INTRODUCTION

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis (EG) is an uncommon inflammatory disease characterized by eosinophilic infiltration of the gastrointestinal tract[1–5]. In 1937, Kaijser first described the disease in two patients with syphilis who were allergic to neoarsphenamine[5]. More than 300 cases have been reported in the literature since 1937[1–10]. The disease affects all races and any age group from infancy to old age, although in adults, it usually presents in the third to fifth decade[1–4].

It is reported to be more common in men with a ratio of 3:2[1–4]. Any part of the gastrointestinal tract from the esophagus to rectum may be involved. Eosinophilic proctocolitis is almost exclusively seen in children[1–4]. Although the exact etiology is unknown, a personal or family history of food allergies and atopic disorders can be elicited in 50% to 70% of cases[1–4]. Almost all patients have tissue eosinophilia; many have peripheral eosinophilia and raised IgE levels. The majority of cases have a favorable response to steroids, suggesting a type-1 hypersensitivity reaction. Eosinophils are bilobed granulocytes with secondary granules produced in the bone marrow under the influence of interleukin-3 (IL-3), IL-5 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)[1–4]. Eosinophils primarily reside in the lining of the gastrointestinal tract providing protection against parasitic infections. The basic pathophysiological defect in EG is believed to be an alteration in the mucosal integrity, resulting in localization of various antigens in the gut wall and inducing tissue and blood eosinophilia[1–41011]. Specific food antigens can cause mast cell degranulation in the gastrointestinal wall, releasing eosinophil chemotactic factors, leukotrienes and other platelet activating factors[12–16]. The degranulation of eosinophils causes the release of histamine, cationic proteins like major basic protein, eosinophil peroxidase, eosinophil-derived neurotoxin and cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α. Cytokines like GM-CSF, IL-3 and IL-5 induce eosinophil proliferation and differentiation in the bone marrow, and are strong chemotactic agents that attract eosinophils to sites of tissue inflammation[13–16]. These proteins promote inflammation, tissue damage and further mast cell degranulation, resulting in a vicious circle[10–14]. Eotaxin, a novel 73-amino-acid chemokine, plays a central role in the recruitment of eosinophils into tissues[10–16]. Eotaxin is a specific eosinophil chemoattractant produced by epithelial cells at the site of inflammation. It induces aggregation of eosinophils and promotes their adhesion to endothelial cells[2915]. Some cases of EG are associated with unrecognized parasitic infestations and allergic or toxic reactions to drugs. An outbreak of eosinophilic enterocolitis due to the canine hookworm Ankylostoma canium was reported in Queensland, Australia[1718]. Drugs such as gold, azathioprine, carbamazepine, enalapril, clofazimine and co-trimoxazole have been reported to cause eosinophilia with variable involvement of the gastrointestinal tract[1920]. The clinical presentations of EG are protean[1–510] and may vary depending on the location and depth of involvement of the different layers of the digestive tract. On the basis of predominant involvement, Talley et al[7] and Klein et al[21] have classified eosinophilic gastroenteritis into mucosal, submucosal (muscular) and serosal disease. Mucosal disease is the most common (25%-100%) and presents with nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea and weight loss[1–5]. Muscular disease is the next most common (13%-70%) and presents with intermittent obstructive symptoms and complications such as perforation or aspiration. Serosal disease is less common (12%-40%). Intense peripheral eosinophilia, eosinophilic ascites and prompt response to steroid therapy are the hallmarks of serosal disease[1–7]. Rarely, EG may involve the pleura, pericardium, urinary bladder, pancreas, gall bladder, spleen, liver and the biliary tree[1–5910].

The diagnosis is established by demonstrating eosinophilic infiltration on biopsies obtained on endoscopy, laparoscopy or laparotomy. Multiple biopsies are required because of the patchy nature of the disease[15811]. Full-thickness surgical biopsies may be required for accurate diagnosis, if the disease process is confined to the muscle layer. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay has been developed in Australia to diagnose Ankylostoma canium infestation[1718]. Barium studies, CT scanning and ultrasonography may all reveal thickening of the mucosal folds with or without nodular filling defects or gastric outlet obstruction. The CT scan may also demonstrate ascites, pleural effusions and lymphadenopathy in some cases[7820]. The endoscopic findings may be patchy and vary from normal mucosa to mild erythema, thickened mucosal folds, nodularity and frank ulceration[157–9]. Corticosteroids remain the mainstay of treatment for EG. Some patients may have a relapsing course that requires long courses of steroid therapy.

CASE REPORT

Case 1

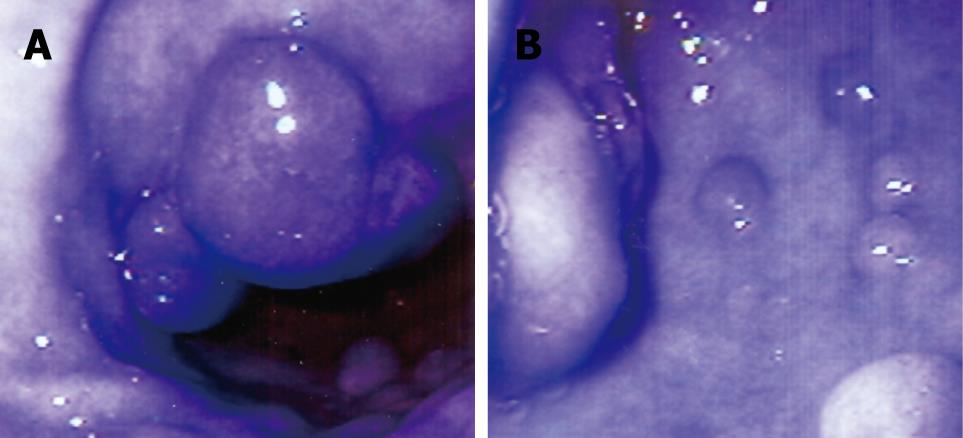

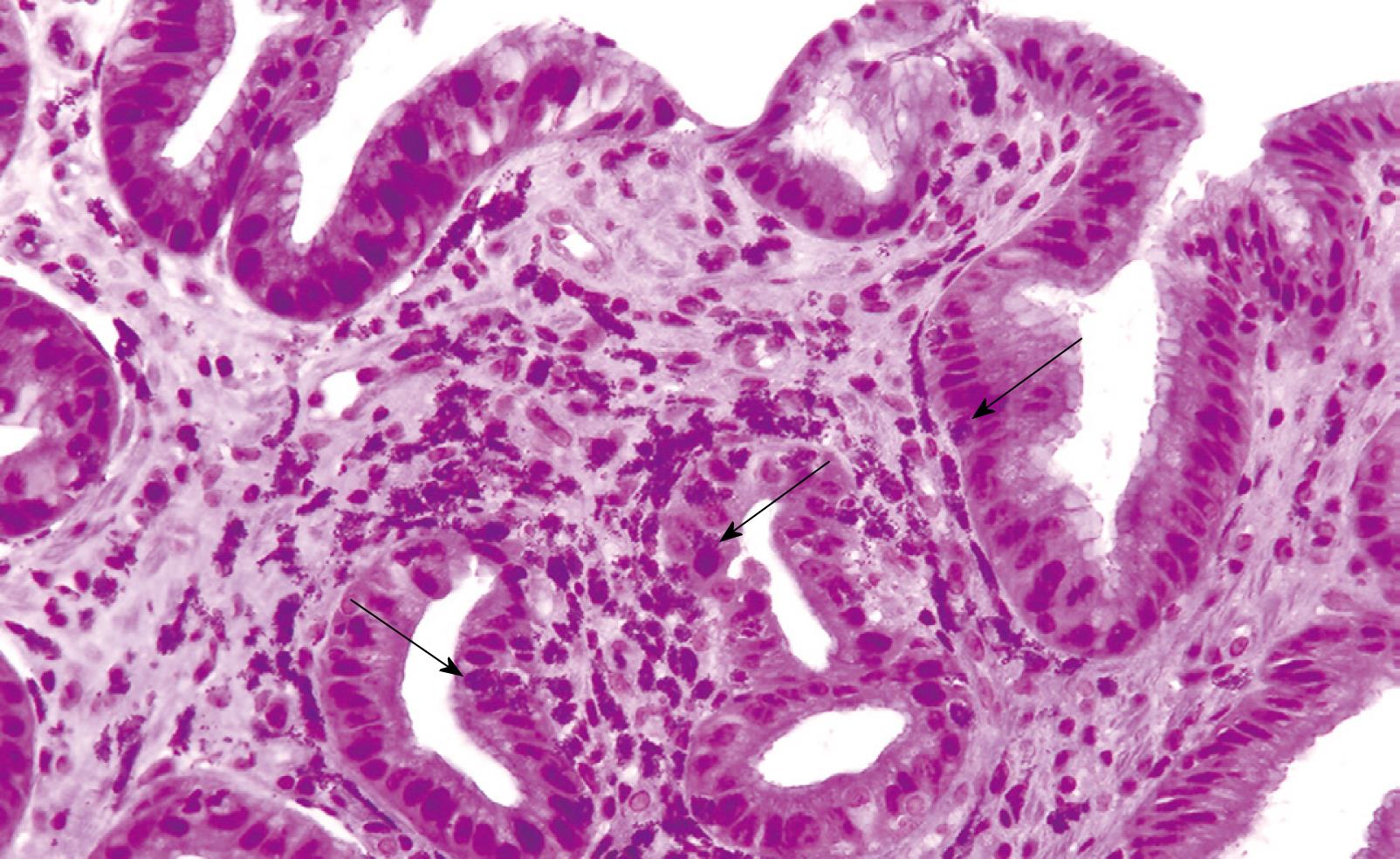

A 71-year-old woman presented with a history of nausea, abdominal pain, a weight loss of 10 pounds and diarrhea for 2 years. Stools studies were negative for ova, parasites and common pathogens. Clinical examination was unremarkable except for upper abdominal tenderness. A complete blood count revealed a WBC count of 6000/mm3 with an eosinophil count of 8.2% (normal 0% to 4%). Other laboratory tests were unremarkable. The serum IgE level was 26 U/mL (normal 6-12 U/mL) and RAST testing for a battery of allergens, including common foods, was negative. CT scan of the abdomen was normal. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) revealed distal esophagitis. There were multiple polypoid nodules in the gastric antrum, varying from 0.5 to 1 cm in size (Figure 1). Thickened gastric mucosal folds, antral erythema with small ulcers and erythema of the duodenal bulb were also noted. Histological examination of the polypoid nodules and biopsies from the esophagus, gastric antrum and duodenum demonstrated heavy eosinophilic infiltration and numerous degranulated eosinophils (Figure 2). Colonoscopy and random biopsies from the colon were normal. The patient was treated with prednisone 40 mg/d for 6 wk and tapered down to a maintenance dose of 10 mg/d for 6 mo, without much improvement in her symptoms. Repeat EGD revealed healing of the antral ulcers, without any change in the size and endoscopic appearance of the gastric polypoid lesions. Repeat biopsies revealed eosinophilic infiltration as before, with more fibrosis. Sodium cromoglycate 200 mg tid was added to her treatment with modest improvement of her symptoms. However, her abdominal pain recurred and she reported worsening nausea, postprandial fullness and bloating over the next 6 mo. Endoscopic examination revealed an increase in the number and size of the polypoid lesions, especially in the antrum, causing partial gastric outlet obstruction. Histological examination of the polypoid lesions demonstrated marked fibrosis but significantly decreased eosinophilic infiltration. Her obstructive symptoms worsened requiring antrectomy and gastrojejunostomy. She did well after surgery on low-dose steroids and sodium cromoglycate.

Figure 1 Endoscopic appearance of stomach (A and B) showing multiple gastric antral polyps of 4-10 mm in size and antral mucosal erythema.

Figure 2 Histological appearance of the gastric polyp showing eosinophilic infiltration of the lamina propria by numerous degranulated eosinophils and some polymorphonuclear cells (arrows).

Some intraepithelial eosinophils are also seen. (HE, × 200).

Case 2

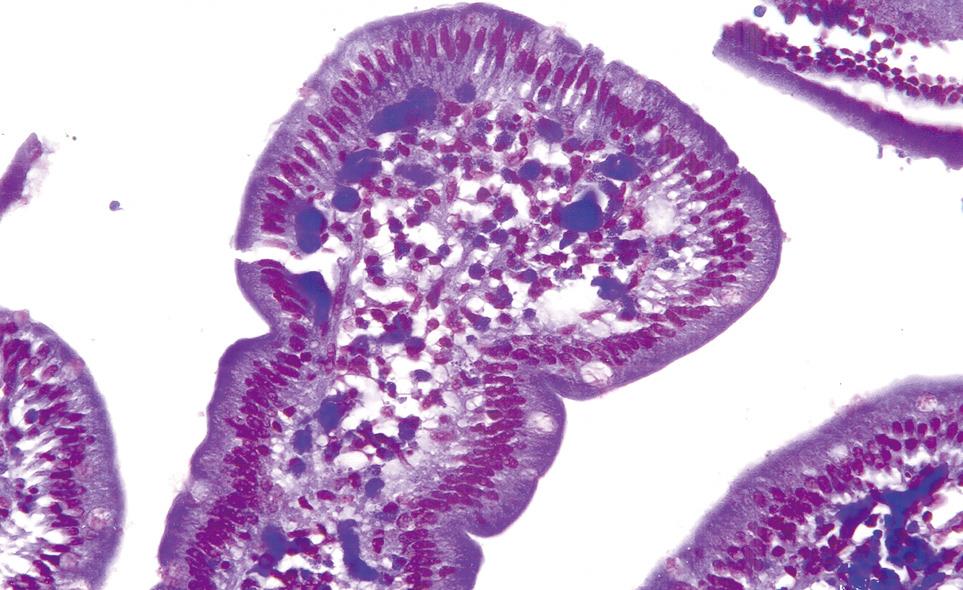

A 57-year-old man presented with a history of generalized aches, nausea and upper abdominal pain for 4 mo. He was treated with H-2 blockers and later switched to proton pump inhibitors. His symptoms worsened and he developed postprandial fullness and bloating. His past medical history was remarkable for an episode of self-limiting pancreatitis of unclear etiology. He had no personal or family history of allergic disorders. Clinical examination demonstrated mild abdominal distension and epigastric tenderness. Laboratory data revealed, a WBC count of 10 000/mm3, and an eosinophil count of 33% (normal 0%-1%). The serum amylase level was 94 U/L (normal 25-115 U/L) and serum lipase was 415 U/L (normal 114-286 U/L). Stool studies for ova and parasites were negative. Barium X-ray series of the upper gastrointestinal tract revealed retained gastric secretions and narrowing of the gastric outlet with features of gastric outlet obstruction. Endoscopic examination demonstrated thickened and erythematous antral and duodenal folds with pyloric channel and duodenal narrowing. The gastric and duodenal biopsies revealed subacute and chronic inflammation with moderately intense eosinophilic infiltration (Figure 3). A CT scan of the abdomen demonstrated thickened pyloric and duodenal folds and unremarkable pancreas. The patient responded well to a course of oral steroids and his symptoms continued to improve on maintenance steroids.

Figure 3 Histological appearance of duodenal mucosal biopsy demonstrating moderately severe infiltration with eosinophils and some intraepithelial eosinophils.

(HE, × 200).

Case 3

A 74-year-old man presented with intermittent bloating and fullness after meals for 3 years. He also complained of intermittent nausea and vomiting, abdominal pain and diarrhea. His symptoms had worsened over the past year and he had lost 10 pounds in weight. His past medical history was remarkable for an attack of pancreatitis of unclear etiology. He had no personal or family history of allergic disorders. Clinical examination was unremarkable except for mildly distended and tender abdomen. Laboratory tests revealed a WBC count of 6000/mm3, and an eosinophil count of 9.6% (normal 0% to 4%). Serum IgE level was 54 U/mL (normal 6-12 U/mL). Stools studies were negative for ova and parasites. Barium X-rays of the upper gastrointestinal tract showed features of gastric outlet obstruction and irregular narrowing at the level of the second and third portion of the duodenum, with contrast medium refluxing into the common bile duct (Figure 4). A CT scan of the abdomen confirmed the presence of stenosis at the level of the second and third portion of the duodenum. An EGD revealed mild esophagitis and a dilated stomach and retained food. The antrum and proximal duodenal bulb were erythematous. There was mild narrowing at the level of the pylorus but significant narrowing of the duodenal bulb. The endoscope could not be advanced further. Biopsies from the antrum and the bulb showed moderately intense eosinophilic infiltration. Colonoscopy showed diverticular disease and random colonic biopsies revealed moderately intense eosinophilic infiltration. The patient did not accept steroid therapy or endoscopic dilatation initially. He had only partial improvement of symptoms with sodium cromoglycate 200 mg tid. His symptoms persisted and he agreed to steroid therapy. He responded well to a 6-wk course of prednisone 40 mg/d, tapered down to a maintenance dose of 10 mg/d.

Figure 4 Barium upper GI demonstrating stricture and stenosis of the second and third part of duodenum, with reflux of the contrast medium into the biliary tree.

Case 4

A 43-year-old African American man was admitted with a history of intermittent abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea for 3 mo. He had experienced postprandial fullness and bloating for the past month and lost 8 pounds in weight. He had used ranitidine and omeprazole without benefit. He had no history of food allergies and his mild asthma was controlled by serevent inhalation. His clinical examination was remarkable for dehydration, abdominal distension and mild upper abdominal tenderness. Laboratory tests on admission revealed a WBC count of 6400/mm3 with an eosinophil count of 20% (normal 0%-4%). Serum amylase was 471 U/L (normal 25-115 U/L) and serum lipase was 1785 U/L (normal 114-286 U/L). Serum IgE level was 650 U/L (normal < 140 U/L). Other laboratory tests including liver function tests, routine stool studies, serum lipid profile and serum immunoglobulins, were normal. An ultrasound and CT scan of the abdomen revealed a dilated stomach with retained food and mild thickening of the antral and duodenal folds. The pancreas was normal and there were no gallstones. The patient was treated conservatively with rehydration and nasogastric suction. EGD showed mild distal esophagitis, multiple antral erosions and thickened antral folds with antro-pyloric narrowing. Multiple 2-6-mm ulcerated nodules were noted in the duodenal bulb, with thickening of the duodenal folds extending into the second part of the duodenum. Biopsies of the esophagus revealed esophagitis with mild eosinophilic infiltration. Biopsies of the antrum and duodenum showed chronic gastritis and duodenitis with intense eosinophilic infiltration of the lamina propria and submucosa. Colonoscopy showed mild patchy erythema and biopsies showed mild eosinophilic infiltration in the lamina propria. The patient was treated with steroids. His eosinophil count normalized and his symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction resolved. His symptoms recurred on tapering down the steroids. Sodium cromoglycate was added to his therapy and helped in tapering down his steroids. After 6 mo of maintenance steroid therapy, he stopped the treatment and is doing well.

Case 5

A 60-year-old Indian woman was admitted with a history of upper abdominal pain for 3 wk, associated with nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. She had mild asthma controlled by albuterol inhalation. She was a teetotaller. Clinical examination was unremarkable except for mild upper abdominal tenderness. Laboratory data revealed a serum amylase of 375 U/L (normal 25-115 U/L) and serum lipase of 1115 U/L (normal 114-286 U/L). Complete blood count was remarkable for a WBC count of 12 500/mm3 and an eosinophil count of 17% (normal 0%-4%). Other laboratory data including liver function tests, routine stool studies, serum lipid profile and serum immunoglobulins were normal. A CT scan of the abdomen was unremarkable. The patient was treated conservatively for a clinical diagnosis of acute idiopathic pancreatitis. However, she continued to have abdominal pain and diarrhea and lost about 20 pounds in weight over the next 5 wk. An endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatographic examination was normal except for prominent and erythematous ampulla. Brushings from the intra-ampullary pancreatic duct were normal and biopsies of the ampulla revealed dense eosinophilic infiltration with mild reactive glandular proliferation. An EGD showed distal esophagitis, antral gastritis and duodenitis with narrowing of the antrum and duodenal bulb. Biopsies revealed chronic esophagitis and gastritis with moderate eosinophilic infiltration, and severe chronic duodenitis with intense eosinophilic infiltration. The patient was treated with a course of steroids and responded promptly with resolution of symptoms and weight gain. She was maintained on a low dose of maintenance steroids for 3 mo. She was subsequently tapered off the steroids and is doing well.

DISCUSSION

These five patients presented had unusual manifestations of EG, testifying to the varied presentations of this disorder[1–57–9]. Two of five patients (40%) had a significant personal history of allergic disorders (asthma) and none had a history of food allergy. In a review of 220 cases, Naylor reported a history of allergy in 52% of cases[8]. Food allergy has been reported to be present in 50% of cases[1–52122]. All five of our cases had abdominal pain and diarrhea, which are the most common symptoms in patients with EG being present in 72% and 50% of cases, respectively[1–57–9]. All five of our cases had predominant involvement of the stomach and duodenum, resulting in gastric outlet and duodenal obstruction. In the past, benign diseases such as peptic ulcer disease accounted for most of the cases of gastric outlet obstruction. With the evolution of effective therapy for peptic ulcer disease, malignancy and EG have emerged to be the most important causes of gastro-duodenal obstruction[23–26]. It is therefore imperative to rule out EG and malignancy in these patients. In children, EG may mimic congenital pyloric stenosis[24]. Other uncommon causes of gastric outlet obstruction including Crohn’s disease, post-surgical strictures, pancreatic pseudocyst, gallstones and chronic pancreatitis should also be considered in the differential diagnosis. Weight loss, especially in elderly patients, should heighten the suspicion for malignancy. A long history of symptoms, unremarkable CT scan and normal tumor markers may be helpful in ruling out a malignant etiology.

All five of our cases (100%) had endoscopic and histological evidence of eosinophilic gastritis and duodenitis. Endoscopic and histological evidence of eosinophilic esophagitis was present in four of our five (80%) cases and one patient did not have esophageal biopsies performed. Colonoscopy and random colonic biopsies were performed in three cases and revealed eosinophilic colitis in two (66%). Although EG can involve the entire gastrointestinal tract, the esophagus and colon are uncommonly involved[1–526]. However, esophageal involvement is now more frequently reported, especially in children and young adults[1–5].

In a review of 220 cases, Naylor et al[8] reported that the stomach was the most frequently involved organ (43% of cases). The duodenum and the rest of the small bowel are less frequently involved. Small bowel involvement may present with abdominal pain, diarrhea or frank malabsorption[2728], and rarely bowel obstruction[1–57–929–31]. There have been only a few case reports of jejunal and ileal strictures[2526]. Colonic involvement presents as abdominal pain and/or diarrhea[91129–31].

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis may present as an acute abdomen due to acute pancreatitis, intestinal or colonic obstruction, intussusception and perforation[252631–33]. Two of our five cases (40%) presented with acute pancreatitis of unknown etiology. Interestingly, the two cases with acute pancreatitis had very high eosinophil counts, and biopsies from a prominent and erythematous ampulla in one patient showed intense eosinophilic infiltration. There was no recurrence of pancreatitis after steroid treatment, supporting eosinophilic infiltration as the etiology. The barium X-rays of one of the patients with a history of pancreatitis revealed an interesting finding of spontaneous barium reflux into the biliary tree (Figure 4). We believe the duodenal stricture from EG facilitated the reflux of barium into the biliary tree. Eosinophilic infiltration can cause edema, fibrosis and distortion in the ampulla and peri-ampullary duodenum and cause pancreatitis[3334]. Pancreatic involvement may also mimic a pancreatic malignancy[3334]. Hepatic, splenic, biliary tract, gall bladder and urinary bladder involvement has also been reported[1–57–934–37].

The peripheral eosinophil count was high in all five (100%) of our cases and very high in two cases. Peripheral eosinophilia has been reported in up to 80% of cases[1–57]. Patients with predominantly serosal disease have higher absolute eosinophil counts (average 8000/dL) than patients with mucosal disease (average 2000/dL) and muscle layer disease (average 1000/dL)[3334]. None of our cases had evidence of significant blood loss or malabsorption, which have been reported in the literature in 20%-30% patients, especially those with mucosal disease[6–8]. Serum IgE level was checked in only three of our patients and was elevated in two (66%). IgE levels are more likely to be high in children with EG than in adults[3536]. Our patients demonstrated almost the whole spectrum of endoscopic features including, erythema, ulcers, nodularity, thickening of folds and pseudopolypoid lesions.

All five of our patients (100%) responded to steroid therapy. Only one patient required surgery for gastric outlet obstruction. One of our patients had a partial response to sodium cromoglycate and in another patient this drug helped in tapering off his steroids. Steroids are the mainstay of treatment in EG and about 90% patients respond to this therapy[57–9]. Patients with serosal disease usually show a dramatic response to steroids[1–57–9]. Azathioprine may be helpful as a steroid-sparing agent in patients requiring high doses for maintenance. Sodium cromoglycate is a mast cell stabilizer that prevents release of toxic mediators like histamine, platelet activating factors and leukotrienes from mast cells. There have been several reports of a beneficial response to this drug[3839]. The usual dose is 200 mg three or four times per day. Ketotifen is similar to sodium cromoglycate in its biological profile and may be useful in some cases[40]. Elimination of presumed dietary articles is unhelpful in most cases[1–5]. Successful treatment of EG with montelukast, a leukotriene modifier, has been reported[12]. Suplatast tosilate is a new IL-4 and IL-5 inhibitor effective in treating asthma, and has been reported to be useful in treating a patient with EG[41]. A humanized anti-IL-5 monoclonal antibody (mepolizumab) has been found to be beneficial in a small series of four patients with hypereosinophilia syndrome[42]. This antibody may have a potential therapeutic role in treating patients with EG.

As demonstrated by our five cases, the clinical course of EG is highly variable. However, the long duration of illness in most cases testifies to the generally good prognosis of EG. Fatalities from EG are rare and are usually due to perforation of the gastrointestinal tract[4344].

From our experience with these five cases, we conclude that EG is truly protean in its clinical and endoscopic manifestations, sites of involvement in the digestive system, response to therapy and clinical course. Gastroduodenal involvement is common, esophageal involvement is being increasingly reported and colonic involvement is uncommon. EG can present with gastric outlet and duodenal stricturing resulting in gastric outlet obstruction. Malignancy is an important differential diagnosis and should be ruled out by appropriate diagnostic modalities. Patients with EG may present with acute pancreatitis and this should be considered in the differential diagnosis. The course of EG is variable and relapses are common. However, the response to treatment and overall prognosis is good.