Published online May 14, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2283

Revised: April 3, 2009

Accepted: April 10, 2009

Published online: May 14, 2009

Iatrogenic bile-duct injury post-laparoscopic cholecystectomy remains a major serious complication with unpredictable long-term results. We present a patient who underwent laparoscopic cholecystectomy for gallstones, in which the biliary injury was recognized intraoperatively. The surgical procedure was converted to an open one. The first surgeon repaired the injury over a T-tube without recognizing the anatomy and type of the biliary lesion, which led to an unusual biliary mal-repair. Immediately postoperatively, the abdominal drain brought a large amount of bile. A T-tube cholangiogram was performed. Despite the contrast medium leaking through the abdominal drain, the mal-repair was unrecognized. The patient was referred to our hospital for biliary leak. Ultrasound and cholangiography was repeated, which showed an unanatomical repair (right to left hepatic duct anastomosis over the T-tube), with evidence of contrast medium coming out through the abdominal drain. Eventually the patient was subjected to a definitive surgical treatment. The biliary continuity was re-established by a Roux-en-Y hepatico-jejunostomy, over transanastomotic external biliary stents. The patient is now doing well 4 years after the second surgical procedure. In reviewing the literature, we found a similar type of injury but we did not find a similar surgical mal-repair. We propose an algorithm for the treatment of early and late biliary injuries.

- Citation: Aldumour A, Aseni P, Alkofahi M, Lamperti L, Aldumour E, Girotti P, Carlis LGD. Repair of a mal-repaired biliary injury: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(18): 2283-2286

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i18/2283.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.2283

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has emerged as a gold standard of cholecystectomy and is the commonest laparoscopic surgical procedure performed by many surgeons worldwide. Unclear anatomy of the biliary tract and acute cholecystitis are associated with an elevated risk of bile duct injuries. These are serious surgical complications and are sometimes unrecognized during the procedure. A clear interpretation of the biliary anatomy as well as a good surgical experience are prerequisites for a definitive surgical repair. Primary surgical repair and further misinterpretation of the biliary anatomy with consequent mal-repair of the biliary tract injury are very unusual conditions. We present here a case of biliary tract injury that was recognized during LC but that was submitted to a mal-repair surgical procedure causing difficult problems of correct interpretation and management for the definitive surgical repair.

A 45-year-old woman was admitted to the referring hospital with symptomatic gallbladder stones for elective LC. She had not undergone any previous operations. Cholecystectomy was reported to be difficult by the operating surgeon. He reported that she had acute cholecystitis, and the biliary anatomy was not clear. During the operation he recognized that he caused a biliary injury, and for this reason he decided to convert the intervention to open surgery. He completed the cholecystectomy, and performed a repair of the biliary injury over a T-tube, according to his interpretation of the injury. He did not perform a cholangiogram before the repair, but the post-repair intraoperative cholangiogram was interpreted as a good repair. An infra-hepatic drain was inserted. During the first postoperative day, the abdominal drain brought out 500 mL of bile and the T-tube drained 100 mL of a similar fluid. On the following days, the abdominal drain brought 800-1000 mL of bile daily and the T-tube brought 40-60 mL daily. During the next 2 wk, the output through the drains did not decrease, and the treating surgeon asked to transfer the patient to our hospital, with a diagnosis of biliary fistula. The referring surgeon had an average experience in laparoscopic surgery. Past medical history revealed a non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus on oral medication.

In our hospital, the patient appeared pale, mildly dehydrated, not jaundiced and with normal vital signs. She was in the average weight range. The abdominal examination revealed a right sub-costal scar, two scars from the trocars, and two drains (an abdominal drain and the other was a T-tube) that both contained bile. She did not look septic.

The laboratory results showed: hemoglobin 10 g/dL; white blood cell count 11 300/mm³; K+ 3.2 meq/L; Na+ 132 meq/L. Liver enzymes and bilirubin were within the normal range.

Abdominal US showed normal liver size and echogenicity, without intra-hepatic biliary dilatation, a small sub-hepatic collection, and sub-hepatic multiple clips. The distal part of the biliary tree was not identified.

A T-tube cholangiogram (Figure 1) was done in our hospital, which showed a grade IV Bismuth injury, with the T-tube limbs within the left and right hepatic ducts. The biliary contrast medium appeared immediately through the abdominal drain, and the distal part of the biliary tree was not shown. These findings (mal-placed T-tube and fistula) suggested a plan for the definitive biliary surgical repair. We did not perform magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC), because the patient already had a T-tube, and also she had a sub-hepatic collection.

Informed consent was obtained from the patient and her family. She was given a prophylactic third-generation cephalosporin, which was continued for 24 h postoperatively. She was shifted to insulin therapy from the day she was admitted to our hospital, which was continued until she returned to her normal diet, on postoperative day 7. The intraoperative finding was a Bismuth grade IV injury that was repaired by right and left hepatic duct end-to-end anastomosis over a T-tube, performed by the referring surgeon. During exploration, we found an absence of the biliary confluence and the common hepatic duct, which may have indicated a misinterpretation by the first surgeon of the common hepatic duct as the cystic duct, therefore, he excised this region altogether with the gallbladder. Multiple clips on the distal biliary tree (common bile duct) were found. We also noted a bile leak from the posterior wall of the anastomosis that was performed previously over the T-tube. The T-tube was removed and a Roux-en-Y hepatico-jejunostomy over two trans-anastomotic stents was then performed (Figure 2). The patient had a good postoperative recovery without complications. The trans-stents’ cholangiogram performed on postoperative day 10 showed patent anastomosis without leakage. The stents were closed and the patient was discharged. The tubes were removed after 2 mo. The patient was followed up by clinical examination, liver enzymes and abdominal ultrasound (US), every 3 mo for the first year, every 6 mo for the second year, and then every year thereafter. In her final follow-up visit in August 2008, she was in good condition, 4 years after our surgical repair. She did not have any wound complications, neither in the early nor in the late postoperative period.

Misinterpretation of biliary anatomy was the main cause of biliary mal-repair. The hard task was to understand this mal-repair carried out by the referring surgeon, and then to perform a definitive biliary repair. The only possible explanation was that the referring surgeon misinterpreted the left hepatic duct as the common bile duct. This was very hard to recognize from the first radiological study, performed in the referring hospital, in which the contrast medium spilled out into the abdominal drain, and it was interpreted incorrectly as the common bile duct. As a result of the poor quality of this radiological study, we performed another T-tube cholangiogram and discussed the case with our radiologist, who confirmed our suspicion of the mal-repair. Although this kind of injury is well known (Bismuth type IV), we could not find a similar case of mal-repair in the English literature.

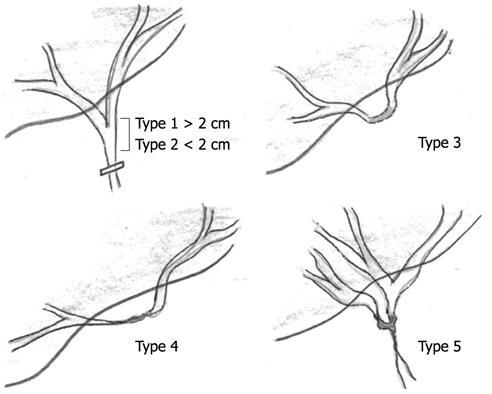

The incidence of biliary tract injury ranges from 0.2% to 0.8% worldwide, and even an experienced surgeon can cause such injury[1–5]. There is more than one classification for biliary injury, but the most widely used for surgical purposes are the Bismuth and Strasberg classifications (the later includes the former).

Our patient presented with grade IV Bismuth or Strasberg E IV biliary injury, which required surgical treatment. Figures 3 and 4 show drafts for both Bismuth and Strasberg classifications[467].

The referring surgeon tried to repair the injury immediately during the first operation. The identification of injury during surgery is reported to be between 15% and 50% of cases. Although primary repair is possible, and can be done laparoscopically, it should only be performed by an experienced surgeon. If this is not the case, drainage and referral to an experienced surgeon is the rule[238–10]. Poor identification of the anatomical features of the hepatic triangle represents the commonest cause of injury[3]. Bismuth noted that the level of the stricture found during repair was one level higher than the level of injury identified during the first operation[7]. During the re-operation for failed repair, the level of stricture has been reported to be even higher[11].

In our case, we re-established the biliary continuity by a Roux-en-Y hepatico-jejunostomy, after trimming the previous biliary anastomosis, over two stents inserted into the right and left hepatic ducts. A postoperative tube cholangiogram is shown in Figure 4. Different methods of repair have been reported by different surgical teams[5712]. Percutaneous and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) interventions can both be used in the management of biliary injuries, but under different conditions than ours[13]. We recommend, in cases that present with suspected stricture, to start with MRCP as the procedure of choice to identify the anatomy and the type of injury. In our specific case, the patient already had a drain in her biliary system, and she also had a biliary leak, therefore, it was appropriate to use these drains for delineating the biliary anatomy by a tube cholangiogram.

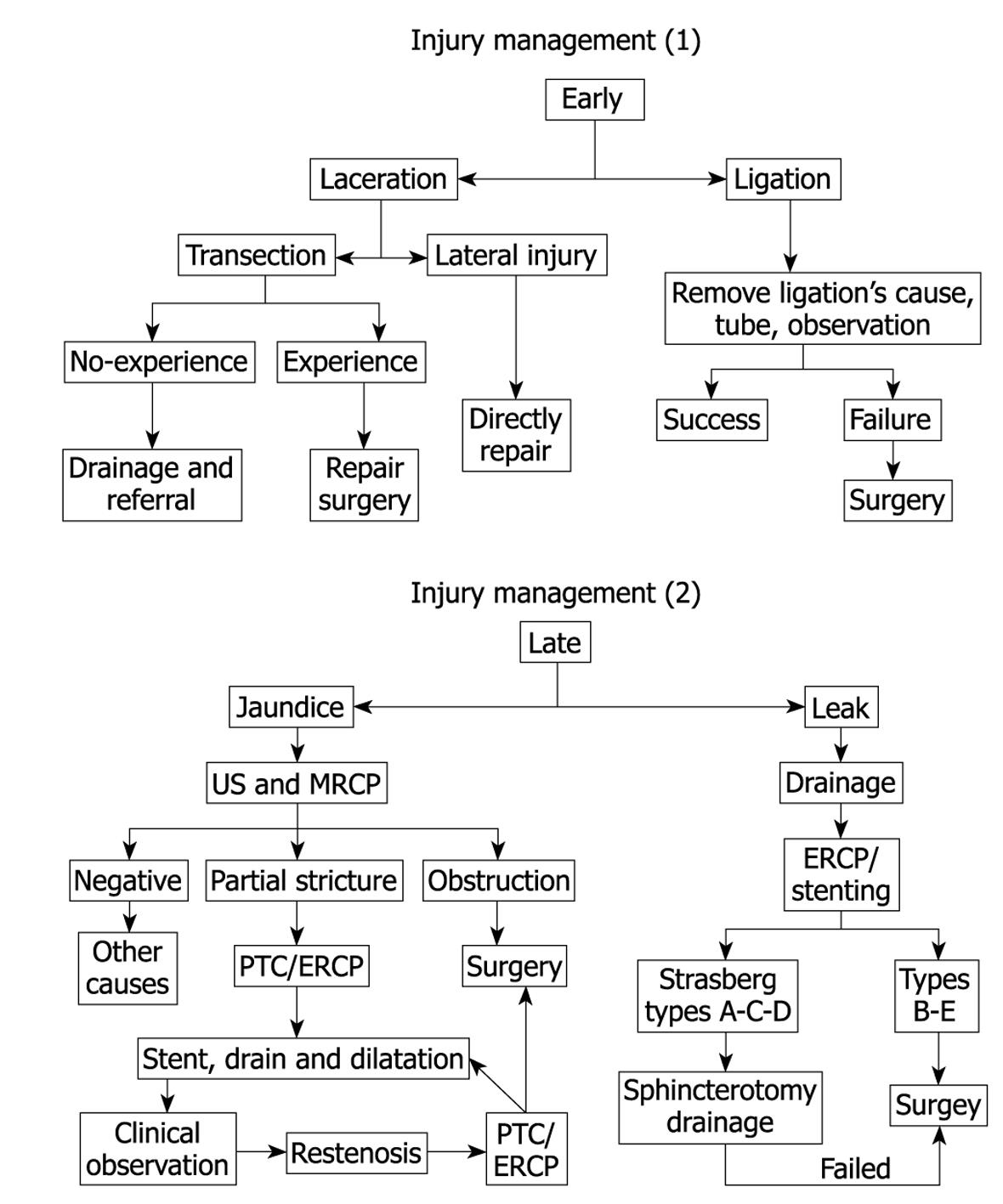

We propose an algorithm (Figure 5) for the treatment of early and late biliary complications. We consider complications that appeared during the first month postoperatively as early (usually leaks), and those presenting after one month as late complications (usually strictures).

Bile duct injuries are serious surgical complications. A major study led by Cameron showed post-repair mortality of 1.7%, with a similar percentage of patients dying before repair, as a result of sepsis. The study of Cameron also showed a complication rate after repair of 42.9%, despite an early referral to a specialist center[12]. Long-term outcome after repair showed good results in > 90% of cases[8].

In conclusion, biliary tract injuries are sometimes difficult to recognize, even for experienced surgeons. In the absence of an experienced surgeon, it is mandatory to limit the surgical manipulation to simple drainage, and to refer the patient to a more specialized center, in order to give the best chance for definitive treatment.

| 1. | Doganay M, Kama NA, Reis E, Kologlu M, Atli M, Gozalan U. Management of main bile duct injuries that occur during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:216. |

| 2. | Richardson MC, Bell G, Fullarton GM. Incidence and nature of bile duct injuries following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: an audit of 5913 cases. West of Scotland Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy Audit Group. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1356-1360. |

| 3. | Nuzzo G, Giuliante F, Giovannini I, Ardito F, D'Acapito F, Vellone M, Murazio M, Capelli G. Bile duct injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: results of an Italian national survey on 56 591 cholecystectomies. Arch Surg. 2005;140:986-992. |

| 4. | Lau WY, Lai EC. Classification of iatrogenic bile duct injury. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2007;6:459-463. |

| 5. | Tantia O, Jain M, Khanna S, Sen B. Iatrogenic biliary injury: 13,305 cholecystectomies experienced by a single surgical team over more than 13 years. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1077-1086. |

| 6. | Strasberg SM, Hertl M, Soper NJ. An analysis of the problem of biliary injury during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;180:101-125. |

| 7. | Bismuth H, Majno PE. Biliary strictures: classification based on the principles of surgical treatment. World J Surg. 2001;25:1241-1244. |

| 8. | Gouma DJ, Obertop H. Management of bile duct injuries: treatment and long-term results. Dig Surg. 2002;19:117-122. |

| 9. | Krähenbühl L, Sclabas G, Wente MN, Schäfer M, Schlumpf R, Büchler MW. Incidence, risk factors, and prevention of biliary tract injuries during laparoscopic cholecystectomy in Switzerland. World J Surg. 2001;25:1325-1330. |

| 10. | Walsh RM, Vogt DP, Ponsky JL, Brown N, Mascha E, Henderson JM. Management of failed biliary repairs for major bile duct injuries after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:192-197. |

| 11. | Chaudhary A, Chandra A, Negi SS, Sachdev A. Reoperative surgery for postcholecystectomy bile duct injuries. Dig Surg. 2002;19:22-27. |

| 12. | Sicklick JK, Camp MS, Lillemoe KD, Melton GB, Yeo CJ, Campbell KA, Talamini MA, Pitt HA, Coleman J, Sauter PA. Surgical management of bile duct injuries sustained during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: perioperative results in 200 patients. Ann Surg. 2005;241:786-792; discussion 793-795. |

| 13. | Tzovaras G, Peyser P, Kow L, Wilson T, Padbury R, Toouli J. Minimally invasive management of bile leak after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. HPB (Oxford). 2001;3:165-168. |