Published online Sep 21, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4461

Revised: August 20, 2009

Accepted: August 27, 2009

Published online: September 21, 2009

Pneumatic dilation (PD) is considered to be a safe and effective first line therapy for achalasia. The major adverse event caused by PD is esophageal perforation but an immediate gastrografin test may not always detect a perforation. It has been reported that delayed management of perforation for more than 24 h is associated with high mortality. Surgery is the treatment of choice within 24 h, but the management of delayed perforation remains controversial. Hereby, we report a delayed presentation of intrathoracic esophageal perforation following PD in a 48-year-old woman who suffered from achalasia. She completely recovered after intensive medical care. A review of the literature is also discussed.

- Citation: Lin MT, Tai WC, Chiu KW, Chou YP, Tsai MC, Hu TH, Lee CM, Changchien CS, Chuah SK. Delayed presentation of intrathoracic esophageal perforation after pneumatic dilation for achalasia. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(35): 4461-4463

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i35/4461.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.4461

Esophageal achalasia is an inflammatory disease characterized by esophageal aperistalsis and failure of complete LES relaxation due to loss of the inhibitory intrinsic neurons of the esophageal myenteric plexus[1,2]. Pneumatic dilation (PD) is considered to be the first line therapy for achalasia[3,4]. Esophageal perforation could be a hazardous event if left untreated after PD[5]. Usually, gastrografin is ingested immediately after each PD to detect extravasations which imply perforation.

However, on rare occasions, immediate gastrografin ingestion may not always detect a perforation which could become clinically evident several hours later resulting in a delayed presentation (more than 24 h)[6]. Hereby we report our experience in treating an achalasia patient who suffered from delayed clinical presentation of intrathoracic esophageal perforation after PD but healed after intensive medical care.

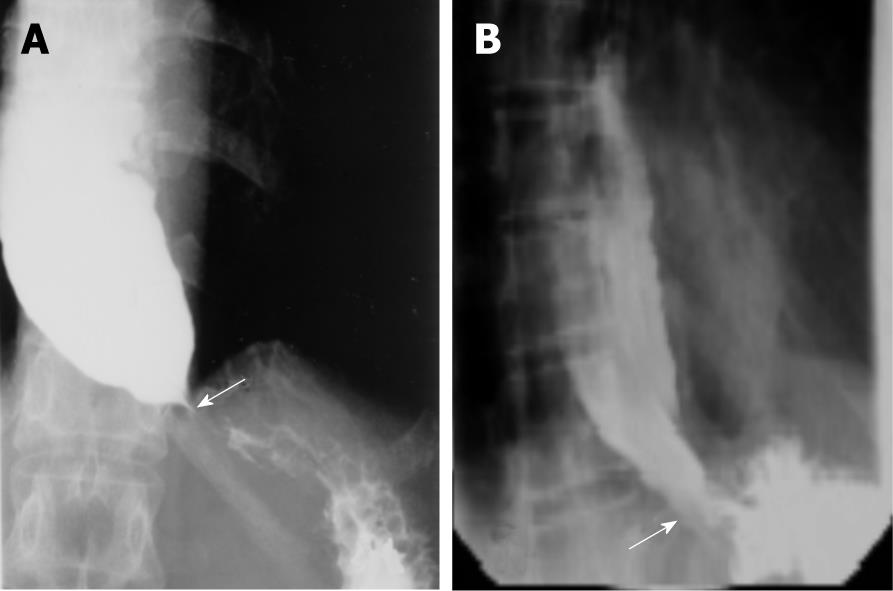

The 48-year-old female, who had a history of surgery for uterine myoma status for 2 years, was referred to our hospital due to esophageal stenosis. She suffered from progressive symptoms of dysphagia for liquid and solid foods, chest pain and food regurgitation for the previous 6 mo. She also complained of gradual body weight loss of 5 kg during this period. She had no family history of gastrointestinal cancer. Physical examination revealed an unhealthy, conscious woman with stable vital signs. The laboratory data were as follows: white blood cell count: 4.1 × 103 cells/μL (normal 3.5-11 cells/μL), hemoglobin: 10.5 g/dL (normal 12-16 g/dL), hematocrit: 32% (normal 36%-46%), mean corpuscular volume: 69.3 μm3 (normal 80-100 μm3), platelet count: 18.8 × 103/μL (normal 15-40 × 103/μL), sodium: 142 mmol/L (134-148 mmol/L), potassium: 3.7 mmol/L (normal 3.0-4.8 mmol/L). A barium esophagogram revealed a dilated distal esophageal lumen with food retention at a narrowing of the gastroesophageal junction (Figure 1A). Achalasia was confirmed using manometric findings of esophageal aperistalsis and incomplete relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter during wet swallowing. The residual pressure was about 10 mmHg but the basal lower esophageal sphincter pressure was about 45 mmHg. Achalasia caused by tumors was excluded by computed tomography (CT). The patient received PD with a 3-cm “Regiflex” dilator. Routine gastrografin ingestion showed no sign of immediate leakage of contrast (Figure 1B). She was fine after PD with only mild chest pain and asked to be scheduled for discharge. Her vital signs remained stable in the next 24 h following PD.

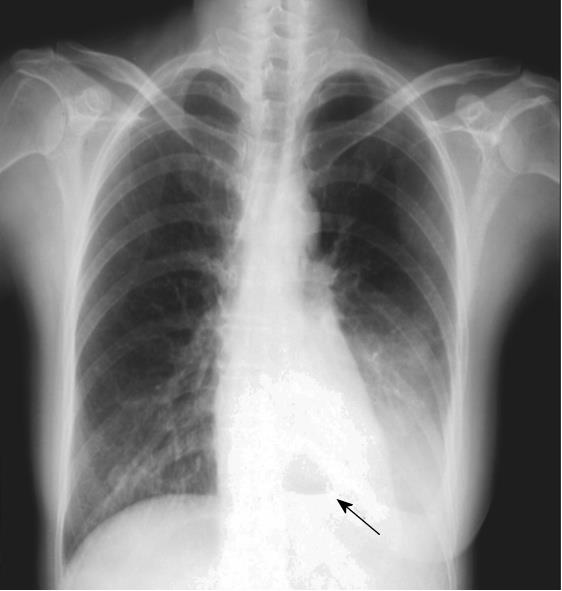

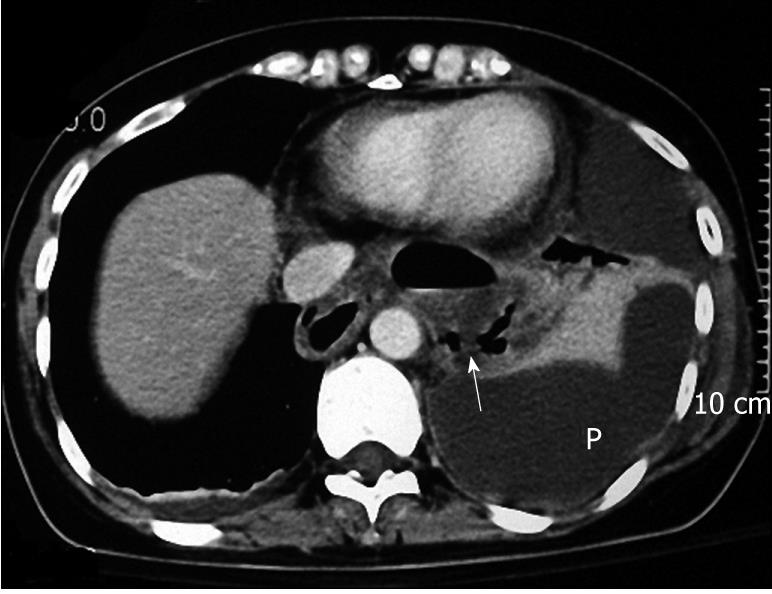

Unfortunately, severe chest pain occurred 6 h later with fever up to 38°C. Chest radiograph revealed left side pleural effusion, left lower lobe consolidation and air-fluid level over retrocardiac region air fluid level over the retrosternal area (Figure 2). The chest CT revealed esophageal dilatation suspicious of rupture of the lower esophagus with prominent pleural effusion and fluid collection over the middle and lower mediastinum (Figure 3). Due to rapid progression of the dyspneic condition and high fever to 40°C, a chest drainage tube was placed immediately. Intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics were also given immediately. She was then transferred to the cardiovascular surgery intensive care unit. She refused to receive any surgical intervention. Total parenteral nutrition was given via the venous route to ensure an appropriate nutrition supply. Fortunately, her condition improved gradually 2 wk later. A barium esophagogram revealed a dilated esophagus without any contrast leakage and absence of bird-beak signs. She was discharged safely another 2 wk later. She remained in clinical remission status 8 years after PD.

Esophageal perforation is a relatively uncommon complication even though many diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in daily practice require the passing of instruments through the esophagus, such as endoscope-guided PD for this lady who suffered from esophageal achalasia. The signs and symptoms of esophageal perforation are non-specific but may include pain, fever, dyspnea, vomiting, crepitus, and shock[6]. Despite prompt treatment and improved management, the mortality of esophageal perforation is still significant[7]. The esophagus lacks a serosal layer and the adventitia of the esophagus is contiguous with the connective tissue of the mediastinum. As a result, esophageal perforation allows the leakage of food residues, saliva, oropharyngeal bacteria and digestive enzymes into the mediastinum and chest cavity. Severe adverse events such as mediastinitis, pleural emphysema, empyema, or subdiaphragmatic abscess may occur rapidly in delayed diagnosed and managed patients[8]. The impact of delayed recognition is decreasing despite the high incidence of complications. Reeder and colleagues reported a 29% mortality rate following late diagnosis[9]. The most important predictor of treatment outcome depends on the time interval from perforation to treatment. It has been reported that delayed management of perforation for more than 24 h is associated with a 3-5 fold increase in mortality.

The diagnosis of delayed presentation of esophageal rupture remains a clinical challenge because of the non-specific findings of this rare clinical condition. Ingestion of water-soluble gastrografin immediately after each PD is a standard examination to avoid possible extravasation of barium-containing agents that may cause serious mediastinitis[10]. Imaging studies provide a reliable way to make a definite diagnosis of esophageal perforation. Contrast leakage on imaging studies suggests leakage of gastric juice and other substance into the mediastinum and causes the inflammatory process. Unfortunately, an immediate gastrografin test may not always detect a perforation which could become clinically evident several hours later and this must be kept in mind. Absence of contrast leakage may suggest a small or a sealed-off perforation. This may result in the tricky delayed clinical presentations following dilations. This explains the initial stable subjective and objective conditions that occurred in our patient following PD. Buecker and colleagues suggest that a negative gastrografin study should be followed-up with a barium study to increase sensitivity[11] but then the patient may be at risk of severe mediastinitis.

The management of esophageal perforations includes fluid resuscitation, antibiotics, gastric decompression, and surgery. Broad-spectrum antibiotics that cover Gram-positive, Gram-negative, and anaerobic organisms should be started and tailored to culture results[7]. Surgery is the treatment of choice within 24 h, but the management of delayed perforation remains controversial. Quintana and colleagues reported the mortality rate in patients with prompt surgical treatment ranged from 0% to 34%, and those without immediate treatment 68.7%-75%[12].

However, Younes and colleagues advocated that patients with mild fever, absence of shock and sepsis might be considered for conservative management[13]. There was no difference in mortality rate between surgery and medical treatment in these two publications[12,13]. The other theoretical issue is whether the perforation would heal in the presence of distal obstruction, which this patient potentially had before PD as a result of her underlying achalasia; however the follow-up esophagogram revealed patency of the distal lumen. All the above favorable factors were probably the main reasons for the recovery of our patient despite her refusal of surgery. Therefore, intensive non-surgical treatment may be another option for treatment with a favorable outcome in selected patients with a good general health status.

The sizes of the balloons and the techniques of the procedure are relevant to esophageal perforation in treating achalasia under the guidance of a fluoroscope or endoscope[3,14-16]. Graded PD with a 30 mm diameter and slower rate of balloon inflation is an effective and safe initial method of therapy for achalasia. The potential danger in increased risk of perforation is likely to interfere with the effect of dilation toward the side of the endoscope, and this can be compromising and lead to a decrease in overall efficacy of the procedure and the possibility of generating an unequal radial force on the sphincter[17].

In summary, early identification of a delayed presentation of intrathoracic esophageal perforation requires premeditated consideration and is crucial for a favorable outcome. However, an immediate contrast study may not always detect a perforation which can become clinically evident several hours later. Therefore, close observation of clinical symptoms and signs such as severe chest pain and fever implying potential perforations is mandatory after PD. Surgery is the treatment of choice within 24 h. Intensive non-surgical treatment could be another option for treatment with a favorable outcome in selected patients with a good general health status.

| 1. | Park W, Vaezi MF. Etiology and pathogenesis of achalasia: the current understanding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1404-1414. |

| 2. | Paterson WG. Etiology and pathogenesis of achalasia. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2001;11:249-266, vi. |

| 3. | Chuah SK, Hu TH, Wu KL, Kuo CM, Fong TV, Lee CM, Changchien CS. Endoscope-guided pneumatic dilatation of esophageal achalasia without fluoroscopy is another safe and effective treatment option: a report of Taiwan. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2008;18:8-12. |

| 4. | Lake JM, Wong RK. Review article: the management of achalasia - a comparison of different treatment modalities. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:909-918. |

| 5. | Kiev J, Amendola M, Bouhaidar D, Sandhu BS, Zhao X, Maher J. A management algorithm for esophageal perforation. Am J Surg. 2007;194:103-106. |

| 6. | Bernard AW, Ben-David K, Pritts T. Delayed presentation of thoracic esophageal perforation after blunt trauma. J Emerg Med. 2008;34:49-53. |

| 7. | Zhou JH, Gong TQ, Jiang YG, Wang RW, Zhao YP, Tan QY, Ma Z, Lin YD, Deng B. Management of delayed intrathoracic esophageal perforation with modified intraluminal esophageal stent. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22:434-438. |

| 8. | Altorjay A, Kiss J, Vörös A, Szirányi E. The role of esophagectomy in the management of esophageal perforations. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65:1433-1436. |

| 9. | Reeder LB, DeFilippi VJ, Ferguson MK. Current results of therapy for esophageal perforation. Am J Surg. 1995;169:615-617. |

| 10. | White RK, Morris DM. Diagnosis and management of esophageal perforations. Am Surg. 1992;58:112-119. |

| 11. | Buecker A, Wein BB, Neuerburg JM, Guenther RW. Esophageal perforation: comparison of use of aqueous and barium-containing contrast media. Radiology. 1997;202:683-686. |

| 12. | Quintana R, Bartley TD, Wheat MW Jr. Esophageal perforation. Analysis of 10 cases. Ann Thorac Surg. 1970;10:45-53. |

| 13. | Younes Z, Johnson DA. The spectrum of spontaneous and iatrogenic esophageal injury: perforations, Mallory-Weiss tears, and hematomas. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;29:306-317. |

| 14. | Dobrucali A, Erzin Y, Tuncer M, Dirican A. Long-term results of graded pneumatic dilatation under endoscopic guidance in patients with primary esophageal achalasia. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:3322-3327. |

| 15. | Chuah SK, Hu TH, Wu KL, Hsu PI, Tai WC, Chiu YC, Lee CM, Changchien CS. Clinical remission in endoscope-guided pneumatic dilation for the treatment of esophageal achalasia: 7-year follow-up results of a prospective investigation. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:862-867. |

| 16. | Rabinovici R, Katz E, Goldin E, Kluger Y, Ayalon A. The danger of high compliance balloons for esophageal dilatation in achalasia. Endoscopy. 1990;22:63-64. |

| 17. | Mikaeli J, Bishehsari F, Montazeri G, Yaghoobi M, Malekzadeh R. Pneumatic balloon dilatation in achalasia: a prospective comparison of safety and efficacy with different balloon diameters. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:431-436. |

Peer reviewer: Luigi Bonavina, Professor, Department of Surgery, Policlinico San Donato, University of Milano, via Morandi 30, Milano 20097, Italy

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Zheng XM