Published online Jul 14, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3303

Revised: May 2, 2009

Accepted: May 9, 2009

Published online: July 14, 2009

AIM: To optimize the preoperative diagnosis and surgical management of adult intussusception (AI).

METHODS: A retrospective review of the clinical features, diagnosis, management and pathology 41 adult patients with postoperative diagnoses of intussusception was conducted.

RESULTS: Forty-one patients with 44 intussusceptions were operated on, 24.4% had acute symptoms, 24.4% had subacute symptoms, and 51.2% had chronic symptoms. 70.7% of the patients presented with intestinal obstruction. There were 20 enteric, 15 ileocolic, eight colocolonic and one sigmoidorectal intussusceptions. 65.9% of intussusceptions were diagnosed preoperatively using a computed tomography (CT) scan (90.5% accurate) and ultrasonography (60.0% accurate, rising to 91.7% for patients who had a palpable abdominal mass). Coloscopy located the occupying lesions of the lead point of ileocolic, colocolonic and sigmoidorectal intussusceptions. Four intussusceptions in three patients were simply reduced. Twenty-one patients underwent resection after primary reduction. There was no mortality and anastomosis leakage perioperatively. Except for one patient with multiple small bowel adenomas, which recurred 5 mo after surgery, no patients were recurrent within 6 mo. Pathologically, 54.5% of the intussusceptions had a tumor, of which 27.3% were malignant. 9.1% comprised nontumorous polyps. Four intussusceptions had a gastrojejunostomy with intestinal intubation, and four intussusceptions had no organic lesion.

CONCLUSION: CT is the most effective and accurate diagnostic technique. Colonoscopy can detect most lead point lesions of non-enteric intussusceptions. Intestinal intubation should be avoided.

- Citation: Wang N, Cui XY, Liu Y, Long J, Xu YH, Guo RX, Guo KJ. Adult intussusception: A retrospective review of 41 cases. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(26): 3303-3308

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i26/3303.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.3303

Intussusception is defined as the telescoping of a segment of the gastrointestinal tract into an adjacent one. Intussusception is uncommon in adults compared with the pediatric population. It is estimated that only 5% of all intussusceptions occur in adults and approximately 5% of bowel obstructions in adults are the result of intussusception[1]. Adult intussusception (AI) often presents with nonspecific symptoms. Preoperative diagnosis remains difficult and the extent of resection, and whether the intussusception, should be reduced remains controversial[1]. The present study reviews our experience of AI, and discusses the optimal preoperative diagnosis and surgical management techniques.

The medical records of 41 adult patients (18 years of age and older) with a postoperative diagnosis of intussusception at the First Affiliated Hospital, China Medical University, from January 2001 to August 2008, were collected. The clinical features, diagnosis, management and pathology of the 41 patients were reviewed.

An intussusception that involved only the jejunum or ileum was considered an enteric intussusception. An intussusception that involved the ileum and the colon was designated an ileocolic intussusception. An intussusception that involved only the colon was considered a colocolonic intussusception and one that involved the sigmoid colon and rectum was considered a sigmoidorectal intussusception[1]. A proximal segment of the bowel telescoped into the lumen of the adjacent distal segment was defined as antegrade intussusception. A distal segment of the bowel telescoped into the lumen of the adjacent proximal segment was defined as retrograde intussusception[2].

Acute symptoms were defined as < 4 d, subacute symptoms were defined as 4-14 d, and chronic symptoms were defined as > 14 d[3].

Intussusception was preoperatively diagnosed by abdominal ultrasonography with the target and doughnut signs on transverse view and the pseudokidney sign in the longitudinal view[1]. Intussusception was preoperatively diagnosed by multi-slice spiral computed tomography (CT) scans with the characteristic target or sausage sign, edematous bowel wall and mesentery in the lumen[45].

Of all the 41 patients, there were 18 males with an average age of 41.3 (15-71) and 23 females with an average age of 47.0 (18-87). The male:female ratio was 1:1.3. Three (7.3%) patients had two intussusceptions. In all, 44 intussusceptions were diagnosed, of which 20 were enteric intussusceptions (45.5%), 15 were ileocolic intussusceptions (34.1%), eight were colocolonic intussusceptions (18.2%) and one was a sigmoidorectal intussusception (2.3%). Forty-three intussusceptions were antegrade (97.7%) and only one enteric intussusception was retrograde (2.3%) (Table 1).

| Age (yr) | Sex | US1 | CT1 | Histopathology | Type | Reduction2 | Surgery |

| 23 | M | - | N | Small intestine hamartoma | Ileocolic | Y | Small intestine segmental resection |

| 58 | F | - | - | Intestinal inflammatory disease | Enteric | F | Small intestine segmental resection |

| 41 | M | N | - | Small intestine polyp | Ileocolic | F | Right hemicolectomy |

| 46 | F | N | Y | - (Mobile cecum) | Ileocolic | Y | Appendectomy, immobilization of the cecum |

| 54 | F | Y | - | Ascending colon adenocarcinoma | Colocolonic | N | Right hemicolectomy |

| 34 | F | Y | - | - Efferent Loop of Gastrojejunostomy with Tube | Enteric | Y | - |

| 29 | M | N | - | - | Enteric (retrograde) | Y | - |

| 20 | M | N | Y | GIST of small intestine | Ileocolic | Y | Right hemicolectomy |

| 22 | F | Y | - | Small intestine lipoma | Ileocolic | Y | Small intestine segmental resection |

| 38 | M | Y | - | Small intestine polyp | Enteric | F | Small intestine segmental resection |

| 48 | F | - | Y | Necrosis with bleeding | Enteric | F | Small intestine segmental resection |

| 48 | M | Y | Y | Suppurative appendicitis | Ileocolic | N | Right hemicolectomy |

| 41 | F | Y | - | GIST of small intestine | Ileocolic | Y | Small intestine segmental resection |

| 38 | M | Y | Y | Inflammation and ulcer of cecum | Ileocolic | Y | Right hemicolectomy |

| 64 | F | - | - | Small Intestine lipoma | Enteric | N | Small intestine segmental resection |

| 49 | F | Y | Y | - (After appendectomy) | Ileocolic | F | Right Hemicolectomy |

| 50 | M | N | - | Small intestine smooth muscle cell-derived borderline tumor | Enteric | Y | Small intestine segmental resection |

| 18 | F | N | - | Meckel diverticulum | Ileocolic | Y | Small intestine segmental resection |

| 45 | F | Y | Y | Small intestine malignant mesothelioma | Enteric | Y | Small intestine segmental resection |

| 49 | M | Y | Y | Small intestine polyp | Ileocolic | F | Right hemicolectomy |

| 39 | M | Y | Y | Cecum polyp | Colocolonic | Y | Right hemicolectomy |

| 33 | F | Y | - | Ileum adenoma with necrosis and bleeding | Ileocolic | N | Right hemicolectomy |

| 65 | M | - | - | Small intestine malignant Mesothelioma | Enteric | N | Small intestine segmental resection |

| 38 | M | N | Y | Colon Lipoma | Colocolonic | Y | Right hemicolectomy |

| 25 | F | - | - | Sigmoid Colon villous and tubular adenoma | Sigmoidorectal | Y | Partial resection of the sigmoid colon |

| 19 | M | Y | - | Mesenteric Lymphadenitis | Ileocolic | Y | Right hemicolectomy |

| 23 | F | N | N | Small Intestine Hamartoma | Enteric | Y | Small intestine segmental resection |

| 51 | F | - | Y | Colon Lipoma | Colocolonic | N | Right hemicolectomy |

| 24 | M | Y | - | Small and Large Intestine Multiple Adenomas | Enteric, Colocolonic | Y | Small intestine segmental resection and partial resection of the transverse colon |

| 41 | F | Y | - | Necrosis and Bleeding | Ileocolic | N | Right hemicolectomy |

| 64 | M | Y | Y | Ileum B Cell Malignant Lymphoma | Ileocolic | Y | Right hemicolectomy |

| 58 | F | N | Y | Ascending Colon Adenocarcinoma | Colocolonic | N | Right hemicolectomy |

| 56 | F | N | - | Intestinal Inflammatory Disease | Enteric | N | Right hemicolectomy |

| 43 | M | Y | - | - (Efferent Loop of Gastrojejunostomy with Tube) | Enteric, Enteric | Y | - |

| 87 | F | - | Y | Ascending Colon Adenocarcinoma | Colocolonic | N | Right hemicolectomy |

| 44 | M | - | Y | Small Intestine Multiple Adenomas Canceration | Enteric, Enteric | Y | Small intestine segmental resection |

| 40 | F | - | Y | Small Intestine Lipoma | Enteric | Y | Small intestine segmental resection |

| 51 | F | N | Y | GIST of Small Intestine | Enteric | Y | Small intestine segmental resection |

| 70 | F | Y | Y | - (Efferent Loop of Gastrojejunostomy with Tube) | Enteric | F | Small intestine segmental resection |

| 68 | F | - | Y | GIST of small Intestine | Enteric | Y | Small intestine segmental resection |

| 71 | M | N | - | Necrosis and Bleeding | Colocolonic | N | Left hemicolectomy |

Of the 41 patients, 95.1% (39/41) had abdominal pain, 26.8% (11/41) had bloody stool, and 34.1% (14/41) had a palpable abdominal mass. This classic pediatric presentation triad was only seen in 9.8% (4/41). 70.7% (29/41) presented with intestinal obstructions of various extents. The duration of the symptoms varied from six hours to three years; 24.4% (10/41) with acute symptoms, 24.4% (10/41) with subacute symptoms, and 51.2% (21/41) with chronic symptoms.

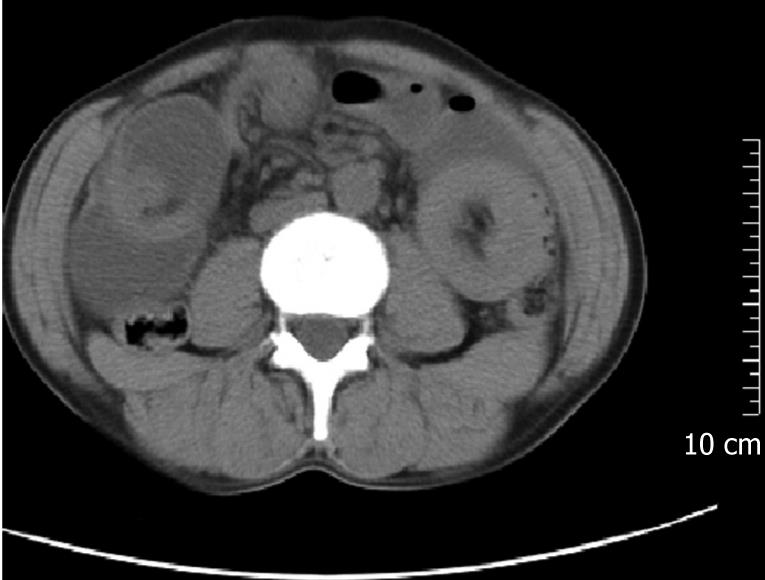

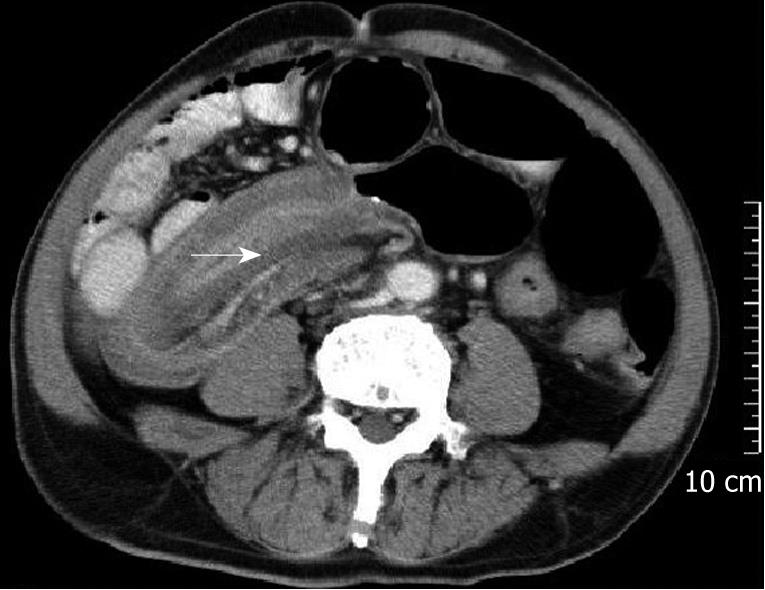

Of the 41 patients, 65.9% (27/41) were preoperatively diagnosed with intussusception. Thirty patients had ultrasonography, of which 18 were diagnosed with intussusception (60.0% accuracy). However, the preoperative diagnostic accuracy of the patients who had palpable abdominal masses was 91.7% (11/12). Twenty-one patients had helical CT scans, of which 19 were diagnosed with intussusception (90.5% accuracy) (see Table 1, Figures 1–4). None of the patients who had experienced gastrojejunostomy and underwent an upper gastrointestinal water-soluble contrast study, were diagnosed intussusception. One patient who had a small intestinal lipoma and underwent capsule endoscopy was diagnosed with regional mucosa puffiness. Eight patients underwent a colonoscopy. The etiologies were found in most of them by coloscopy (Table 2).

| Intussusception type | Etiology | Coloscopy diagnosis | |

| Diagnosis of intussuscption | Etiological diagnosis | ||

| Enteric | Intestinal inflammatory disease | No | Intestinal inflammatory disease |

| Ileocolic | - (After appendectomy) | Yes | - |

| Ileocolic | Ileum B cell malignant lymphoma | Yes | Occupying lesion |

| Colocolonic | Colon lipoma | No | Occupying lesion |

| Colocolonic | Colon lipoma | Yes | Occupying lesion |

| Colocolonic | Ascending colon adenocarcinoma | No | Adenocarcinoma |

| Colocolonic | Ascending colon adenocarcinoma | No | Adenocarcinoma |

| Sigmoidorectal | Sigmoid colon villous and tubular adenoma | Yes | Villous and tubular adenoma |

Four intussusceptions in three patients, including two patients who had undergone gastrojejunostomy with an intestinal tube, and one patient with a retrograde idiopathic enteric intussusception, were simply reduced. One patient with a mobile cecum underwent appendectomy and cecum immobilization after primary reduction. Eighteen patients underwent segmental resection of the small bowel, 17 underwent a right hemicolectomy, one underwent a left hemicolectomy, and one patient with a sigmoidorectal intussusception underwent a segmental sigmoidectomy. One patient with multiple small and large intestinal adenomas underwent segmental resection of the small and large bowel. Of the 41 patients, 21 underwent resection after primary reduction (Table 1).

Of the 20 enteric intussusceptions, four of them (20%) underwent a simple reduction, nine (45%) had a segmental resection with primary reduction, four (20%) failed in reduction, and three (15%) had segmental resection without reduction.

Of the 15 ileocolic intussusceptions, nine (60%) were reduced successfully. Due to the reduction, five patients had limited resection with preservation of the antireflux ileocecal valve. Reduction failed in three patients (20%). Three of them (20%) had a right hemicolectomy without reduction.

Of the eight colocolic intussusceptions, three of them were reduced successfully before resection. The other five had resection without reduction. The sigmoidorectal intussusception was reduced and had a segmental sigmoidectomy.

There was no perioperative mortality and anastomosis leakage. Except for one patient with multiple small bowel adenomas recurrent 5 mo after surgery, none of them were recurrent within 6 months postoperatively.

Pathological examinations of the 44 intussusceptions showed that a tumor occupied 54.5% (24/44), with 27.3% (12/44) malignant, 25.0% (11/44) benign, and 2.3% (1/44) borderline. 9.1% (4/44) were nontumorous polyps. 4.5% (2/44) were due to intestinal inflammatory disease. Meckel’s diverticulum and mobile cecum accounted for 4.5% (2/44). Apart from three cases (four intussusceptions), who had already undergone a gastrojejunostomy, no organic lesion was found in four intussusceptions by pathology or exploration, one of which one was the only retrograde intussusception (see Tables 1 and 3).

| Enteric | Ileocolic | Colocolonic | Sigmoidorectal | Percentage | ||

| Tumor | Malignant | 6 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 27.3 (12/44) |

| Borderline | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.3 (1/44) | |

| Benign | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 25.0 (11/44) | |

| Nontumorous polyp | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 9.1 (4/44) | |

| Intestinal inflammatory disease | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 11.4 (5/44) | |

| Anatomy abnormality | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 4.5 (2/44) | |

| Iatrogenic | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 11.4 (5/44) | |

| Idiopathic | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 9.1 (4/44) | |

| Percentage | 45.5 (20/44) | 34.1 (15/44) | 18.2 (8/44) | 2.3 (1/44) | 100.0 (44/44) | |

Intussusception is the leading cause of intestinal obstruction in children and ranks second only to appendicitis as the most common cause of acute abdominal emergency in children. AI is distinct from pediatric intussusception in that it is rare, accounting for only 5% of all cases of intestinal obstructions, and about 90% of it is secondary. The exact mechanism is still unknown. However, it is believed that any lesion in the bowel wall or irritant within the lumen that alters normal peristaltic activity is able to initiate an invagination. Ingested food and subsequent peristaltic activity of the bowel produces an area of constriction above the stimulus and relaxation below, thus telescoping the lead point through the distal bowel lumen[134].

Similar to the results of Zubadi et al[1], enteric type intussusception is the most common type in our series. However, in the report of Goh et al[4] of 60 cases of AI, ileocolic (25%) and ileocecal-colic (13.3%) types were the most common. Their enteric type occupied 26.7%. Similar to our results, their colocolic and sigmoidorectal types were the least common types.

Most patients present with subacute (24.4%) or chronic (51.2%) symptoms; therefore the characteristic pediatric presentation triad of abdominal pain, palpable abdominal mass and bloody stool was only seen in 9.8% of cases. It is one of the reasons why preoperative diagnosis is difficult.

Ultrasound is apt to be masked by gas-filled loops of bowel, and most AIs present with intestinal obstruction[6]. The preoperative diagnosis accuracy (60.0%) of ultrasonography is not satisfying. However, the preoperative diagnosis accuracy of the 12 patients who had palpable abdominal mass was 91.7%, indicating that in cases of palpable abdominal mass, the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography would increase significantly.

Recently, with the signs of target or sausage, mesenteric fat and vessels, abdominal CT scan has been reported to be the most useful imaging technique, with a diagnostic accuracy is 58%-100%[3–578]. Recent studies have demonstrated the superiority of CT in revealing the site, level, and cause of intestinal obstructions and in demonstrating threatening signs of bowel nonviability[910]. As was shown in our study, the majority of AIs presented with partial or complete intestinal obstruction. Moreover, 90.5% (20/22) of AIs were diagnosed by CT in our series. One case of AI that was not diagnosed by CT, however, was correctly diagnosed as having an intestinal occupying lesion. In contrast to ultrasound, CT is not affected by the presence of gas in the bowel and will clearly demonstrate the intussusception, whether in the small bowel or in the colon. Additional valuable information, such as metastasis or lymphadenopathy, is readily obtained by CT and may point to an underlying pathology[5]. Therefore, we suggest that all patients presenting with an intestinal obstruction should have an abdominal CT scan as a regular diagnostic test.

Wang et al[3] considered that most lesions lead distally, can easily be seen by coloscopy, and intraoperative coloscopy might help to distinguish benign from malignant lesions before reduction of intussusceptions. Using the results of a coloscopy, limited surgical management by appendectomy, polypectomy or diverticulectomy might be performed in specific situations, resulting in an uncompromised bowel after reduction[3]. In our study, all lesions of the lead points of ileocolic, colocolic or sigmoidorectal intussusceptions were found in the seven patients who had a colonoscopy. Moreover, all the adenoma and adenocarcinomas were diagnosed pathologically through colonoscopy. However, some lesions, such as lymphoma and lipoma, which were not in the mucosa, were not diagnosed pathologically. Therefore, we think that the pathological diagnosis of most of the lead points of ileocolic, colocolic and sigmoidorectal intussusceptions, which locate in the mucosa, could be made by coloscopy. Perhaps some lesions, such as appendicitis and polyps, could be diagnosed by coloscopy to avoid undue surgery.

It is reported that 8%-20% of AIs are idiopathic and are more likely to occur in the small intestine[6]. In our series, there were four [9.1% (4/44)] patients whose etiologies were not found by surgical exploration and/or pathology. One of them occurred in the colon (see Tables 1 and 3). Three of them had intestinal necrosis with bleeding. Segments of intestine had to be resected. The only retrograde intussusception found in our patients was cured by simple reduction.

Most AIs have underlying pathological lesions; therefore, most authors agree that laparotomy is mandatory. However, whether or not the intussusception should be reduced before resection remains controversial. The theoretical objections to reductions are intraluminal seeding and venous dissemination of malignant cells, possible perforation during manipulation and increased risk of anastomotic complications in the face of edematous and inflamed bowel[1].

Although only 30% (6/20) of the etiologies of our enteric intussusceptions were malignant, borderline leiomyoma is potentially malignant. Therefore, reduction before resection would be more prudent. We suggest that if the underlying etiology and/or the lead point is suspected to be malignant, or if resected area required without reduction is not massive, an en bloc resection of the intussusception should be considered.

There were only three cases (37.5%) of colocolic intussusceptions caused by a malignant tumor-adenocarcinoma in our series, but most authors report malignant pathology presents in 69%-100%[34]. Only one case of ileocolic intussusception had a malignant organic lesion (terminal ileum B cell malignant lymphoma) in our series. Wang et al[3] reported 5/12 patients had malignant lesions in this type of intussusception. They think intraoperative colonoscopy might help to distinguish benign from malignant lesions before reduction. This technique can identify benign lesions of the ileum and be used to perform limited resection with preservation of the antireflux ileocecal valve. Moreover, appendectomy, polypectomy or diverticulectomy might be performed in specific situations to produce an uncompromised bowel after reduction, when definitively diagnosed by coloscopy[3]. Our coloscopies found all (7/7) of the lead point lesions and diagnosed all of the adenoma and adenocarcinomas of non-enteric intussusceptions. In our study, the lesions of appendicitis, benign tumors and polyps might have been diagnosed by coloscopy; organic lesion might have been excluded on the patient who had undergone appendectomy before exploration for intussusception. If coloscopy had been undertaken, unnecessary surgery could have been avoided. Therefore, we consider that in ileocolic, colocolic and sigmoidorectal intussusceptions, coloscopy is necessary, either preoperatively or intraoperatively.

The sigmoidorectal intussusception caused by villous and tubular adenoma of the sigmoid colon in our study was successfully reduced before partial resection of the sigmoid colon and the patient was spared a Miles operation. Zubaidi et al[1] considered that even if an intussusception of this type is secondary to a carcinoma, to avoid an abdominoperineal resection and a permanent colostomy, reduction should be performed first.

There were three patients in our study who underwent gastrojejunostomy and nasojejunal intubation for enteral nutrition and had efferent loop intussusceptions. All of them were misdiagnosed as gastroplegia initially. The tube had been intubated together with a nasogastric tube into the stomach. During the operation, before completion of the gastrojejunostomy, a candy ball enveloped with a pertured surgery glove finger end, which was tied on the tip of the tube, was put into the efferent loop, then the candy ball was drawn from the outside of the efferent loop more than 40 cm distally to the anastomosis. Gayer et al[5] and Erkan et al[6] also consider intestinal intubation in the etiology of intussusception. However, they did not illuminate the mechanism of it. It is well known that the mucosal and seromuscular layers of the intestine connect loosely with each other. We think that when the candy ball on the tip of the tube is drawn distally, because of friction, the proximal mucosa will be pushed, folded and prolapsed distally. If the muscularis of mucosa is injured, then the distally pushed mucosa will not be able to recover by itself. As a result, the mucosa could prolapse distally and protrude into the intestinal lumen like a ring shaped tumor, and then an intussusception could occur.

In conclusion, AI is an infrequent problem. Most AIs present with subacute and chronic symptoms have intestinal obstructions to various extents. CT is the most effective and accurate diagnostic technique. In the case of a palpable abdominal mass, ultrasonography is also helpful for diagnosis. Enteric intussusception should be reduced when the underlying etiology is suspected to be benign or the resection is massive without reduction. Most lead point lesions of the ileocolic, colocolic or sigmoidorectal intussusceptions can be found by coloscopy. For these types of intussusceptions, coloscopy might provide information allowing the avoidance of unnecessary surgery. Intestinal intubation is the main cause of iatrogenic intussusception and should be avoided.

Intussusception is uncommon in adults. It is estimated that only 5% of all intussusceptions occur in adults and approximately 5% of bowel obstructions in adults are the result of intussusception. Adult intussusception (AI) often presents with nonspecific symptoms. Preoperative diagnosis remains difficult. The extent of resection and whether the intussusception should be reduced remains controversial.

Recent researches are focused on accurate preoperative diagnosis and proper treatment of it.

According to their data, the authors found computed tomography (CT) is the most effective and accurate diagnostic technique. In case of a palpable abdominal mass, ultrasonography is also helpful for diagnosis. Enteric intussusception should be reduced when the underlying etiology is suspected to be benign or the resection is massive without reduction. Most lead point lesions of the ileocolic, colocolic or sigmoidorectal intussusceptions can be found by coloscopy. For these types of intussusception, coloscopy might provide information that allows avoidance of unnecessary surgery. Intestinal intubation is the main cause of iatrogenic intussusception and should be avoided. They also propose a hypothesis for the occurrence of this kind of intussusception.

The authors suggest that all patients presenting with an intestinal obstruction or the patients who are suspected intussusception, have an abdominal CT scan as a regular diagnostic test. In cases with a palpable abdominal mass, ultrasonography should be applied. If non-enteric intussusception is suspected, coloscopy might provide information allowing the avoidance of unnecessary surgery. Enteric intussusception should be reduced when the underlying etiology is suspected to be benign or the resection is massive without reduction. Intestinal intubation should be omitted unless very necessary or carried out very gently or with lubrication.

Intussusception: defined as the telescoping of a segment of the gastrointestinal tract into an adjacent one; enteric intussusception: an intussusception involved only jejunum or ileum is considered an enteric intussusception; ileocolic intussusception: an intussusception that involves the ileum and the colon is designated an ileocolic intussusception; colocolonic intussusception: an intussusception involving only the colon is considered a colocolonic intussusception; sigmoidorectal intussusception: involving the sigmoid colon and rectum; non-enteric intussusception: including ileocolic, colocolonic and sigmoidorectal intussusceptions. Acute symptoms: defined as < 4 d; Subacute symptoms: defined as 4-14 d. Chronic symptoms: defined as > 14 d. Antegrade intussusception: the proximal segment of the bowel telescoped into the lumen of the adjacent distal segment is defined as antegrade intussusception. Retrograde intussusception: the distal segment of the bowel telescoped into the lumen of the adjacent proximal segment is defined as retrograde intussusception.

The authors reviewed 41 cases of adult intussuception. The article is well written and worthy of publication.

| 1. | Zubaidi A, Al-Saif F, Silverman R. Adult intussusception: a retrospective review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1546-1551. |

| 2. | Chand M, Bradford L, Nash GF. Intussusception in colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2008;7:204-205. |

| 3. | Wang LT, Wu CC, Yu JC, Hsiao CW, Hsu CC, Jao SW. Clinical entity and treatment strategies for adult intussusceptions: 20 years’ experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1941-1949. |

| 4. | Goh BK, Quah HM, Chow PK, Tan KY, Tay KH, Eu KW, Ooi LL, Wong WK. Predictive factors of malignancy in adults with intussusception. World J Surg. 2006;30:1300-1304. |

| 5. | Gayer G, Zissin R, Apter S, Papa M, Hertz M. Pictorial review: adult intussusception--a CT diagnosis. Br J Radiol. 2002;75:185-190. |

| 6. | Erkan N, Haciyanli M, Yildirim M, Sayhan H, Vardar E, Polat AF. Intussusception in adults: an unusual and challenging condition for surgeons. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2005;20:452-456. |

| 7. | Barussaud M, Regenet N, Briennon X, de Kerviler B, Pessaux P, Kohneh-Sharhi N, Lehur PA, Hamy A, Leborgne J, le Neel JC. Clinical spectrum and surgical approach of adult intussusceptions: a multicentric study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:834-839. |

| 8. | Tan KY, Tan SM, Tan AG, Chen CY, Chng HC, Hoe MN. Adult intussusception: experience in Singapore. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:1044-1047. |

| 9. | Boudiaf M, Soyer P, Terem C, Pelage JP, Maissiat E, Rymer R. Ct evaluation of small bowel obstruction. Radiographics. 2001;21:613-624. |

| 10. | Beattie GC, Peters RT, Guy S, Mendelson RM. Computed tomography in the assessment of suspected large bowel obstruction. ANZ J Surg. 2007;77:160-165. |