Published online Sep 7, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4209

Revised: August 4, 2009

Accepted: August 11, 2009

Published online: September 7, 2009

Metastatic penile carcinoma is rare and usually originates from genitourinary tumors. The presenting symptoms or signs have been described as nonspecific except for priapism. Rectal adenocarcinoma is a very unusual source of metastatic penile carcinoma. We report a case of metastatic penile carcinoma that originated from the rectum. Symptomatic improvement occurred with palliative radiotherapy.

- Citation: Park JC, Lee WH, Kang MK, Park SY. Priapism secondary to penile metastasis of rectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(33): 4209-4211

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i33/4209.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.4209

Metastatic tumors of the penis are rare despite an abundant blood supply to the penis. Approximately 300 cases have been reported in the clinical literature[1]. Primary sites of origin are the bladder (33%), prostate (30%), colon (17%) and kidney (7%)[2]. Extra-pelvic sites including the lung, pancreas, stomach, esophagus, melanoma and testis have been noted[3-6]. Fewer than 60 cases of penile metastasis from colon cancer have been reported. Penile metastasis has been a part of more widespread disease in about 90% of reported cases[7]. We report a case of a painful penile metastasis as a manifestation of rectal cancer dissemination that was improved by the use of palliative radiotherapy.

A 43-year-old man was admitted to our clinic with a penile erection and pain. Two years earlier, the patient had undergone abdominoperineal resection for adenocarcinoma of the rectum, followed by adjuvant chemoradiotherapy with capecitabine. Postoperative pathology revealed a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma and pathological T3 tumor with metastases in 15 out of 37 regional lymph nodes. Thirteen months earlier, recurrence of rectal cancer was detected in the abdominal para-aortic nodes. Various palliative chemotherapeutic agents were administered for 11 mo and the patient received no further treatment. One month earlier, penile erection and pain developed.

Physical examination showed no visible skin lesions, but multiple palpable hard nodules were present over the penile shaft. Tenderness developed following palpation of the penis.

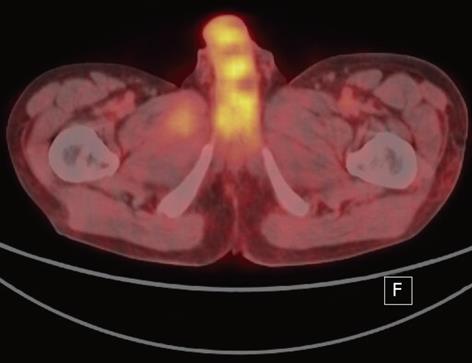

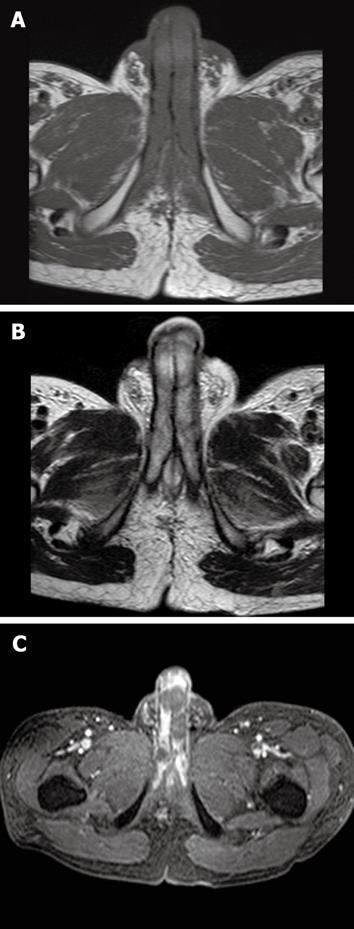

The penile lesions had multifocal, irregular-shaped, low-density areas as depicted on pelvic computed tomography (CT) images, and these lesions had increased in size and number as compared with previous CT images obtained 3 mo previously (Figure 1). Positron emission tomography (PET) showed low 18F- fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the lesions (Figure 2). Penile magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed low to iso-intensity signals as compared with the surrounding corpus cavernosum on an axial T1-weighted image, low to intermediate signal intensity on an axial T2-weighted image, and the presence of non-enhanced lesions on a gadolinium-enhanced image (Figure 3). Other sites of metastasis were noted in several para-aortic lymph nodes, lung and vertebral body of the L2 spine.

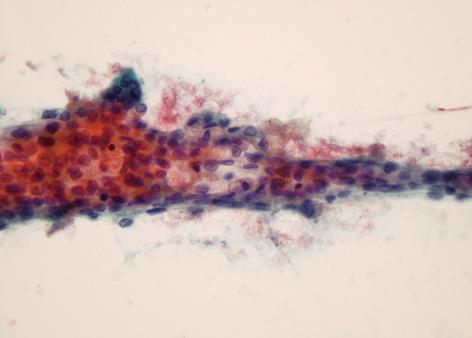

Fine needle aspiration of the nodules was performed and histological examination showed nests of acinar-like cells with cytological atypia, consistent with metastatic adenocarcinoma from primary rectal cancer (Figure 4).

Intravenous morphine infusion and spinal nerve block were given for control of penile pain, but were ineffective. Other treatment options were required but the patient was in a chemotherapy refractory and systemic disseminated state. As a result of poor performance status, the patient was not allowed to undergo palliative partial or total penectomy. We offered the patient the option of undergoing palliative external beam radiation (2600 cGy, 13 fractions), which was preformed successfully. Penile pain was relieved and the patient was discharged from the hospital.

The reason why the penis is a rare site for metastasis despite rich vascularization is not clear. Various mechanisms for penile metastasis have been suggested. These include retrograde venous spread, retrograde lymphatic spread, arterial embolism and local direct extension[3]. Currently, a route that involves retrograde venous spread from the pudendal into the dorsal venous system of the penis is considered as the most likely mechanism.

Presenting symptoms and signs in order of frequency are malignant priapism (40%), urinary retention, penile nodules, ulceration, perineal pain, edema, generalized swelling, broad infiltrative enlargement, dysuria and hematuria[1]. Penile metastasis must be differentiated from primary penile cancer, chancre, chancroid, non-tumorous priapism, Peyronie’s disease, tuberculosis and other inflammatory and suppurative diseases[8]. The corpus cavernosum is usually the site of involvement of metastatic penile carcinoma. The glans penis and corpus spongiosum are involved rarely.

Penile lesions require an excisional or fine-needle aspiration biopsy for pathological confirmation. However, radiological evaluations such as CT, MRI and PET are useful noninvasive methods for the evaluation of lesions[3,9].

Penile metastases typically manifest as multiple discrete masses in the corpus cavernosum. Noninvasive modalities such as CT, MRI and PET are being used increasingly. CT has been used in the evaluation of penile lesions. Due to only single-plane imaging, its use is limited and it may not detect penile metastasis[9]. MRI is a most reliable alternative for diagnosis and assessing the extent of penile metastasis, with its multi-plane imaging and superior soft tissue contrast. These masses have low signal intensity relative to normal corporal tissues in T1-weighted images, and low or high signal intensity in T2-weighted images[9-11]. PET is also useful for detection of clinically silent metastatic sites in hypermetabolic cancer[5,11].

The treatment plan depends on the performance status and primary cancer state of the patient. Treatment modalities include local excision, penectomy, chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Most patients with penile metastasis already have widely disseminated disease, and > 80% of the patients will die within 6 mo, irrespective of the primary tumor and the treatment method, making palliative noninvasive treatment advisable.

In conclusion, we report a case of painful priapism secondary to penile metastasis of rectal cancer, which was improved by palliative radiotherapy. Most patients with metastatic penile carcinoma have developed systemic dissemination and early detection, precise diagnosis and noninvasive treatment are required for improvement of quality of life.

| 1. | Hizli F, Berkmen F. Penile metastasis from other malignancies. A study of ten cases and review of the literature. Urol Int. 2006;76:118-121. |

| 2. | Burgers JK, Badalament RA, Drago JR. Penile cancer. Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and staging. Urol Clin North Am. 1992;19:247-256. |

| 3. | Cherian J, Rajan S, Thwaini A, Elmasry Y, Shah T, Puri R. Secondary penile tumours revisited. Int Semin Surg Oncol. 2006;3:33. |

| 4. | Ahn TY, Choi EH, Kim KS. Secondary penile carcinoma originated from pancreas. J Korean Med Sci. 1997;12:67-69. |

| 5. | Pai A, Sonawane S, Purandare NC, Rangarajan V, Ramadwar M, Pramesh CS, Mistry RC. Penile metastasis from esophageal squamous carcinoma after curative resection. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;14:238-241. |

| 6. | Kurul S, Aykan F, Tas F. Penile metastasis of cutaneous malignant melanoma: a true hematogenous spread?: Case report and review of the literature. Melanoma Res. 2006;16:259-261. |

| 7. | Dubocq FM, Tefilli MV, Grignon DJ, Pontes JE, Dhabuwala CB. High flow malignant priapism with isolated metastasis to the corpora cavernosa. Urology. 1998;51:324-326. |

| 8. | Abeshouse BS, Abeshouse GA. Metastatic tumors of the penis: a review of the literature and a report of two cases. J Urol. 1961;86:99-112. |

| 9. | Lau TN, Wakeley CJ, Goddard P. Magnetic resonance imaging of penile metastases: a report on five cases. Australas Radiol. 1999;43:378-381. |

| 10. | Kendi T, Batislam E, Basar MM, Yilmaz E, Altinok D, Basar H. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in penile metastases of extragenitourinary cancers. Int Urol Nephrol. 2006;38:105-109. |

| 11. | Singh AK, Gonzalez-Torrez P, Kaewlai R, Tabatabaei S, Harisinghani MG. Imaging of penile neoplasm. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2007;28:287-296. |