Published online Feb 7, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.591

Revised: December 29, 2008

Accepted: January 5, 2009

Published online: February 7, 2009

AIM: To evaluate different biochemical markers and their ratios in the assessment of primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) stages.

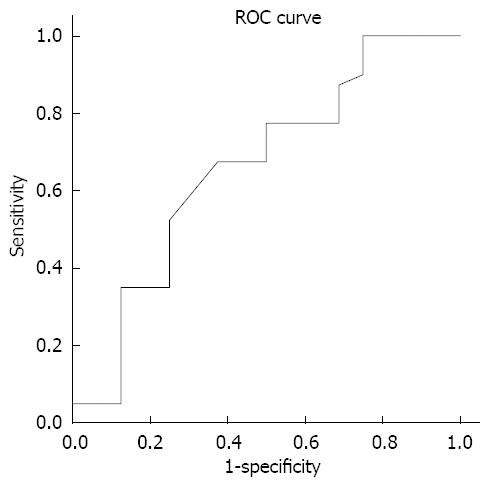

METHODS: This study included 112 patients with PBC who underwent a complete clinical investigation. We analyzed the correlation (Spearman's test) between ten biochemical markers and their ratios with different stages of PBC. The discriminative values were compared using areas under receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves.

RESULTS: The mean age of patients included in the study was 53.88 ± 10.59 years, including 104 females and 8 males. We found a statistically significant correlation between PBC stage and Aspartate aminotransferase (AST), Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) to platelet ratio (APRI), ALT/platelet count, AST/ALT, ALT/AST and ALT/Cholesterol ratios, with the values of Spearman’s rho of 0.338, 0.476, 0.404, 0.356, 0.351 and 0.325, respectively. The best sensitivity and specificity was shown for AST/ALT, with an area under ROC of 0.660.

CONCLUSION: Biochemical markers and their ratios do correlate with different sensitivity to and specificity of PBC disease stage. The use of biochemical markers and their ratios in clinical evaluation of PBC patients may reduce, but not eliminate, the need for liver biopsy.

- Citation: Alempijevic T, Krstic M, Jesic R, Jovanovic I, Milutinovic AS, Kovacevic N, Krstic S, Popovic D. Biochemical markers for non-invasive assessment of disease stage in patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(5): 591-594

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i5/591.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.591

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a slowly progressive autoimmune disease of the liver that primarily affects women. Its peak incidence occurs in the fifth decade of life, and it is uncommon in persons under 25 years of age. PBC is diagnosed more frequently than it was a decade ago because of its greater recognition by physicians, the widespread use of automated blood testing and the antimitochondrial antibody test, which is relatively specific for the diseases[12]. Histologically, PBC is characterized by portal inflammation and immune-mediated destruction of the intrahepatic bile ducts. These changes occur at different rates and with varying degrees of severity in different patients. The loss of bile ducts leads to decreased bile secretion and the retention of toxic substances within the liver. This results in further hepatic damage, fibrosis, cirrhosis, and eventually, liver failure[3].

Liver biopsy is necessary to assess the extent of liver damage in an anicteric patient, e.g. in a patient in whom a transplantation is considered because of heavy symptom load. A liver biopsy may also be desirable to detect cirrhosis indicating a need for esophagogastroscopy for the detection of oesophageal varices or it may reveal a relative contraindication for treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid, which is effective only in early stages of PBC[45].

For both, the physician and the patient, the decision to proceed with a liver biopsy is not trivial one. Furthermore, many patients are reluctant to experience repeated biopsies, which limits our ability to monitor disease progression and the effects of treatments. Significant complications, defined as requiring hospital admission or prolonged hospital stay, occurs in 1%-5% of patients who have a liver biopsy, while the reported mortality rate varies between 1:1000 and 1:10 000[67]. Most, but not all, studies have shown that the incidence of complications is related to both the presence of relative contraindications and the number of biopsies taken[68]. Despite these reservations, needle liver biopsy has been used as the “gold standard” for the assessment of liver fibrosis. However, a review of the available data on the accuracy of needle liver biopsy to define the stage of fibrosis reveals that the assessment of liver fibrosis is affected by significant sampling and interpretative errors. Therefore, while liver biopsy remains the “gold standard”, both the clinician and the researcher should view the result of liver biopsy with some reservation and should interpret the findings in the broader clinical context. These problems must be considered when assessing the performance of other non-invasive tests for fibrosis when needle biopsy is used as the “gold standard”. Many fibrosis experts would therefore consider serum fibrosis tests with an ROC area of 0.85-0.90 to be as good as liver biopsy for staging fibrosis.

The aim of our study is to evaluate different biochemical markers and their ratios in assessment of various stages of PBC[9].

This study includes 112 patients investigated and treated for primary biliary cirrhosis in Clinic for Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Clinical Centre of Serbia during 2006. The diagnosis was based on clinical features, laboratory test, imaging diagnostics, and whenever possible, on liver histology.

The following information was collected for each patient: age, gender, biochemical parameters [aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), albumin, ALT to platelet ratio (APRI), AST/ALT ratio, ALT/AST ratio, ALT/alkaline phosphatase (AF) ratio, ALT/gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT) ratio, ALT/cholesterol (Chol) ratio], and the histological stage of the disease.

Stage I-IV classification of the disease was applied by an experienced pathologist who assessed the liver biopsies. Stage I is defined by the localization of inflammation to the portal triads. In stage II, the number of normal bile ducts is reduced, and the inflammation extends beyond the portal triads into the surrounding parenchyma. Fibrous septa link adjacent to portal triads in stage III, while stage IV represents the end-stage liver disease, characterized by obvious cirrhosis with regenerative nodules[10].

Laboratory testing and needle biopsy of livers were performed within a maximum of one week.

The Ethics Committee of our institution approved the study and all patients gave informed consent prior to inclusion in this investigation.

All collected data were analyzed and correlated. Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS®, version 14.0). Basic descriptive statistics included means, standard deviations, ranges and percentages. For correlation analysis, we used Spearman’s test. Differences were considered statistically significant if the two-tailed P value was less than 0.05. Confidence intervals and the best cut-off values for the assessment of disease stage were calculated using ROC curves.

The study included 112 patients with PBC who underwent a complete clinical investigation. The mean age of patients included in the study was 53.88±10.59 years. (range 29-76), 104 females and 8 males. There were 58 (51.8%) patients in PBC stage I, 20 (17.9%) in stage II 20, 24 in stage III (21.4%), and the remaining 10 patients (8.9%) were in stage IV, characterized by liver cirrhosis. In fact, 78 patients (69.7%) had a mild form of PBC (stages I and II), while 34 patients (30.3%) showed an advanced form of the disease (stages III and IV). Values of analyzed biochemical markers, as well as results of statistical analyses are presented in Table 1. We found a statistical significant correlation between PBC stage and AST, APRI, ALT/platelet, AST/ALT, ALT/AST and ALT/Chol ratio, with the values of Spearman’s rho of 0.338, 0.476, 0.404, 0.356, -0.351 and 0.325, respectively. The best sensitivity and specificity was shown for AST/ALT, with the area under ROC of 0.660.

| mean ± SD | Range | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Confidential interval | Area under ROC | Spearman’s rho | P value | |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (U/L) | 69.41 ± 84.7 | 14-466 | 42.5 | 62.5 | 27.8-63.3 | 0.484 | 0.303 | < 0.05 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) (U/L) | 87.39 ± 105.89 | 13-594 | 40 | 50 | 30.7-60.6 | 0.455 | 0.232 | NS |

| Albumin | 37.67 ± 4.69 | 27-47 | 27.5 | 62.5 | 23.8-54.3 | 0.391 | 0.117 | NS |

| ALT to platelet ratio (APRI) | 0.39 ± 0.42 | 0.06-2.16 | 42.5 | 50 | 23.7-58.7 | 0.412 | 0.351 | < 0.01 |

| AST to platelet ratio | 0.33 ± 0.38 | 0.06-1.70 | 32.5 | 50 | 19.2-53.1 | 0.362 | 0.407 | < 0.01 |

| AST/ALT ratio | 0.81 ± 0.23 | 0.51-1.38 | 47.5 | 75 | 17.0-50.3 | 0.660 | 0.347 | < 0.01 |

| ALT/AST ratio | 1.32 ± 0.34 | 0.73-1.97 | 32.5 | 62.5 | 49.2-82.9 | 0.337 | -0.297 | < 0.05 |

| ALT/ alkaline phosphatase (AF) ratio | 0.42 ± 0.44 | 0.10-2.44 | 35 | 42.8 | 34.0-70.8 | 0.594 | 0.094 | NS |

| ALT/gama glutamyl transferase (GGT) ratio | 0.68 ± 0.94 | 0.12-5.09 | 40 | 56.2 | 33.0-67.0 | 0.502 | 0.38 | NS |

| ALT/cholesterol (Chol) ratio | 13.65 ± 10.87 | 2.5-59.76 | 35 | 50 | 26.0-61.6 | 0.438 | 0.285 | < 0.05 |

During the last decade many studies have been designed to identify non-invasive markers capable of providing accurate information about liver fibrogenesis activity and stage of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic, potentially progressive hepatic diseases. The ideal characteristics of such markers are: (1) Specific for liver fibrosis; (2) Providing measurement of: (a) stage of fibrosis, (b) fibrogenesis activity; (3) Not influenced by comorbidities (e.g. renal, reticulo-endothelial); (4) Known half-life; (5) Known excretion route; (6) Sensitive; and (7) Reproducible. Two quite different approaches have been followed. Many studies have evaluated “direct” markers of fibrogenesis, i.e. of biochemical parameters, measurable in the peripheral blood as a direct expression of either the deposition or the removal of ECM in the liver. These direct markers of liver fibrosis include several glycoproteins (hyaluronan, laminin, human cartilage glycoprotein 39 (YKL-40), the collagens family (procollagen III, type IV collagen and type IV collagen 7s domain), the collagenases and their inhibitors (metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases) and a number of cytokines connected with the fibrogenetic process (TGF-β1, TNF-β). A second and easier approach in the search of non-invasive markers of liver fibrosis has been choosing single or combined hematological and/or biochemical parameters that reflect the stage of liver disease, and assessing and comparing the accuracy of their diagnostic performance. This approach, using routinely performed blood tests, has led to the identification of sets of markers able to define the stage of liver fibrosis with accuracy very similar, if not superior, to that of the more sophisticated and difficult to test direct markers. The diagnostic performance of most direct and indirect markers of liver fibrosis has been investigated in all the common etiological forms of chronic liver diseases, including hepatitis C, hepatitis B and alcoholic and non alcoholic fatty liver disease and steatohepatitis, although some of them have been more extensively tested in patients with chronic hepatitis C[11].

There are many published articles on non-invasive assessment of fibrosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection, but only one published article[12] analyzed the value of AST/ALT ratio as an indicator of cirrhosis in patients with PBC. This study included 160 patients with PBC and for 121 they had laboratory data and liver histology. The authors of the study analyzed the clinical and laboratory data, as well as follow-up outcomes: liver-related death, liver transplantation and survival. The AST/ALT ratio was also used for assessment in alcohol-induced liver cirrhosis prediction of oesophageal varices and ascites presence. It is suggested that the AST/ALT ration increases in patients who develop liver cirrhosis, regardless of its cause. The reason for the increased AST/ALT ratio is unknown. It is suggested that the sinusoidal clearance of AST decreases in cirrhotic patients[13–15]. Nyblom et al[14] reported the use of this ratio for discrimination between cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic patients with sensitivity of 82% and specificity of 79%, for a cut-off value 1.1. The explanation for such high sensitivity is that a large number of cirrhotic patients were included, while sampling variability in the liver biopsies contributed to low specificity. The study concluded that the AST/ALT ratio is of clinical value as a predictor of cirrhosis in patients with PBC, but not as a prognostic factor.

Our study explored the value of different biochemical markers in the assessment of a range of disease stages in PBC patients. The sensitivity and specificity was calculated to discriminate early (stages I and II) vs advanced (stages III and IV) stages of PBC. We showed that several biochemical markers could be successfully used for staging the disease. Our results are, to some extent, comparable with the results of the previous similar studies, while the observed lower sensitivity (47.5%) and specificity (75%) for the AST/ALT ratio (Figure 1) could be explained by different study design.

New technology has been developed based on the fact that liver stiffness (LS) increases as liver fibrosis progresses[16]. The FibroScan 502 (FS, EchoSens, Paris, France) for transient elastography is a new modality developed for non-invasive evaluation of LS. LS correlated well with the histological stage of fibrosis. Changes in liver fibrosis stage may thus be estimated non-invasively using transient elastography[1718]. Nevertheless, further studies are needed to confirm the value of this technique in different chronic diseases of liver.

In our opinion, the potential predictive value of aminotransferase and platelet count ratios in prediction of PBC stage may be used in evaluation of PBC evolution, despite their limited sensitivity and specificity, especially when considering their availability and cost effectiveness. Combination panels of non-invasive biomarkers may improve the accuracy of the single tests.

The main goal of this study was to evaluate different biochemical markers and their ratios in assessment of various stages of primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC).

Despite liver biopsy remaining the “gold standard”, there is great clinical interest in the use of non-invasive methods to assess disease stage in primary biliary cirrhosis.

This study explored the value of different biochemical markers in assessment of a range of disease stages in PBC patients. The sensitivity and specificity was calculated to discriminate early (stages I and II) vs advanced (stages III and IV) stages of PBC. We showed that several biochemical markers could be successfully used for staging the disease.

Use of biochemical markers and their ratios in clinical evaluation of PBC patients may reduce, but not eliminate, the need for liver biopsy. The potential predictive value of aminotransferase and platelet count ratios in prediction of PBC stage may be used in evaluation of PBC evolution, despite their limited sensitivity and specificity, especially when considering their availability and cost effectiveness.

This is a simple and elegant study that increases our knowledge of the non-invasive evaluation of biliary cirrhosis staging.

| 1. | Kaplan MM. Primary biliary cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1570-1580. |

| 2. | Kaplan MM. Primary biliary cirrhosis: past, present, and future. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1392-1394. |

| 3. | Myszor M, James OF. The epidemiology of primary biliary cirrhosis in north-east England: an increasingly common disease? Q J Med. 1990;75:377-385. |

| 4. | Kaplan MM, Gershwin ME. Primary biliary cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1261-1273. |

| 5. | Corpechot C, Carrat F, Bahr A, Chretien Y, Poupon RE, Poupon R. The effect of ursodeoxycholic acid therapy on the natural course of primary biliary cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:297-303. |

| 6. | Cadranel JF, Rufat P, Degos F. Practices of liver biopsy in France: results of a prospective nationwide survey. For the Group of Epidemiology of the French Association for the Study of the Liver (AFEF). Hepatology. 2000;32:477-481. |

| 7. | Thampanitchawong P, Piratvisuth T. Liver biopsy:complications and risk factors. World J Gastroenterol. 1999;5:301-304. |

| 8. | Froehlich F, Lamy O, Fried M, Gonvers JJ. Practice and complications of liver biopsy. Results of a nationwide survey in Switzerland. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1480-1484. |

| 9. | Terjung B, Lemnitzer I, Dumoulin FL, Effenberger W, Brackmann HH, Sauerbruch T, Spengler U. Bleeding complications after percutaneous liver biopsy. An analysis of risk factors. Digestion. 2003;67:138-145. |

| 10. | Afdhal NH, Nunes D. Evaluation of liver fibrosis: a concise review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1160-1174. |

| 11. | Sherlock S, Scheuer PJ. The presentation and diagnosis of 100 patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1973;289:674-678. |

| 12. | Sebastiani G, Alberti A. Non invasive fibrosis biomarkers reduce but not substitute the need for liver biopsy. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3682-3694. |

| 13. | Nyblom H, Bjornsson E, Simren M, Aldenborg F, Almer S, Olsson R. The AST/ALT ratio as an indicator of cirrhosis in patients with PBC. Liver Int. 2006;26:840-845. |

| 14. | Nyblom H, Berggren U, Balldin J, Olsson R. High AST/ALT ratio may indicate advanced alcoholic liver disease rather than heavy drinking. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39:336-339. |

| 15. | Park GJ, Lin BP, Ngu MC, Jones DB, Katelaris PH. Aspartate aminotransferase: alanine aminotransferase ratio in chronic hepatitis C infection: is it a useful predictor of cirrhosis? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:386-390. |

| 16. | Williams AL, Hoofnagle JH. Ratio of serum aspartate to alanine aminotransferase in chronic hepatitis. Relationship to cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:734-739. |

| 17. | Yeh WC, Li PC, Jeng YM, Hsu HC, Kuo PL, Li ML, Yang PM, Lee PH. Elastic modulus measurements of human liver and correlation with pathology. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2002;28:467-474. |

| 18. | Takeda T, Yasuda T, Nakayama Y, Nakaya M, Kimura M, Yamashita M, Sawada A, Abo K, Takeda S, Sakaguchi H. Usefulness of noninvasive transient elastography for assessment of liver fibrosis stage in chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7768-7773. |