Published online Aug 7, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3653

Revised: July 3, 2009

Accepted: July 10, 2009

Published online: August 7, 2009

AIM: To identify the factors associated with participation in gastric cancer screening programs.

METHODS: Using data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005 (KNHANES III), a nationwide health-related survey in Korea, a cross-sectional study was performed to investigate the multiple factors associated with gastric cancer screening attendance among persons aged at least 40 years. The study population included 4593 individuals who completed a gastric cancer screening questionnaire and had no previous cancer history. Four groups of individual-level or environmental level covariates were considered as potential associated factors.

RESULTS: Using KNHANES III data, an estimated 31.71% of Korean individuals aged at least 40 years adhered to gastric cancer screening recommendations. Subjects who graduated from elementary school [adjusted odds ratio (aOR), 1.66; 95% CI: 1.21-2.26], middle/high school (aOR, 1.38; 95% CI: 1.01-1.89), and university or higher (aOR, 1.64; 95% CI: 1.13-2.37) were more likely to undergo gastric cancer screening than those who received no formal education at all. The population with the highest income tertile had more attendance at gastric screening compared to those with the lowest income tertile (aOR, 1.36; 95% CI: 1.06-1.73). Gastric screening was also negatively associated with excessive alcohol consumption (aOR, 0.71; 95% CI: 0.53-0.96). A positive attitude to preventive medical evaluation was significantly associated with better participation in gastric cancer screening programs (aOR, 5.26; 95% CI: 4.35-6.35).

CONCLUSION: Targeted interventions for vulnerable populations and public campaigns about preventive medical evaluation are needed to increase gastric cancer screening participation and reduce gastric cancer mortality.

- Citation: Kwon YM, Lim HT, Lee K, Cho BL, Park MS, Son KY, Park SM. Factors associated with use of gastric cancer screening services in Korea. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(29): 3653-3659

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i29/3653.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.3653

Gastric cancer is a major public health burden. Although the worldwide incidence of gastric cancer and associated mortality is decreasing, gastric cancer is still the fourth most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related death, causing 700 000 deaths annually[1]. In contrast to the worldwide trend, in Korea the incidence of gastric cancer has been reported to be stable or increasing, and is still one of the most common forms of cancer and one of the leading causes of death from cancer among both sexes[23]. According to the Korea Central Cancer Registry Data, gastric cancers comprised 18% of all new cancers and caused 15.3% of cancer deaths in 2005.

Despite the increasing incidence of gastric cancer in Korea, mortality due to gastric cancer is decreasing. This is due to advances in surgical techniques, chemotherapy and radiological therapy, and to early detection by gastric cancer screening programs[4]. Because patients with early-stage gastric cancer often show no clinical symptoms, a significant proportion of patients are diagnosed when the disease is at an advanced stage, which is associated with poor prognosis. If screening for gastric cancer were universal, beginning at the age of 40 years, and combined with timely treatment of surgical or endoscopic mucosal removal of early cancers, the gastric cancer mortality rate could be markedly reduced[56]. A recent study in Korea also showed that repeated endoscopic screening within 2 years decreased the incidence of gastric cancer and endoscopic resection could be applied to more patients who underwent EGD screening within 2 years[7].

In the past decade, the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW) agency has established multiple cancer control programs. In 1996, the Korean government initiated a comprehensive “10-year plan for cancer control”. As part of this program, the Korean Government initiated the National Cancer Screening Program (NCSP) in 1999. Since then, the NCSP has provided free cancer screening for common cancers to low-income individuals receiving medical aid[8]. However, the rate of participation in gastric cancer screening programs is not optimal[910]. Therefore, to increase the participation rate and improve the survival rate of gastric cancer patients, identification and removal of potential barriers to cancer screening participation might be of great importance. However, few studies have investigated the individual and environmental predictors of gastric cancer screening participation in the Korean population.

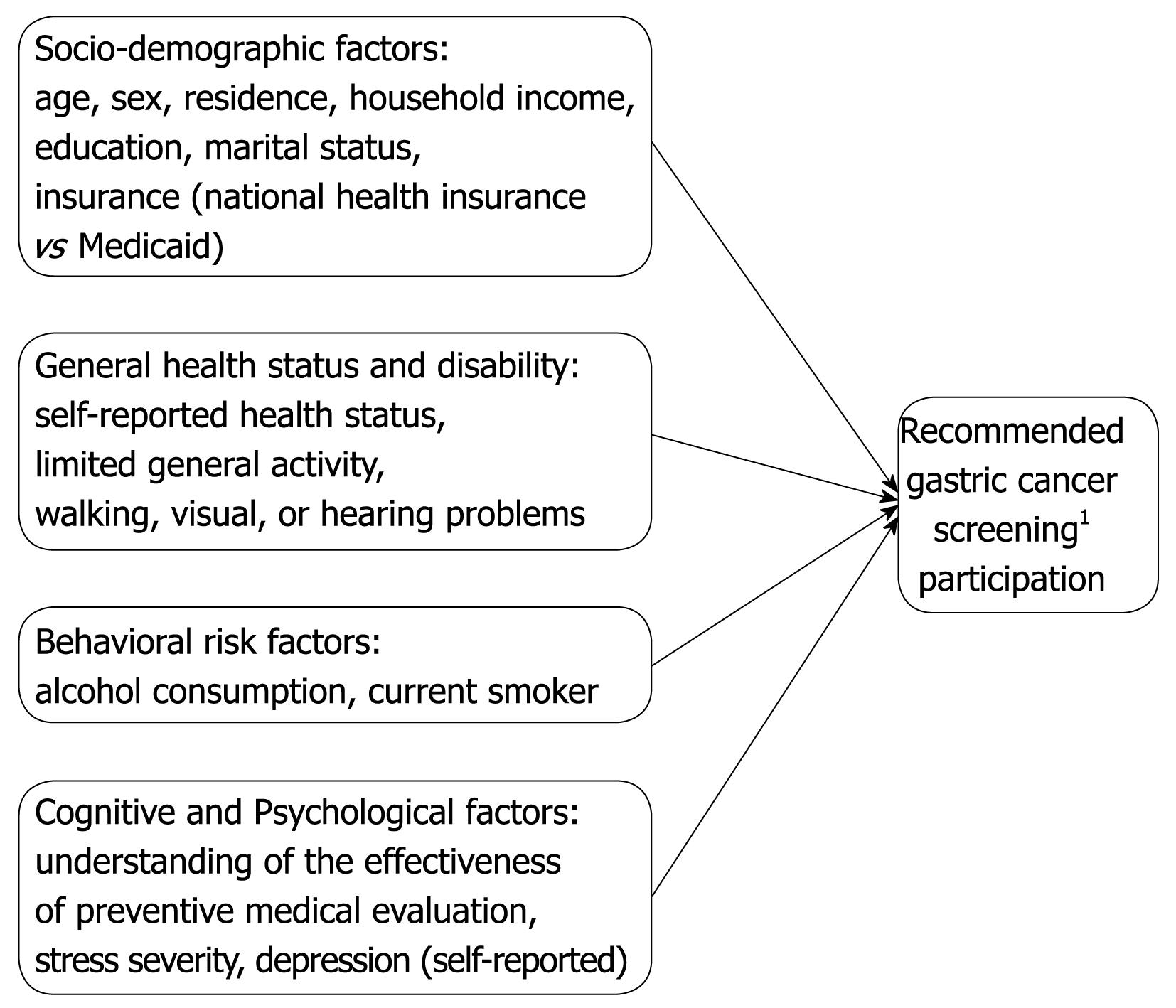

In the present study, we analyzed the relationship among four dimensions of individual-level factors, including socio-demographic characteristics, general health status, gastric cancer risk factors and cognitive factors, and gastric cancer screening participation (Figure 1), among individuals included in the Third Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005 (KNHANES III).

This study was based on data obtained from the KNHANES III. The KNHANES is a national household survey that provides comprehensive information on health status, health care utilization, and socio-demographics of a nationally representative sample of 34 145 individuals from 13 800 households. The KNHANES III is composed of four parts: health interview survey, health behavior survey, health examination survey and nutrition survey.

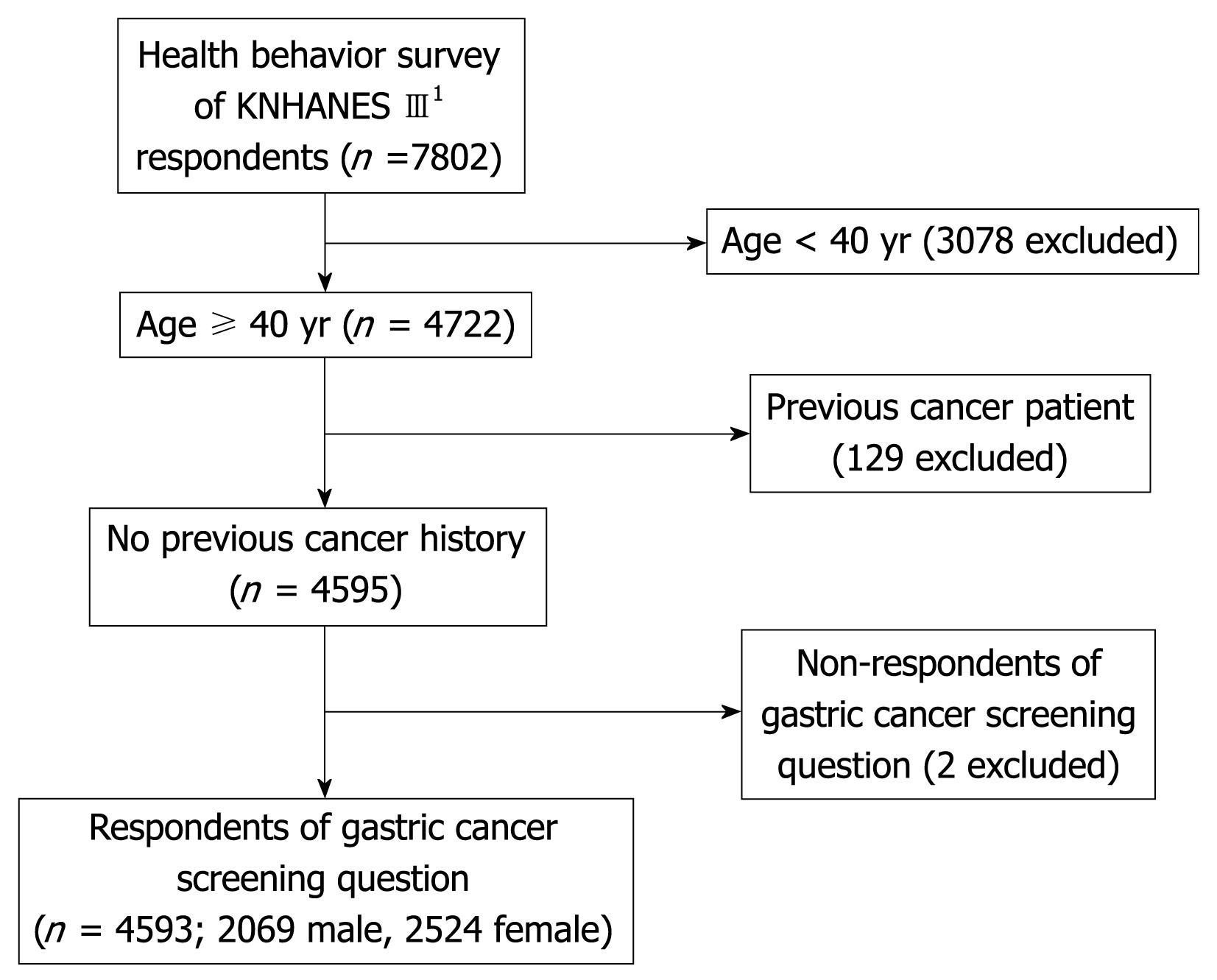

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of data from the 7802 individuals who completed the health behavior survey. We then selected individuals aged at least 40 years who answered the gastric cancer screening behavior question, yielding 4722 individuals. After excluding 129 individuals who had previously been diagnosed with cancer, 4593 people (2069 men and 2524 women) were eligible for our analyses (Figure 2).

According to the KNCSP guidelines, persons aged at least 40 years should undergo gastroscopy or upper gastrointestinal series (UGIS) examinations every 2 years. Subjects were asked the question “when was the last time you had a gastric cancer screening examination (endoscope or UGIS)?” The possible responses were “never”, “less than 1 year”, “1-2 years”, “more than 2 years”.

In the present study, the outcome variable is whether the individuals adhere to KNCSP guidelines or not. We recognized that individuals who reported never taking a gastric cancer screening examination or having undergone examinations more than 2 years prior to completing the questionnaire would be classified as not adhering to KNCSP guidelines.

Data about variables were also obtained from the KNHANES III and their associations with gastric cancer screening were investigated. We considered 17 variables as potential factors that could be associated with gastric cancer screening (Figure 1); these 17 variables were classified into one of four groups: (1) socio-demographic factors [age, gender, residential area (metropolitan area or not), household income, education level, marital status, insurance (national health insurance or Medicaid)]; (2) general health status and disability (self-reported health status, limitation of general activity, walking problem, visual problem, hearing problem; (3) gastric cancer risk factors (alcohol consumption, current smoker); (4) cognitive and psychological factors (attitude to routine health checks, stress severity, depression).

Patients were stratified by age; age 40-49, 50-59, 60-69 and ≥ 70 years. Residential area was classed as metropolitan or non-metropolitan area. Income was calculated by dividing the household monthly income by the square root of the household size (equivalized income), and was categorized into three groups[1112]. Education level was categorized as uneducated, elementary school graduate, high school graduate, and college or higher education graduate. Marital status was recorded as married, unmarried, widowed, or divorced, and was dichotomized as living with or without spouse. South Korea has a universal health insurance system; hence we compared individuals with national health insurance (NHI) and those receiving Medicaid (the Korean government program for low-income or medically needy individuals).

Alcohol consumption was assessed using the question “how often do you binge drink?” (binge drinking was defined as seven or more drinks for men and five or more drinks for women), and was categorized into three groups: (1) non-binge drinker, nondrinker or social drinker who reported binge drinking no more than once per mouth; (2) binge drinker, reported binge drinking 1-4 times per month; and (3) frequent binge drinker, reported binge drinking more than twice per week[13]. Individuals were asked “Do you now smoke cigarettes?” and, based on responses, were categorized by smoking status into three groups: (1) never smoker, have never smoked; (2) ex-smoker, have quit smoking; and (3) current smoker, smoke daily or intermittently smoke.

For cognitive and psychological factors, we considered attitudes to preventive medical evaluation, stress severity and self-reported depression.

The dependent variable of interest was whether the patient had undergone gastric cancer screening within the previous 2 years; independent variables were the 17 factors described above.

Descriptive statistical methods were used to describe the basic characteristics of the study population; numbers and percentages are reported for each variable. First, to identify the factors associated with undergoing gastric cancer screening, we used univariate logistic regression analysis. Odds ratios and confidence intervals for the associations between gastric cancer screening attendance and each factor were calculated. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered significant. Next, the factors identified as significantly associated with gastric cancer screening by univariate analysis (P < 0.05) were analyzed by multivariate logistic regression analysis. All statistical tests were performed using STATA, version 10.0.

Characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. In the study population, 1457 individuals (31.71%) had undergone a gastric cancer screening examination within the previous 2 years. The mean age of our study population was 55.12 years; 54.95% were women. Three-quarters of the population were living with a spouse and most were enrolled in the national health insurance program. Of the study population, 8.69% were frequent binge drinkers, consuming large quantities of alcohol almost daily. A total of 6.30% of women were current smokers, compared with 48.77% of men; this result is similar to that reported for adult men in Korea in 2006 (44.7%)[8].

| n (%) | ||

| Socio-demographic factor | ||

| Age (yr) | 40-49 | 1854 (40.37) |

| 50-59 | 1204 (26.21) | |

| 60-69 | 924 (20.12) | |

| ≥ 70 | 611 (13.3) | |

| Sex | Male | 2069 (45.05) |

| Female | 2524 (54.95) | |

| Residence1 | Metropolis | 2058 (44.81) |

| Town or country | 2535 (55.22) | |

| Household income2 | Lowest tertile | 1446 (31.88) |

| Middle tertile | 1550 (34.17) | |

| Highest tertile | 1540 (33.95) | |

| Education | Uneducated | 497 (10.83) |

| Elementary school | 1117 (24.32) | |

| Middle-high school | 2206 (48.03) | |

| University or higher | 773 (16.83) | |

| Marital status3 | Without spouse | 1053 (22.94) |

| With spouse | 3537 (77.06) | |

| National health insurance (NHI) vs Medicaid4 | NHI | 4355 (95.17) |

| Medicaid | 221 (4.83) | |

| General health status | ||

| Self-reported health status | Healthy | 1522 (33.14) |

| Middle | 1682 (36.62) | |

| Unhealthy | 1389 (30.24) | |

| Limitation of general activity | Limited | 671 (14.61) |

| Unlimited | 3922 (85.39) | |

| Walking problem | Limited | 881 (19.19) |

| Unlimited | 3711 (80.81) | |

| Visual problem | Limited | 1600 (34.84) |

| Unlimited | 2993 (65.16) | |

| Hearing problem | Limited | 635 (13.83) |

| Unlimited | 3958 (86.17) | |

| Cancer risk factor | ||

| Smoking | Never | 2536 (55.21) |

| Ex-smoker | 889 (19.36) | |

| Current smoker | 1168 (25.43) | |

| Alcohol consumption (number of binge drinking sessions per month)5 | Non-binge drinker | 2781 (60.55) |

| Binge drinker | 1413 (30.76) | |

| Frequent binge drinker | 399 (8.69) | |

| Psychological factors | ||

| Gastric cancer screening6 | Participated | 1457 (31.72) |

| Did not participate | 3136 (68.28) | |

| Attitude to health check-up | Not effective7 | 1730 (15.46) |

| Effective | 2862 (84.54) | |

| Stress severity | None | 845 (18.4) |

| Mild | 2126 (46.29) | |

| Moderate | 1311 (28.54) | |

| Severe | 311 (6.77) | |

| Depression (self-reported) | No | 3788 (82.49) |

| Yes | 804 (17.51) |

Table 2 shows the univariate analysis results; crude odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were reported. The factors associated with gastric cancer screening participation were age (more than 70 years), income, education level, marital status, limited general activity, visual problems, smoking status, attitude to preventive medical health assessments, stress and alcohol consumption.

| OR (crude) | 95% CI | ||

| Socio-demographic factor | |||

| Age (yr) | 40-49 | 1 (ref) | |

| 50-59 | 1.07 | 0.89-1.29 | |

| 60-69 | 0.99 | 0.80-1.22 | |

| ≥ 70 | 0.61 | 0.47-0.79 | |

| Sex | Male | 1 (ref) | |

| Female | 0.95 | 0.84-1.07 | |

| Residence | Metropolis | 1 (ref) | |

| Town or country | 1.15 | 0.96-1.36 | |

| Household income | Lowest tertile (≤ 1.00 × 106 kW) | 1 (ref) | |

| Middle tertile (1.00-2.42 × 106 kW) | 1.25 | 1.03-1.53 | |

| Highest tertile (≥ 2.45 × 106 kW) | 1.80 | 1.47-2.20 | |

| Education | Uneducated | 1 (ref) | |

| Elementary school | 1.83 | 1.38-2.43 | |

| Middle or high school | 1.71 | 1.31-2.26 | |

| University or higher | 2.51 | 1.84-3.46 | |

| Marital status | Without spouse | 1 (ref) | |

| With spouse | 1.42 | 1.20-1.68 | |

| NHI vs Medicaid | NHI | 1 (ref) | |

| Medicaid | 0.98 | 0.66-1.45 | |

| General health status | |||

| Self-reported health status | Healthy | 1 (ref) | |

| Middle | 1.07 | 0.91-1.27 | |

| Unhealthy | 1.09 | 0.92-1.29 | |

| Limitation of general activity | Limited | 1 (ref) | |

| Unlimited | 1.20 | 1.00-1.45 | |

| Walking problem | Limited | 1 (ref) | |

| Unlimited | 1.15 | 0.96-1.39 | |

| Visual problem | Limited | 1 (ref) | |

| Unlimited | 1.15 | 1.00-1.32 | |

| Hearing problem | Limited | 1 (ref) | |

| Unlimited | 1.16 | 0.97-1.39 | |

| Cancer risk factor | |||

| Alcohol consumption | Non-binge drinker | 1 (ref) | |

| Binge drinker | 1.03 | 0.89-1.20 | |

| Frequent binge drinker | 0.76 | 0.59-0.98 | |

| Smoking | Never | 1 (ref) | |

| Ex-smoker | 1.05 | 0.88-1.24 | |

| Current smoker | 0.80 | 0.69-0.94 | |

| Psychological factor | |||

| Attitude to health check-up | No | 1 (ref) | |

| Yes (cancer screening is effective) | 5.61 | 4.66-6.75 | |

| Stress severity | None | 1 (ref) | |

| Mild | 1.18 | 0.99-1.41 | |

| Moderate | 1.23 | 1.01-1.49 | |

| Severe | 0.95 | 0.72-1.24 | |

| Depression (self-reported) | No | 1 (ref) | |

| Yes | 1.03 | 0.87-1.23 |

By multivariate logistic regression analysis, only four of these factors were significantly and independently associated with gastric cancer screening (Table 3): household monthly income, education level, alcohol consumption and attitude to preventive medical evaluation.

| Multivariate OR | 95% CI | ||

| Socio-demographic factor | |||

| Age (yr) | 40-49 | 1 (ref) | |

| 50-59 | 1.02 | 0.83-1.25 | |

| 60-69 | 0.95 | 0.74-1.23 | |

| ≥ 70 | 0.82 | 0.59-1.16 | |

| Household income | Lowest tertile (≤ 1.00 × 106 kW) | 1 (ref) | |

| Middle tertile (1.00-2.42 × 106 kW) | 1.08 | 0.86-1.36 | |

| Highest tertile (≥ 2.45 × 106 kW) | 1.36 | 1.06-1.73 | |

| Education | Uneducated | 1 (ref) | |

| Elementary school | 1.66 | 1.21-2.26 | |

| Middle or high school | 1.38 | 1.01-1.89 | |

| University or higher | 1.64 | 1.13-2.37 | |

| Marital status | Without spouse | 1 (ref) | |

| With spouse | 1.05 | 0.87-1.26 | |

| General health status | |||

| Limitation of general activity | Limited | 1 (ref) | |

| Unlimited | 0.95 | 0.76-1.19 | |

| Visual problem | Limited | 1 (ref) | |

| Unlimited | 1.03 | 0.88-1.21 | |

| Cancer risk factor | |||

| Alcohol consumption | Non-binge drinker | 1 (ref) | |

| Binge drinker | 0.93 | 0.77-1.13 | |

| Frequent binge drinker | 0.71 | 0.53-0.96 | |

| Currently smoking | Never | 1 (ref) | |

| Ex-smoker | 1.08 | 0.87-1.33 | |

| Current smoker | 0.86 | 0.70-1.06 | |

| Psychological factor | |||

| Attitude to health check-up | No | 1 (ref) | |

| Yes (cancer screening is effective) | 5.26 | 4.35-6.35 | |

| Stress severity | None | 1 (ref) | |

| Mild | 1.06 | 0.87-1.30 | |

| Moderate | 1.20 | 0.98-1.48 | |

| Severe | 1.06 | 0.80-1.41 |

Of the socio-demographic factors considered, higher household income was found to be associated with a higher OR. Compared with the lowest income tertile, the adjusted OR (aOR) of the highest income tertile was 1.36 (95% CI: 1.06-1.73). There was also a clear trend to increased rates of gastric cancer screening with greater education level (elementary school graduate: aOR, 1.66; 95% CI: 1.21-2.26; middle or high school graduate: aOR, 1.38; 95% CI: 1.01-1.89; university or higher education graduate: aOR, 1.64; 95% CI: 1.13-2.37).

Analysis of gastric cancer risk factors revealed that frequent binge drinkers who consumed more than seven glasses of Soju (70 g alcohol in total), the most widely consumed traditional beverage in Korea, per day more than twice per week were significantly less likely to undergo gastric cancer screening compared with non-binge drinkers or binge drinkers (aOR, 0.71; 95% CI: 0.53-0.96).

A positive attitude to preventive medical evaluation showed the greatest association with gastric cancer screening participation. Individuals who recognized the effectiveness of preventive medical evaluation were more likely to undergo recommended gastric cancer screening compared with those who did not (aOR, 5.26; 95% CI: 4.35-6.35).

In this national representative household survey, we found that the participation rate of gastric cancer screening in Korea amongst individuals aged 40 years or more, is only 31.71%, even though gastric cancer is largely treatable when detected at an early stage. Our study also found that low household income, low education level, frequent binge drinking and a negative attitude to preventive medical evaluation were significantly associated with poor participation in gastric cancer screening programs. Our study is the first to use multivariate analysis to identify the factors associated with gastric cancer screening in clinical practice, including demographic factors, general health status, behavioral risk factors and psychological factors.

Factors associated with unhealthy behavior, such as alcohol consumption and smoking, are considered gastric cancer risk factors[14–17], and high levels of tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption have been shown to substantially increase the relative risk of this cancer[15]. Therefore, preventive measures, such as gastroscopy or UGIS, are likely to be of particular benefit in frequent binge drinkers and smokers. However, in this study, we found that frequent binge drinkers were less likely to undergo gastric cancer screening tests compared with others. Current smokers also showed a low participation rate in screening programs, although the difference compared with non-smokers was not significant. These findings indicate that more interventions are needed for individuals with unhealthy behavioral risk factors, and suggest that successful preventive measures could markedly reduce the number of gastric cancer deaths.

Our study also showed that a positive attitude to the effectiveness of preventive medical evaluation is strongly associated with gastric cancer screening participation. Previously, several studies have demonstrated that cognitive elements can directly affect the decision to undergo gastric cancer screening, and personal background and other socio-demographic factors might have indirect effects through their effects on cognitive variables[918]. These findings indicate that improved public education about the benefits of preventive cancer screening and routine health checks could have important influences on individual patient decisions to undergo gastric cancer screening.

Household income and education level were shown to be significant predictors of participation in gastric cancer screening in the present study. Previous studies have reported inconsistencies in the relative strength and significance of the correlations between cancer screening and socio-demographic factors[1918–21]. There are several possible reasons for this inconsistency. One possibility is that physiologic medical accessibility may vary with health care policy and location; for example, developed vs non-developed countries or urban vs rural area. Therefore, the study location and health policy status should be considered when different studies are compared. Another possible reason is the differences in study design. Several recent reports in Korea have highlighted the factors associated with cancer screening participation, but showed no associations between gastric cancer screening and socio-economic factors[918]. This can be explained by the differences in study design, such as variable categories and outcome variable. In the present study, we used equivalized household income which was calculated by dividing the household monthly income by the square root of the household size, while other previous studies usually did not consider the household size and simply used the crude household income[9]. In addition, a major focus of one study was the intention to receive gastric cancer screening, not receipt of gastric cancer screening, which could lead to different results from our study[18].

The Korean Government initiated the National Cancer Screening Program (NCSP) in 1999, and it has since expanded its target population. Currently, NCSP provides Medical Aid recipients and NHI beneficiaries within the lower 50% income bracket with free gastric cancer screening services[8].

In addition, the costs of gastric cancer screening in Korea are low compared with other countries, which could improve the accessibility of these services to low-income individuals[22]. However, our results indicate that socio-economic inequalities in gastric cancer screening participation have not yet been sufficiently overcome. To increase gastric cancer screening participation, improved intervention programs for individuals with low income and education level are needed.

No general health status or disability-related factor was significantly associated with gastric cancer screening participation, which is in contrast to our original hypothesis that there might be disability-related barriers to participation in screening programs. A recent cross-sectional study reported that individuals with a disability showed reduced levels of participation in mass screening programs compared with those without a disability[23]. However, few studies have assessed the association between physical disability and gastric cancer screening participation. Further research about gastric cancer screening patterns among individuals with a disability is required to determine these associations.

Our study has several limitations. First, as the findings were based on patient self-reported health status data, respondents may under-report, over-report, or choose not to respond, leading to possible inaccuracy. Second, information about gastric cancer screening was obtained from the responses to a single question, and any symptoms at the time of the examination were not reported. Cancer screening prevention programs are designed for individuals with no associated symptoms; therefore, there could be some misclassification of gastric cancer screening participation by including individuals with symptoms indicative of gastric cancer. However, previous studies have also not considered accompanying symptoms, and used a similar definition of cancer screening participation[212425].

In conclusion, we found that more than two-thirds of the Korean population did not comply with the gastric cancer screening recommendations. These findings indicate that there is scope for further improvement. In particular, targeted interventions are needed for vulnerable populations such as those with low income, low education level and unhealthy behaviors. In addition, public campaigns to improve attitudes to preventive medical evaluation could be powerful methods to increase gastric cancer screening participation.

The mortality of gastric cancer is decreasing despite the increasing incidence in Korea. This can be explained by surgical technique development and early detection by endoscopic screening or upper gastrointestinal study.

Despite the development in national cancer control programs, the rate of participation in gastric cancer screening programs is still not optimal. However, few studies have investigated the individual and environmental predictors of gastric cancer screening participation in the Korean population. In this study, the authors identified the factors associated with participation in gastric cancer screening programs.

Recent reports in Korea have highlighted the factors associated with cancer screening participation, but reported inconsistencies in the results. It can mainly be explained by the differences in study design, that is, different variable categories and outcome variables. Our study shows predictors associated with gastric cancer screening in multiple dimensions, both at the individual level and at the environmental level.

The authors’ findings indicate that targeted interventions and public campaigns for vulnerable populations could be powerful methods to increase gastric cancer screening participation.

In the present study, authors have performed a cross-sectional study investigating the factors associated with participation in a gastric cancer screening program in Korea, and multivariate analyses have revealed independent predictive factors to be household income, education, alcohol consumption and attitude to health check-up. The manuscript is relatively well written, and the results are moderately interesting.

| 1. | Crew KD, Neugut AI. Epidemiology of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:354-362. |

| 2. | Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2007. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:43-66. |

| 3. | Shin HR, Won YJ, Jung KW, Kong HJ, Yim SH, Lee JK, Noh HI, Lee JK, Noh HI, Lee JK. Nationwide cancer incidence in Korea, 1999-2001: first result using the National Cancer Incidence Database. Cancer Res Treat. 2005;37:325-331. |

| 4. | Hosokawa O, Miyanaga T, Kaizaki Y, Hattori M, Dohden K, Ohta K, Itou Y, Aoyagi H. Decreased death from gastric cancer by endoscopic screening: association with a population-based cancer registry. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:1112-1115. |

| 5. | Hyung WJ, Kim SS, Choi WH, Cheong JH, Choi SH, Kim CB, Noh SH. Changes in treatment outcomes of gastric cancer surgery over 45 years at a single institution. Yonsei Med J. 2008;49:409-415. |

| 6. | Barreda B F, Sanchez L J. [Endoscopic Submucosal dissection and mucosectomy for the treatment of the epithelial neoplasia and early gastric cancer]. Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2008;28:332-355. |

| 7. | Nam SY, Choi IJ, Park KW, Kim CG, Lee JY, Kook MC, Lee JS, Park SR, Lee JH, Ryu KW. Effect of repeated endoscopic screening on the incidence and treatment of gastric cancer in health screenees. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:855-860. |

| 8. | Yoo KY. Cancer control activities in the Republic of Korea. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008;38:327-333. |

| 9. | Bae SS, Jo HS, Kim DH, Choi YJ, Lee HJ, Lee TJ, Lee HJ. [Factors associated with gastric cancer screening of Koreans based on a socio-ecological model]. J Prev Med Public Health. 2008;41:100-106. |

| 10. | Sung NY, Park EC, Shin HR, Choi KS. [Participation rate and related socio-demographic factors in the national cancer screening program]. J Prev Med Public Health. 2005;38:93-100. |

| 11. | Jang SN, Cho SI, Hwang SS, Jung-Choi K, Im SY, Lee JA, Kim MK. [Trend of socioeconomic inequality in participation in cervical cancer screening among Korean women]. J Prev Med Public Health. 2007;40:505-511. |

| 12. | Khang YH, Kim HR. [Socioeconomic mortality inequality in Korea: mortality follow-up of the 1998 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data]. J Prev Med Public Health. 2006;39:115-122. |

| 13. | LaBrie JW, Pedersen ER, Tawalbeh S. Classifying risky-drinking college students: another look at the two-week drinker-type categorization. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:86-90. |

| 14. | Shimazu T, Tsuji I, Inoue M, Wakai K, Nagata C, Mizoue T, Tanaka K, Tsugane S. Alcohol drinking and gastric cancer risk: an evaluation based on a systematic review of epidemiologic evidence among the Japanese population. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008;38:8-25. |

| 15. | Sjödahl K, Lu Y, Nilsen TI, Ye W, Hveem K, Vatten L, Lagergren J. Smoking and alcohol drinking in relation to risk of gastric cancer: a population-based, prospective cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:128-132. |

| 16. | Correa P, Piazuelo MB, Camargo MC. The future of gastric cancer prevention. Gastric Cancer. 2004;7:9-16. |

| 17. | Koizumi Y, Tsubono Y, Nakaya N, Kuriyama S, Shibuya D, Matsuoka H, Tsuji I. Cigarette smoking and the risk of gastric cancer: a pooled analysis of two prospective studies in Japan. Int J Cancer. 2004;112:1049-1055. |

| 18. | Hahm MI, Choi KS, Park EC, Kwak MS, Lee HY, Hwang SS. Personal background and cognitive factors as predictors of the intention to be screened for stomach cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2473-2479. |

| 19. | Kwak MS, Park EC, Bang JY, Sung NY, Lee JY, Choi KS. [Factors associated with cancer screening participation, Korea]. J Prev Med Public Health. 2005;38:473-481. |

| 20. | Han CH, Rhee CW, Sung SW, Kim YS, Cheon KS, Hoang HH, Jung TH, Jun TH. The factors related to the screening of stomach cancer. J Korean Acad Fam Med. 2001;22:528-538. |

| 21. | Welch C, Miller CW, James NT. Sociodemographic and health-related determinants of breast and cervical cancer screening behavior, 2005. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2008;37:51-57. |

| 22. | Gauld R, Ikegami N, Barr MD, Chiang TL, Gould D, Kwon S. Advanced Asia's health systems in comparison. Health Policy. 2006;79:325-336. |

| 23. | Park JH, Lee JS, Lee JY, Gwack J, Park JH, Kim YI, Kim Y. Disparities between persons with and without disabilities in their participation rates in mass screening. Eur J Public Health. 2009;19:85-90. |

| 24. | Fukuda Y, Nakamura K, Takano T. Reduced likelihood of cancer screening among women in urban areas and with low socio-economic status: a multilevel analysis in Japan. Public Health. 2005;119:875-884. |

| 25. | Lian M, Schootman M, Yun S. Geographic variation and effect of area-level poverty rate on colorectal cancer screening. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:358. |