Published online Oct 21, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4919

Revised: August 21, 2009

Accepted: August 28, 2009

Published online: October 21, 2009

AIM: To investigate whether children should undergo surgery without a long period of fasting after feeding.

METHODS: Eighty children with inguinoscrotal disorders (aged 1-10 years) were studied prospectively. They were divided into eight groups that each contained 10 children who were fed normal liquid food (NLF) and a high-calorie diet (HCD) 2, 3, 4 and 5 h before surgery, in two doses at 6-h intervals. NLF was given to four groups and HCD to the other four. In all groups, glucose, prealbumin and cortisol levels in the blood were measured twice: just after oral feeding and just before the operation. After the establishment of adequate anesthesia, gastric residue liquid was measured with a syringe.

RESULTS: Blood glucose levels in all patients fed NLF and HCD were high, except in patients in the HCD-4 group. There was no significant difference in the blood prealbumin levels. There was a significant increase in the blood cortisol levels in the NLF-2 (14.4 ± 5.7), HCD-2 (13.2 ± 6.0), NLF-3 (10.9 ± 6.4), and HCD-5 (6.8 ± 5.7) groups (P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION: The stress of surgery may be tolerated by children when they are fed up to 2 h before elective surgery.

- Citation: Yurtcu M, Gunel E, Sahin TK, Sivrikaya A. Effects of fasting and preoperative feeding in children. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(39): 4919-4922

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i39/4919.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.4919

| Groups | Blood glucose (mg/dL) | Prealbumin (mg/dL) | Cortisol (μg/dL) | |||||

| PP(mean ± SD) | Fasting(mean ± SD) | P value(PP vs Fasting) | PP(mean ± SD) | Fasting(mean ± SD) | PP(mean ± SD) | Fasting(mean ± SD) | P value(PP vs Fasting) | |

| NLF-2 | 70.8 ± 9.6 | 133.2 ± 44.5a | 0.003 | 21.2 ± 3.4 | 27.1 ± 16.4 | 14.4 ± 5.7 | 22.6 ± 7.8 | 0.014 |

| HCD-2 | 69.0 ± 11.8 | 126.7 ± 29.5 | 0.000 | 19.8 ± 3.8 | 21.4 ± 4.8 | 13.2 ± 6.0 | 21.9 ± 5.9 | 0.008 |

| NLF-3 | 70.7 ± 12.2 | 119.7 ± 48.0 | 0.005 | 18.5 ± 2.8 | 18.4 ± 4.3 | 10.9 ± 6.4 | 18.1 ± 10.2 | 0.022 |

| HCD-3 | 64.5 ± 9.6 | 126.2 ± 25.9 | 0.000 | 19.2 ± 2.3 | 18.7 ± 1.4 | 14.9 ± 5.9 | 17.5 ± 4.1 | 0.219NS |

| NLF-4 | 64.4 ± 16.0 | 105.5 ± 24.2 | 0.002 | 14.9 ± 3.3 | 15.2 ± 3.9 | 14.4 ± 9.0 | 18.4 ± 7.9 | 0.316NS |

| HCD-4 | 71.7 ± 9.7 | 94.9 ± 41.4 | 0.120NS | 18.2 ± 2.4 | 17.4 ± 2.7 | 9.3 ± 5.7 | 13.9 ± 5.0 | 0.081NS |

| NLF-5 | 70.1 ± 11.0 | 89.7 ± 19.7 | 0.019 | 18.3 ± 4.9 | 18.7 ± 4.9 | 12.8 ± 5.2 | 14.4 ± 4.2 | 0.531NS |

| HCD-5 | 64.1 ± 8.8 | 83.4 ± 16.7 | 0.034 | 17.3 ± 10.0 | 16.2 ± 9.3 | 6.8 ± 5.7 | 15.0 ± 5.6 | 0.001 |

| P value (groups) | 0.570NS | 0.004 | 0.187NS | 0.158NS | 0.064NS | 0.027NS | ||

For many years, overnight fasting has been recommended before elective surgery. This fasting period is applied to reduce the risk of aspiration of stomach contents during anesthesia[1]. The routine use of perioperative oral dietary supplements in patients about to undergo gastrointestinal surgery confers no clinical or functional benefit[2].

However, this routine is now being questioned, because fasting causes discomfort and unnecessary problems with routine oral medication[3,4]. The free intake of water is allowed up to 3 h before surgery in children[5,6] and adults[7]. Thirst and anxiety are reduced in comparison with overnight fasting. Feeding with clear fluids does not increase gastric contents[7,8].

Although they do not diminish the risk of aspiration, clear liquids given enterally 2 h before surgery appear to pose no additional risk for aspiration of gastric contents in normal healthy children, and may provide some psychological benefit, as demonstrated by a decrease in irritability before induction of anesthesia[9]. It has been reported that a high-calorie diet (HCD) given enterally 2 h before surgery makes the surgery more comfortable[10,11].

Furthermore, Powell-Tuck et al[12] and Beier-Holgersen et al[13] have reported that early enteral feeding decreases postoperative complications, regulates wound improvement rapidly, decreases the cost of hospitalization, and increases quality of life and postoperative surgical success.

Recent studies have shown that perioperative insulin and glucose infusion maintains normal insulin sensitivity after surgery[14]. Prealbumin (transthyretin) level is used often as an indicator of protein status because of its relatively short half-life, high tryptophan content, high proportion of essential to nonessential amino acids, and small pool size. A sensitive acute phase reactant such as C-reactive protein always should be assayed along with prealbumin if levels are to be used to estimate nutritional status[15].

Although some studies have investigated the duration of fasting, to the best of our knowledge, there has been no research published about the metabolic changes in children fed normal liquid food (NLF) and an HCD, depending on the duration of fasting before an operation.

The aim of our study, therefore, was to compare NLF and HCD depending on the duration of fasting before surgery, and to decide whether children should undergo surgery without a long period of fasting after feeding them with an HCD.

This work was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2000) of the World Medical Association. The study was approved ethically by Selcuk University Meram Medical School (2005/058). All families provided informed written consent for their children.

The study population consisted of 80 patients (58 male; mean ± SD, 6.18 ± 1.25 years; range, 1-10 years). Blood samples were obtained from the patients by the same surgeon. The study was conducted as a randomized, single-blind clinical trial. The children included in the study were outpatients and they had inguinoscrotal disorders without any additional abnormality. Sixty-two (77.5%) patients who had inguinal hernias underwent high ligation (Ferguson procedure) and 18 (22.5%) who had undescended testes underwent orchidopexy. All patients were admitted on the day of surgery or underwent surgery as outpatients. Tracheal intubation was planned in all cases. General anesthesia was used. Patients taking medication or who had a disease known to delay gastric emptying or increase acid production were excluded.

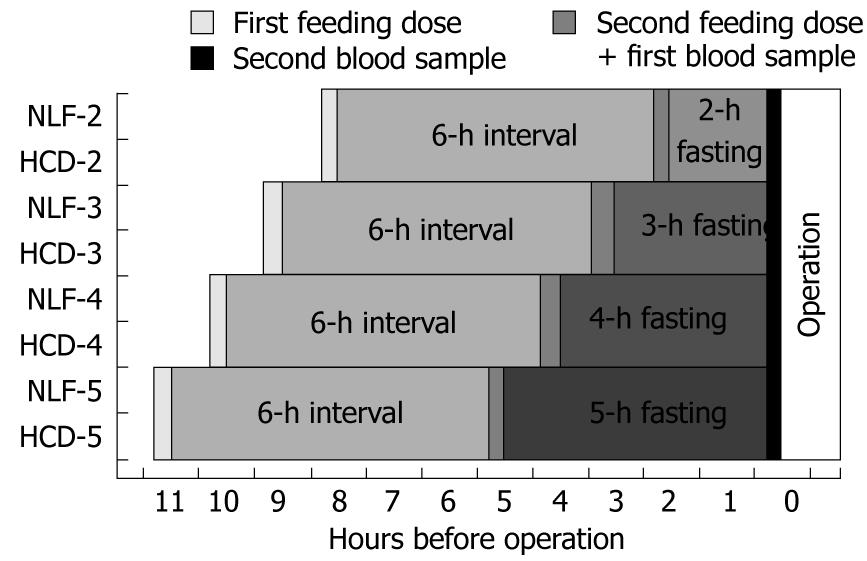

The patients were divided into eight groups, each containing 10 patients who were fed NLF and an HCD 2, 3, 4 and 5 h before surgery. NLF was given to four groups and HCD to the other four (Figure 1). The food and liquid requirements of the children, which consisted of 10 mL/kg, were given orally in two doses at 6-h intervals, after calculating their carbohydrate, protein, lipid, and electrolyte needs according to body weight. Then, they were fasted for 2, 3, 4 and 5 h preoperatively. After the establishment of an adequate and stable level of anesthesia, a 14 or 16 Fr Levin multi-orificed gastric tube was passed orally into the stomach by the same investigator, who was unaware of the patient’s fasting status, to determine whether there was any residue in the stomach before surgery. After confirmation of the gastric tube’s position by auscultation, gastric fluid contents were obtained through the tube by gentle aspiration with a 60-mL syringe in several positions, with the patient tilted head-up, head-down, to the right, and to the left. Gastric residue liquid was measured using this syringe.

Blood samples were obtained twice from the patients in all groups (Figure 1), when oral feeding was stopped and just before the operation (before the induction of anesthesia), to measure the values of blood glucose, prealbumin and cortisol. After all the blood samples were taken, blood glucose levels were determined in a Beckman Coulter Unicel DXC 800 Synchron Clinical System autoanalyzer (Beckman Coulter, Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA) using a Beckman Coulter test kit (catalog no: T709005). Prealbumin levels were determined using a Beckman Coulter test kit (catalog no: M605268) in a Beckman Array Protein System autoanalyzer. Cortisol levels were determined using a Beckman Coulter test kit (catalog no: 230) in Unicel DXI-800 Access Immunoassay System autoanalyzer (Beckman Coulter Inc. Immunodiagnostic Development Center, Chaska, USA).

Power was calculated as 100% with a sample size of 10 patients in each group. All data were presented as mean ± SD for biochemical analysis. Two-way repeated measures of ANOVA were used to compare postprandial (PP) and starvation values for each parameter in the eight groups. Post-hoc tests were used to identify the origin of the difference when a significant difference was identified. For this purpose, Bonferroni-corrected one-way ANOVA and Tukey-HSD test were used to identify whether there was a difference among the groups during the PP and fasting periods. Moreover, Student’s paired t test was used to compare the PP and starvation values in each dependent group. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. However, P < 0.025 was considered statistically significant when Bonferroni correction was made. For all calculations, SPSS version 13.0 was used, and for calculation of power PASS version 08.07 was used.

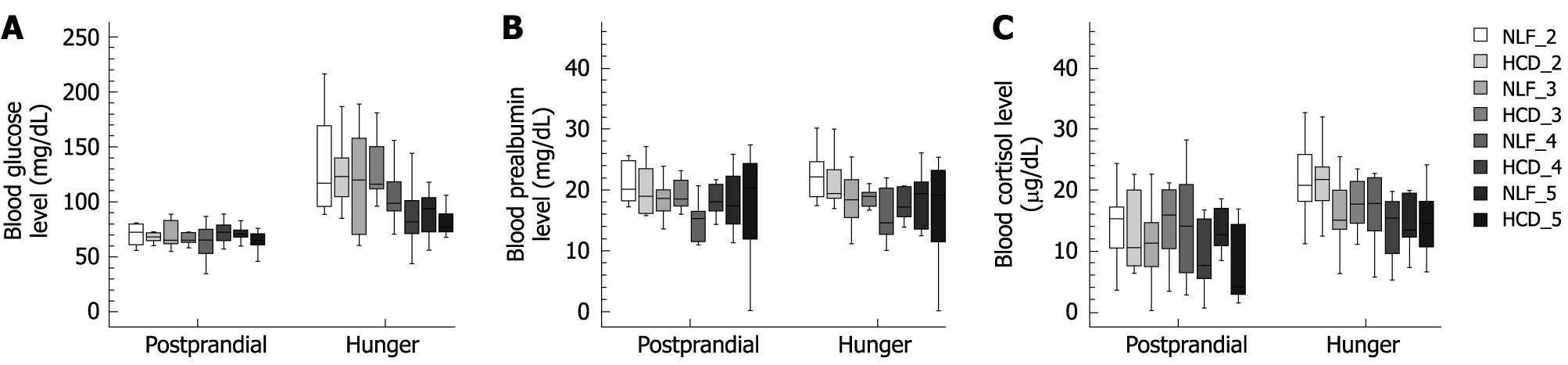

PP blood glucose levels within and between groups were significantly lower compared to the fasting blood glucose levels, except for HCD-4. There was no significant difference regarding PP blood glucose (P = 0.570), but there was a significant increase in the fasting values of blood glucose in the NLF-2 group when compared with the HCD-5 group (P = 0.004) (Table 1 and Figure 2A).

There was no significant difference between or within the groups (P = 0.162) regarding blood prealbumin (Table 1 and Figure 2B).

PP blood cortisol levels in the NLF-2, HCD-2, NLF-3, NLF-5 and HCD-5 groups were significantly lower compared to fasting blood glucose levels (Table 1 and Figure 2C). The stomach residue liquids of all patients were at tolerable levels (1-2 mL). All anesthesia induction was uneventful, and no patient suffered from coughing, laryngospasm, or vomiting. There was no problem regarding the outcomes of surgery or wound healing.

Preoperative fasting has been applied before elective surgery to prevent the risk of aspiration of stomach contents during anesthesia[1], but no study has examined whether there were negative effects of an HCD on the effects of duration of fasting and preoperative feeding on metabolic changes and anesthesia in children[3,4].

The ingestion of unlimited clear fluids by healthy 2-12-year-old children up to 2 h before elective surgery does not affect gastric contents[6]. In addition, there is no correlation between the fasting interval and gastric fluid pH or volume, and 2 mL/kg of water may be administered to healthy, non-premedicated children 2 h before surgery, without decreasing gastric fluid pH or increasing gastric fluid volume compared to those fasting for up to 6 h[5]. Drinking clear liquids up to 2 h before anesthesia induction is unlikely to affect substantially the volume of gastric fluid contents or the percentage of patients with gastric fluid pH ≤ 2.5. Clear lipids appear to add no additional risk for aspiration of gastric contents in normal healthy children, and may provide some psychological benefit, as demonstrated by a decrease in irritability before induction of anesthesia[9]. Partial feeding in the immediate (up to 2 h before premedication) preoperative period may become routine in the future[1].

The values of blood glucose and insulin are known to be increased significantly 40 min after ingestion of a carbohydrate-rich drink[1]. Perioperative glucose and insulin infusions minimize the endocrine stress response and normalize postoperative insulin sensitivity and substrate utilization[14]. To achieve standardization in our study, the food and liquid requirements of the patients were given in two doses at 6-h intervals, and blood samples were obtained from all groups twice before surgery. It is novel to evaluate metabolic changes in children fed NLF and an HCD, depending on the duration of fasting before surgery. In the present study, blood glucose levels increased and stomach residue liquids were at a tolerable level in all patients fed NLF and an HCD. These results indicate that children can tolerate the stress of surgery when they are fed until 2 h before surgery, because there was no difference regarding stomach residue and metabolic changes among patients that underwent surgery after fasting for short and long periods.

In conclusion, there is no need for more than 2 h of fasting before inguinoscrotal region surgery. Further studies in surgical patients should help to substantiate the safety and clinical benefits of this new concept.

Preoperative fasting has been applied before elective surgery to prevent the risk of aspiration of stomach contents during anesthesia, but no study has examined whether there are negative effects of a high calorie diet (HCD) on the effects of duration of fasting and preoperative feeding on metabolic changes and anesthesia in children.

Children can tolerate the stress of surgery when they are fed with normal liquid food (NLF) and HCD until 2 h before surgery, because there was no difference regarding stomach residue and metabolic changes among patients that underwent surgery after fasting for short and long periods.

For many years, overnight fasting has been recommended before elective surgery. This fasting period is applied to reduce the risk of aspiration of stomach contents during anesthesia. The routine use of perioperative oral dietary supplements in patients about to undergo gastrointestinal surgery confers no clinical or functional benefit. However, this routine is now being questioned, because fasting causes discomfort and unnecessary problems with routine oral medication. It is novel to evaluate metabolic changes in children fed NLF and an HCD, depending on the duration of fasting before surgery. In the present study, blood glucose levels increased and stomach residue liquids were at a tolerable level in all patients fed NLF and an HCD. These results indicated that children can tolerate the stress of surgery when they are fed until 2 h before surgery, because there was no difference regarding stomach residue and metabolic changes among patients that underwent surgery after fasting for short and long periods.

The study results suggest that there is no need for more than 2 h of fasting before inguinoscrotal region surgery in preventing the risk of aspiration of stomach contents during anesthesia.

Glucose infusions minimize the endocrine stress response. Prealbumin (transthyretin) level is used as an indicator of protein status because of its relatively short half-life, high tryptophan content, high proportion of essential to nonessential amino acids, and small pool size. Cortisol preserves the completeness of the cell membrane, inhibits increased capillary permeability, and has an anti-inflammatory effect.

This is an interesting paper, well-written and well-documented. The analysis of data has been done very carefully and the results are convincing.

| 1. | Nygren J, Thorell A, Jacobsson H, Larsson S, Schnell PO, Hylén L, Ljungqvist O. Preoperative gastric emptying. Effects of anxiety and oral carbohydrate administration. Ann Surg. 1995;222:728-734. |

| 3. | Maltby JR, Lewis P, Martin A, Sutheriand LR. Gastric fluid volume and pH in elective patients following unrestricted oral fluid until three hours before surgery. Can J Anaesth. 1991;38:425-429. |

| 4. | Miller M, Wishart HY, Nimmo WS. Gastric contents at induction of anaesthesia. Is a 4-hour fast necessary? Br J Anaesth. 1983;55:1185-1188. |

| 5. | Crawford M, Lerman J, Christensen S, Farrow-Gillespie A. Effects of duration of fasting on gastric fluid pH and volume in healthy children. Anesth Analg. 1990;71:400-403. |

| 6. | Splinter WM, Schaefer JD. Unlimited clear fluid ingestion two hours before surgery in children does not affect volume or pH of stomach contents. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1990;18:522-526. |

| 7. | Phillips S, Hutchinson S, Davidson T. Preoperative drinking does not affect gastric contents. Br J Anaesth. 1993;70:6-9. |

| 8. | Read MS, Vaughan RS. Allowing pre-operative patients to drink: effects on patients' safety and comfort of unlimited oral water until 2 hours before anaesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1991;35:591-595. |

| 9. | Schreiner MS, Triebwasser A, Keon TP. Ingestion of liquids compared with preoperative fasting in pediatric outpatients. Anesthesiology. 1990;72:593-597. |

| 10. | Silk DB, Green CJ. Perioperative nutrition: parenteral versus enteral. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 1998;1:21-27. |

| 11. | Lanoir D, Chambrier C, Vergnon P, Meynaud-Kraemer L, Wilkinson J, Mcpherson K, Bouletreau P, Colin C. Perioperative artificial nutrition in elective surgery: an impact study of French guidelines. Clin Nutr. 1998;17:153-157. |

| 12. | Powell-Tuck J. Perioperative nutritional support: does it reduce hospital complications or shorten convalescence? Gut. 2000;46:749-750. |

| 13. | Beier-Holgersen R, Boesby S. Influence of postoperative enteral nutrition on postsurgical infections. Gut. 1996;39:833-835. |

| 14. | Nygren JO, Thorell A, Soop M, Efendic S, Brismar K, Karpe F, Nair KS, Ljungqvist O. Perioperative insulin and glucose infusion maintains normal insulin sensitivity after surgery. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:E140-E148. |

| 15. | Johnson AM. Amino acids, peptides, and proteins. Tietz textbook of clinical chemistry and molecular diagnostics. Missouri: Elsevier Saunders 2006; 533-554. |

Peer reviewer: Luigi Bonavina, Professor, Department of Surgery, Policlinico San Donato, University of Milano, via Morandi 30, Milano 20097, Italy

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Lin YP