Published online Nov 14, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.5360

Revised: September 19, 2009

Accepted: September 26, 2009

Published online: November 14, 2009

Bacillus species are aerobic, gram-positive, spore forming rods that are usually found in the soil, dust, streams, and other environmental sources. Except for Bacillus. anthracis (B. anthracis), most species display low virulence, and only rarely cause infections in hosts with weak or damaged immune systems. There are two case reports of B. cereus as a potentially serious bacterial pathogen causing a liver abscess in an immunologically competent patient. We herein report a case of liver abscess and sepsis caused by B. pantothenticus in an immunocompetent patient. Until now, no case of liver abscess due to B. pantothenticus has been reported.

-

Citation: Na JS, Kim TH, Kim HS, Park SH, Song HS, Cha SW, Yoon HJ. Liver abscess and sepsis with

Bacillus pantothenticus in an immunocompetent patient: A first case report. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(42): 5360-5363 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i42/5360.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.5360

Bacillus species are aerobic, or facultatively anaerobic, gram-positive or gram-variable spore-forming rods. They are ubiquitous in the environment and are found in water, dirt, air, stools, and plant surfaces. They are relatively resistant to heat, due to spore formation, and they therefore grow easily during the storage of food and produce toxins that can cause food poisoning[1-3]. The pathogenicity of Bacillus. anthracis (B. anthracis) is well known in mammals. Nonanthrax species within clinical materials, which were previously considered contaminants, have increasingly been identified as pathogens[4]. One of the nonanthrax species, B. cereus is reported in most cases as a human pathogen[4]. Occasional reports have appeared implicating other nonanthrax species, for example, B. thuringiensis, B. alvei, B. circulans, B. licheniformis, B. macerans, B. pumilus, B. sphaericus, and B. subtilis in systemic and gastrointestinal diseases[3,4]. However, B. pantothenticus has not been reported as a human pathogen in any English-language literature since 1950. Here, we report a case of liver abscess and sepsis caused by B. pantothenticus in an immunocompetent man who was successfully treated with cefotaxime and Netilmicin, followed by oral ciprofloxacin.

The patient, a 44-year-old man, was admitted to hospital complaining of high fever (40.2°C) and abdominal discomfort in right upper quadrant. A week before admission, he had been on a bicycle trip for two days alone and had eaten raw saltwater fish, which he had cleaned and cut himself. His past medical history was unremarkable.

His physical examination showed a body temperature of 40.2°C, blood pressure of 170/90 mmHg, a respiration rate of 20 breaths/min and a heart rate of 106 beats/min. He had tenderness on the right upper quadrant of his abdomen. Other findings were unremarkable.

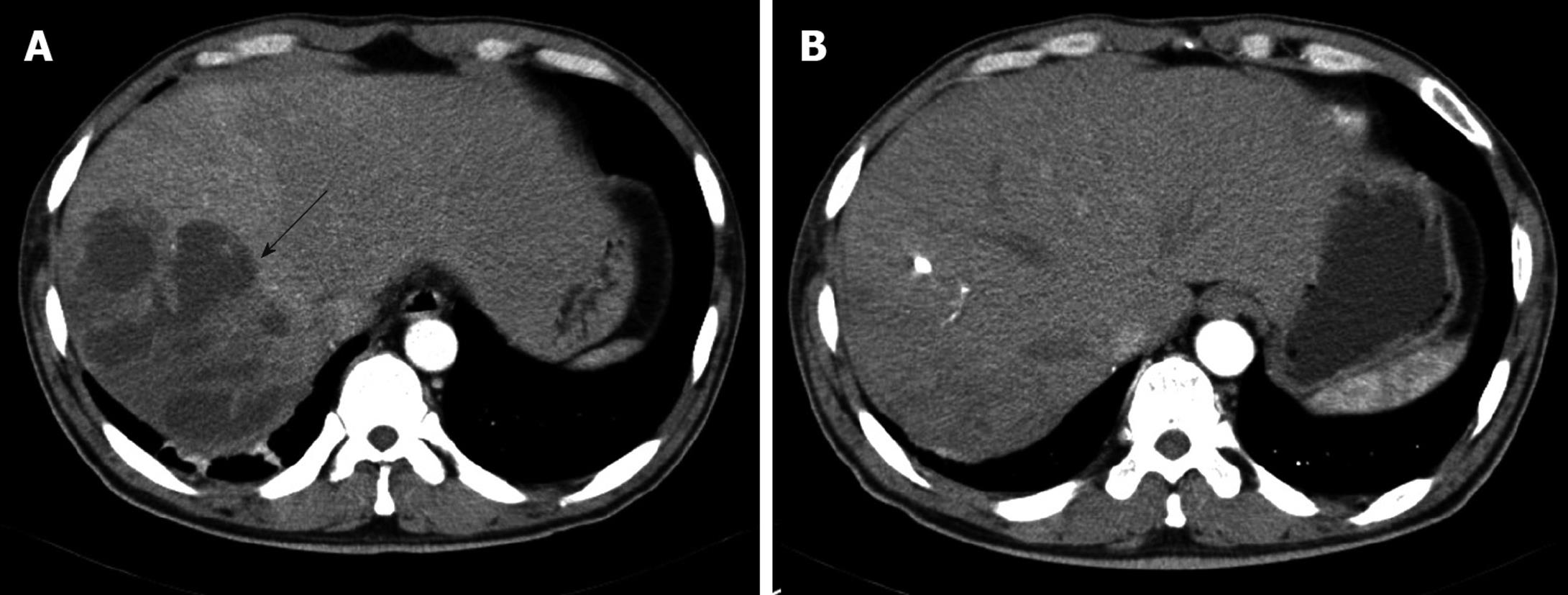

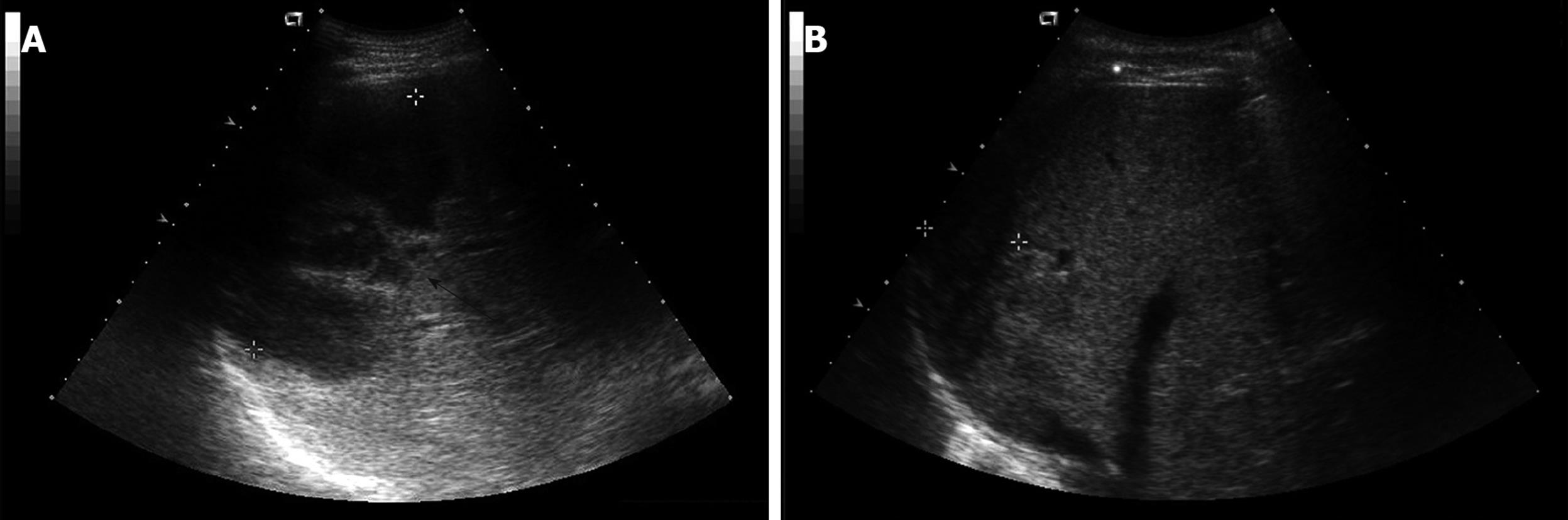

Laboratory studies were as follows: hemoglobin concentration 12.6 g/dL; hematocrit 35.65%; leukocytes 16 650/mm3 (granulocytes 82.7%, lymphocytes 9.6%, and monocytes 5.0%); platelets 435 000/mm3; erythrocyte sedimentation rate 120 mm/h; C-reactive protein (CRP) 27.72 mg/dL; aspartate aminotransferase 121 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase 164 IU/L; γ-glutamyl transpeptidase 284 IU/L; alkaline phosphatase 397 IU/L; total bilirubin 1.5 mg/dL. Serologic assays for hepatitis A, B and C were negative. All other laboratory values were normal. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a multi-loculated liver abscess (12 cm × 9 cm) in the posterior inferior (VI segment) and posterior superior segment of the right lobe (VII segment) of the liver (Figure 1A and Figure 2A). After blood samples had been drawn for culture, empirical antibiotic therapy with cefotaxime, Netilmicin, and metronidazole was started. Two days later, a percutaneous drainage was performed. A purulent and odorous material was obtained, and it was immediately inoculated into aerobic and anaerobic culture material.

On the 6th hospital day, the results of blood cultures showed B. pantothenticus in all six blood sets that were sensitive to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, erythromycin, gentamicin, oxacillin, teicoplanin, tetracycline, and vancomycin. In addition, amoeba antibodies were negative. Therefore, we discontinued metronidazole and maintained cefotaxime and Netilmicin. The culture of purulent material at drainage showed no growth of bacteria. On the 30th hospital day, a follow up CT scan was performed, which showed no abscess pocket (Figure 1B). Follow-up blood cultures grew no bacteria and he was discharged with oral ciprofloxacin. The patient has been followed up with control visits and has shown no sign of a recurrence. Abdominal ultrasonography after 51 d of treatment showed a completely healed abscess pocket and remaining post-inflammatory changes (Figure 2B).

Bacillus species, except for B. anthracis, rarely cause serious human infections. Occasionally, Bacillus species can be pathogens in certain clinical situations (e.g. patients with intravenous drug abuse, trauma, cancer, neutropenia, leukemia, receiving chemotherapy or indwelling central venous catheter) but are not usually pathogenic to immunocompetent individuals[5-7]. Clinical infections caused by Bacillus species (probably B. cereus in most cases) fall into six broad groups: (1) local infections, particularly of burns, traumatic or post-surgical wounds, and the eye; (2) bacteremia and septicemia; (3) central nervous system infections, including meningitis, abscesses, and shunt-associated infections; (4) respiratory infections; (5) endocarditis and pericarditis; and (6) food poisoning, characterized by toxin-induced emetic and diarrheagenic syndromes[2].

B. pantothenticus was first described by Proom & Knight, following a nutritional analysis of mesophilic soil isolates of Bacillus species[8]. It was named because this strain required pantothenic acid to isolate it from different soil samples. They considered it to a species most closely resembling B. circulans but distinct from it, and subsequent studies confirmed the validity of the species[9-11]. Later isolations have been made from antacids, food, water, and soil[9]. In the present case, the raw fish that the patient had eaten might have been contaminated with B. pantothenticus.

Organisms recovered from liver abscesses vary with the etiology. In liver infection arising from the biliary tree, enteric gram-negative aerobic bacilli and enterococci are common isolates[12]. Unless previous surgery has been performed, anaerobes are not generally involved in liver abscesses arising from biliary infections. In contrast, in liver abscesses arising from pelvic and other intraperitoneal sources, a mixed flora, including aerobic and anaerobic species (especially Bacteroides fragilis), is common[12]. With hematogenous spread of infection, usually only a single organism is encountered; this species may be Staphylococcus aureus or a streptococcal species, such as Streptococcus milleri. Liver abscesses may also be caused by Candida species[12]. Amoebic liver abscesses remain a common clinical finding[13].

We conducted a thorough keyword search for other cases of liver abscess due to B. pantothenticus in the web-based Medline database, but found none. However, there were two cases of liver abscess due to B. cereus. In one case, the patient was in good health[13], but was admitted to hospital because of fever and, on CT scan, a liver abscess was shown. The treatment was started by empirical antibiotics and surgically drained, but the patient died on the 4th postoperative day due to acute peritonitis. B. cereus was isolated from a culture of the purulent material[13]. In the second case, the patient was diagnosed as Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) two years previously and admitted to hospital because of relapse of ALL[14]. B. cereus was isolated on blood culture. Multiple abscesses were found in the brain by magnetic resonant imaging (MRI) and in the liver by abdominal ultrasonography and computed tomography. B. cereus is susceptible to Minocycline, vancomycin, levofloxacin, and chloramphenicol and therefore they were administered to the patient. One month later, the multiple liver abscesses had disappeared but the patient died four months later due to deteriorated leukemia[14].

The isolation of Bacillus species from blood cultures is clinically significant in 5%-10% of cases[15]. In the present case, B. pantothenticus was grown in six sets of blood cultures from different veins, with 30 min intervals between sets; thus we assume it is the true pathogen. The reason of for non-growth of B. pantothenticus in the purulent discharge might be the previous use of antibiotics before drainage.

Weber et al[16] tested 54 B. cereus isolates and 35 non-cereus Bacillus isolates for antimicrobial susceptibility and found almost uniform susceptibility to vancomycin, imipenem, gentamicin, and ciprofloxacin. Most non-cereus Bacillus isolates were susceptible to penicillins and cephalosporins, but almost B. cereus isolates were resistant to penicillins or cephalosporins, due to the presence of beta-lactamase[2,16]. Therefore, vancomycin appears to be the best treatment for Bacillus species infection, before the results of specific susceptibility are available[16]. However, B. cereus is also susceptible to clindamycin, gentamicin, chloramphenicol, and erythromycin[2,7,17-19]. In our case, empirical antimicrobial treatment with cefotaxime, Netilmicin and metronidazole for liver abscess was started before B. pantothenticus was isolated in blood culture. After B. pantothenticus was identified, we discontinued metronidazole. We continued cefotaxime and Netilmicin, as most non-cereus Bacillus isolates are susceptible to cephalosporins. B. pantothenticus showed sensitivity to gentamicin and most importantly, the patient’s clinical and laboratory course was improving with these antibiotics. Pyogenic liver abscesses are usually treated parenterally for two to three weeks, and for the following four to six weeks with oral agents. The patient’s clinical response and follow-up imaging should be monitored to determine his response to therapy, for consideration of antibiotic duration and the need for further aspiration[12]. In this case, clinical and laboratory parameters became normalized and follow-up sonography showed complete healing of the abscess; therefore, we could stop antibiotics on the 51th hospital day.

In conclusion, we report the first case of liver abscess and sepsis caused by B. pantothenticus in an immunocompetent patient. The patient was successfully treated with a course of cefotaxime, Netilmicin, and metronidazole, followed by oral ciprofloxacin. This case demonstrates that unusual organisms can lead to unexpected and severe infections in patients who are previously healthy and have no obvious risk factors. It is important to consider unusual organisms as a cause of systemic infections and arrange appropriate microbiological investigations so as not to miss the clinical diagnosis.

| 1. | Balows A, Hausler WJ Jr, Herrmann KL, Isenberg HD, Shadomy HJ, editors . Manual of clinical microbiology. 5th ed. Washington DC: American Society for Microbiology 1991; 296-303. |

| 2. | Drobniewski FA. Bacillus cereus and related species. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:324-338. |

| 3. | Turnbull PCB, Kramer JM, Melling J. Bacillus. Topley and Wilson's principles of bacteriology, virology and immunity. vol. 2, 8th ed. London: Edward Arnold 1990; 188-210. |

| 4. | Farrar WE Jr. Serious infections due to "non-pathogenic" organisms of the genus Bacillus. Review of their status as pathogens. Am J Med. 1963;34:134-141. |

| 5. | Blue SR, Singh VR, Saubolle MA. Bacillus licheniformis bacteremia: five cases associated with indwelling central venous catheters. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:629-633. |

| 6. | Hernaiz C, Picardo A, Alos JI, Gomez-Garces JL. Nosocomial bacteremia and catheter infection by Bacillus cereus in an immunocompetent patient. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9:973-975. |

| 7. | Orrett FA. Fatal Bacillus cereus bacteremia in a patient with diabetes. J Natl Med Assoc. 2000;92:206-208. |

| 8. | Heyndrickx M, Lebbe L, Kersters K, Hoste B, De Wachter R, De Vos P, Forsyth G, Logan NA. Proposal of Virgibacillus proomii sp. nov. and emended description of Virgibacillus pantothenticus (Proom and Knight 1950) Heyndrickx et al. 1998. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1999;49 Pt 3:1083-1090. |

| 9. | Claus D, Berkeley RCW. Genus Bacillus Cohn 1872. Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins 1986; 1105-1139. |

| 10. | Gordon R, Em Haynes WC, Pang CHN. The genus bacillus. Agriculture handbook, No. 427. Washington DC: US Department of Agriculture 1973; 283. |

| 11. | Logan NA, Berkeley RC. Identification of Bacillus strains using the API system. J Gen Microbiol. 1984;130:1871-1882. |

| 12. | Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R. Principles and practice of infectious diseases. 6th ed. Churchill Livingstone: An Imprint of Elsevier 2005; 952. |

| 13. | Latsios G, Petrogiannopoulos C, Hartzoulakis G, Kondili L, Bethimouti K, Zaharof A. Liver abscess due to Bacillus cereus: a case report. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9:1234-1237. |

| 14. | Sakai C, Iuchi T, Ishii A, Kumagai K, Takagi T. Bacillus cereus brain abscesses occurring in a severely neutropenic patient: successful treatment with antimicrobial agents, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and surgical drainage. Intern Med. 2001;40:654-657. |

| 15. | Weber DJ, Saviteer SM, Rutala WA, Thomann CA. Clinical significance of Bacillus species isolated from blood cultures. South Med J. 1989;82:705-709. |

| 16. | Weber DJ, Saviteer SM, Rutala WA, Thomann CA. In vitro susceptibility of Bacillus spp. to selected antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:642-645. |

| 17. | Gascoigne AD, Richards J, Gould K, Gibson GJ. Successful treatment of Bacillus cereus infection with ciprofloxacin. Thorax. 1991;46:220-221. |

| 18. | Ozkocaman V, Ozcelik T, Ali R, Ozkalemkas F, Ozkan A, Ozakin C, Akalin H, Ursavas A, Coskun F, Ener B. Bacillus spp. among hospitalized patients with haematological malignancies: clinical features, epidemics and outcomes. J Hosp Infect. 2006;64:169-176. |

| 19. | Kemmerly SA, Pankey GA. Oral ciprofloxacin therapy for Bacillus cereus wound infection and bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:189. |

Peer reviewers: Akihito Tsubota, Assistant Professor, Institute of Clinical Medicine and Research, Jikei University School of Medicine, 163-1 Kashiwa-shita, Kashiwa, Chiba 277-8567, Japan; Dr. Stefan Wirth, Professor, Children’s Hospital, Heusnerstt. 40, Wuppertal 42349, Germany

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Stewart GJ E- Editor Ma WH