Published online Aug 14, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3823

Revised: June 30, 2009

Accepted: July 7, 2009

Published online: August 14, 2009

A 48-year-old Indian male with alcoholic liver cirrhosis was admitted after being found unresponsive. He was hypotensive and had hematochezia. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) showed small esophageal varices and a clean-based duodenal ulcer. He continued to have hematochezia and anemia despite blood transfusions. Colonoscopy was normal. Repeat EGD did not reveal any source of recent bleed. Twelve days after admission, his hematochezia ceased. He refused further investigation and was discharged two days later. He presented one week after discharge with hematochezia. EGD showed non-bleeding Grade 1 esophageal varices and a clean-based duodenal ulcer. Colonoscopy was normal. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed liver cirrhosis with mild ascites, paraumbilical varices, and splenomegaly. He had multiple episodes of hematochezia, requiring repeated blood transfusions. Capsule endoscopy identified the bleeding site in the jejunum. Concurrently, CT angiography showed paraumbilical varices inseparable from a loop of small bowel, which had herniated through an umbilical hernia. The lumen of this loop of small bowel opacified in the delayed phase, which suggested variceal bleeding into the small bowel. Portal vein thrombosis was present. As he had severe coagulopathy and extensive paraumbilical varices, surgery was of high risk. He was not suitable for transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt as he had portal vein thrombosis. Percutaneous paraumbilical embolization via caput medusa was performed on day 9 of hospitalization. Following the embolization, the hematochezia stopped. However, he defaulted subsequent follow-up.

- Citation: Lim LG, Lee YM, Tan L, Chang S, Lim SG. Percutaneous paraumbilical embolization as an unconventional and successful treatment for bleeding jejunal varices. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(30): 3823-3826

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i30/3823.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.3823

Bleeding jejunal varices can be difficult to diagnose and manage. We present a case of obscure overt gastrointestinal hemorrhage secondary to jejunal varices, detailing the extensive investigations and unconventional management.

A 48-year-old Indian male with alcoholic liver cirrhosis had been treated for ascites and encephalopathy for the prior 6 years. Variceal endoscopic ligation was performed 5 years previously for bleeding esophageal varices. In the same year, he underwent a laparotomy for repair of an incarcerated umbilical hernia. He defaulted follow-up thereafter.

Regarding the current episode, he was admitted after being found unresponsive. He was hypotensive and digital rectal examination showed hematochezia. His hemoglobin was 7.4 g/dL on admission. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) showed small esophageal varices, and a 2 cm clean-based ulcer in the duodenal bulb. He continued to have hematochezia and anemia despite blood transfusions. Colonoscopy was normal up to the cecum. Repeat EGD again did not reveal any source of recent bleed. Twelve days after admission, his hematochezia ceased, and his hemoglobin was 8.4 g/dL. He refused further investigation and was discharged two days later.

He subsequently presented one week after discharge, complaining of abdominal pain and hematochezia for two days. His blood pressure was 120/80 mmHg, and heart rate was 110 beats/min. There was no encephalopathy. He had mild ascites. Digital rectal examination showed hematochezia. Hemoglobin was 4 g/dL, platelets 63 × 109/L, prothrombin time was 22 s and albumin 15 g/L. Diagnosis was Child’s C alcoholic liver cirrhosis with possible variceal bleed. He was treated with IV esomeprazole, IV somatostatin and IV ceftriaxone and was transfused with fresh frozen plasma and packed cells. Emergency EGD showed non-bleeding Grade 1 esophageal varices and a clean-based duodenal ulcer. Colonoscopy was normal. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) showed liver cirrhosis with mild ascites, paraumbilical varices, and splenomegaly. He continued to have multiple episodes of hematochezia, requiring repeated blood transfusions.

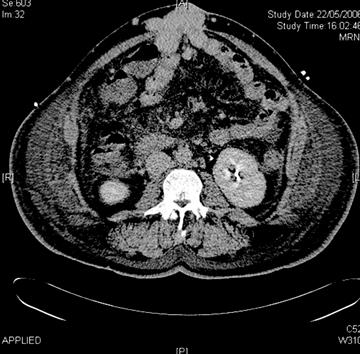

Capsule endoscopy (Figure 1) identified the bleeding site in the jejunum. Concurrently, CT angiography was also carried out, having been negative on two prior episodes of hematochezia. However, the third CT angiography (Figure 2), performed during active hematochezia, showed paraumbilical varices inseparable from a loop of small bowel which had herniated through an umbilical hernia. The lumen of this loop of small bowel opacified in the delayed phase, which suggested variceal bleeding into the small bowel. Portal vein thrombosis was present.

A decision was made for percutaneous paraumbilical embolization via caput medusae to be carried out on day 9 of hospitalization. The caput medusae near the umbilicus was punctured. When there was good return of blood, the guidewire was introduced and it was noted to pass freely into a vein. The guidewire was manipulated into the superior mesenteric and the splenic vein. Injection of contrast demonstrated the anatomy of the portovenous system clearly. The catheter tip was then positioned peripherally so that injection of contrast opacified only the veins near the ventral hernia leading into the caput. Three steel coils were placed into this vein. At the end of the study, injection of contrast under pressure did not demonstrate any retrograde flow, indicating that it was occluded (Figure 3).

Following the embolization, the hematochezia stopped. The patient remained well and somatostatin was stopped on day 12 of hospitalization. His hemoglobin rose to 9.0 g/dL and he was discharged. However, he defaulted subsequent follow-up.

Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) is categorized into obscure overt and obscure occult bleeding based on the presence or absence of clinically evident bleeding[1]. Gastroscopy and colonoscopy should be repeated in OGIB, as a bleeding source can be identified on repeat endoscopies in some patients[2]. When repeat upper and lower endoscopies are negative, the small intestine should be investigated. Diagnostic accuracy for such investigations is limited mainly by the difficulty of performing adequate studies in this uncommon condition. In a meta-analysis, capsule endoscopy was shown to be superior to push enteroscopy and small bowel barium radiography for diagnosing clinically significant small bowel pathology in patients with OGIB, with incremental yields of 30% and 36%, respectively[3]. In a prospective study comparing capsule endoscopy with double-balloon enteroscopy in 35 patients with OGIB, small-bowel abnormalities were detected using capsule endoscopy in 80% of cases, compared with 60% using double-balloon enteroscopy. The authors suggested that although the detection rate of capsule endoscopy was superior, the procedures were complementary, and that an initial diagnostic capsule endoscopy might be followed by therapeutic double-balloon enteroscopy[4]. In a prospective study of patients with lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage, sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of CT angiography for detection of colonic angiodysplasia were 70%, 100%, 100% and 57%, respectively, using colonoscopy and conventional angiography as reference standards[5]. A prospective study reported the diagnostic yield for OGIB of capsule endoscopy and CT enteroclysis to be 50% and 12.5%, respectively[36]. In another prospective study, diagnostic yield for OGIB of capsule endoscopy and MR enteroclysis was 36% and 0%, respectively[37].

Capsule endoscopy, being relatively non-invasive, was a suitable investigation for this patient. CT angiography relies on an actively bleeding lesion to identify the bleeding site with the added advantage that CT scanning can visualize intra-mural and extra-intestinal disease. CT or MR enteroclysis use intravenous contrast and either neutral or positive ionic oral contrast delivered through a nasoenteric tube. The volume control distends the small bowel and the multi-sensor CT or MR with fine cuts provides sufficient detail to visualize intra-mural and extra-intestinal disease. Having more than one investigative procedure that use different methodologies increases the chances of success. There was overt and often profound gastrointestinal bleeding, making CT angiography a good candidate.

Once diagnosis is secured, then selection of a therapeutic approach is needed. This may indeed be challenging, balancing between risk and benefit in the context of the patient’s general state of health. In the situation of this patient, variceal bleeding of the small bowel seemed most likely. A triad of portal hypertension, hematochezia without hematemesis, and previous abdominal surgery characterizes small intestinal varices[8]. Prior abdominal surgery predisposes the development of ectopic varices in adhesions. Possible physiological explanation could be the network of fine communication between the posterior abdominal wall and the parietal surface of the viscera, arising in the embryo due to the juxtaposition of the developing systemic and visceral venous plexus[9]. The patient had previous hernia repair, therefore satisfying the above-mentioned triad characteristic of small intestinal varices.

Options available for the treatment of jejunal varices include surgery, transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt (TIPS), enteroscopy and percutaneous embolization. Surgical treatment options for small intestinal variceal bleed include resection of the affected area of bowel, direct ligation of the bleeding varix, and re-anastomosis or portosystemic shunt insertion, which are associated with significant risk in a patient with advanced cirrhosis. TIPS with or without trans-catheter embolization of the varices is an alternative to laparotomy in some cases[10]. Uncontrolled bleeding from ectopic varices located in rectum, colon, ileum, jejunum, duodenum, and stoma have been treated with TIPS successfully in 90% of patients[10], and this is the option recommended for prevention of rebleeding from gastric and ectopic varices (including intestinal, stomal, and anorectal varices) by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases[11].

As the patient had severe coagulopathy and extensive paraumbilical varices, surgery was deemed to be of high risk. He was not an optimal candidate for TIPS as he had portal vein thrombosis. Double-balloon enteroscopy was a suitable alternative, but this would have been a prolonged procedure, with increased technical difficulty posed by the expected large amount of blood in the small bowel. As such, percutaneous embolization was attempted first. Embolization using steel coils, gel foam, thrombin, collagen or autologous blood clot aims to occlude the feeding vein to the ectopic varices. Steel coils are available in a variety of sizes, allowing occlusion of large veins without difficulty, leading to a permanent focal occlusion, and are therefore the preferred embolic materials. Percutaneous embolization has been reportedly performed via the transjugular or transhepatic route. However, as he had portal vein thrombosis, these approaches were not straightforward. Unconventional approaches had to be considered. He had extensive caput medusae, and this provided us with an alternative and more direct access to the portal circulation.

The percutaneous paraumbilical embolization via caput medusae used to treat our patient has not been previously described, and could be a possible therapeutic option for cirrhotics with portal vein thrombosis and bleeding small intestinal varices not suitable for surgery. There is a case report of a patient with jejunal varices treated successfully with embolization[12]. A 79-year-old woman developed melena 2 years post-jejunal resection for a jejunal varix. Abdominal angiography revealed recurrence of the jejunal varix around the hepaticojejunostomy. She underwent a surgical procedure with intra-operative portography, and embolization of the jejunal varix. Our patient, in addition to having previous abdominal surgery, also had severe coagulopathy, which made any surgical approach a high risk procedure.

In summary, for this cirrhotic patient with portal vein thrombosis and previous abdominal surgery, ectopic jejunal varices were found to be the source of OGIB by the combination of CT angiography and capsule endoscopy. However, portal vein thrombosis precluded the recommended therapeutic choice, TIPS, and we used percutaneous embolization with coils via the paraumbilical approach as an unconventional and successful solution.

| 1. | Raju GS, Gerson L, Das A, Lewis B. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute technical review on obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1697-1717. |

| 2. | Spiller RC, Parkins RA. Recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding of obscure origin: report of 17 cases and a guide to logical management. Br J Surg. 1983;70:489-493. |

| 3. | Triester SL, Leighton JA, Leontiadis GI, Fleischer DE, Hara AK, Heigh RI, Shiff AD, Sharma VK. A meta-analysis of the yield of capsule endoscopy compared to other diagnostic modalities in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2407-2418. |

| 4. | Hadithi M, Heine GD, Jacobs MA, van Bodegraven AA, Mulder CJ. A prospective study comparing video capsule endoscopy with double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:52-57. |

| 5. | Junquera F, Quiroga S, Saperas E, Perez-Lafuente M, Videla S, Alvarez-Castells A, Miro JR, Malagelada JR. Accuracy of helical computed tomographic angiography for the diagnosis of colonic angiodysplasia. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:293-299. |

| 6. | Voderholzer WA, Ortner M, Rogalla P, Beinholzl J, Lochs H. Diagnostic yield of wireless capsule enteroscopy in comparison with computed tomography enteroclysis. Endoscopy. 2003;35:1009-1014. |

| 7. | Golder SK, Schreyer AG, Endlicher E, Feuerbach S, Scholmerich J, Kullmann F, Seitz J, Rogler G, Herfarth H. Comparison of capsule endoscopy and magnetic resonance (MR) enteroclysis in suspected small bowel disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:97-104. |

| 8. | Cappell MS, Price JB. Characterization of the syndrome of small and large intestinal variceal bleeding. Dig Dis Sci. 1987;32:422-427. |

| 9. | Edwards EA. Functional anatomy of the porta-systemic communications. AMA Arch Intern Med. 1951;88:137-154. |

| 10. | Vangeli M, Patch D, Terreni N, Tibballs J, Watkinson A, Davies N, Burroughs AK. Bleeding ectopic varices--treatment with transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt (TIPS) and embolisation. J Hepatol. 2004;41:560-566. |

| 11. | Boyer TD, Haskal ZJ. The role of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in the management of portal hypertension. Hepatology. 2005;41:386-400. |

| 12. | Sato T, Yasui O, Kurokawa T, Hashimoto M, Asanuma Y, Koyama K. Jejunal varix with extrahepatic portal obstruction treated by embolization using interventional radiology: report of a case. Surg Today. 2003;33:131-134. |