Published online Aug 7, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3704

Revised: June 13, 2009

Accepted: June 20, 2009

Published online: August 7, 2009

We report a case of primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) of the liver. A 17-year-old man with a solid mass in the anterior segment of the right liver was asymptomatic with negative laboratory examinations with the exception of positive HBV. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) revealed a hypervascular lesion in the arterial phase and hypoechoic features during the portal and late phases. However, enhanced spiral computed tomography (CT) showed hypoattenuation in all three phases. Following biopsy, immunohistochemical evaluation demonstrated positive CD117. Different imaging features of primary GISTs of the liver are due to pathological properties and different working systems between CEUS and enhanced spiral CT.

- Citation: Luo XL, Liu D, Yang JJ, Zheng MW, Zhang J, Zhou XD. Primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(29): 3704-3707

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i29/3704.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.3704

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) is an uncommon tumor and can be seen mostly in gastrointestinal tract origin[1]. Sporadic primary GISTs unrelated to the tubular gastrointestinal tract, such as the omentum, mesentery or retroperitoneum, gallbladder, uterus and liver[1–4], have been reported suggesting that these tumors are more widespread than commonly appreciated. Herein, we report a case of primary GIST of the liver evaluated by contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) and enhanced spiral computed tomography (CT) with histological and immunohistochemical diagnosis.

A 17-year-old man, who was a HBV carrier without symptoms, was found to have a mass in the anterior segment of the right liver lobe by B-mode ultrasound examination at a local hospital and was then transferred to our hospital. Abdominal physical examination found no palpable mass. Laboratory studies showed positive HBsAg, HBe-Ab as well as HBc-Ab, and negative HBs-Ab, HBeAg, HCV, CEA, AFP, CA 19-9, CA 12-5, and CA 15-3. Blood chemistry was normal except for an alanine aminotransferase level of 60 U/L which was slightly increased. The fecal occult blood test was negative. Chest X-ray was also negative.

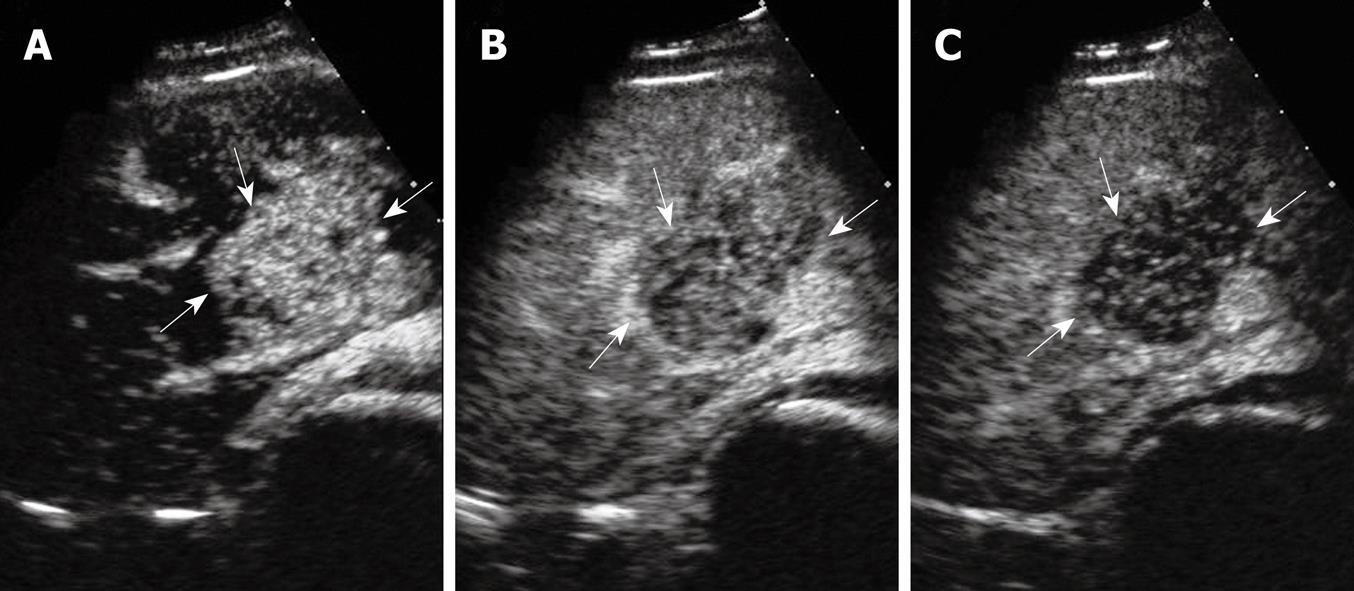

On CEUS examination using a 3.5 MHz convex transducer and a harmonic tissue program (Sequia 512, Acuson Corporation, USA), a solid, oval-shaped, hyperechogenic 5.1 cm × 3.8 cm × 4.6 cm mass in the anterior segment of the right lobe next to the liver hilum was detected, showing vascularization on color Doppler imaging. Contrast-enhanced sonography with pulse inversion sequence imaging was performed which showed contrast enhancement in the lesion appeared 14 s after a bolus injection of 2.4 mL SonoVue® (Bracco Diagnosis, Italy) and peaked at 27 s. Contrast enhancement subsequently decayed 30 s after injection to the end of the delay phase and the lesion was hypoechoic compared with that of the adjacent liver parenchyma (Figure 1).

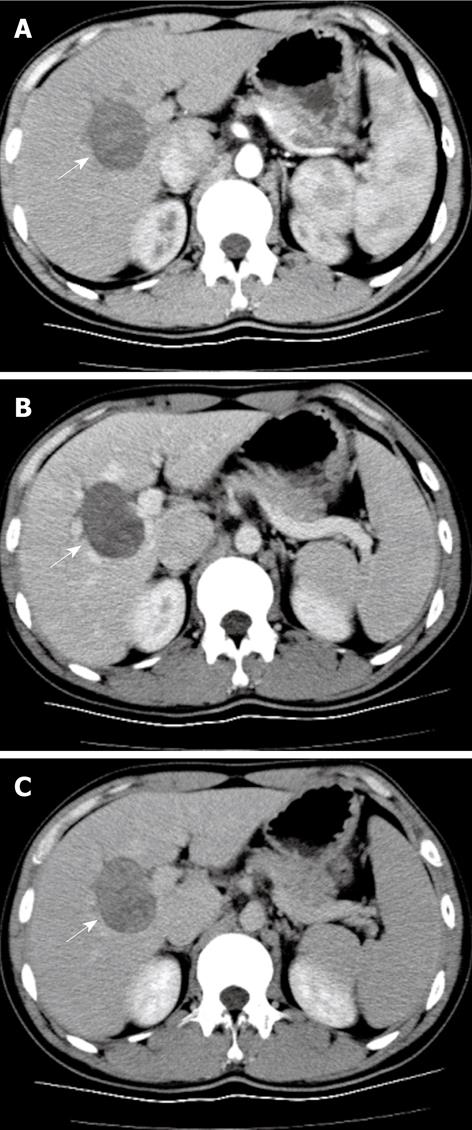

Enhanced spiral CT (Aquilion, 16-slice, Toshiba, Japan) was performed 2 wk after CEUS and sequential triple-phase scanning began 20 s after 80 mL Iopromide (Ultravist, Schering, Berlin, Germany), an iodinated contrast, was injected at a flow rate of 3 mL/s. A hypo-density mass was demonstrated in the right liver lobe with slight enhancement in the arterial phase, which gradually increased in the portal phase and reached a maximum in the late phase (Figure 2).

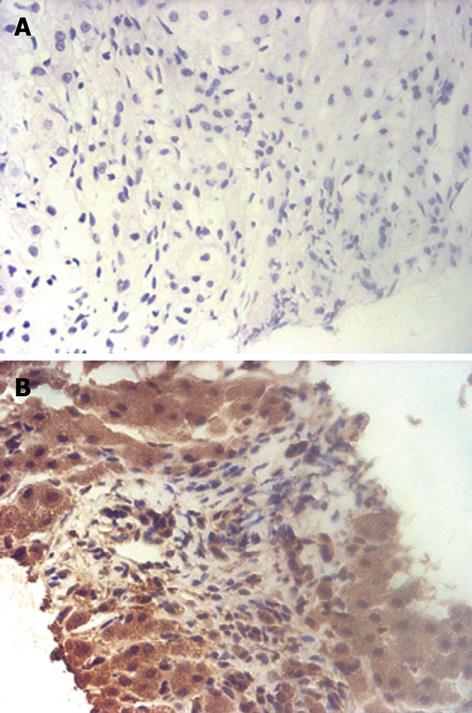

Thereafter, biopsy was performed under the guidance of ultrasound. Histologic examination of the biopsy specimen showed that the tumor consisted of irregular neoplastic spindle cells and no mitoses were found (Figure 3A). Immunohistological staining showed positive reactivity for CD117 (Figure 3B), vimentin and CD34, and staining for keratin, HHF35, a-SMA, desmin, NF and S-100 was negative. With no other findings in the abdominal and pelvic cavity on CEUS and enhanced spiral CT studies, the final diagnosis of a GIST originating from the liver was made. The patient was subsequently treated with radiofrequency ablation therapy. CEUS examination 3 mo later demonstrated no vascularity in the tumor.

GIST is one of the soft tissue sarcomas arising from a pacemaker cell known as the interstitial cell of Cajal[5], and can be seen mostly in gastrointestinal tract origin but predominantly occurs in the stomach (60% to 70%) and small intestine (25% to 35%), with rare occurrences in the colon and rectum (5%), esophagus (< 2%) and appendix[1]. GISTs originating from outside the gastrointestinal tract are extremely unusual. Regardless of where they occur, almost all GISTs have the same biologic behavior with the expression of the c-kit (CD117) protein, which is a growth factor transmembrane receptor with tyrosine kinase activity and differentiates these tumors from other mesenchymal tumors[1–4].

The diagnosis of GIST mainly depends on histologic and immunohistochemical appearance, usually after surgery. GIST is mainly composed of spindle cells, which are randomly arranged in a variety of patterns. Immunohistochemical profiles show positivity for CD117, CD34, and vimentin; however, they are usually negative for keratin, S-100 protein, and smooth muscle actin. Tumor size and mitotic counts are used as prognostic factors, and mitotic counts exceeding 5 per 50 high power fields or size larger than 5 cm can predict future recurrence or metastasis to other areas with a predilection for the liver or the peritoneal cavity[16]. In our case, the histologic and immunohistochemical findings strongly supported the diagnosis of GIST. Owing to the fact that almost all GISTs in the liver are malignant, and metastatic lesions usually arise from the gastrointestinal tract, we carefully scanned the abdominal and pelvic cavities and showed no other positive findings. In addition, no mitoses were noted on pathological evaluation. The final diagnosis was primary GIST of the liver which was hypothesized to originate from progenitors of mesenchymal cells capable of differentiation toward a pacemaker cell phenotype[34]. The tumor was graded as low-grade malignant GIST due to its size.

Imaging modalities play an important role in detecting tumor localization, staging tumor status, assessing response to treatment and in monitoring tumor recurrence following treatment. Imaging features have revealed that the majority of GISTs manifest themselves as having an exophytic and cavitary nature with heterogeneous enhancement of contrast agents[67]. In Vanel’s[6] report, 13 cases of hepatic metastases from GISTs were heterogeneous hypodense lesions with progressive, concentric enhancement. In our case, hypoattenuation with a gradual contrast enhancement pattern on enhanced spiral CT was coincident with those of metastatic GISTs of the liver. However, hypervascularity with quick wash-in and wash-out on CEUS resembled malignant tumors of the liver, and because the patient was a HBV carrier, the initial diagnosis was highly suspicious for hepatocellular carcinoma. An analogous case appeared in Nicolau’s report[8], where the CEUS pattern in one benign solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) presented as arterial enhancement with quick wash-out in the portal and late phases which led to the misdiagnosis of a malignant tumor. It is worth noting that SFT is also one of the soft tissue sarcomas which are thought to have many clinical and pathologic features in common and the tumors are generally rich in vasculature even in benign stages[910].

Although imaging findings did not seem to be a determinant factor in the diagnosis of this case, when the medical records were reviewed some clues were revealed. In this patient, a solitary parenchymatous tumor was found in the liver, with negative tumor markers on laboratory testing and no other findings on medical examination except positivity for HBV. This implied that it would be necessary to make a differential diagnosis from a relatively large spectrum of tumors. It should be borne in mind that some soft tissue sarcomas, such as GISTs, have prominent vascular features and the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the contrast agent entering these types of tumors may be similar to those in malignant tumors.

Discrepancies between CEUS and enhanced spiral CT may be due to the distinct vascular architecture of GISTs and different working systems existing in the two imaging modalities. Contrast enhancement in CT or MR imaging can not be performed in real-time. Single frames are obtained during each of the phases of the liver. The time window of contrast-enhanced CT to image the liver lesion during the hepatic arterial-dominant phase is so short (approximately 20-30 s) that it results in the possibility of missing the early arterial enhancement. Since CEUS performed in real-time has the ability to continuously evaluate the entire arterial, portal, and late phases, if a lesion shows rapid changing enhancement, it is possible that this change in enhancement may be better visualized in CEUS than in contrast enhanced CT or MR imaging in the early phase. In Murphy-Lavallee’s[11] studies, most hepatic metastases, including those thought to be hypovascular, showed transient arterial hypervascularity followed by rapid and complete wash-out within the conventional arterial phase on CEUS. The time to peak arterial enhancement of these tumors ranged from 8 to 27 s, and the beginning of wash-out ranged from 13 to 50 s.

Conclusively, primary GIST of the liver is extremely rare. Despite some discordance between CEUS and enhanced spiral CT in our case, their imaging features still seem to mimic those of the malignant tumors of the liver, irrespective of whether they are primary or metastatic lesions. To date, there are only two cases of primary GIST of the liver reported in the English literature, and to our knowledge, the case presented here is the first report of both CEUS and enhanced spiral CT evaluations before the final diagnosis. The present case may be taken as a warning for future clinical practice.

| 1. | Miettinen M, Majidi M, Lasota J. Pathology and diagnostic criteria of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs): a review. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38 Suppl 5:S39-S51. |

| 2. | Wingen CB, Pauwels PA, Debiec-Rychter M, van Gemert WG, Vos MC. Uterine gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST). Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97:970-972. |

| 3. | Hu X, Forster J, Damjanov I. Primary malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:1606-1608. |

| 4. | De Chiara A, De Rosa V, Lastoria S, Franco R, Botti G, Iaffaioli VR, Apice G. Primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver with lung metastases successfully treated with STI-571 (imatinib mesylate). Front Biosci. 2006;11:498-501. |

| 5. | Kindblom LG, Remotti HE, Aldenborg F, Meis-Kindblom JM. Gastrointestinal pacemaker cell tumor (GIPACT): gastrointestinal stromal tumors show phenotypic characteristics of the interstitial cells of Cajal. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1259-1269. |

| 6. | Vanel D, Albiter M, Shapeero L, Le Cesne A, Bonvalot S, Le Pechoux C, Terrier P, Petrow P, Caillet H, Dromain C. Role of computed tomography in the follow-up of hepatic and peritoneal metastases of GIST under imatinib mesylate treatment: a prospective study of 54 patients. Eur J Radiol. 2005;54:118-123. |

| 7. | Wong CT, Lee YW, Ho LWC, Pay KH, Huang HYH. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours of the small bowel-computed tomographic appearance, angiographic features, and potential pitfalls in digital subtraction angiography. J HK Coll Radiol. 2002;5:197-201. |

| 8. | Nicolau C, Vilana R, Catalá V, Bianchi L, Gilabert R, García A, Brú C. Importance of evaluating all vascular phases on contrast-enhanced sonography in the differentiation of benign from malignant focal liver lesions. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:158-167. |

| 9. | Cormier JN, Pollock RE. Soft tissue sarcomas. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:94-109. |

| 10. | van Roggen JF, Hogendoorn PC. Solitary fibrous tumour: the emerging clinicopathologic spectrum of an entity and its differential diagnosis. Curr Diagn Pathol. 2004;10:229-235. |

| 11. | Murphy-Lavallee J, Jang HJ, Kim TK, Burns PN, Wilson SR. Are metastases really hypovascular in the arterial phase? The perspective based on contrast-enhanced ultrasonography. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:1545-1556. |