Published online Jul 14, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3254

Revised: May 11, 2009

Accepted: May 18, 2009

Published online: July 14, 2009

AIM: To characterize thermal hypersensitivity in patients with constipation- and diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

METHODS: Thermal pain sensitivity was tested among patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS (D-IBS) and constipation-predominant IBS (C-IBS) compared to healthy subjects. A total of 42 patients (29 female and 13 male; mean age 27.0 ± 6.4 years) with D-IBS; 24 patients (16 female and eight male; mean age 32.5 ± 8.8 years) with C-IBS; and 52 control subjects (34 female and 18 male; mean age 27.3 ± 8.0 years) participated in the study. Thermal stimuli were delivered using a Medoc Thermal Sensory Analyzer with a 3 cm × 3 cm surface area. Heat pain threshold (HPTh) and heat pain tolerance (HPTo) were assessed on the left ventral forearm and left calf using an ascending method of limits. The Functional Bowel Disease Severity Index (FBDSI) was also obtained for all subjects.

RESULTS: Controls were less sensitive than C-IBS and D-IBS (both at P < 0.001) with no differences between C-IBS and D-IBS for HPTh and HPTo. Thermal hyperalgesia was present in both groups of IBS patients relative to controls, with IBS patients reporting significantly lower pain threshold and pain tolerance at both test sites. Cluster analysis revealed the presence of subgroups of IBS patients based on thermal hyperalgesia. One cluster (17% of the sample) showed a profile of heat pain sensitivity very similar to that of healthy controls; a second cluster (47% of the sample) showed moderate heat pain sensitivity; and a third cluster (36% of the sample) showed a very high degree of thermal hyperalgesia.

CONCLUSION: A subset of IBS patients had thermal hypersensitivity compared to controls, who reported significantly lower HPTh and HPTo. All IBS patients had a higher score on the FBDSI than controls. Interestingly, the subset of IBS patients with high thermal sensitivity (36%) had the highest FBDSI score compared to the other two groups of IBS patients.

- Citation: Zhou Q, Fillingim RB, Riley III JL, Verne GN. Thermal hypersensitivity in a subset of irritable bowel syndrome patients. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(26): 3254-3260

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i26/3254.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.3254

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is one of the most common gastrointestinal disorders encountered by gastroenterologists. Patients classically present with chronic abdominal pain associated with an alteration in bowel habits. Even though the pathophysiology of the IBS is unclear, visceral hypersensitivity is a common clinical marker of the disorder[12]. Visceral hypersensitivity may account for symptoms of abdominal pain, urgency, and bloating experienced by many patients with this disorder.

Although visceral hypersensitivity is considered a hallmark feature of IBS, conflicting evidence exists regarding somatic hypersensitivity in this patient population. Somatic pain conditions, such as fibromyalgia and migraine headaches show significant comorbidity with IBS, which suggests that somatic hypersensitivity characterizes at least a subpopulation of IBS patients[23]. Several investigators have found no evidence for heightened somatic pain sensitivity in IBS patients. For example, two studies reported that IBS patients showed lower sensitivity to painful electrocutaneous stimuli compared to healthy controls[45]. Also, others have reported similar cold pressor pain tolerance in IBS patients and controls[67]. In contrast, our recent studies using hot water immersion have shown widespread somatic hyperalgesia associated with IBS[289], and others using the cold pressor test have demonstrated somatic hypersensitivity in IBS patients compared with healthy controls[310].

These conflicting findings may result from differing somatic pain testing procedures. Alternatively, patient sampling may be a contributing factor, given that there may be subgroups of IBS patients who differ in their somatic sensitivity. For example, somatic hypersensitivity may be present only in a subset of patients based on IBS subtype [i.e. diarrhea-predominant IBS (D-IBS) vs constipation-predominant IBS (C-IBS)], symptom severity and/or psychological profile.

Previous studies have explored the correlates of visceral hypersensitivity among patients with IBS[11–16]. For example, depression is correlated with rectal pain thresholds only in patients who alternate between constipation and diarrhea. Others have reported no association of psychological factors with rectal sensitivity; however, hypersensitivity to rectal distention is associated with increased IBS symptom severity assessed by daily diary[11]. Similarly, other investigators have found that rectal pain sensitivity is correlated positively with clinical symptoms among IBS patients[12–14], while others have reported no such association[1516]. However, the association of somatic hypersensitivity with clinical symptoms in IBS has not been evaluated.

To further evaluate somatic hyperalgesia among patients with IBS, we evaluated thermal pain sensitivity among patients with D-IBS and C-IBS compared with healthy subjects. The aims of the present study were: (a) to compare the spatial distribution and magnitude of thermal hyperalgesia between D-IBS and C-IBS patients and controls; and (b) to compare the spatial distribution and magnitude of thermal hyperalgesia among IBS patients as a function of symptom severity.

A total of 42 patients (29 female and 13 male; mean age 27.0 ± 6.4 years) with D-IBS; 24 patients (16 female and eight male; mean age 32.5 ± 8.8 years) with C-IBS; and 52 control subjects (34 females and 18 male; mean age 27.3 ± 8.0 years) participated in the study. The demographics of the participating subjects are presented in Table 1. IBS subjects and healthy controls were recruited via advertisements posted at the University of Florida and the Ohio State University. The study was approved by the University of Florida, the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System, and the Ohio State University Institutional Review Boards. All subjects signed informed consent prior to the start of the study.

| D-IBS (n = 42) | C-IBS (n = 24) | Controls (n = 52) | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 27.0 ± 6.4 | 32.5 ± 8.8 | 27.3 ± 8.0 |

| Sex (female), n (%) | 29 (69) | 16 (67) | 34 (64) |

| FBDSI | 62.8 (23.2) | 68.4 (25.3) | 2.1 (4.9) |

| Self-reported race/ethnicity n (%) | |||

| White | 33 (79) | 15 (63) | 43 (83) |

| Black | 3 (7) | 6 (25) | 3 (6) |

| Hispanic | 3 (7) | 1 (4) | 3 (6) |

| Asian | 3 (7) | 2 (8) | 3 (6) |

None of the control subjects had any evidence of acute or chronic somatic/abdominal pain or IBS based on a questionnaire and complete physical examination by an experienced gastroenterologist. Also, controls were free of any systemic medical disease or psychological conditions that could affect sensory responses. All IBS subjects had symptoms for at least 5 years. The diagnosis of IBS was made by the same gastroenterologist who examined patients based on the ROME III criteria and exclusion of organic disease[17]. All subjects with IBS were examined for fibromyalgia (FM) using the 1990 American College of Rheumatology criteria for FM[18]. None of the patients were diagnosed as having FM. None of the IBS or control subjects were taking analgesics, serotonin uptake inhibitors, serotonin antagonists, or tricyclic antidepressants for a period of at least 3 wk prior to the study.

All subjects underwent experimental psychophysical testing during a single session. All sessions were conducted between 9 AM and 6 PM to control for circadian rhythm effects. Subjects were instructed to refrain from the use of any analgesic medication for 48 h and from caffeine for 4 h before their sessions. Prior to each session, participants received a reminder concerning the restrictions on analgesic medication and caffeine use.

Female subjects participated during the follicular phase of their cycles (i.e. 4-9 d post onset of menses). This cycle phase was chosen because it is characterized generally by the least sensitivity to pain and by minimal menstrual cycle related symptoms[19]. The menstrual cycle has been reported to alter pain perception in women, and IBS symptoms have also been reported to fluctuate across the menstrual cycle[20]. In addition, the follicular phase was chosen because some female subjects would have been using oral contraceptives (OCs), and the follicular phase is the cycle phase during which women who use OCs and normal cycling women are the most similar in their responses to experimental pain[21].

Multiple psychological factors have been related to pain responses in a number of studies, and these factors may mediate partially group differences in pain sensitivity. Therefore, all participants completed psychological questionnaires that assessed coping style, anxiety, depression, and hyper-vigilance prior to the first experimental session. In addition, a measure of current affective state was administered prior to each experimental session. These measures were used as control variables (as further described in the data analysis section) to determine whether group differences in pain sensitivity remain significant after controlling for the influence of psychological variables.

The Coping Strategies Questionnaire (CSQ) consists of 44 items that are related to how individuals cope with pain[22]. It yields seven subscales based on the pain coping strategies: diverting attention, catastrophizing, praying and hoping, ignoring pain sensations, reinterpreting pain sensations, increasing behavioral activity, and coping self-statements. The CSQ also provides measures of subjects’ perceived ability to control and decrease pain. It has been used widely with various pain populations, and has been modified for use with healthy pain-free subjects, by having individuals respond to the instrument based on how they cope typically with day-to-day aches and pains[23]. Responses on the CSQ have previously been related to experimental pain responses[24], as well as clinical pain, including IBS[25–27]. We have used this scale in previous psychophysical and clinical research[28–30].

The Kohn reactivity scale consists of 24 items that assess an individual’s level of reactivity or central nervous system arousability. It has been used recently as a measure of the construct of hypervigilance[31]. This measure has been shown to correlate negatively with pain tolerance[3132] and has been reported to have adequate internal consistency, ranging from an α value of 0.73 to 0.83[33].

The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAXI) consists of 20 items that assess dispositional (i.e. trait) anxiety[34]. This is a well-validated and widely used instrument for assessing general anxiety.

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a widely used, 21-item, self-report measure that assesses common cognitive, affective and vegetative symptoms of depression. Research that has evaluated the psychometric properties of the BDI has suggested that it shows excellent reliability and validity as an index of depression[35]. Since chronic pain patients often endorse somatic symptoms assessed by the BDI, which may artificially inflate their scores[36], the BDI has been separated into a 13-item cognitive affective subscale and an eight-item somatic-performance subscale[37].

The Profile of Mood States-bipolar Form (POMS-BI) consists of 72 mood-related items, and subjects indicate the extent to which each item describes their current mood[38]. This questionnaire assesses positive and negative affective dimensions. The POMS-BI has been well validated with other mood measures and is sensitive to subtle differences in affective state. We have used this measure in previous psychophysical studies[28]. This mood measure was administered to determine the current affective state at the beginning of each sensory testing session.

Functional Bowel Disorder Severity Index (FBDSI) comprises three variables: current pain (by visual analog scale), diagnosis of chronic abdominal pain, and number of physician visits in the past 6 mo[39]. The FBDSI is sufficiently sensitive to distinguish among the different groups, from healthy controls, through non-IBS patients, to patients with IBS only and,finally, IBS patients with concomitant FM. Severity is rated as none (0 points, controls), mild (1-36 points, non-IBS patients), moderate (37-110 points, IBS patients), and severe (> 110 points, IBS and FM). All IBS patients that participated in the study were characterized with this index.

Thermal stimuli were delivered using a computer-controlled Medoc Thermal Sensory Analyzer (TSA-2001; Ramat Yishai, Israel). This is peltier-element-based stimulator with a 3 cm × 3 cm surface area. Temperature levels were monitored by a contactor-contained thermistor, and returned to a preset baseline of 32°C by active cooling at a rate of 10°C/s. Heat pain threshold (HPTh) and heat pain tolerance (HPTo) were assessed on the left ventral forearm and left calf using an ascending method of limits. The cutoff temperature (to avoid tissue damage) for all trials was 52°C. Subjects were assigned randomly within each group (controls, C-IBS, D-IBS) to receive thermal nociceptive stimulation to the left ventral forearm versus the left calf in a random order that was counterbalanced across all groups.

From a baseline of 32°C, probe temperature increased at a rate of 0.5°C/s until the subject responded by pressing a button on a handheld device. This slow rate of rise preferentially activates C-fibers and diminishes artifacts associated with reaction time.

For HPTh, subjects were informed via digitally recorded instructions to press the button when the sensation first became painful. Four trials of HPTh were performed at each site (ventral forearm and calf). The average of the four trials at each site was computed for HPTh. The position of the thermode was altered slightly between trials in order to avoid either sensitization or habituation of cutaneous receptors. In addition, interstimulus intervals of at least 30 s were maintained between successive stimuli. Four trials of HPTh were presented followed by a 15-min rest period, and then four trials of HPTo were performed.

For HPTo, subjects were instructed to press the button when the sensation was no longer tolerable. Four trials of HPTo were performed at each site (ventral forearm and calf). The average of the four trials at each site was computed for HPTo. The position of the thermode was altered slightly between trials in order to avoid either sensitization or habituation of cutaneous receptors. In addition, interstimulus intervals of at least 30 s were maintained between successive stimuli.

The primary analyses involved one between- and two within-subject variables, and consequently, the repeated measures command within the General Linear model module of SPSS was used. In the first primary analysis, differences between controls and D-IBS and C-IBS patients for HPTh and HPTo at the forearm and calf were tested. In the second primary analysis, associations between IBS symptom severity and HPTh and HPTo at the forearm and calf were tested. A series of one-way ANOVAs were used to test for group differences in psychological inventories. As a result of the number of statistical tests performed, a Bonferroni correction was used to maintain family-wise type 1 error rate at P < 0.05.

A total of 118 participants were studied, which included 42 patients (29 female and 13 males; mean age 27.0 ± 6.4 years) with D-IBS; 24 patients (16 female and eight male; mean age 32.5 ± 8.8 years) with C-IBS; and 52 control subjects (34 female and 18 males; mean age 27.3 ± 8.0 years) (Table 1). There was no difference in age or sex between the groups (controls, D-IBS and C-IBS). FBDSI score was higher in the D-IBS (62.8 ± 23.2) and C-IBS (68.4 ± 25.3) patients than the controls (2.1 ± 4.9), but did not differ between the patient groups.

HPTh and HPTo (mean ± SD) at both sites for C-IBS, D-IBS, and controls are presented in Table 2. We found significant effects for site, pain measure, and group (all at P < 0.001). Pair-wise comparisons supported the hypothesis that controls were less sensitive than C-IBS and D-IBS patients (both at P < 0.001), with no differences between C-IBS and D-IBS. Two-way interactions for pain measure × group (P = 0.002) and site × pain measure (P < 0.001) were also significant. Pair-wise comparisons revealed that controls had higher HPTh and HPTo than C-IBS and D-IBS (both at P < 0.001) on the forearm and the calf. There was no difference in HPTh or HPTo between C-IBS and D-IBS patients.

| Groups (n) | Threshold (HPTh) | Tolerance (HPTo) | ||

| Forearm | Calf | Forearm | Calf | |

| Controls (n = 52) | 43.2 ± 1.8 | 45.1 ± 1.7 | 48.0 ± 1.8 | 48.1 ± 1.4 |

| Diarrhea (n = 42) | 39.1 ± 3.3 | 41.1 ± 4.0 | 44.7 ± 3.8 | 44.9 ± 2.1 |

| Constipation (n = 24) | 39.6 ± 3.3 | 41.3 ± 3.5 | 45.0 ± 3.7 | 46.0 ± 3.1 |

| IBS symptom groups | ||||

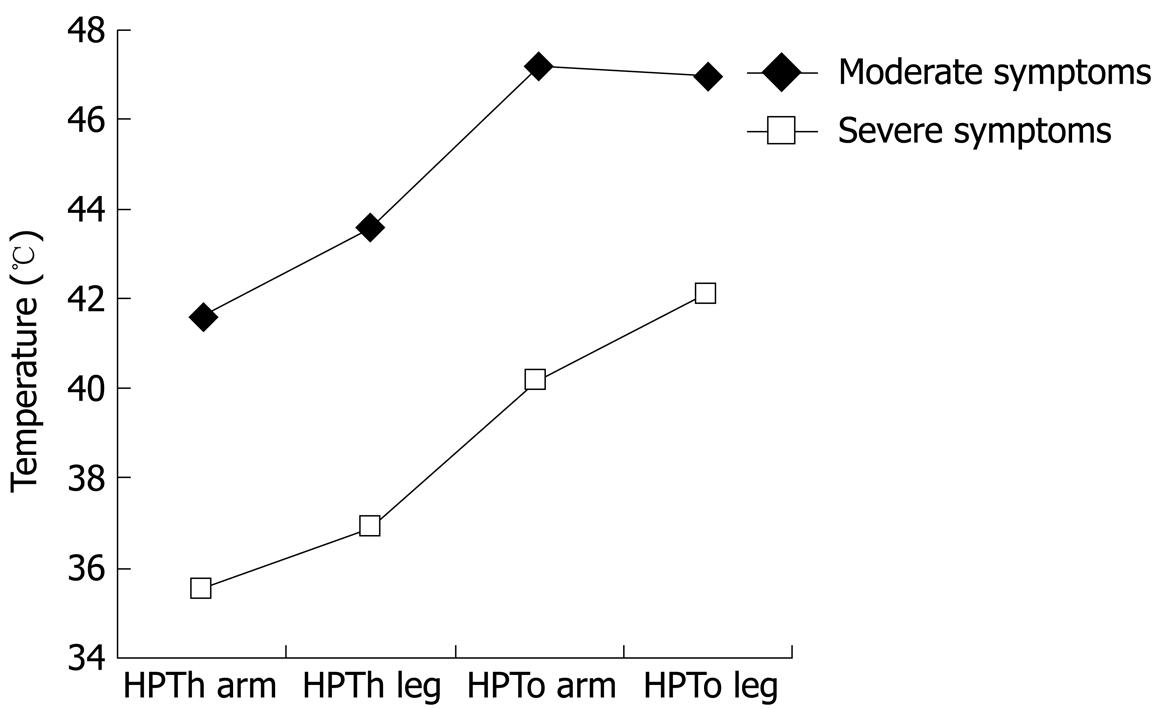

| Moderate symptoms (n = 42) | 41.6 ± 1.7 | 43.6 ± 1.9 | 47.2 ± 1.6 | 47.0 ± 1.3 |

| Severe symptoms (n = 24) | 35.6 ± 1.5 | 36.9 ± 1.6 | 40.2 ± 2.1 | 42.1 ± 1.6 |

A group effect emerged for Kohn scores (P = 004), with C-IBS (78.8 ± 9.9) having higher scores than D-IBS (70.8 ± 10.8) and controls (70.1 ± 11.1) (collapsed across groups, 72.1 ± 11.2). There were no differences in the BDI (3.4 ± 3.7), STAXI (28.0 ± 4.8), POMS positive (53.2 ± 15.7), POMS negative (29.8 ± 16.3) or any of the subscales of the CSQ (distracting attention, 10.0 ± 6.1; cognitive self-statements, 13.3 ± 5.3; ignoring pain sensations, 11.0 ± 6.1; praying and hoping, 5.4 ± 4.9; reinterpreting pain sensations, 4.9 ± 4.8; catastrophizing, 5.9 ± 6.1).

We found significant effects for site, pain measure, and symptom severity (all at P < 0.001). The site by symptom severity interaction was not significant; however, the 3-way interaction (site × pain × symptoms) was significant (P < 0.01). To interpret this interaction involving an internal level variable (IBS symptom severity) and two nominal variables, we examined scatter plots for HPTh and HPTo at the leg and arm by FBDSI scores. The results suggest a naturally occurring gap between scores of 72 and 82 that was associated with pain sensitivity; therefore, two groups were formed based on FBDSI scores, with a cutoff at 80. Demographic variables for the two symptom severity groups are presented in Table 3. HPTh and HPTo at both sites for the two IBS symptom severity groups are presented in Table 2 and Figure 1. The IBS symptom subgroups did not differ for Kohn, BDI, STAXI, POMS, or CSQ scores.

| Moderate sensitivity (n = 42) | High sensitivity (n = 24) | |

| Age (SD) | 28.7 (7.0) | 29.1 (7.3) |

| Sex (female) n (%) | 30 (71) | 15 (63) |

| FBDSI | 49.3 (9.1) | 96.4 (8.7) |

| Range 38-72 | Range 82-110 | |

| Diarrhea subtype n (%) | 25 (60) | 17 (41) |

| Constipation subtype n (%) | 17 (40) | 7 (29) |

| Self-reported race/ethnicity n (%) | ||

| White | 30 (71) | 18 (37) |

| Black | 9 (21) | 0 (0) |

| Hispanic | 1 (2) | 3 (75) |

| Asian | 2 (5) | 3 (60) |

Overall, our findings indicate thermal hyperalgesia for IBS-C and IBC-D patients relative to controls, with IBS patients reporting significantly lower pain threshold and pain tolerance at both test sites. These findings add further support to the notion that IBS patients show somatic hyperalgesia. A unique finding of our study is that we detected a strong relationship between heat pain measures and FBDSI scores. IBS patients with high FBDSI scores had the highest thermal pain sensitivity compared to IBS patients with low to moderate FBDSI scores.

In contrast to our current findings, several previous studies have indicated lack of somatic hyperalgesia among IBS patients relative to controls[67], with some studies actually showing higher pain threshold among IBS patients relative to controls[45]. One possible explanation for this is differences in the painful stimulus, as previous studies have used electrical stimuli, mechanical pressure, and cold immersion, but none has used contact heat. Also, Chang and colleagues[40] have reported that female IBS patients showed significantly higher pressure pain threshold than female controls in response to a randomly administered series of fixed stimuli, but no group differences emerged for threshold assessed using ascending stimuli. Randomly administered stimuli are thought to reduce response bias, which is likely driven by psychological factors such as hypervigilance. Since we used ascending stimuli in the present study, it is possible that response bias contributed to our results. However, this seems unlikely given the lack of correlations between psychological factors, including anxiety and hypervigilance, and heat pain responses. Differences in the nature of the patient population may present another explanation for the differences between our findings and those of previous studies. Most prior investigations[4–7] recruited IBS patients from clinical settings, typically in tertiary care centers, whereas our IBS sample was recruited from the community, using print and postal advertisements. This community-based recruitment approach yielded a psychologically healthy IBS population, which was similar to the controls for most psychological measures. Moreover, most previous studies have included a female-only population, while we included women and men in both the IBS and control samples. Thus, differences in the experimental pain stimulus and patient population may have contributed to the differing pattern of results.

Consistent with the present findings, other investigators have reported somatic hyperalgesia in IBS patients, using cold pain[310], and we have shown similar results with heat immersion[28]. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of an association between somatic pain sensitivity and clinical symptoms among patients with IBS. Wilder-Smith and colleagues[10] have reported a strong association between somatic and visceral hypersensitivity. However, there is mixed evidence regarding the association between visceral hypersensitivity and clinical symptoms in IBS[1113151641]. In our study, the association of somatic hyperalgesia with FBDSI score suggests that central mechanisms contribute to the severity of patients’ clinical symptoms. This has potentially important treatment implications, as one might speculate that patients exhibiting somatic hypersensitivity may benefit from treatments that alter central processes, rather than those that are restricted to peripheral targets.

Several limitations of this study should be mentioned. First, somatic pain testing was limited to HPTh and HPTo and did not include other stimuli. Thus, it is not possible to determine whether these findings are specific to heat pain. Second, we did not assess sensitivity to visceral stimuli, and it would be interesting to know whether heat pain sensitivity is associated with visceral sensitivity. However, given our relatively large sample size, visceral testing was not feasible. Finally, based on the current design, we were unable to identify the mechanisms that underlie heat hyperalgesia and its association with clinical symptoms. Despite these limitations, the relatively large sample size, the use of heat pain measures designed to activate C-fibers, and the strong association between heat pain sensitivity and IBS symptom severity represent unique and valuable features of our study.

Our study indicates somatic hypersensitivity for both groups of IBS patients relative to controls, with IBS patients reporting significantly lower thermal pain threshold and tolerance. Moreover, somatic pain sensitivity was associated with IBS symptoms, such that patients with high FBDSI scores showed significantly greater pain sensitivity compared to those with low to moderate FBDSI scores. Further studies are warranted to evaluate somatic hypersensitivity as a predictor of clinical symptoms in IBS.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is one of the most common gastrointestinal disorders encountered by gastroenterologists. Patients present classically with chronic abdominal pain associated with an alteration in bowel habits. Even though the pathophysiology of IBS is unclear, visceral hypersensitivity is a common clinical marker of the disorder. Visceral hypersensitivity may account for symptoms of abdominal pain, urgency, and bloating experienced by many patients with this disorder.

Although visceral hypersensitivity is considered a hallmark feature of IBS, conflicting evidence exists regarding somatic hypersensitivity in this patient population. Somatic pain conditions, such as fibromyalgia and migraine headaches show significant comorbidity with IBS, which suggests that somatic hypersensitivity characterizes at least a subpopulation of IBS patients. Several recent studies using hot water immersion have shown widespread somatic hyperalgesia associated with IBS, and others using the cold pressor test have demonstrated somatic hypersensitivity in IBS patients compared with healthy controls.

Overall, the findings indicate thermal hyperalgesia for constipation- and diarrhea-dependent IBS relative to controls, with IBS patients reporting significantly lower pain threshold and tolerance at both test sites. These findings add further support to the notion that IBS patients show somatic hyperalgesia. A unique finding of this study is that the authors detected a strong relationship between heat pain measures and Functional Bowel Disease Severity Index (FBDSI) scores. IBS patients with high FBDSI scores had the highest thermal pain sensitivity compared to those IBS patients with low to moderate FBDSI scores.

This study suggests that a subset of IBS patients has evidence of somatic hypersensitivity that may relate to extra-intestinal symptoms.

This is an elegant study that evaluated systematically thermal hypersensitivity in a large number of IBS patients. The results are novel and interesting and may lead to new therapy in a subset of IBS patients with somatic hypersensitivity.

| 1. | Naliboff BD, Munakata J, Fullerton S, Gracely RH, Kodner A, Harraf F, Mayer EA. Evidence for two distinct perceptual alterations in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 1997;41:505-512. |

| 2. | Verne GN, Robinson ME, Price DD. Hypersensitivity to visceral and cutaneous pain in the irritable bowel syndrome. Pain. 2001;93:7-14. |

| 3. | Bouin M, Meunier P, Riberdy-Poitras M, Poitras P. Pain hypersensitivity in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders: a gastrointestinal-specific defect or a general systemic condition? Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:2542-2548. |

| 4. | Accarino AM, Azpiroz F, Malagelada JR. Selective dysfunction of mechanosensitive intestinal afferents in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:636-643. |

| 5. | Cook IJ, van Eeden A, Collins SM. Patients with irritable bowel syndrome have greater pain tolerance than normal subjects. Gastroenterology. 1987;93:727-733. |

| 6. | Whitehead WE, Holtkotter B, Enck P, Hoelzl R, Holmes KD, Anthony J, Shabsin HS, Schuster MM. Tolerance for rectosigmoid distention in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:1187-1192. |

| 7. | Zighelboim J, Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR. Visceral perception in irritable bowel syndrome. Rectal and gastric responses to distension and serotonin type 3 antagonism. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:819-827. |

| 8. | Verne GN, Himes NC, Robinson ME, Gopinath KS, Briggs RW, Crosson B, Price DD. Central representation of visceral and cutaneous hypersensitivity in the irritable bowel syndrome. Pain. 2003;103:99-110. |

| 9. | Verne GN, Price DD. Irritable bowel syndrome as a common precipitant of central sensitization. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2002;4:322-328. |

| 10. | Wilder-Smith CH, Robert-Yap J. Abnormal endogenous pain modulation and somatic and visceral hypersensitivity in female patients with irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3699-3704. |

| 11. | van der Veek PP, Van Rood YR, Masclee AA. Symptom severity but not psychopathology predicts visceral hypersensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:321-328. |

| 12. | Kanazawa M, Palsson OS, Thiwan SI, Turner MJ, van Tilburg MA, Gangarosa LM, Chitkara DK, Fukudo S, Drossman DA, Whitehead WE. Contributions of pain sensitivity and colonic motility to IBS symptom severity and predominant bowel habits. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2550-2561. |

| 13. | Posserud I, Syrous A, Lindström L, Tack J, Abrahamsson H, Simrén M. Altered rectal perception in irritable bowel syndrome is associated with symptom severity. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1113-1123. |

| 14. | Awad RA, Camacho S, Martín J, Ríos N. Rectal sensation, pelvic floor function and symptom severity in Hispanic population with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Colorectal Dis. 2006;8:488-493. |

| 15. | Castilloux J, Noble A, Faure C. Is visceral hypersensitivity correlated with symptom severity in children with functional gastrointestinal disorders? J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008;46:272-278. |

| 16. | Sabate JM, Veyrac M, Mion F, Siproudhis L, Ducrotte P, Zerbib F, Grimaud JC, Dapoigny M, Dyard F, Coffin B. Relationship between rectal sensitivity, symptoms intensity and quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:484-490. |

| 17. | Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1480-1491. |

| 18. | Geel SE. The fibromyalgia syndrome: musculoskeletal pathophysiology. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1994;23:347-353. |

| 19. | Riley JL 3rd, Robinson ME, Wise EA, Price DD. A meta-analytic review of pain perception across the menstrual cycle. Pain. 1999;81:225-235. |

| 20. | Heitkemper MM, Jarrett M. Pattern of gastrointestinal and somatic symptoms across the menstrual cycle. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:505-513. |

| 21. | Fillingim RB, Ness TJ. Sex-related hormonal influences on pain and analgesic responses. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2000;24:485-501. |

| 22. | Rosenstiel AK, Keefe FJ. The use of coping strategies in chronic low back pain patients: relationship to patient characteristics and current adjustment. Pain. 1983;17:33-44. |

| 23. | Lefebvre JC, Lester N, Keefe FJ. Pain in young adults. II: The use and perceived effectiveness of pain-coping strategies. Clin J Pain. 1995;11:36-44. |

| 24. | Geisser ME, Robinson ME, Pickren WE. Differences in cognitive coping strategies among pain sensitive and pain tolerant individuals on the cold pressor test. Beh Ther. 1992;23:31-41. |

| 25. | Keefe FJ, Caldwell DS, Queen KT, Gil KM, Martinez S, Crisson JE, Ogden W, Nunley J. Pain coping strategies in osteoarthritis patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1987;55:208-212. |

| 26. | Keefe FJ, Dolan E. Pain behavior and pain coping strategies in low back pain and myofascial pain dysfunction syndrome patients. Pain. 1986;24:49-56. |

| 27. | Scarinci IC, McDonald-Haile J, Bradley LA, Richter JE. Altered pain perception and psychosocial features among women with gastrointestinal disorders and history of abuse: a preliminary model. Am J Med. 1994;97:108-118. |

| 28. | Fillingim RB, Keefe FJ, Light KC, Booker DK, Maixner W. The influence of gender and psychological factors on pain perception. J Gender Cult Health. 1996;1:21-36. |

| 29. | Fillingim RB, Maixner W, Kincaid S, Sigurdsson A, Harris MB. Pain sensitivity in patients with temporomandibular disorders: relationship to clinical and psychosocial factors. Clin J Pain. 1996;12:260-269. |

| 30. | Riley JL 3rd, Robinson ME, Geisser ME. Empirical subgroups of the Coping Strategies Questionnaire-Revised: a multisample study. Clin J Pain. 1999;15:111-116. |

| 31. | McDermid AJ, Rollman GB, McCain GA. Generalized hypervigilance in fibromyalgia: evidence of perceptual amplification. Pain. 1996;66:133-144. |

| 32. | Dubreuil DL, Kohn PM. Reactivity and response to pain. Pers Indiv Diff. 1986;7:907-909. |

| 33. | Kohn PM. Sensation seeking, augmenting-reducing, and strength of the nervous system. Motivation, Emotion, and Personality. Amsterdam: Elsevier 1985; 167-173. |

| 34. | Spielberger CD, Gorusch RL, Lushene R, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y1). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press 1983; . |

| 35. | Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 1988;8:77-100. |

| 36. | Novy DM, Nelson DV, Berry LA, Averill PM. What does the Beck Depression Inventory measure in chronic pain?: a reappraisal. Pain. 1995;61:261-270. |

| 37. | Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck depression inventory manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation 1987; . |

| 38. | Lorr M, McNair DM. Profile of Mood States: Bipolar Form (POMS-BI). San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Service 1988; . |

| 39. | Sperber AD, Carmel S, Atzmon Y, Weisberg I, Shalit Y, Neumann L, Fich A, Friger M, Buskila D. Use of the Functional Bowel Disorder Severity Index (FBDSI) in a study of patients with the irritable bowel syndrome and fibromyalgia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:995-998. |

| 40. | Chang L, Mayer EA, Johnson T, FitzGerald LZ, Naliboff B. Differences in somatic perception in female patients with irritable bowel syndrome with and without fibromyalgia. Pain. 2000;84:297-307. |

| 41. | Kuiken SD, Lindeboom R, Tytgat GN, Boeckxstaens GE. Relationship between symptoms and hypersensitivity to rectal distension in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:157-164. |