INTRODUCTION

Gastrointestinal and mesenteric lymphangioma or lymphangiomatosis are extremely rare in adults[1–3]. A lymphangioma usually appears as a partially septated, cystic mass on imaging studies including ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). CT is a basic imaging modality for detecting and evaluating various malignancies. Occasionally, lymphangioma may appear as a solid or infiltrative soft tissue mass on CT because of its microcystic nature or if there is intracystic debris or hemorrhage. The non-cystic appearance of mesenteric lymphangioma may be confused on CT with metastasis or a malignant tumor, especially in patients with malignancy. 18F-FDG positron emission tomography (PET)/CT may have an important role for staging malignancy because hypermetabolic tumor cells actively uptake 18F-FDG[4]. This report describes the CT and 18F-FDG PET/CT appearance of a mesenteric and jejunal lymphangiomatosis mimicking metastasis in an adult patient with rectal cancer.

CASE REPORT

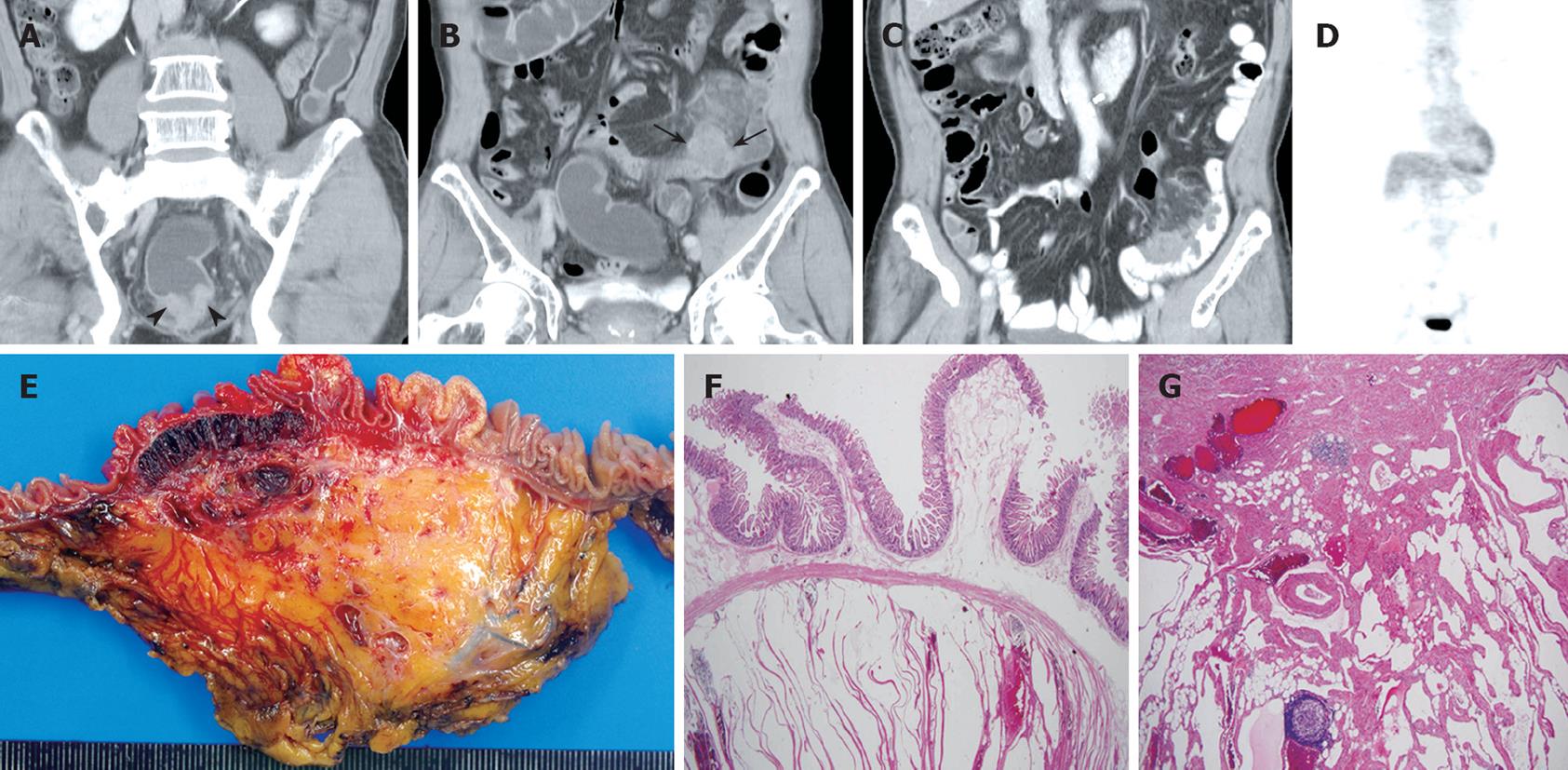

A 71-year-old man was referred for evaluation of a rectal cancer detected on colonoscopy and CT during an evaluation of hematochezia. He had a 5-year history of taking medication for underlying angina. Rectal examination showed a hard mass in the rectum. The standard laboratory tests were normal. Rectal cancer was seen as segmental and irregular wall thickening in the distal rectum with several enlarged perirectal lymph nodes on contrast-enhanced CT (Figure 1A). The soft-tissue density of the nodular mass and hazy attenuations in the jejunal mesentery (Figure 1B) were overlooked initially on either CT scans or on surgery. The patient underwent laparoscopic abdominal transanal resection and ileostomy. Adjuvant chemotherapy and ileostomy closure were performed during the year following surgery. Follow-up, contrast-enhanced CT revealed nodular jejunal and adjacent mesenteric masses in contrast to the barium-filled jejunum; the masses measured approximately 8 cm × 6 cm in width (Figure 1C). Under the suspicion of mesenteric and jejunal wall metastasis from the rectal cancer, 18F-FDG PET/CT was performed, but no remarkable FDG uptake was seen (Figure 1D). Pathological examination of a resected segment of the jejunum revealed a macroscopic, dark red, multiloculated cystic lesion measuring 8.0 cm × 5.0 cm from the mucosa to the subserosa (Figure 1E). Microscopically, it showed numerous multiloculated, cystically dilated spaces lined by attenuated endothelium and involved mucosa to subserosa. In the focal area, ectatic spaces appeared to dissect through the muscularis propria of the small intestine. Proteinaceous, fluid-containing lymphocytes seen in the cystic spaces revealed that the channel originated in the lymphatic system. The stroma was composed of a delicate meshwork of collagen punctated by lymphoid aggregates (Figure 1F). Immunohistochemical staining for CD34 showed positivity in the endothelial cells of the tumor (Figure 1G). The diagnosis of cavernous lymphangioma involving the jejunum and mesentery was established. The patient had an uneventful postoperative course and was discharged one week after surgery.

Figure 1 A 71-year-old man with rectal cancer and mesenteric lymphangioma.

A, B: Contrast-enhanced, coronal CT images show irregular and concentric rectal wall thickening (arrow heads), a nodular soft-tissue-density mass, and hazy strands in the jejunal mesentery (arrows); C: Follow-up, contrast-enhanced, coronal CT obtained one year after laparoscopic rectal cancer resection, reveals clear demarcation of the jejunal nodular lesions and infiltrative soft tissue masses in the adjacent mesentery. No remarkable jejunal obstruction was found; D: 18F-FDG PET shows no 18F-FDG uptake in the jejunum or mesenteric lesions; E: The cut section of the jejunum reveals a dark-red, multiloculated, cystic lesion measuring 8.0 cm × 5.0 cm in the mucosa to the subserosa; F, G: Histopathologic view of the tumor shows numerous, multiloculated, cystically dilated lymphatic spaces lined by attenuated endothelium in the entire jejunal wall (HE stain, × 40) and adjacent mesentery (HE, × 20).

DISCUSSION

Lymphangioma or lymphangiomatosis affect the skin, the covering of various organs and areas except of the brain. About 90% are diagnosed within the first two years of their existence[12]. In adults, gastrointestinal tract involvement of mesenteric lymphangioma is very rare, the distal ileal mesentery is most frequently involved[3]. The etiology of lymphangiomas is still unclear. They are considered to be a congenital dysplasia of lymphatic tissue and abnormal development of the lymphatic vessels during fetal life[56]. The macroscopic appearance of lymphangioma is a cystic mass with partial septations and its histological characteristics are endothelial-lined, dilated, communicating lymphatic channels containing a variable amount of connective tissue and smooth muscle fiber[57]. Lymphangiomas are generally classified as simple capillary, cavernous, and cystic according to the size of lymphatic space and the nature of the lymphatic wall[89]. Cavernous lymphangioma is composed of dilated lymphatic vessels and lymphoid stroma and is connected with the adjacent normal lymphatics. Alternatively, cystic lymphangioma is composed of various-sized lymphatic spaces and has no connection with the adjacent normal lymphatics. However, as cystic lymphangiomas may have a cavernous area, clear differentiation between cystic and cavernous lymphangioma is not always possible[910].

Most intra-abdominal lymphangiomas are of cystic form and generally appear as a thin-walled, mutiseptated, cystic mass with or without intracystic debris. Although these lymphangioma characteristics may appear in typical, mutiseptated, cystic masses on images including ultrasound and CT, some lymphangiomas may appear to be solid masses because they contain intracystic debris or hemorrhage or due to the microcystic nature of cavernous lymphangiomas. MRI is advantageous for detecting fluid-filled cystic lesions as it may reveal the cystic nature of cavernous lymphangiomas that appear as solid masses on CT[11]. In our patient with rectal cancer, multiple nodular mesenteric masses infiltrating into the jejunum and adjacent mesentery were found. Because we did not suspect the microcystic nature of cavernous lymphangiomas, MRI was not performed to differentiate a microcystic tumor mimicking a solid mass.

As 18F-FDG is an analogue of glucose, its uptake within viable tumor cells is in proportion to the rate of glycolysis. Therefore, as 18F-FDG PET/CT can detect hypermetabolic tumor cells, it can be widely used for the detection, staging, and management of various malignant tumors[4]. In our patient, as 18F-FDG PET/CT revealed no remarkable 18F-FDG uptake within the solid, mass-like lesions in the jejunal and adjacent mesentery, we were able to exclude the possibility of metastasis from the underlying rectal cancer.

The clinical symptoms of gastrointestinal and mesenteric lymphangiomas vary from being asymptomatic to acute abdominal symptoms such as obstruction or bleeding, according to the size and the localization of the tumor[101213]. The treatment of choice is complete surgical resection. Because lymphangioma is benign in nature, the prognosis is usually good despite the possibility of tumor recurrence. As Goh et al[14] reported a 100% recurrence rate, complete lymphangioma resection is important in order to prevent tumor recurrence.

In conclusion, rarely occurring, cavernous mesenteric lymphangioma in adults occasionally appears on CT as a solid mass and it may be confused with metastasis in patients with malignancies. Therefore, 18F-FDG PET/CT may be helpful in excluding the presence of metastasis.