Published online Jan 21, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.349

Revised: December 10, 2008

Accepted: December 17, 2008

Published online: January 21, 2009

AIM: To investigate the relationship between post-endoscopic resection (ER) scars on magnifying endoscopy (ME) and the pathological diagnosis in order to validate the clinical significance of ME.

METHODS: From January, 2007 to June, 2008, 124 patients with 129 post-ER scar lesions were enrolled. Mucosal pit patterns on ME were compared with conventional endoscopy (CE) findings and histological results obtained from targeted biopsies.

RESULTS: CE findings showed nodular scars (53/129), erythematous scars (85/129), and ulcerative scars (4/129). The post-ER scars were classified into four pit patterns of sulci and ridges on ME: (I) 47 round; (II) 54 short rod or tubular; (III) 19 branched or gyrus-like; and (IV) 9 destroyed pits. Sensitivity and specificity were 88.9% and 62.5%, respectively, by the presence of nodularity on CE. Erythematous lesions were high sensitivity (100%), but specificity was as low as 36.7%. The range of the positive predictive value (PPV) on CE was as low as 10.6%-25%. Nine type IV pit patterns were diagnosed as tumor lesions, and 120 cases of type I-III pit patterns revealed non-neoplastic lesions. Thus, the sensitivity, specificity, and the PPV of ME were 100%.

CONCLUSION: ME findings can detect the presence of tumor in post-ER scar lesions, and make evident the biopsy target site in short-term follow-up. Further large-scale and long-term studies are needed to determine whether ME can replace endoscopic biopsy.

- Citation: Lee TH, Chung IK, Park JY, Lee CK, Lee SH, Kim HS, Park SH, Kim SJ, Cho HD, Hwangbo Y. Usefulness of magnifying endoscopy in post-endoscopic resection scar for early gastric neoplasm: A prospective short-term follow-up endoscopy study. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(3): 349-355

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i3/349.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.349

The use of magnifying endoscopy (ME) is now being reassessed since the successful study led by Professor Kudo regarding the utilization of magnifying colonoscopy[1]. Indeed, ME procedures for the upper gastrointestinal tract have been developed that make it possible to perform a variety of assessments, from routine observation to a detailed examination of squamous dysplasia, squamous-cell carcinoma, Barrett’s esophagus and associated dysplasia/early cancer, gastric cancer, and Helicobacter pylori infection[2–4]. ME with a narrow band image can aid in deciding the target of endoscopic biopsy for surveillance in Barrett’s esophagus[5–8]. The relationships between ME findings and gastric neoplastic histology, including the types of cancer detected, are now being investigated, and the usefulness of ME for diagnosing early gastric cancer has been reported[9–15].

Little data, however, are currently available regarding the correlation between the findings of ME and pathological findings in post-endoscopic resection (ER) scars. There has been no definitive endoscopic description of which endoscopic findings need endoscopic biopsy or where the endoscopist has to target the biopsy in altered large scar lesions. In addition, it remains controversial as to whether a biopsy should be performed for each endoscopy in patients who have already undergone complete ER. Thus, we have evaluated the relationship between the real-time diagnosis of post-ER scars observed by ME and the pathological diagnosis, thereby validating the clinical usefulness of ME as a follow-up method for post-ER scars in early gastric neoplasm.

From January, 2007 to June, 2008, a total of 143 lesions (138 patients) underwent endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) in our hospital (Cheonan Hospital, Soonchunhyang University). “En bloc resection” is defined as the resection of a single piece as opposed to piecemeal resection in multiple pieces. “Complete en bloc resection” is defined as a lesion being contained within the mucosal layer, with no lympho-vascular invasion, and all margins (deep and lateral) histologically demonstrated to be tumor-free.

Among 138 patients, 8 patients who had been revealed as incomplete ER were excluded because they received a subsequent operation. Other exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) refusal to participate in the study (3 cases); (2) recurrent tumorous lesions (1 case); (3) NSAIDs or anticoagulant drug users (2 cases). A total of 129 lesions (124 patients) were finally enrolled in this study. All patients provided written informed consent, and the clinical study was performed according to guidelines approved by the ethics committee of Soonchunhyang Cheonan Hospital. No patients were lost during follow-up.

For the endoscopic examination, we used a GIF-Q240Z video endoscope (Olympus Optical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) fitted with an optic-type zoom lens that provided up to 80 times magnification and a high-resolution color charge-coupled device (CCD) connected to a 14-inch monitor. A transparent tip attachment (D-201-11802; Olympus) projecting 2 mm from the endoscopic tip was pressed against the mucosa in order to maintain good focus. To decrease the influence of mucus in the stomach under magnified observation, all patients ingested simethicone (20-30 mL), and a mucolytic agent (10% N-acetylcysteine 20 to 30 mL) was sprayed on the mucosal surface[4]. Evaluation of the entire stomach was initially performed with conventional endoscopy (CE) to exclude obvious lesions and to define scar lesions. Next, with the endoscope positioned on the scar lesions, complete magnification was obtained, with particular attention being paid to minute surface architecture and arrangements. Following complete identification, targeted biopsy specimens of the scar lesions were obtained. Conventional and magnifying endoscopic procedures were performed by an endoscopist with 10 years endoscopic experience. All examinations and images were digitally stored and documented on commercially available videotapes. Classification and analysis of the magnified view were carried out using the photographs and recorded videos by another endoscopist who was blinded to the examinations and histopathologic results. When pit patterns were mixed, classification was based on the most prominent pattern. We performed an endoscopic biopsy on sites with prominent or higher grade pit patterns. Following ER, all patients were given a PPI (omeprazole 40 mg) for eight weeks. Conventional and magnifying endoscopies were performed with the targeted biopsy of all scar lesions two months after the ER.

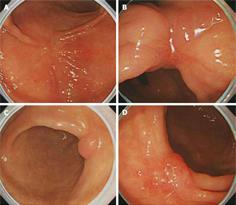

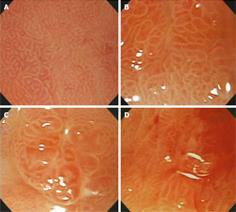

We classified CE characteristics of scar lesions according to the following attributes: height (elevated, flat, or depressed); nodularity (non-nodular or nodular); color (erythematous, pale, or iso-color with the surrounding mucosa); and ulceration (present or absent) (Figure 1). Next, the mucosal pit patterns in the post-ER scars were observed closely using ME. The mucosal pits were classified into four patterns of sulci and ridges: (I) round pit patterns; (II) short rod or tubular pit patterns; (III) branched or gyrus-like pit patterns; and (IV) destroyed pit patterns (Figure 2). The criteria for suspecting a tumorous lesion included the observation of a fundamentally destroyed pit pattern (Type IV).

The curative potential of en bloc resection was carefully evaluated histopathologically; slices were made at 2 mm intervals according to the Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma[16]. Following magnifying observation, standard histological assessment was performed with H&E staining. Lesions were classified into four groups for diagnostic purposes: non-neoplastic lesions, low-grade adenomas, high-grade adenomas, and carcinomas. These diagnostic criteria were based on the Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia[17]. The histological type and the degree of various pathologic findings were evaluated to determine the relationship between endoscopic findings such as foveolar hyperplasia, congestion of glands, atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and fibrosis. These findings were then classified and scored from 0 to 3, respectively (0 = normal, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe). A single pathologist who was blinded to the endoscopic findings reviewed and scored all the biopsy specimens. All pathologic findings were then compared in terms of both CE and ME findings.

Statistical evaluations were performed using SPSS statistical software, version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables and the ANOVA test was used to compare continuous variables. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Among 129 lesions, the method of ER was 104 ESD and 25 EMR. Complete resection was performed in 123 cases [117 en bloc resections (93 ESD and 24 EMR) and 6 piecemeal resections (2 ESD and 4 EMR)]. Six patients with incomplete resection who declined surgery were included in a follow-up endoscopic study. A set of 129 lesions from 124 patients were confirmed histologically by ER as consisting of 38 adenocarcinomas, 48 high-grade adenomas, and 43 low-grade adenomas. Following ER, the mean follow-up time was 2.27 ± 0.46 mo (mean ± SD) (Table 1).

| Parameter | |

| Case (Patient) | 129 (124) |

| Male | 79 |

| Female | 45 |

| Age, yr (SD) | 58.51 (11.27) |

| Male | 59.48 (11.79) |

| Female | 56.71 (10.13) |

| ER outcome | |

| ESD/EMR | 104/25 |

| Complete resection | 123 |

| En bloc | 117 |

| Piecemeal | 6 |

| Incomplete resection | 6 |

| Post-ER diagnosis | |

| Adenoma | 43 lesions |

| Adenoma with HGD | 48 lesions |

| Adenocarcinoma | 38 lesions |

| Follow up mo (SD) | 2.27 (0.46) |

The CE findings revealed the following results: 38 elevated, 79 flat, and 12 depressive-type scars; 76 non-nodular and 53 nodular scars; 85 erythematous and 44 pale or iso-colored scars; and 4 ulcerative scars. The minute surface structure of post-ER scars, as shown by ME, demonstrated four pit patterns of sulci and ridges. These pit patterns were classified according to the main pit pattern as follows: (I) 47 round pit patterns; (II) 54 short rod or tubular pit patterns; (III) 19 branched or gyrus-like pit patterns; and (IV) 9 destroyed pit patterns. There was no statistical significance between conventional endoscopic and ME findings (P > 0.05), although the presence of nodularity and erythematous lesions was high in type III or IV pit patterns on ME (P = 0.091, P = 0.079, respectively, Table 2).

| CE findings | Pit type (No.) | Total (129) | Pvalue | |||

| I (47) | II (54) | III (19) | IV (9) | |||

| Height | 0.205 | |||||

| Elevated | 14 | 20 | 3 | 6 | 38 | |

| Flat | 29 | 29 | 13 | 3 | 79 | |

| Depressed | 4 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 12 | |

| Nodularity | 0.091 | |||||

| Present | 17 | 18 | 11 | 6 | 53 | |

| Absent | 30 | 36 | 8 | 3 | 76 | |

| Color | 0.079 | |||||

| Erythematous | 30 | 31 | 16 | 8 | 85 | |

| Iso or pale | 17 | 23 | 3 | 1 | 44 | |

| Ulceration | 0.285 | |||||

| Present | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |

| Absent | 47 | 52 | 18 | 8 | 125 | |

Eight lesions revealed the presence of tumors in 53 cases with nodularity, while one lesion had no nodularity in the post-ER scar. Nine lesions revealed the presence of tumors in 85 cases with erythematous lesions. One lesion revealed the presence of tumors in 4 cases with non-healed ulcer lesions. Sensitivity and specificity were 88.9% and 62.5%, respectively, when the presence of nodularity aided in the detection of a neoplastic lesion on CE. Erythematous lesions had a high sensitivity (100%), but specificity was as low as 36.7%. The presence of an ulcer had low sensitivity (11.1%) and high specificity (97.5%). The range of the positive predictive value was as low as 10.6%-25% (Table 3). As assessed by CE, none of the mucosal height terms, color, nodularity, or ulceration showed statistical significances between various non-neoplastic pathologic features in post-ER scars.

| CE findings (No.) | Pathologic results | |||||

| Non-neoplastic | Neoplastic | Sensitivity (%) (95% CI) | Specificity (%) (95% CI) | PPV (%) (95% CI) | NPV (%) (95% CI) | |

| Presence of nodularity (53) | 45 | 8 | 88.9 (68.4-100) | 62.5 (53.8-71.2) | 15.1 (5.5-24.7) | 98.7 (96.1-100) |

| Erythematous lesion (85) | 76 | 9 | 100.0 | 36.7 (28.0-45.3) | 10.6 (4.0-17.1) | 100.0 |

| Presence of ulcer (4) | 3 | 1 | 11.1 (0.0-31.6) | 97.5 (94.7-100) | 25.0 (0.0-67.4) | 93.6 (89.3-97.9) |

| Total No. | 120 | 9 | ||||

Although there was no statistical significance in the relationship between endoscopic findings and other non-neoplastic pathologic findings, type III or IV pit patterns exhibited slightly higher histological scores in terms of gland congestion, intestinal metaplasia, and atrophy (P > 0.05, Table 4). Nine type IV pit patterns on ME were diagnosed as tumor lesions, pathologically, and 120 cases of type I-III pit patterns revealed non-neoplastic lesions without tumor lesions. Thus, the sensitivity, specificity, and the positive predictive value were 100%, 100% and 100%, respectively (Table 5). Six cases were noted in patients who had received incomplete resection. Three cases of piecemeal resection for early gastric cancer were diagnosed as tumor lesions in spite of histologically complete resection.

| Pit type | Foveolar hyperplasia | Gland congestion | Intestinal metaplasia | Atrophy | Fibrosis |

| I | 0.96 | 0.64 | 1.09 | 1.11 | 0.21 |

| II | 0.96 | 0.48 | 1.11 | 1.11 | 0.19 |

| III | 0.84 | 0.79 | 1.05 | 1.26 | 0.11 |

| IV (coexisting findings with tumor) | 0.78 | 0.89 | 1.33 | 1.56 | 0.33 |

| P value1 | 0.837 | 0.244 | 0.828 | 0.34 | 0.644 |

Magnifying colonoscopy has already been reported as a clinically useful tool for diagnosing colorectal tumors[118]. Furthermore, ME has been confirmed as being superior to conventional colonoscopy with respect to its predictive power for diagnosing pathological neoplasms detected during endoscopy. Technological improvements in recent years have demonstrated that ME can identify the fine mucosal patterns of the gastrointestinal tract, and it is now evident that the findings obtained from this new procedure correlate positively with histological findings[1920], and that ME can help determine the target biopsy site during surveillance in Barrett’s esophagus[5–8]. Despite these advances, however, there have been few studies investigating whether ME is capable of improving the rate of prediction for pathological diagnosis of gastric scar lesions after ER in early gastric neoplasm beyond that of the conventional method. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first description in the English literature of magnifying endoscopic classification and the characteristic definition of gastric post-ER scar lesions which includes comparative pathology for both magnifying and conventional procedures.

Diagnosis of early gastric cancer relies on macroscopic findings by CE, namely flat, elevated, or depressed; color identical to the neighboring noncancerous area, red or pale; the presence of granules or nodules; the presence or absence of ulcers; and the presence or absence of fold conversions, among others[13]. During diagnostic endoscopy, the endoscopist usually takes routine biopsies from even inconspicuous lesions that appear slightly erythematous, discolored, flat, granular, or shallow depressed mucosal areas in the stomach[1421]. There has been no definitive description of which findings require endoscopic biopsy or where we have to target the biopsy in post-ER scar lesions in early gastric neoplasm. In our study, nodularity and erythematous lesions revealed the presence of tumors (sensitivity, 88.9% and 100%, respectively). One of 4 ulcer lesions revealed the presence of tumor (sensitivity, 11.1%). These CE findings were important in differentiating tumors in post-ER scars, but these findings in post-ER scar lesions are not specific to tumorous lesions (positive predictive value: 10.6-25.0%) in terms of diagnosing recurrence or suspected tumor in this study. Additionally, these findings give no specific information as to where we must target biopsies in certain large post-ER scar lesions. We cannot ignore endoscopic biopsy in cases with these endoscopic findings, which requires additional costs and is invasive in certain cases with no tumorous post-ER scar lesions.

Nevertheless, there is controversy regarding whether endoscopists should perform a biopsy during every follow-up study after complete ER. Recently, several endoscopists have suggested that short-term endoscopic examination is not necessary since complete ESD was introduced[22]. With recent advances in endoscopic skill and equipment, gastric neoplasms can be resected more completely by ESD, a technique that can produce larger and safer margins around the tumor compared to conventional EMR, thus making the rate of tumor recurrence very low. Recent ESD results have achieved greater than 95% en bloc resection as well as excellent survival rates[2324]. In short-term follow-up endoscopic examinations in post-ER scars, the presence of a tumor can be considered residual tumor rather than the recurrence of a new tumor when we consider the doubling time of early gastric neoplasm.

Using ME, we classified post-ER scar lesions according to the fine gastric mucosal pit patterns of sulci and ridges as follows: (I) round pit patterns; (II) short rod or tubular pit patterns; (III) branched or gyrus-like pit patterns; and (IV) destroyed pit patterns. Non-tumorous lesions in post-ER scars included type I, II, and III pit patterns, and none of these pit patterns were identified as histologically discernable tumorous lesions in our study. All the tumor lesions were noted in post-ER scar lesions with the type IV pattern. Our results suggest that the ME pattern may be considered a useful diagnostic tool capable of replacing the more invasive technique of endoscopic biopsy or identifying the target biopsy site in cases with mixed pit patterns.

Although there was no statistical significance in the relationship between endoscopic findings and other non-neoplastic pathologic findings, type III or IV pit patterns exhibited slightly higher histological scores in terms of gland congestion, intestinal metaplasia, and atrophy. High scores with regard to gland congestion may play a role in the regeneration process, and high scores with regard to the other two findings may be suspected in relation to pathology near the original gastric neoplasm before ER. We were unable to evaluate whether these findings demonstrated a tendency toward tumor development. A longitudinal long-term follow-up study is needed to determine the significance of these non-neoplastic pathologic findings, and a large-scale study is needed to assess the relationship between these pathologic findings and the presence of tumors in post-ER scar lesions.

In this study, none of the patients who had been treated with complete en bloc resection by ESD had the type IV pattern, and no tumor lesions were observed pathologically in these patients. Nine tumor lesions were noted in cases with incomplete resection (6 cases) and piecemeal resection by EMR (3 cases). Consequently, we believe that ME will be useful in predicting the pathological diagnosis of tumorous lesions in post-ER scars, especially after incomplete or piecemeal resection. Furthermore, compared with CE, ME might be a useful alternative to biopsies, especially for short-term follow-up after complete en bloc resection by ESD.

There were, however, some limitations to our study: (1) we focused on the simple characteristics of the mucosal pit structures of scar lesions at 2 mo after ER. We could not evaluate the vascular pattern and the validity of various pathologic findings using our short-term results. In addition, we need a long-term follow up study to confirm the final histology in lesions shown to be non-neoplastic in nature with type I-III pit patterns. (2) We enrolled only nine cases with type IV pit pattern because the therapeutic outcome of ER is excellent in gastric neoplasms. We could not discuss the diagnostic accuracy overall but could only do so in the nine cases with type IV pit pattern. A larger study with more cases to obtain a statistically meaningful accuracy is required in order to detect tumor recurrence in scar lesions following ER. (3) In terms of our procedure, the use of a transparent cap limited our survey capacity because it produced a narrow window of view and was very time consuming. After these procedural handicaps are overcome, large-scale and longitudinal follow-up studies should be pursued.

In conclusion, ME findings can detect the presence of tumors through detailed classification of post-ER scar lesions. ME may also help in decision-making regarding whether to perform biopsies and in identifying the target biopsy site in the short-term follow-up of post-ER scars in early gastric neoplasm. As stated above, however, further large-scale and long-term studies are required to determine whether ME can replace endoscopic biopsy.

Magnifying endoscopy (ME) is now being used in the diagnosis of various gastrointestinal diseases. However, not much data is currently available regarding the correlation between the findings on ME and pathological findings on post-endoscopic resection (ER) scars. There has been no definitive endoscopic description of which endoscopic findings require endoscopic biopsy or where the endoscopist should target the biopsy in altered large scar lesions.

In this study, the authors demonstrate the relationship between the real-time diagnosis of post-ER scars observed using ME and the pathological diagnosis, thereby validating the clinical usefulness of ME as a follow-up method for post-ER scars in early gastric neoplasm.

This study gives the first description in the English literature of ME classification and the characteristic definition of gastric post-ER scar lesions. In addition, it includes comparative pathology for both the magnifying and conventional findings. Furthermore, our study suggests that ME can detect the presence of tumors through pit classification and may help in decision-making regarding the target biopsies in the short-term follow-up of post-ER scars.

By providing an understanding of how ME permits visualization of post-ER scars, this study may represent a future strategy in the short-term follow-up of post-ER scars in early gastric neoplasm.

The mucosal pits, which were magnified up to 80 times with ME, were classified into four patterns of sulci and ridges: (I) round pit patterns; (II) short rod or tubular pit patterns; (III) branched or gyrus-like pit patterns; and (IV) destroyed pit patterns. The criteria for suspecting a tumorous lesion included the observation of primarily a destroyed pit pattern.

The authors investigated the pit patterns of post-ER scars using ME in early gastric neoplasm. It was revealed that all tumor lesions noted were in the type IV pit pattern. The results suggest that the ME pit patterns may be considered a useful diagnostic tool capable of replacing the more invasive endoscopic biopsy or of locating the target biopsy site in cases with mixed pit patterns, and may also help in the decision-making regarding whether to perform biopsies in the short-term follow-up of post-ER scars in early gastric neoplasm.

| 1. | Kudo S, Tamura S, Nakajima T, Yamano H, Kusaka H, Watanabe H. Diagnosis of colorectal tumorous lesions by magnifying endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:8-14. |

| 2. | Endo T, Awakawa T, Takahashi H, Arimura Y, Itoh F, Yamashita K, Sasaki S, Yamamoto H, Tang X, Imai K. Classification of Barrett's epithelium by magnifying endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:641-647. |

| 3. | Sharma P. Magnification endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:435-443. |

| 4. | Dinis-Ribeiro M, da Costa-Pereira A, Lopes C, Lara-Santos L, Guilherme M, Moreira-Dias L, Lomba-Viana H, Ribeiro A, Santos C, Soares J. Magnification chromoendoscopy for the diagnosis of gastric intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:498-504. |

| 5. | Singh R, Anagnostopoulos GK, Yao K, Karageorgiou H, Fortun PJ, Shonde A, Garsed K, Kaye PV, Hawkey CJ, Ragunath K. Narrow-band imaging with magnification in Barrett's esophagus: validation of a simplified grading system of mucosal morphology patterns against histology. Endoscopy. 2008;40:457-463. |

| 6. | Kara MA, Ennahachi M, Fockens P, ten Kate FJ, Bergman JJ. Detection and classification of the mucosal and vascular patterns (mucosal morphology) in Barrett's esophagus by using narrow band imaging. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:155-166. |

| 7. | Kara MA, Bergman JJ. Autofluorescence imaging and narrow-band imaging for the detection of early neoplasia in patients with Barrett's esophagus. Endoscopy. 2006;38:627-631. |

| 8. | Kara MA, Peters FP, Rosmolen WD, Krishnadath KK, ten Kate FJ, Fockens P, Bergman JJ. High-resolution endoscopy plus chromoendoscopy or narrow-band imaging in Barrett's esophagus: a prospective randomized crossover study. Endoscopy. 2005;37:929-936. |

| 9. | Yao K, Oishi T, Matsui T, Yao T, Iwashita A. Novel magnified endoscopic findings of microvascular architecture in intramucosal gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:279-284. |

| 10. | Yoshida T, Kawachi H, Sasajima K, Shiokawa A, Kudo SE. The clinical meaning of a nonstructural pattern in early gastric cancer on magnifying endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:48-54. |

| 11. | Tamai N, Kaise M, Nakayoshi T, Katoh M, Sumiyama K, Gohda K, Yamasaki T, Arakawa H, Tajiri H. Clinical and endoscopic characterization of depressed gastric adenoma. Endoscopy. 2006;38:391-394. |

| 12. | Yagi K, Aruga Y, Nakamura A, Sekine A, Umezu H. The study of dynamic chemical magnifying endoscopy in gastric neoplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:963-969. |

| 13. | Otsuka Y, Niwa Y, Ohmiya N, Ando N, Ohashi A, Hirooka Y, Goto H. Usefulness of magnifying endoscopy in the diagnosis of early gastric cancer. Endoscopy. 2004;36:165-169. |

| 14. | Tajiri H, Doi T, Endo H, Nishina T, Terao T, Hyodo I, Matsuda K, Yagi K. Routine endoscopy using a magnifying endoscope for gastric cancer diagnosis. Endoscopy. 2002;34:772-777. |

| 15. | Areia M, Amaro P, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Cipriano MA, Marinho C, Costa-Pereira A, Lopes C, Moreira-Dias L, Romaozinho JM, Gouveia H. External validation of a classification for methylene blue magnification chromoendoscopy in premalignant gastric lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:1011-1018. |

| 16. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma-2nd English Edition. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10-24. |

| 17. | Schlemper RJ, Riddell RH, Kato Y, Borchard F, Cooper HS, Dawsey SM, Dixon MF, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Flejou JF, Geboes K. The Vienna classification of gastrointestinal epithelial neoplasia. Gut. 2000;47:251-255. |

| 18. | Koba I, Yoshida S, Fujii T, Hosokawa K, Park SH, Ohtsu A, Oda Y, Muro K, Tajiri H, Hasebe T. Diagnostic findings in endoscopic screening of superficial colorectal neoplasia: results from a prospective study. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1998;28:542-545. |

| 19. | Yagi K, Nakamura A, Sekine A. Comparison between magnifying endoscopy and histological, culture and urease test findings from the gastric mucosa of the corpus. Endoscopy. 2002;34:376-381. |

| 20. | Cales P, Oberti F, Delmotte JS, Basle M, Casa C, Arnaud JP. Gastric mucosal surface in cirrhosis evaluated by magnifying endoscopy and scanning electronic microscopy. Endoscopy. 2000;32:614-23. |

| 21. | Tajiri H, Ohtsu A, Boku N, Muto M, Chin K, Matsumoto S, Yoshida S. Routine endoscopy using electronic endoscopes for gastric cancer diagnosis: retrospective study of inconsistencies between endoscopic and biopsy diagnoses. Cancer Detect Prev. 2001;25:166-173. |

| 22. | Nakajima T, Oda I, Gotoda T, Hamanaka H, Eguchi T, Yokoi C, Saito D. Metachronous gastric cancers after endoscopic resection: how effective is annual endoscopic surveillance? Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:93-98. |

| 23. | Lee IL, Wu CS, Tung SY, Lin PY, Shen CH, Wei KL, Chang TS. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancers: experience from a new endoscopic center in Taiwan. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:42-47. |

| 24. | Oda I, Saito D, Tada M, Iishi H, Tanabe S, Oyama T, Doi T, Otani Y, Fujisaki J, Ajioka Y. A multicenter retrospective study of endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:262-270. |