Published online Aug 28, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4009

Revised: July 10, 2009

Accepted: July 17, 2009

Published online: August 28, 2009

AIM: To evaluate the clinical characteristics of splenic marginal-zone lymphoma (SMZL) following antigen expression and the influence of therapeutic approaches on clinical outcome and overall survival (OS).

METHODS: A total of 30 patients with typical histological and immunohistochemical SMZL patterns were examined. Splenectomy plus chemotherapy was applied in 20 patients, while splenectomy as a single treatment-option was performed in 10 patients. Prognostic factor and overall survival rate were analyzed.

RESULTS: Complete remission (CR) was achieved in 20 (66.7%), partial remission (PR) in seven (23.3%), and lethal outcome due to disease progression occurred in three (10.0%) patients. Median survival of patients with a splenectomy was 93.0 mo and for patients with splenectomy plus chemotherapy it was 107.5 mo (Log rank = 0.056, P > 0.05). Time from onset of first symptoms to the beginning of the treatment (mean 9.4 mo) was influenced by spleen dimensions, as measured by computerized tomography and ultra-sound (t = 2.558, P = 0.018). Strong positivity (+++) of CD20 antigen expression in splenic tissue had a positive influence on OS (Log rank = 5.244, P < 0.05). The analysis of factors interfering with survival (by the Kaplan-Meier method) revealed that gender, general symptoms, clinical stage, and spleen infiltration type (nodular vs diffuse) had no significant (P > 0.05) effects on the OS. The expression of other antigens (immunohistochemistry) also had no effect on survival-rate, as measured by a χ2 test (P > 0.05).

CONCLUSION: Initial splenectomy combined with chemotherapy has been shown to be beneficial due to its advanced remission rate/duration; however, a larger controlled clinical study is required to confirm our findings.

- Citation: Milosevic R, Todorovic M, Balint B, Jevtic M, Krstic M, Ristanovic E, Antonijevic N, Pavlovic M, Perunicic M, Petrovic M, Mihaljevic B. Splenectomy with chemotherapy vs surgery alone as initial treatment for splenic marginal zone lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(32): 4009-4015

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i32/4009.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.4009

Splenic marginal-zone lymphoma (SMZL) is an indolent B-cell lymphoma, generally presented with splenomegaly, and frequent involvement of the bone marrow and peripheral blood. The typical immunophenotypic profile is: IgM+, IgD+/-, cytoplasmic Ig-/+, pan B antigens+, CD5-, CD10-, CD23-, CD43-/+, and cyclin D1-. It is characterized by micronodular infiltration of the spleen with marginal-zone differentiation[1–4]. An SMZL variant with villous lymphocytes (SMZL + VL) has been previously described as “splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes”, and included into the FAB classification of chronic B-cell leukemias[5]. Lymphomas of the marginal zone are recognized as separate clinical phenomena amongst B-cell NHL in the REAL classification. Thus, SMZL was divided from other marginal zone lymphomas, such as mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma or nodal B-type marginal zone lymphoma, and accepted by WHO classification in 2001 as a distinct clinical and pathohistological (PH) entity[6–9]. According to more recent data, SMZL and SMZL with or without villous lymphocytes (SMZL ± VL) are two phases (tissue and leukemic) of the same disease[1011].

Typical genetic abnormalities in SMZL are deletions at 7q22-7q32[8]. The majority of SMZL patients have good long-time survival. Standard prognostic factors cannot differentiate patients into groups with poor or high-quality clinical outcomes. However, several immune-mediated events, such as hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia, as well as the presence of the serum monoclonal component, could be predictive factors for survival-rate. Splenectomy is considered the first-line treatment for SMZL patients[1213]. Even if this therapy results just in partial remission (PR), surgery-response is usually sufficient to correct (pan) cytopenia and also to improve the patient’s quality of life and overall survival-rate. The presence of SMZL in peripheral lymph nodes and extranodal locations is uncommon. Thus, the spleen is considered the site of lymphoma origin, even if there were regional enlargements of the lymph nodes[9–11]. The frequency of mutation in the 5' non-coding region of the bcl-6 gene has been used as a marker of germinal center derivation, which might be used to establish the molecular heterogeneity[14–16]. Therefore, SMZL is a primary disease of the spleen, with subsequent bone marrow (BM) and peripheral blood (PB) involvement[17–19]. The diagnosis is based on the spleen PH, in accordance with clinical data. Incorporation of immunophenotypic profiles and molecular characteristics into BM and PB morphology, improves the diagnostic validity. SMZL is an indolent lymphoma, although there is a small subset of patients with an aggressive clinical course[20–22]. Studies on this entity have been aggravated by the fact that the disease is very rare[23].

The purpose of this pilot study is to show PH features, as well as clinical data and follow-up in splenectomy with chemotherapy vs surgery alone treated SMZL ± VL patients.

The study group included 30 patients with SMZL ± VL. Splenectomy plus chemotherapy was applied to 20 patients, while splenectomy as a single treatment-option was performed for ten patients. The follow-up time was 12 years (1994-2006). Diagnosis was established and confirmed after initial splenectomy with consecutive PH and immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis, only upon consensus of two independent hemato-pathologists. Criterion of SMZL + VL was more than 20% of such lymphocytes in the peripheral blood[1]. Clinical stage (CS) was determined according to the Ann Arbor staging classification[24]. The following clinical characteristics were analyzed: sex, age, constitutional “B” symptoms, CS, and time from the onset of first symptoms to the beginning of treatment. Thereafter, complete blood count and standard biochemical analyses were done as follows: serum iron (sFe), ferritin, lymphoma activity parameters: lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and beta-2-microglobulin (β-2M), serum paraprotein presence (M-component), virological analysis (hepatitis B, C and HIV markers). The size of the spleen was determined by ultrasound (US) or computerized tomography (CT). Its weight in grams was also measured after spleen removal.

Diagnosis was based on analysis of tissue samples (spleen, lymph node, and BM) according to criteria of WHO classification system. All tissue samples were fixed in B5, processed by standard methods, embedded in paraffin, cut by a microtome (4 μm sections) and stained by classical staining methods: hematoxylin eosin (HE), Giemsa and reticulin (Gordon-Sweet).

Immunostaining was performed using a labeled streptavidin-biotin procedure with monoclonal antibodies (DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark). The relevant antibodies used in routine diagnosis were: LCA, EMA, IgD, IgM, CD20, CD79-α, CD5, CD23, CD43, CD10, bcl-2, CD3, Cyclin D-1, and Ki-67.

The strength of CD20 antigen (Ag) expression was graduated semi-quantitatively as strong (+++), moderate (++), or weak (+) according to cell positivity, almost in all cells, more than 50%, and in less than 50% of cells, respectively. For other antigens, expression was graded as, positive (+) or negative (-), whilst Ki-67 expression was evaluated numerically as a percentage of positive cells. Splenic marginal zone areas were selected, focusing in all cases on the areas with the highest growth fraction. Preparations of spleen, lymph nodes and BM were analyzed by standard light microscopy.

The initial treatment in all (30) patients was splenectomy. The CHOP (cyclophosphamide, hydrodoxorubicine, vincristin, and prednisolone) protocol was applied in nine (45.0%) cases. Fludarabine containing regimens (FMD - fludarabine, mitoxantrone, dexasone; and FMC - fludarabine, mitoxantrone, cyclophosphamide) were used in 11 (55.0%) cases. The decision to give additional chemotherapy was made according to the presence of constitutional “B” symptoms at presentation and lymphadenopathy. Two types of applied treatment (splenectomy alone or splenectomy with chemotherapy) in a 3-year follow-up period were analyzed for every patient.

Among descriptive analysis, the arithmetical mean and standard deviation were used for parametric data and the median was used for description of non-parametric data. For the parametric analytical model, we applied Student’s t-test. For non-parametric analytical models, we used Pearson’s χ2 tests, Fisher’s exact test, Kolmogorov-Smirnov’s test, and Kaplan-Maier’s method for analysis of OS. For significance, α errors of 0.05 were chosen in all methods. SPSS version 6.0 for Windows was used to create a database. Statistical analyses were completed within the statistics package of the Institute of Medical Statistics and Information Technology, School of Medicine, Belgrade.

There were 11/30 (36.7%) males and 19/30 females (63.3%). The mean age was 58 years (range, 33-76). Performance status according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale was 0 = 18%, 1 = 56%, and 2 = 26%. SMZL was diagnosed in 18 patients (60.0%), and SMZL + VL was found in 12 (40.0%) cases. The patients’ general clinical features and hematological characteristics included in this study are summarized in Table 1.

| Clinical stage | n(%) | |

| I E A+B | 4 (13.3) | |

| II A+B | 0 | |

| III A+B | 0 | |

| IV A+B | 24 (80.0) | |

| V A+B | 2 (6.7) | |

| Spleen-specific data | Range | Mean |

| US length of spleen (cm) | 6-32 | 22.72 |

| US width of spleen (cm) | 7-18 | 10.00 |

| CT length of spleen (cm) | 7-27 | 22.00 |

| CT width of spleen (cm) | 6-17 | 10.00 |

| Spleen weight after surgery (g) | 50-8000 | 2236 |

| Spleen infiltration: nodular vs diffuse | 18 (60.0) vs 12 (40.0) | |

| Hb (g/L) | 79-131 | 110 |

| Anemia (Hb < 100 g/L) | 27 (90.0) | |

| Leukocytosis (WBC > 10 × 109/L) | 10 (33.3) | |

| Leukocytopenia (WBC < 4 × 109/L) | 9 (30.0) | |

| Neutrocytopenia (Ne < 1.5 × 109/L) | 16 (53.3) | |

| Lymphocytosis (Ly > 5 × 109/L) | 17 (56.7) | |

| Thrombocytopenia (Plt < 150 × 109/L) | 18 (60.0) | |

| Thrombocytosis (Plt > 400 × 109/L) | 5 (16.7) | |

| Serum paraprotein (determined) | 23 (76.7) | |

| IgG lambda (found) | 1 (3.3) | |

| LDH elevated (> 320 U/L) | 8 (26.7) | |

| β-2M elevated (> 1.8 μg/L) | 25 (83.3) | |

Furthermore, HIV 1 and 2 antibodies were all negative (100%). Hepatitis B antibodies were also negative in all patients. Hepatitis C antibodies were positive in only one case (3.3%).

The mean sFe level was 7.24 μg/L (range, 2.20-16.2). Decreased values below absolute in relation to gender were recorded in 19 (63.3%) patients, and normal were reported in 11 (36.7%) subjects. Relative iron deficiency might be explained in two ways. Firstly, iron resorption was reduced due to loss of appetite with an increase of passive intestinal hyperemia on account of splenomegaly. Secondly, more intensive loss of the same oligo-element was stimulated by hemorrhage, (most often occult). Ferritin levels were within normal limits in relation to gender in all subjects.

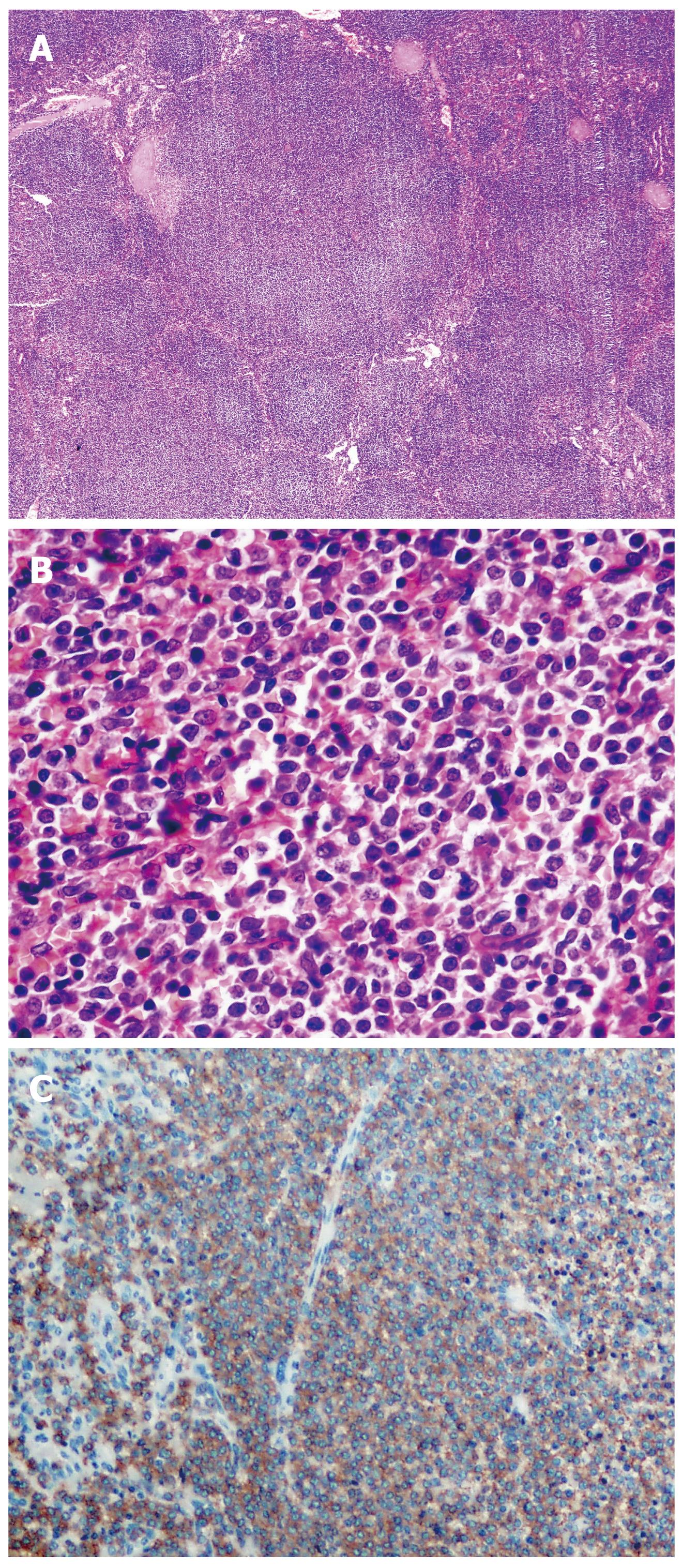

A total of 30 (100%) patients with typical histological and immunohistochemical splenic marginal zone lymphoma pattern were examined (Figure 1).

Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that none of the positive expressing antigens had a significant influence on disease outcome, as assessed using a χ2 test with the following confirmed results: CD79-alfa (χ2 = 5.074, P > 0.05), CD20 (χ2 = 4.046, P > 0.05), CD43 (χ2 = 0.910, P > 0.05). IgD (χ2 = 2.503, P > 0.05), IgM (χ2 = 1.147, P > 0.05), bcl-2 (χ2 = 3.667, P > 0.05), and Ki-67 (χ2 = 2.503, P > 0.05). Moreover, Ki-67 positivity varied from 5%-35%, with following distributions: 5%-15%, 15%-25%, and 25%-35% in nine (30.0%), 14 (46.7%) and seven patients (23.3%), respectively.

Using the long rank test in the Kaplan Mayer method of survival showed that among all antigens, only CD20 antigen had some impact on OS. Namely, among three groups of patients according to CD20 positivity (strong, moderate, weak), median survival was 113 mo, 83 mo, and only 43 mo, respectively (Log rank = 5.244, P < 0.05).

In this study, all the patients were splenectomized at the beginning of treatment. Therapeutic splenectomy, i.e. as the only curative modality in 10 (33.3%) patients was performed. Splenectomy with chemotherapy (different protocols) was done in the remaining 20 (66.7%) patients. After a mean three-year follow-up, the outcome was as follows: 20 (66.7%) patients had complete remission (CR), seven (23.3%) had partial remission (PR), and three (10.0%) died due to disease progression.

Out of 10 patients having undergone splenectomy only, eight (80.0%) had CR and two (20.0%) had significant PR (76 mo). In addition, all CR were stable after five years (60 mo). No patient with spleen rupture, a rare but possible complication, was reported.

Out of those receiving chemotherapy after splenectomy (20 patients), CR was achieved in 11 (55.0%) patients. The CHOP protocol was used in nine (45.0%) cases, and FMD or FMC were used in 11 (55.0%) cases. Ultimately, the mode of treatment was not a factor interfering with OS of our patients. Median survival of patients with splenectomy only was 93.0 mo and in patients with splenectomy and chemotherapy it was 107.5 mo (Log rank = 0.056, P > 0.05).

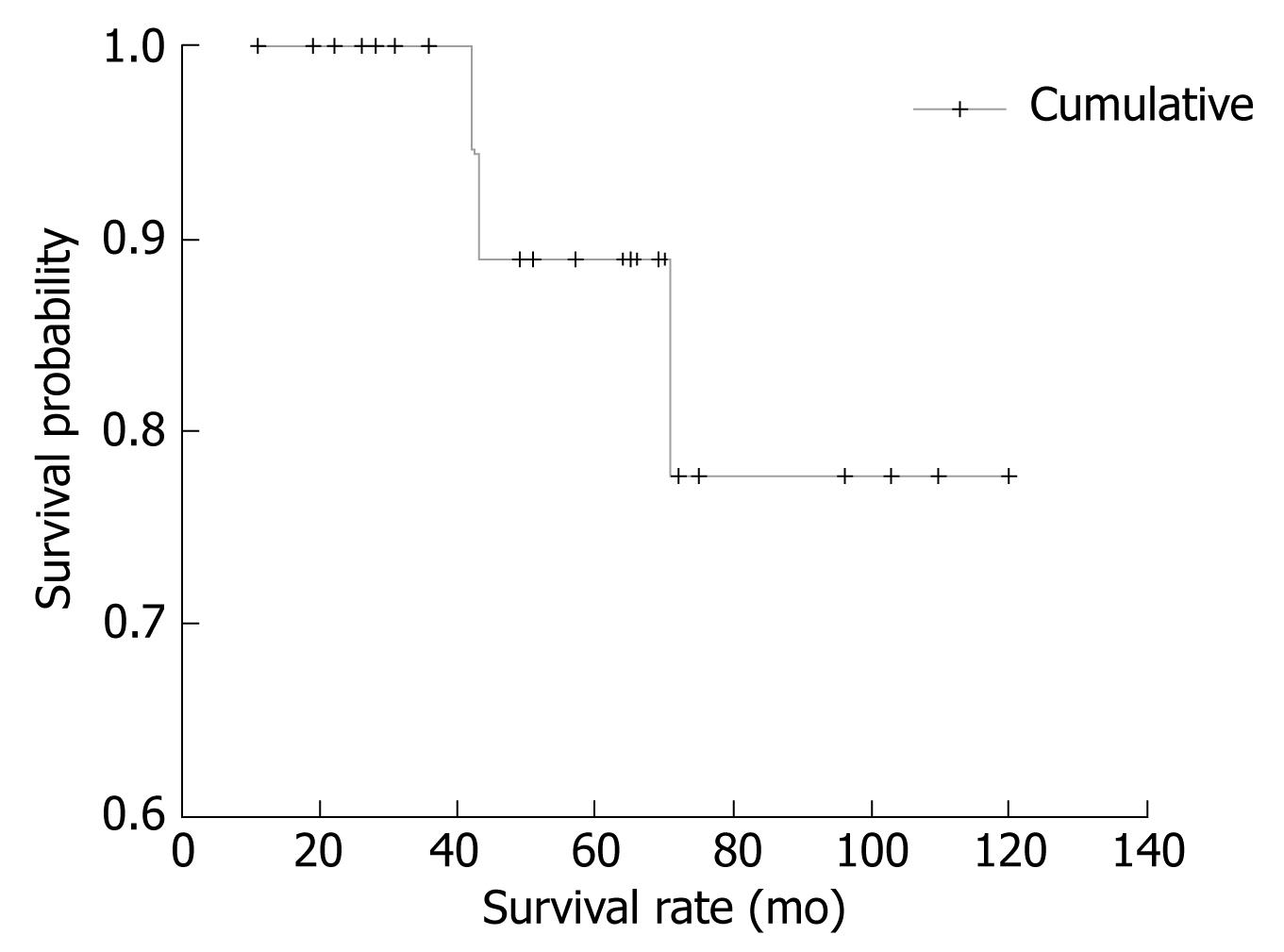

The cumulative survival of patients included in this study is presented in Figure 2.

As shown, after 120 mo of follow-up, the incidence of survival was constant (about 77%). Time from onset of first symptoms to the beginning of treatment (mean 9.4 mo, range 1-84) was influenced by spleen dimension, as measured by CT and US, and was significantly shorter in patients with higher spleen dimensions (t = 2.558, P = 0.018). The highest mean values of segmented neutrophil percentage were found in subjects who reached CR, and conversely, the lymphocyte percentage mean values were lowest in those who achieved CR (P = 0.026).

Spleen dimensions measured by CT also correlated with clinical stage (P = 0.034).

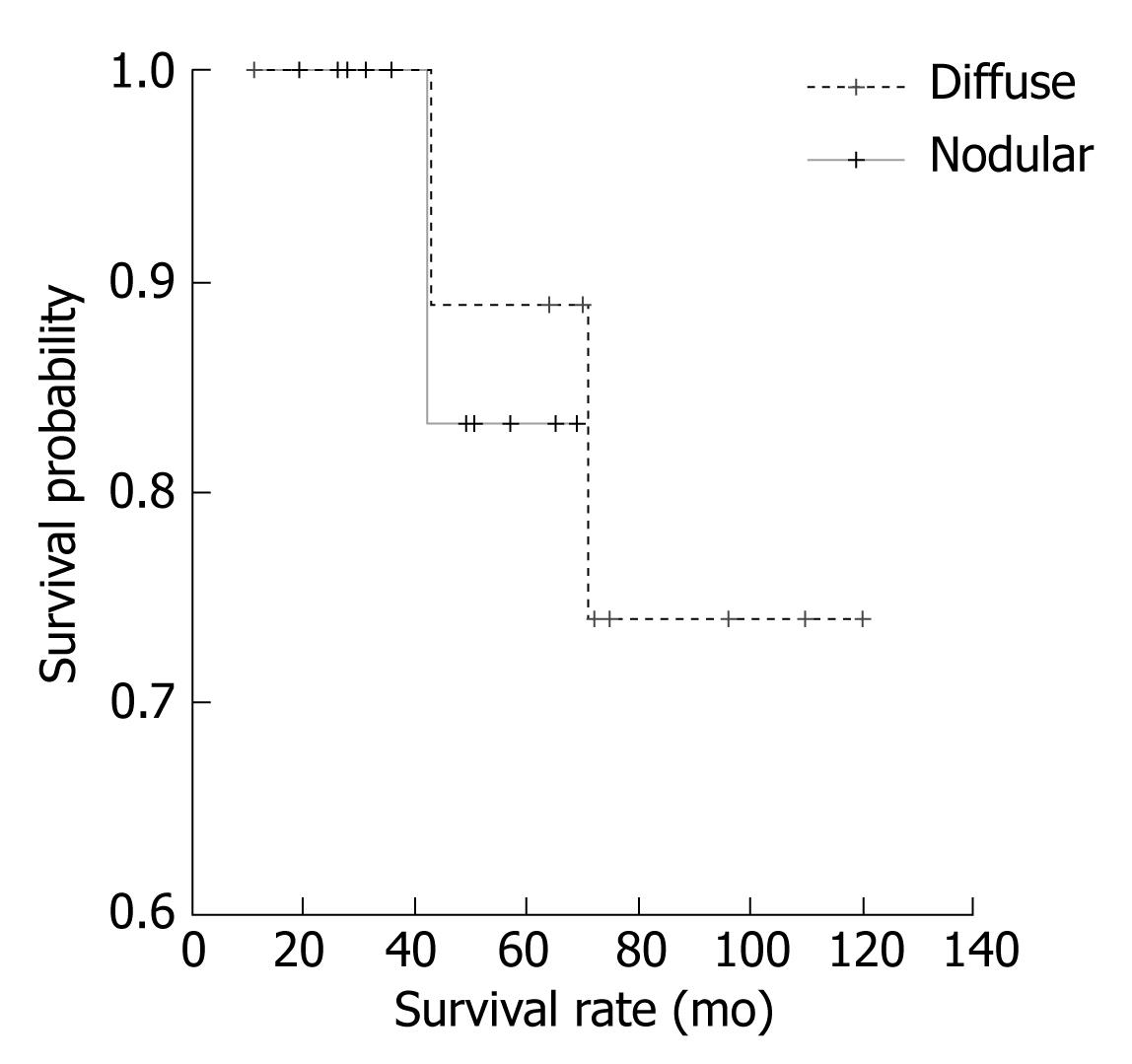

The analysis of factors interfering with survival, as measured by the Kaplan-Meier method, revealed that gender was not a factor affecting the length of survival (Log rank = 0.643, P > 0.05). Further analysis of such factors showed that the presence of “B” symptoms also had no effect on survival (Log rank = 0.141, P > 0.05). Moreover, CS was not a factor affecting patient survival. (Log rank = 0.560, P > 0.05). Similarly, the type of spleen infiltration (nodular vs diffuse) was not a factor affecting the survival of patients (Log rank = 0.021, P > 0.05), as shown in Figure 3.

Finally, the analysis of lethal outcome predictors by the Cox regression model included the role of factors that could have any effect on such an outcome (Table 2). As illustrated, none of the studied factors appeared to be significant for predicting treatment outcome in our group of patients.

| Variables | Score | df | P |

| Gender | 0.244 | 1 | 0.621 |

| Age | 0.657 | 1 | 0.418 |

| Time from the onset of B symptoms to treatment | 13.906 | 10 | 0.177 |

| CS | 0.557 | 2 | 0.757 |

| Spleen infiltration (nodular vs diffuse) | 0.009 | 1 | 0.923 |

| Mode of treatment | 0.089 | 1 | 0.900 |

Splenic marginal zone lymphoma is a relatively rare entity with a slight male predominance. In our group of patients there was higher incidence of female - 19 (63.3%), in relation to male - 11 (36.7%), as compared to other studies[2526]. The mean patients’ age was 58.2 years, which agreed with the fact that splenic lymphoma is a disease of older age[17].

A majority of the SMZL cases studied carried a non-mutated bcl-6 gene[14]. The frequency of these mutations in normal spleen confirms previous findings on the hyper-mutation IgVH process in normal B-cell populations[2728]. This data supported the existence of molecular heterogeneity in this entity. It also favored the hypothesis that, in spite of initial morphological observations, a significant proportion of SMZL cases could derive from an non-mutated naive precursor, which is different from those of the marginal zone, and possibly located in the mantle zone of splenic lymphoid follicles. Thus, the marginal zone differentiation of these tumors could be related more to the splenic microenvironment than to the histogenetic characteristics of the tumor[20].

Considering PH findings, in our group there were 18 patients (60.0%) with SMZL, and 12 (40.0%) with SMZL + VL. The largest number of patients had advanced disease in clinical stage IV + V (86.7%). The shortest time of the onset of first symptoms to the beginning of treatment was one month, and the longest was 84 mo. The average was 9.4 mo it was correlated with spleen dimension, as measured by CT and US. It was significantly shorter in patients with higher spleen dimensions. SMZL is a slow-course disease and is detected in progressive phase in the highest percentage[729]. In accordance with this, Thieblemont found BM infiltration in 95% of patients[1]. Almost all (97%) patients had clinical stage III and IV, as reported in the large cohort of patients published by Arcaini[25], with a similar proportion of about 90% of BM infiltration in a series of 129 patients[30]. It was apparent that the majority of patients in our study were in clinical stage IV.

Splenomegaly lasted approximately 9.4 mo before diagnosis (interval of 1-36 mo), referring to a study in 1999[26], which is similar with our results. Another study on 18 patients established an average pre-treatment presence of symptoms to be four months (two-six month interval)[31]. Similarly, a series of 17 patients reported pre-treatment duration of symptoms varying from several days to four months with a mean time of 2.1 mo[9].

The finding that spleen dimension correlated with clinical stage, as well as with the time from onset of first symptoms to the beginning of treatment, is rational since the dominant tumor mass is in the spleen. The maximal weight of the spleen measured intraoperatively was 8000 g and minimal weight was 450 g (mean = 2235.7 g). Such a finding suggested that there was at least one a case with a huge splenomegaly, rarely seen in foreign literature[2326]. The pattern of spleen infiltration (nodular vs diffuse) was not significant for OS in our group of patients. According to the literature, 85% of patients with relapsed or progressive disease have nodal involvement, with a relatively low frequency of nodal involvement at initial diagnosis[23]. This emphasizes the care necessary in sorting nodal involvement of SMZL from primary nodal MZL, and the necessity of differential diagnosis with additional molecular markers.

We found that 27 (90.0%) patients manifested a lower or higher degree of anemia. Anemia is strongly characteristic of spleen lymphoma. It occurs due to hypersplenism rather than BM infiltration[17]. In a series of 81 patients reported by Thieblemont, 44 with spleen lymphoma had anemia and of these, 13 had Coombs-positive hemolytic anemia[1]. Similar results, with about half of the patients being anemic, were published for a large group of 309 patients[25].

Despite the presence of anemia (Hb ≤ 110 g/L) in about 30% of patients with SMZL ± VL with mean value of hemoglobin 118 g/L[30], the percentage of anemic cases in our patients was significant higher, due to the predominance of advanced clinical stage. Leukocytosis and leukocytopenia were found in about a third of the patients, whilst half of the patients had neutrocytopenia and lymphocytosis. Such percentage of cells, rather than platelet count, in our patients was of no prognostic value regarding the survival period. A higher rate of achieving CR was found in patients with higher initial segmented neutrophil count and with a lower level of lymphocytes at presentation.

The distribution of serum paraprotein has varied from 8%[25], which was comparable to our results, to as much as 46%[1]. In a third large series of 129 patients with spleen lymphoma, paraprotein was present in 22% of patients, with the highest concentration of 25 g/L, but without any prognostic value[30]. Contrastingly, Arcaini reported that the presence of paraprotein had prognostic value in terms of shorter time to disease progression[32].

The established positivity of hepatitis C virus antibodies varied from 1%[1], which was similar to our results, to 19%, while hepatitis B virus antibodies were detected in 5% of cases[25].

Serum LDH is an important activity parameter of aggressive disease, while in low-aggressive ones, its increase can designate the transformation of disease to more severe form[18]. In our study group, this parameter was within referential limits in 72% of patients, which suggested low-grade disease status. On the other hand, Chacon reported about 60% patients with significantly elevated LDH[23].

In our patients, β-2M was predominantly elevated (83.3%), ranging from 2.38 to 7.4 μg/L. The results are in accordance with the established fact that this parameter is increased in SMZL as a negative prognostic marker[3334].

Regarding the type and outcome of treatment, our results indicated that the use of adjuvant chemotherapy following the splenectomy had no influence on OS rate, as reported in published series so far[1723]. This finding is in accordance with the fact that the use of alkylating drug therapy yields a rate of response of about 44%, but complete remissions are rare, probably due to the existing BM infiltration[17]. Until now, the treatment of SMZL has been controversial. In all large series, a significant group of patients received no therapy. These patients do not seem to have worst outcome than those initially treated. For these reasons, and assuming that SMZL is an indolent disease, some authors recommend a “watch and wait” approach[23]. Although, in general SMZL behaves as an indolent disease, there is a significant group of patients who died from the disease in a relatively short time period. The role of chemotherapy is still a matter of debate. One of the striking findings is the relatively low percentage of patients who attain CR after chemotherapy, because of the presence of BM involvement after chemotherapy[23]. The literature presents diverse chemotherapy regimens for SMZL. Generally, splenectomy leads to somatic compensation of patients, rendering it impossible for local relapse in the spleen, prevents continuous dissemination from the primary tumor site, and mostly corrects cytopenias, creating better conditions for chemotherapy[35].

SMZL is a relatively indolent disease, but in some cases it displays more aggressive behavior, which should stimulate the search for predictive biologic factors and alternative therapies. Early splenectomy combined with chemotherapy in properly stratified patients at presentation has been shown to be beneficial because of improvement in remission rate/duration and superior OS. However, there was no statistical significance, probably due to the limited number of patients. Thus, the evaluation of these therapeutic approaches requires larger, randomized, and controlled clinical studies.

Splenic marginal-zone lymphoma (SMZL) is a relative uncommon low-grade lymphoma and primary disease of the spleen, with bone marrow and peripheral blood involvement. The existence of molecular heterogeneity in this entity gave additional results in favor of the hypothesis that, in spite of initial morphological observations, most SMZL cases could derive from a non-mutated naive precursor, different from those of the marginal zone, and possibly located in the mantle zone of splenic lymphoid follicles. Thus the marginal zone differentiation could be related more to the splenic microenvironment than it is to the histogenetic characteristics of the tumor. Until now, standard prognostic factors could not differentiate patients into groups with poor or favorable clinical outcome.

Despite the evaluation of different prognostic factors, the treatment of SMZL is still controversial. However, several immune-mediated events, such as hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia, as well as the presence of the serum monoclonal component, could be predictive factors for survival-rate. Splenectomy is considered the first-line treatment. Even when this therapy results in partial remission, the response to the surgery is usually sufficient to correct cytopenia and also to improve the patient’s quality of life, as well as overall survival-rate.

SMZL is an indolent lymphoma, although there is a small subset of patients with an aggressive clinical course. Despite this fact, there have been significant groups of patients who have received no therapy, with only a “watch and wait” approach being adopted to their indolent clinical course. Early splenectomy combined with consecutive chemotherapy leads to somatic compensation of patients, renders it impossible for local relapse in the spleen, prevents continuous dissemination from the primary tumor site, commonly corrects cytopenias, and improves the survival-rate.

This data shows that early splenectomy combined with chemotherapy at presentation leads to some improvements in duration of overall survival, although with no statistical significance, probably due to the limited number of patients. Therefore, future approaches will need well controlled and larger clinical studies.

In this manuscript, the authors delivered some interesting data on clinical-pathological features and clinical outcomes of 30 SMZL patients. They confirm that early splenectomy, at the beginning of treatment, combined with chemotherapy is helpful to prevent disease recurrence. The data presented might be beneficial for clinical treatment of patients with SMZL.

| 1. | Thieblemont C, Felman P, Callet-Bauchu E, Traverse-Glehen A, Salles G, Berger F, Coiffier B. Splenic marginal-zone lymphoma: a distinct clinical and pathological entity. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:95-103. |

| 2. | Kahl B, Yang D. Marginal zone lymphomas: management of nodal, splenic, and MALT NHL. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2008;4:359-364. |

| 3. | Zucca E, Bertoni F, Stathis A, Cavalli F. Marginal zone lymphomas. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008;22:883-901, viii. |

| 4. | Kost CB, Holden JT, Mann KP. Marginal zone B-cell lymphoma: a retrospective immunophenotypic analysis. Cytometry B Clin Cytom. 2008;74:282-286. |

| 5. | Dogan A. Modern histological classification of low grade B-cell lymphomas. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2005;18:11-26. |

| 6. | Maes B, De Wolf-Peeters C. Marginal zone cell lymphoma--an update on recent advances. Histopathology. 2002;40:117-126. |

| 8. | Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Diebold J, Flandrin G, Muller-Hermelink HK, Vardiman J, Lister TA, Bloomfield CD. The World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Report of the Clinical Advisory Committee meeting, Airlie House, Virginia, November, 1997. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:1419-1432. |

| 9. | Dachman AH, Buck JL, Krishnan J, Aguilera NS, Buetow PC. Primary non-Hodgkin's splenic lymphoma. Clin Radiol. 1998;53:137-142. |

| 11. | Kumagawa M, Suzumiya J, Ohshima K, Kanda M, Tamura K, Kikuchi M. Splenic lymphoproliferative disorders in human T lymphotropic virus type-I endemic area of japan: clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and genetic analysis of 27 cases. Leuk Lymphoma. 2001;41:593-605. |

| 12. | Landgren O, Tilly H. Epidemiology, pathology and treatment of non-follicular indolent lymphomas. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49 Suppl 1:35-42. |

| 13. | Arcaini L, Sacchi P, Jemos V, Lucioni M, Rumi E, Dionigi P, Paulli M. Splenic marginal zone B-cell lymphoma in a HIV-positive patient: a case report. Ann Hematol. 2009;88:379-381. |

| 14. | Ruiz-Ballesteros E, Mollejo M, Rodriguez A, Camacho FI, Algara P, Martinez N, Pollán M, Sanchez-Aguilera A, Menarguez J, Campo E. Splenic marginal zone lymphoma: proposal of new diagnostic and prognostic markers identified after tissue and cDNA microarray analysis. Blood. 2005;106:1831-1838. |

| 15. | Aggarwal M, Villuendas R, Gomez G, Rodriguez-Pinilla SM, Sanchez-Beato M, Alvarez D, Martinez N, Rodriguez A, Castillo ME, Camacho FI. TCL1A expression delineates biological and clinical variability in B-cell lymphoma. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:206-215. |

| 16. | Hömig-Hölzel C, Hojer C, Rastelli J, Casola S, Strobl LJ, Müller W, Quintanilla-Martinez L, Gewies A, Ruland J, Rajewsky K. Constitutive CD40 signaling in B cells selectively activates the noncanonical NF-kappaB pathway and promotes lymphomagenesis. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1317-1329. |

| 17. | Boveri E, Arcaini L, Merli M, Passamonti F, Rizzi S, Vanelli L, Rumi E, Rattotti S, Lucioni M, Picone C. Bone marrow histology in marginal zone B-cell lymphomas: correlation with clinical parameters and flow cytometry in 120 patients. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:129-136. |

| 18. | Dungarwalla M, Appiah-Cubi S, Kulkarni S, Saso R, Wotherspoon A, Osuji N, Swansbury J, Cunningham DC, Catovsky D, Dearden CE. High-grade transformation in splenic marginal zone lymphoma with circulating villous lymphocytes: the site of transformation influences response to therapy and prognosis. Br J Haematol. 2008;143:71-74. |

| 19. | Inamdar KV, Medeiros LJ, Jorgensen JL, Amin HM, Schlette EJ. Bone marrow involvement by marginal zone B-cell lymphomas of different types. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:714-722. |

| 20. | Mollejo M, Camacho FI, Algara P, Ruiz-Ballesteros E, García JF, Piris MA. Nodal and splenic marginal zone B cell lymphomas. Hematol Oncol. 2005;23:108-118. |

| 21. | Ott MM, Müller-Hermelink HK. [Splenic marginal zone B cell lymphomas]. Pathologe. 2008;29:143-147. |

| 22. | Marx A, Müller-Hermelink HK, Hartmann M, Geissinger E, Zettl A, Adam P, Rüdiger T. [Lymphomas of the spleen]. Pathologe. 2008;29:136-142. |

| 23. | Chacón JI, Mollejo M, Muñoz E, Algara P, Mateo M, Lopez L, Andrade J, Carbonero IG, Martínez B, Piris MA. Splenic marginal zone lymphoma: clinical characteristics and prognostic factors in a series of 60 patients. Blood. 2002;100:1648-1654. |

| 24. | Zucca E, Bertoni F, Cavalli F. Marginal zone B-cell lymphomas. The lymphomas. 2nd ed. Saunders Elsevier Company: Philadelphia 2006; 381-396. |

| 25. | Arcaini L, Lazzarino M, Colombo N, Burcheri S, Boveri E, Paulli M, Morra E, Gambacorta M, Cortelazzo S, Tucci A. Splenic marginal zone lymphoma: a prognostic model for clinical use. Blood. 2006;107:4643-4649. |

| 26. | Pittaluga S, Verhoef G, Criel A, Wlodarska I, Dierlamm J, Mecucci C, Van den Berghe H, De Wolf-Peeters C. "Small" B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphomas with splenomegaly at presentation are either mantle cell lymphoma or marginal zone cell lymphoma. A study based on histology, cytology, immunohistochemistry, and cytogenetic analysis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:211-223. |

| 27. | Parrens M, Gachard N, Petit B, Marfak A, Troadec E, Bouabdhalla K, Milpied N, Merlio JP, de Mascarel A, Laurent C. Splenic marginal zone lymphomas and lymphoplasmacytic lymphomas originate from B-cell compartments with two different antigen-exposure histories. Leukemia. 2008;22:1621-1624. |

| 28. | Raya JM, Ruano JA, Bosch JM, Golvano E, Molero T, Lemes A, Cuesta J, Brito ML, Hernández-Nieto L. Splenic marginal zone lymphoma--a clinicopathological study in a series of 16 patients. Hematology. 2008;13:276-281. |

| 29. | Chang ST, Hsieh YC, Lu YH, Tzeng CC, Lin CN, Chuang SS. Floral leukemic cells transformed from marginal zone lymphoma. Pathol Res Pract. 2008;204:23-26. |

| 30. | Parry-Jones N, Matutes E, Gruszka-Westwood AM, Swansbury GJ, Wotherspoon AC, Catovsky D. Prognostic features of splenic lymphoma with villous lymphocytes: a report on 129 patients. Br J Haematol. 2003;120:759-764. |

| 31. | Carr JA, Shurafa M, Velanovich V. Surgical indications in idiopathic splenomegaly. Arch Surg. 2002;137:64-68. |

| 32. | Arcaini L, Paulli M, Boveri E, Magrini U, Lazzarino M. Marginal zone-related neoplasms of splenic and nodal origin. Haematologica. 2003;88:80-93. |

| 33. | Gribben JH, La Casce SA. Clinical manifestations, staging, and treatment of Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma. Hematology, Basic Principles and Practice. 4th ed. Churchill Livingstone: Elsevier, Pennsylvania 2005; 1385-1409. |

| 34. | Iannitto E, Ambrosetti A, Ammatuna E, Colosio M, Florena AM, Tripodo C, Minardi V, Calvaruso G, Mitra ME, Pizzolo G. Splenic marginal zone lymphoma with or without villous lymphocytes. Hematologic findings and outcomes in a series of 57 patients. Cancer. 2004;101:2050-2057. |

| 35. | Musteata VG, Corcimaru IT, Iacovleva IA, Musteata LZ, Suharschii IS, Antoci LT. Treatment options for primary splenic low-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphomas. Clin Lab Haematol. 2004;26:397-401. |