterMix (MBI Fermantas) on an Eppendorf PCR instrument. The PCR products were purified by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and double digested and ligated into the expression vector pET22b(+), resulting in a pET22b-PDGFRL plasmid with the sequence encoding the gene PDGFRL. The constructed plasmid was transformed into competent Escherichia coli (E. coli). DH5α cells and the transformed strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth supplemented with ampicillin (100 μg/mL). All strains were incubated at 37°C with constant shaking (220 r/min). The recombinant was identified by PCR, double endonuclease digestion and DNA sequencing.

The recombinant plasmid pET22b-PDGFRL was transformed into E. coli expression strain BL21 (DE3) cells. One colony was picked up and was grown in 3 mL LB rich medium containing 100 mg/L ampicillin. After 8 h, 1 mL of the BL21 (DE3) cells were introduced into 100 mL of LB medium containing 100 mg/L ampicillin. Bacteria were grown at 37°C until an A600 of 0.6 was reached. Then, isopropyl-b-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was added to induce protein expression at 30°C. To check the expression of pET22b-PDGFRL, E. coli were induced at different final concentrations of IPTG such as 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5 and 2.0 mmol/L, and different time points such as 1, 2, 4 and 6 h, respectively. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4800 ×g for 30 min and the pellet was resuspended in 50 mmol/L sodium phosphate, 0.3 mol/L NaCl, pH 8.0. The resuspended cells were lysed by sonication. The cells after lysis were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

The protein was further purified by immobilized metal affinity chromatography (MagExtractor® His-tag protein purification kit, TOYOBO). The extracts were fractionated by gel filtration column chromatography (AKTA explorer 10S with HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 pg column, GE Healthcare) in 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 100 mmol/L NaCl. These fractionated extracts were desalinized using Slide-A-Lyzer® dialysis cassettes (Pierce Biotechnology), separated by denaturing SDS-PAGE, and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (CBB). Western blotting was performed using an anti -His antibody (Abcam)[13].

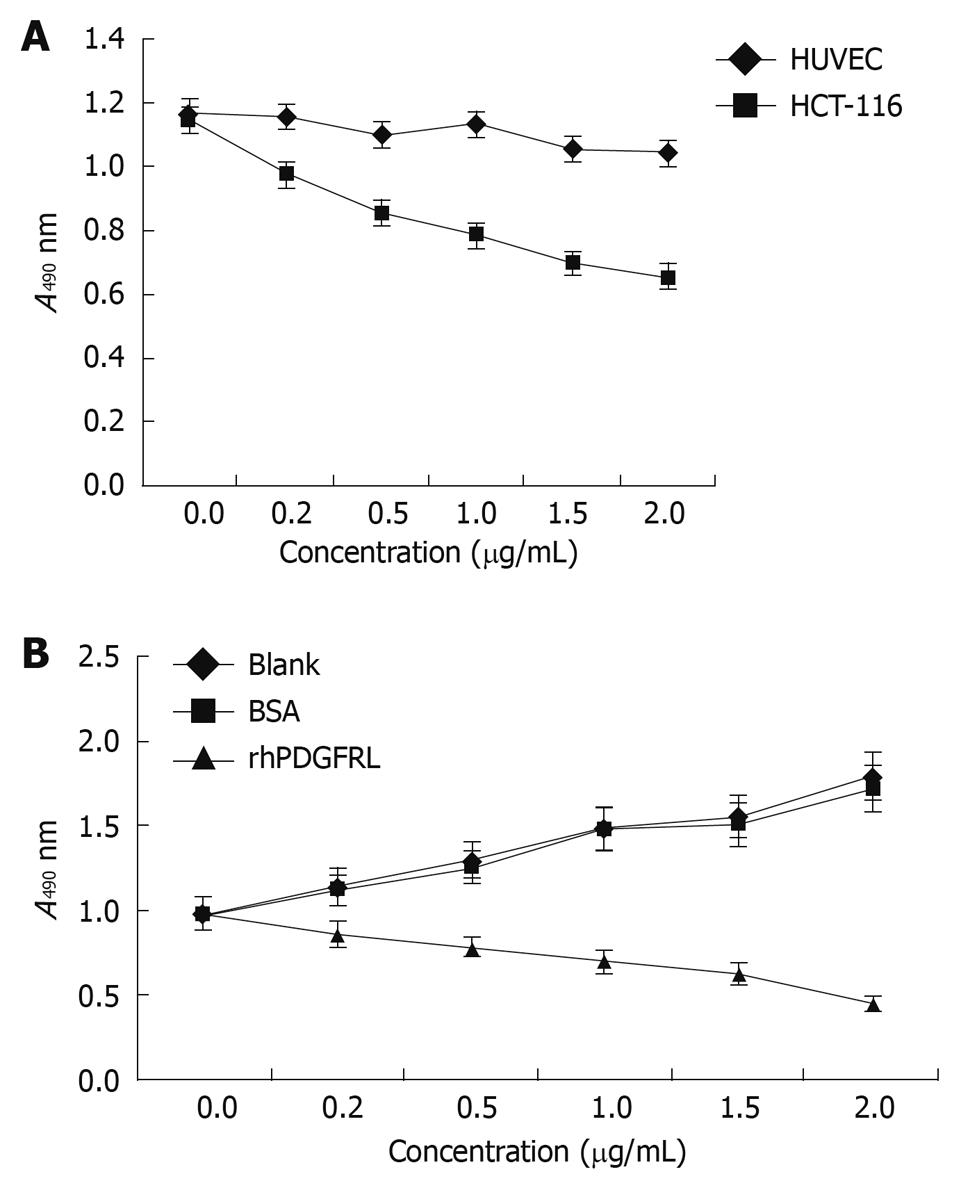

MTT assay was performed to measure cell viability and proliferation in external factors. The 3rd generation human HUVEC and HCT-116 cells were made into cell suspension with a density of 1 × 104/mL, which was inoculated into 96-well plates separately. The purified rhPDGFRL with different concentrations (0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5 and 2.0 μg/mL, suspended in DMEM plus 1% BCS) was added to HUVEC and HCT-116 cells. After two days, 5 mg/mL MTT was added into the wells and incubated at 37°C for 3 h. The supernatant was blotted and added with DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide). Absorbance of the dye was measured at a wavelength of 490 nm on a Microplate Reader. HCT-116 cells were then treated with rhPDGFRL or bovine serum albumin (BSA) (suspended in DMEM plus 1% BCS) and MTT assay was performed.

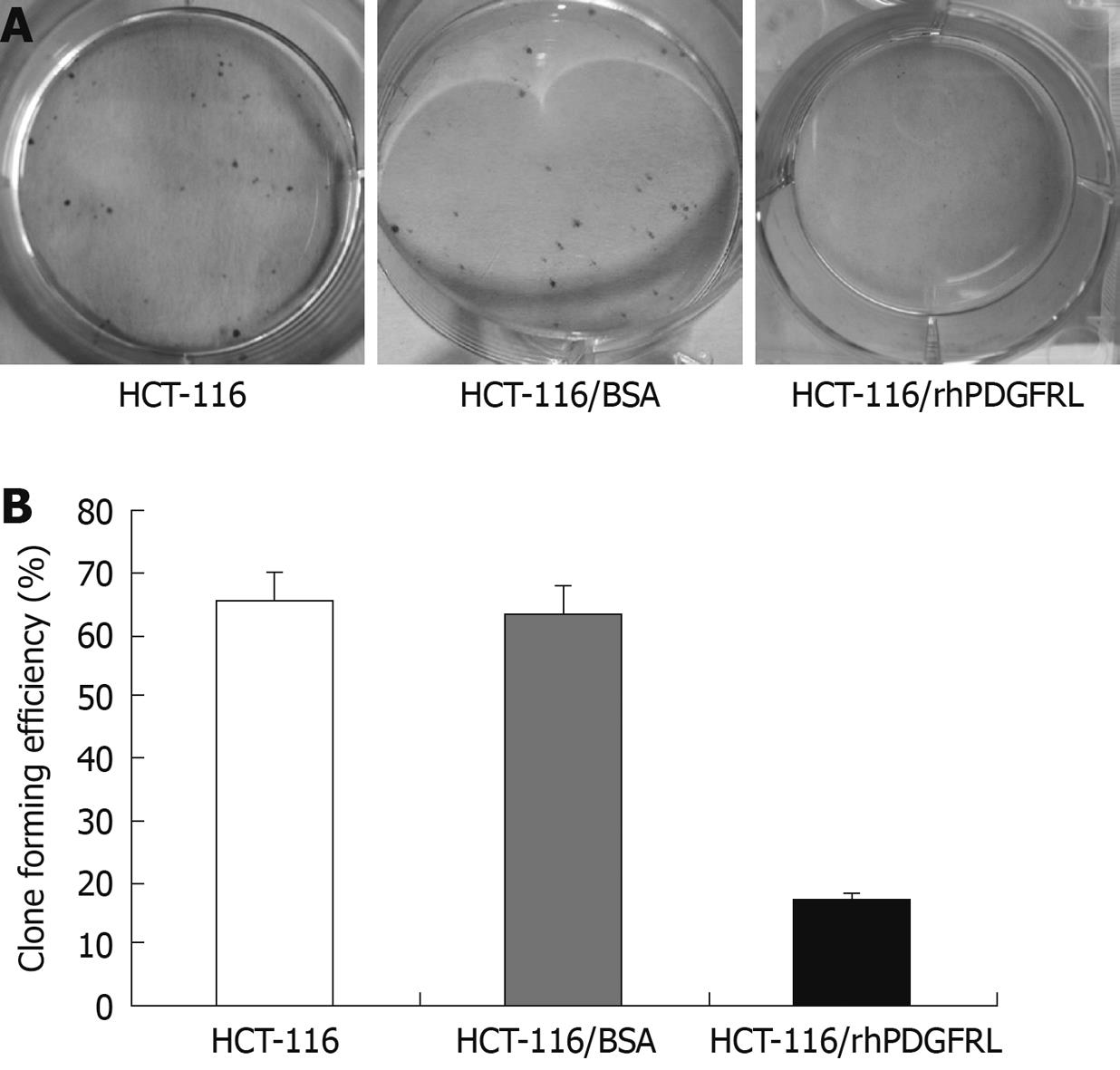

Crystal violet (CV) staining of cells and clone counting were used to measure cell proliferation. Dilute the HCT-116 cells into a 6-well plate separately and each pole contained 1000 cells. The rhPDGFRL or BSA (1.5 μg/mL) was added to HCT-116 cells. After 2 wk, 0.05% CV was added into the plates. The cells were fixed for 10 min with 4% Paraformaldehyde (PFA) and stained for 30 min with 0.05% CV. The plates were carefully rinsed in ddH2O until no color appeared. Clone forming efficiency for individual type of cells was calculated according to the number of colonies/number of inoculated cells × 100%.

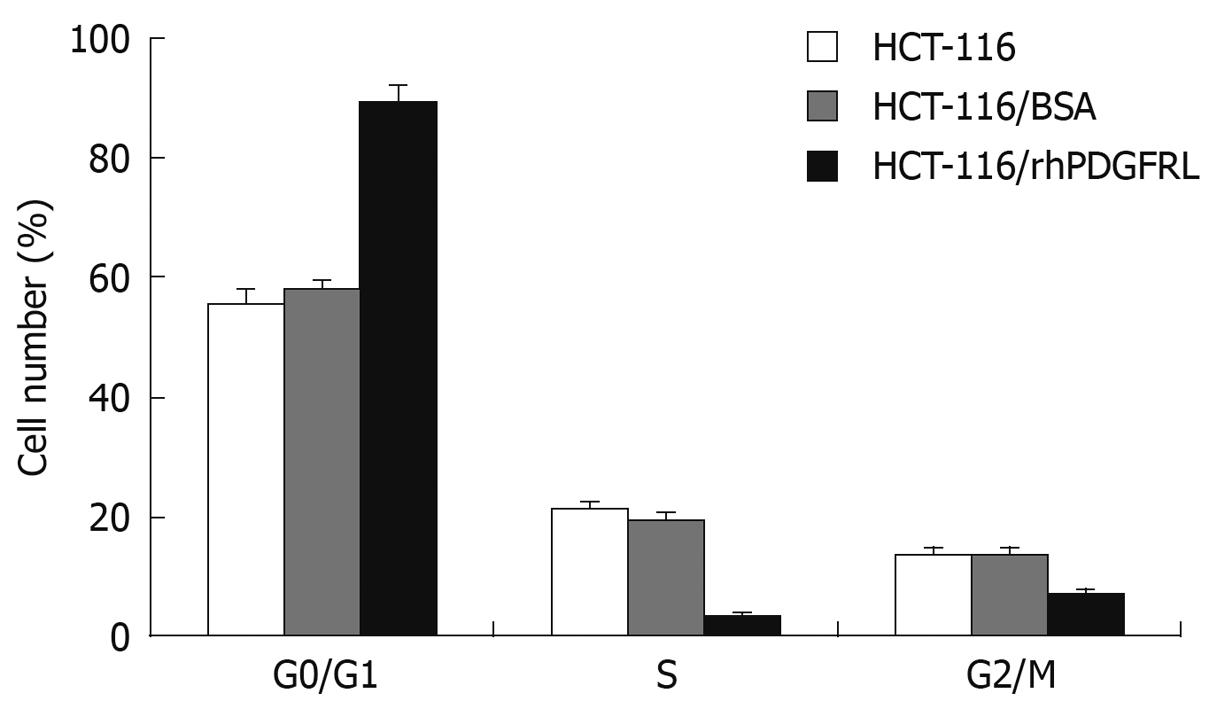

The impact of rhPDGFRL on the HCT-116 cell cycling was examined by flow cytometry. HCT-116 cells indicated were seeded into a 6-well plate at a density of 3.5 × 105 cell/well. Once the cells were grown at 70%-80% confluence, HCT-116 cells were treated with the rhPDGFRL or BSA (1.5 μg/mL). Cells were harvested at 48 h and resuspended in fixation fluid at a density of 106/mL, 1500 μL propidium iodide (PI) solution was added, and the cell cycle was detected by FACS Caliber (Becton Dickinson).

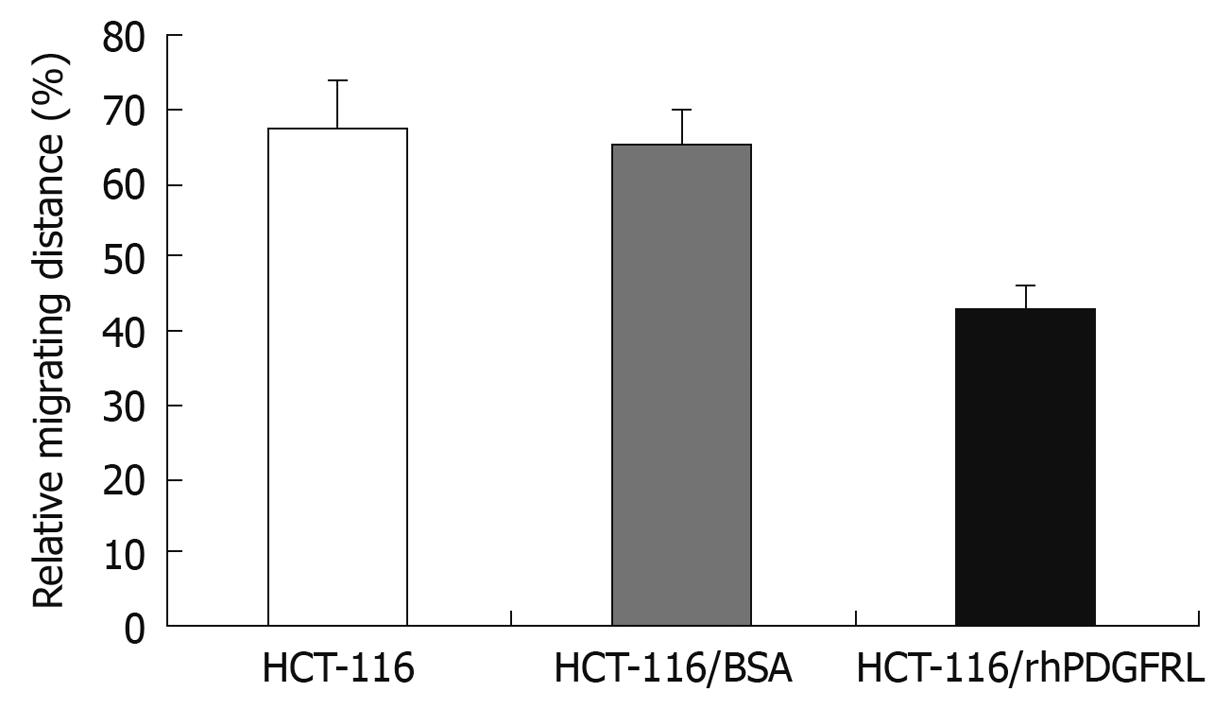

Wound healing assay was applied to measure cell invasion. HCT-116 cells indicated were seeded into a 6-well plate at a density of 3.5 × 105 cell/well. Once the cells were grown to a monolayer, a wound was made and the rhPDGFRL or BSA (1.5 μg/mL) was added to the HCT-116 cells. The distance of cell migration was calculated by subtracting the distance between the lesion edges at 48 h from the distance measured at 0 h. The relative migrating distance of cells was measured by the distance of cell migration/the distance measured at 0 h.

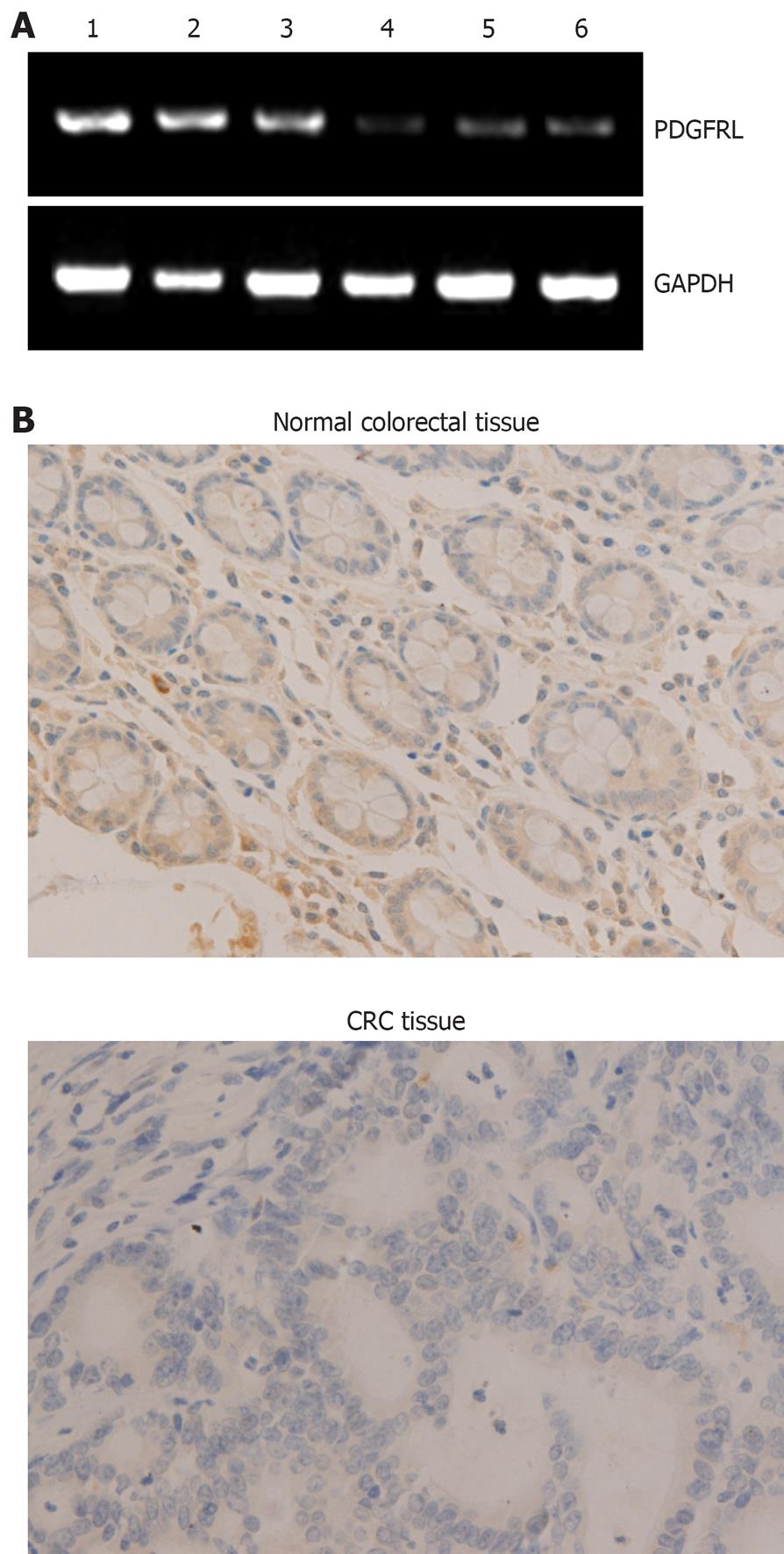

To verify PDGFRL in CRC and normal tissues, we did RT-PCR and immunohistochemical analysis in 15 human CRC and adjacent normal tissue samples. In RT-PCR analysis, mRNA levels in CRC tissues were lower than in normal tissues (Figure 1A). By immunohistochemical analysis, immunoreaction signal of PDGFRL in cancer tissues was weak compared with normal tissues (Figure 1B). Semi-quantitative analysis of mRNA and protein expression for PDGFRL was performed in CRC and adjacent normal tissue samples. The relative mRNA expression of PDGFRL in CRC tissues was 0.11, but the one in the adjacent normal tissues was 0.78. Likewise, the relative protein level of PDGFRL in adjacent normal tissues was 8.2, but the one in CRC tissues was only 1.3. Both RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry showed that the expression of PDGFRL in colorectal normal tissues was higher than in cancer tissues based on the identification of PDGFRL as a tumor suppressor.

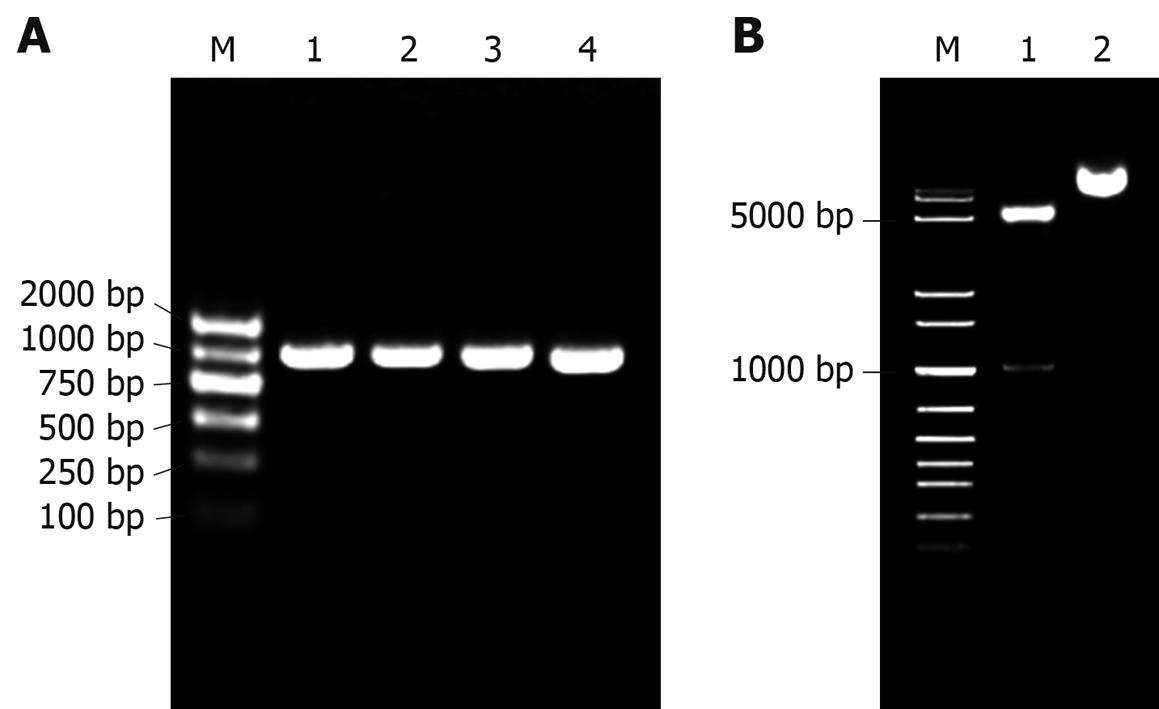

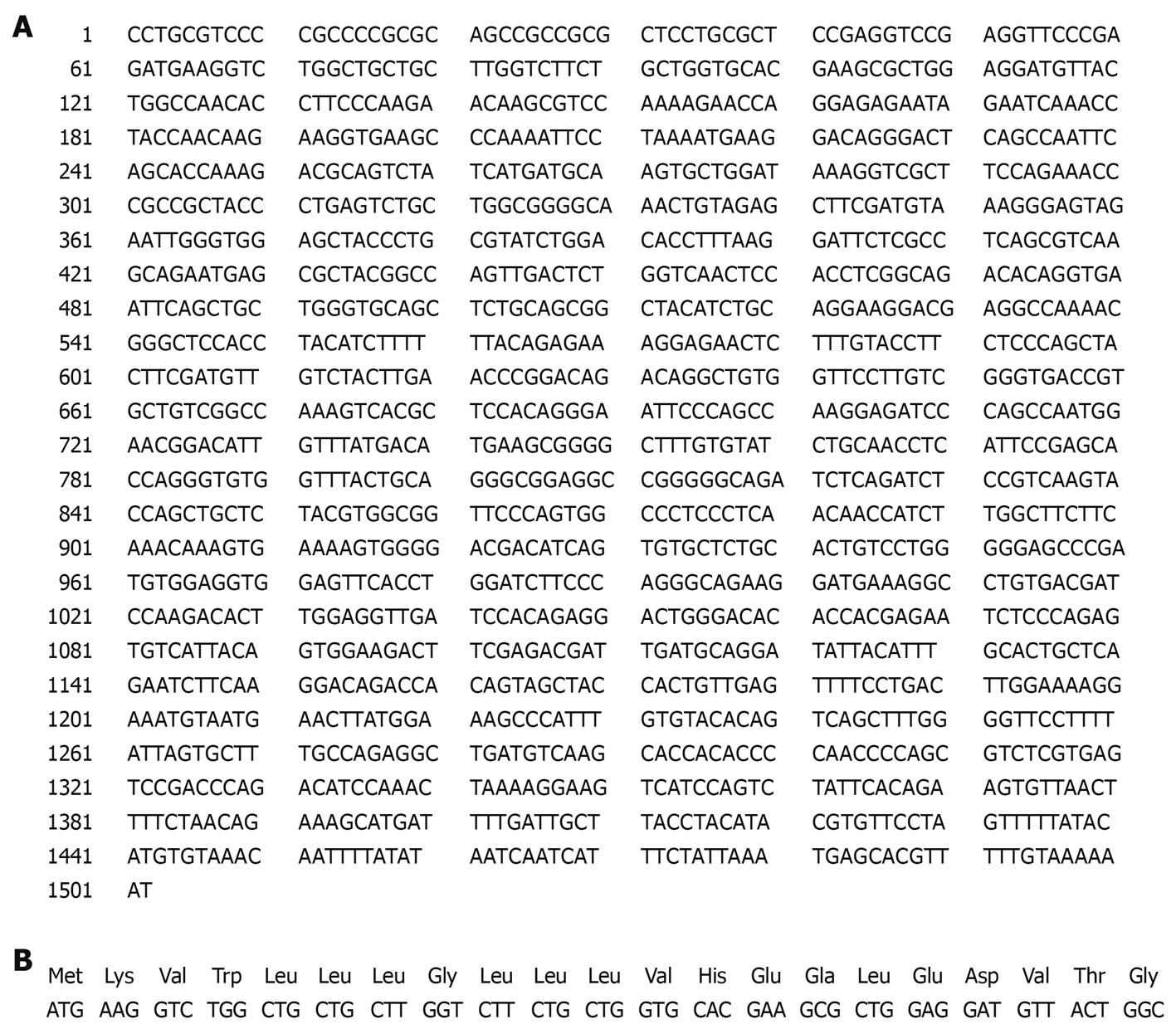

As shown in Figure 2, the prokaryotic expression recombinant pET22b-PDGFRL was successfully constructed using bacterial colony PCR (Figure 2A), restriction enzyme digestions (Figure 2B) and complete sequencing (data not shown).

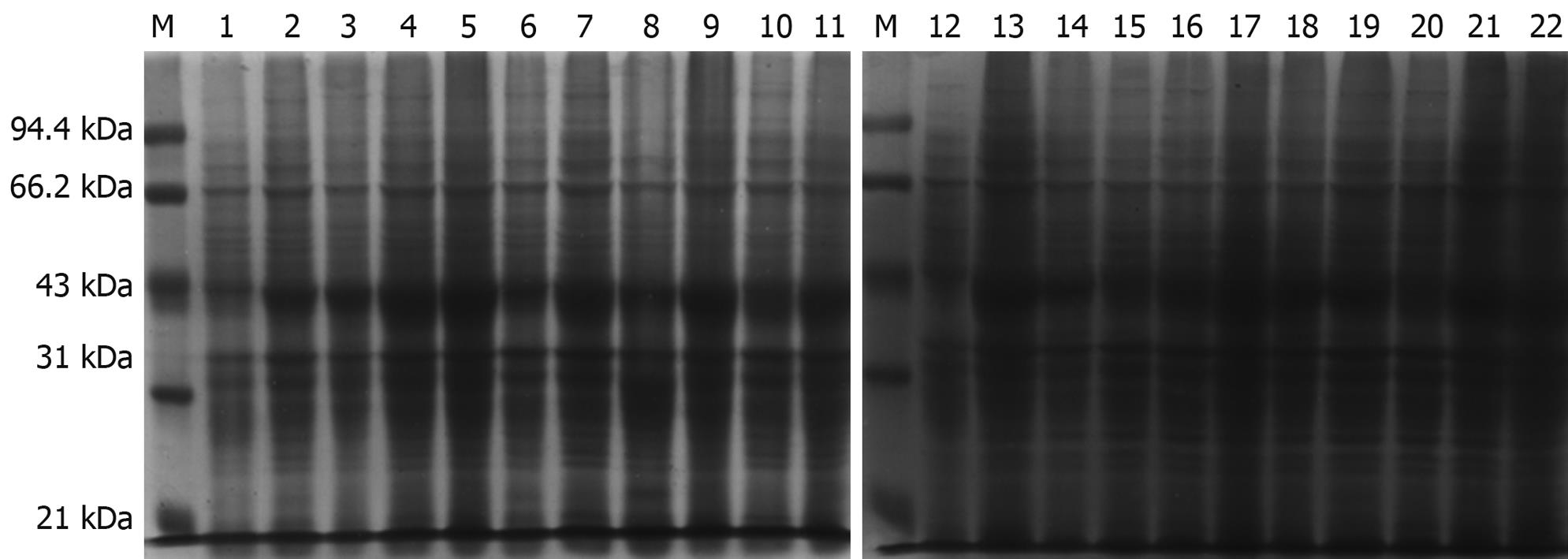

The prokaryotic expressive vector pET22b-PDGFRL was transformed into the E. coli BL21 (DE3) expression host strain for protein over-expression. Several potential clones were identified with DNA sequencing (data not shown). The expression and purification were identified by, respectively, running the crude lysate and the elution fractions on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel and subsequently staining with Coomassie brilliant blue. Experiments of IPTG concentration and time course were performed to determine the kinetics of protein expression in the bacterial culture (Figure 3). As a result, the cells should be harvested 4 h after 0.1 mmol/L IPTG induction, as the largest amount of the correct 42 kDa size pET22b-PDGFRL protein was produced at this time and concentration point.

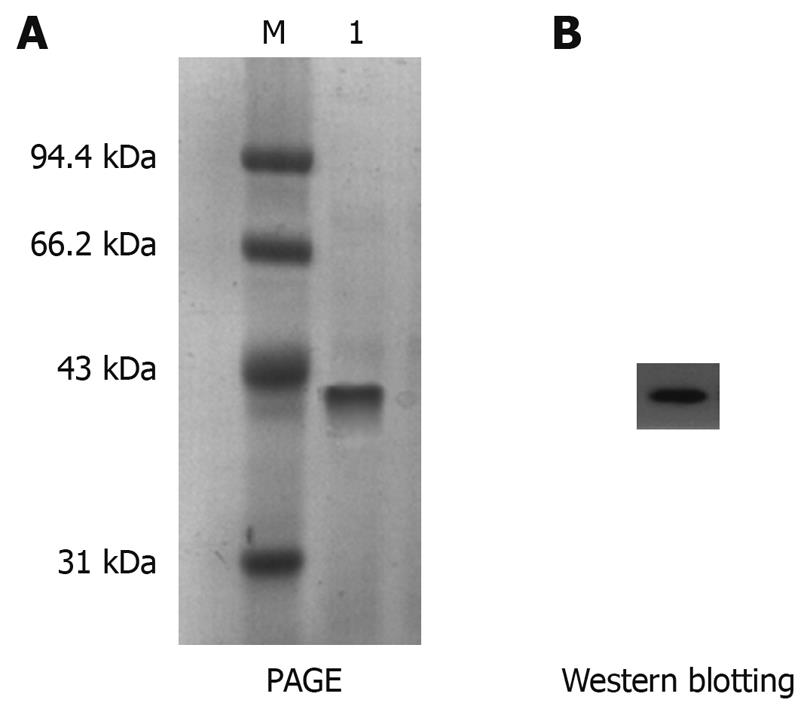

The expressed protein at 0.1 mmol/L IPTG for 4 h was further purified by immobilized metal affinity chromatography. The electrophoretic analysis revealed that the His-tagged His-PDGFRL recombinant protein was purified to near homogeneity and migrated as a 42 kDa band (Figure 4A). Moreover, the purification of the recombinant protein was confirmed by immunoblotting using anti-His-Tag antibody (Figure 4B).

MTT assay was performed to measure the effect on cell viability. HCT-116 cells were found to grow slowly compared with HUVEC cells after PDGFRL protein was added (Figure 5A). The proliferating ability of HCT-116 cells decreased gradually with an increasing concentration of PDGFRL, but normal cell line HUVEC had no evident change in proliferation. Next, we treated HCT-116 cells with rhPDGFRL or BSA, and found that the cell viability of HCT-116 treated with rhPDGFRL (HCT-116/rhPDGFRL) decreased compared with that treated with BSA (HCT-116/BSA), which was not distinguishable from blank group (Figure 5B). A similar pattern of inhibitory effect of rhPDGFRL in HCT-116 cells was achieved in colony formation assay (Figure 6). Following incubation for 2 wk, a few colonies from HCT-116/rhPDGFRL cells were generated compared with HCT-116 or HCT-116/BSA. Therefore, the low MTT activity and a small number of cell colonies from HCT-116/rhPDGFRL cells demonstrated that rhPDGFRL inhibited the growth of HCT-116 cells in vitro.

To further explore the cause of the decrease in cell viability, we examined the effects of PDGFRL on cell cycle. As illustrated in Figure 7, HCT-116 cells treated with PDGFRL blocked the cell cycle in G1 phase. The G0/G1-phase fraction increased from 57.8% (HCT-116/BSA) to 89.4% (HCT-116/rhPDGFRL). These data indicated that PDGFRL arrested HCT-116 cell cycling at the G0/G1 phase, which may inhibit the growth of HCT-116 cells.

We examined the impact of PDGFRL on the migration of HCT-116 cells by the wound healing assay as shown in Figure 8. Following incubation of physically wounded cells for 48 h, the mobile distance of HCT-116/rhPDGFRL cells was found significantly shorter than that of controls.

Despite curative surgery, nearly 4 out of 10 patients with CRC experience disease relapse, 1 of 5 will develop liver metastases, and 1 of 12 will develop pulmonary metastases[14]. The survival of CRC patients is still a key issue to address and the need for drugs curing CRC is urgent.

The tools and concept of gene therapy are being applied to the development of new effective treatment strategies for human cancer[15]. Most human cancers are associated with multiple interacting and cooperating mutations in protooncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Cancer therapies that target oncogenes usually seek to block or reduce their action, while those aimed at tumor suppressor genes seek to restore or increase their action. In several model systems, some features of the tumor phenotype can be suppressed in vitro through the restoration of expression of tumor suppressor genes such as Rb and p53[16,17]. It is interesting that most investigators have found that pVHL suppresses tumourigenicity in a nude mouse assay but not in vitro[18,19]. Protein phosphatase-2A (PP2A) has progressively been considered as a potential tumor suppressor. PP2A activation by forskolin, 1,9-dideoxy-forskolin and FTY720 effectively antagonize leukemogenesis in both in vitro and in vivo models of these cancers[20-22]. PP2A is now a highly promising target for developing a new series of anticancer agents potentially capable of overcoming the drug-resistance[23]. It is necessary to identify new genes applied in the treatment for CRC.

In this study, both RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry showed that the expression of PDGFRL in colorectal normal tissues was higher than in cancer tissues based on the identification of PDGFRL as a tumor suppressor. To investigate the role of PDGFRL in the anti-cancer therapy for CRC, pET-22b (+) prokaryotic expression vector was used to construct rhPDGFRL.

The pET-22b (+) vector carries an N-terminal pelB signal sequence for potential periplasmic localization, plus optional C-terminal His-tag sequence. However, in our study, periplasmic secretion of PDGFRL protein was too small to collect the purified protein, and most of expressive proteins were produced in an insoluble form in E. coli (data not shown).

PDGFRL cDNA sequences contain an open reading frame (ORF) of 1128-base pairs encoding a protein of 375 amino acids (aa) with a putative signal peptide of 21aa (Figure 9). The signal peptide could not be expressed stably in prokaryotic expression vector in high yield, and therefore the signal peptide was deleted in the construction of the recombinant pET22b-PDGFRL[24,25].

In this report, in vitro bioactivity of PDGFRL was determined by MTT, clone counting, cell cycle and wound healing assay. When PDGFRL protein was added to HCT-116 cells, MTT, clone counting and wound healing assay showed that proliferation and invasion of HCT-116 cells decreased. This result indicated that PDGFRL as a tumor suppressor inhibited the growth of CRC cells. In addition, PDGFRL arrested HCT-116 cell cycling at the G0/G1 phase. The results of this study extended our previous knowledge of PDGFRL as a tumor suppressor in CRC. Further characterization of PDGFRL will provide new insights into the role of PDGFRL in the molecular pathogenesis and therapy of CRC.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer related mortality in the Western world. The incidence of CRC in China has increased rapidly over the past few decades. The molecular mechanism of human carcinogenesis and development of CRC is still not clear.

Mutations in platelet-derived growth factor receptor-like gene (PDGFRL) as a tumor suppressor have been found in individual cancer samples and PDGFRL expression is decreased in the majority of breast cancer cells. Recently PDGFRL is identified to play a central role in the tumor suppressor network by adopting a network perspective. Furthermore, PDGFRL was found to be involved in the suppression of the tumor metastatic phenotype as a strong candidate gene.

This study extended the previous knowledge of PDGFRL as a tumor suppressor in CRC.

Further characterization of PDGFRL will provide new insights into the role of PDGFRL in the molecular pathogenesis and therapy of CRC.

PDGFRL is located in chromosome 8p21.3-8p22, which is commonly deleted in sporadic hepatocellular carcinoma, CRC, breast cancer, and non-small cell lung cancer.

By different methods, the authors analyzed the role of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-like gene in CRC and its possible application in anti-cancer therapy. The manuscript is well-written and the study is conducted appropriately.

| 1. | Ferlay J, Autier P, Boniol M, Heanue M, Colombet M, Boyle P. Estimates of the cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2006. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:581-592. |

| 2. | Sung JJ, Lau JY, Goh KL, Leung WK. Increasing incidence of colorectal cancer in Asia: implications for screening. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:871-876. |

| 3. | Yokota J. Tumor progression and metastasis. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:497-503. |

| 4. | Fujiwara Y, Ohata H, Kuroki T, Koyama K, Tsuchiya E, Monden M, Nakamura Y. Isolation of a candidate tumor suppressor gene on chromosome 8p21.3-p22 that is homologous to an extracellular domain of the PDGF receptor beta gene. Oncogene. 1995;10:891-895. |

| 5. | Yaremko ML, Kutza C, Lyzak J, Mick R, Recant WM, Westbrook CA. Loss of heterozygosity from the short arm of chromosome 8 is associated with invasive behavior in breast cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1996;16:189-195. |

| 6. | Komiya A, Suzuki H, Ueda T, Aida S, Ito N, Shiraishi T, Yatani R, Emi M, Yasuda K, Shimazaki J. PRLTS gene alterations in human prostate cancer. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1997;88:389-393. |

| 7. | Lerebours F, Olschwang S, Thuille B, Schmitz A, Fouchet P, Buecher B, Martinet N, Galateau F, Thomas G. Fine deletion mapping of chromosome 8p in non-small-cell lung carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1999;81:854-858. |

| 8. | An Q, Liu Y, Gao Y, Huang J, Fong X, Liu L, Zhang D, Zhang J, Cheng S. Deletion of tumor suppressor genes in Chinese non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 2002;184:189-195. |

| 9. | Kahng YS, Lee YS, Kim BK, Park WS, Lee JY, Kang CS. Loss of heterozygosity of chromosome 8p and 11p in the dysplastic nodule and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:430-436. |

| 10. | Seitz S, Korsching E, Weimer J, Jacobsen A, Arnold N, Meindl A, Arnold W, Gustavus D, Klebig C, Petersen I. Genetic background of different cancer cell lines influences the gene set involved in chromosome 8 mediated breast tumor suppression. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006;45:612-627. |

| 11. | Xu M, Kao MC, Nunez-Iglesias J, Nevins JR, West M, Zhou XJ. An integrative approach to characterize disease-specific pathways and their coordination: a case study in cancer. BMC Genomics. 2008;9 Suppl 1:S12. |

| 12. | Riker AI, Enkemann SA, Fodstad O, Liu S, Ren S, Morris C, Xi Y, Howell P, Metge B, Samant RS. The gene expression profiles of primary and metastatic melanoma yields a transition point of tumor progression and metastasis. BMC Med Genomics. 2008;1:13. |

| 13. | Huang SF, Liu DB, Zeng JM, Xiao Q, Luo M, Zhang WP, Tao K, Wen JP, Huang ZG, Feng WL. Cloning, expression, purification and functional characterization of the oligomerization domain of Bcr-Abl oncoprotein fused to the cytoplasmic transduction peptide. Protein Expr Purif. 2009;64:167-178. |

| 14. | Kievit J. Follow-up of patients with colorectal cancer: numbers needed to test and treat. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:986-999. |

| 15. | Friedmann T. Gene therapy of cancer through restoration of tumor-suppressor functions. Cancer. 1992;70:1810-1817. |

| 16. | Bykov VJ, Selivanova G, Wiman KG. Small molecules that reactivate mutant p53. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:1828-1834. |

| 17. | Cristofanilli M, Krishnamurthy S, Guerra L, Broglio K, Arun B, Booser DJ, Menander K, Van Wart Hood J, Valero V, Hortobagyi GN. A nonreplicating adenoviral vector that contains the wild-type p53 transgene combined with chemotherapy for primary breast cancer: safety, efficacy, and biologic activity of a novel gene-therapy approach. Cancer. 2006;107:935-944. |

| 18. | Chen F, Kishida T, Duh FM, Renbaum P, Orcutt ML, Schmidt L, Zbar B. Suppression of growth of renal carcinoma cells by the von Hippel-Lindau tumor suppressor gene. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4804-4807. |

| 19. | Iliopoulos O, Kibel A, Gray S, Kaelin WG Jr. Tumour suppression by the human von Hippel-Lindau gene product. Nat Med. 1995;1:822-826. |

| 20. | Neviani P, Santhanam R, Oaks JJ, Eiring AM, Notari M, Blaser BW, Liu S, Trotta R, Muthusamy N, Gambacorti-Passerini C. FTY720, a new alternative for treating blast crisis chronic myelogenous leukemia and Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2408-2421. |

| 21. | Feschenko MS, Stevenson E, Nairn AC, Sweadner KJ. A novel cAMP-stimulated pathway in protein phosphatase 2A activation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:111-118. |

| 22. | Matsuoka Y, Nagahara Y, Ikekita M, Shinomiya T. A novel immunosuppressive agent FTY720 induced Akt dephosphorylation in leukemia cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;138:1303-1312. |

| 23. | Perrotti D, Neviani P. Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), a drugable tumor suppressor in Ph1(+) leukemias. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008;27:159-168. |

| 24. | D'Costa S, Kulik MJ, Petitte JN. Expression and purification of biologically active recombinant quail stem cell factor in E. coli. Cell Biol Int. 2000;24:311-317. |

| 25. | Sun Y, Zhang JJ, Han TT, Li DL, Cao XM, Li WX, Gao YG. [Preparation and characterization of anti-Amelotin polyclonal antibody]. Xibao Yu Fenzimianyixue Zazhi. 2009;25:328-331. |

Peer reviewers: Dr. Lucia Ricci Vitiani, Department of Hematology, Oncology and Molecular Medicine, Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Viale Regina Elena, 299, Rome, 00161, Italy; Dr. Abdel-Majid Khatib, PhD, INSERM, UMRS 940, Equipe Avenir, Cibles Thérapeutiques, IGM 27 rue Juliette Dodu, 75010 Paris, France

S- Editor Wang JL L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Lin YP