Published online Apr 21, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1906

Revised: March 18, 2009

Accepted: March 25, 2009

Published online: April 21, 2009

Hepatobiliary cystadenoma is an uncommon lesion that is most often found in middle-aged women and difficult to diagnose preoperatively. Here, we report a case of giant hepatobiliary cystadenoma in a male patient with obvious convex papillate. On the basis of imaging examinations, the patient was diagnosed as hepatobiliary cystadenoma prior to operation. Left hepatectomy was performed and the patient was symptom-free during a 6-mo follow-up period, suggesting that imaging examination is the major diagnostic method of hepatobiliary cystadenoma, and operation is its best treatment modality.

- Citation: Qu ZW, He Q, Lang R, Pan F, Jin ZK, Sheng QS, Zhang D, Zhang XS, Chen DZ. Giant hepatobiliary cystadenoma in a male with obvious convex papillate. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(15): 1906-1909

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i15/1906.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.1906

Hepatobiliary cystadenoma is an uncommon lesion, which is mainly seen in females. No more than 10 male cases were reported in the world literature prior to 2005[1]. It is difficult to make an accurate diagnosis of hepatobiliary cystadenoma before surgery. We recently treated a male with a preoperative diagnosis of hepatobiliary cystadenoma. We, in this paper, report this case to elucidate its clinical presentation, preoperative evaluation and treatment. To the best of our knowledge, such a case with obvious convex papillate has very rarely been reported in the literature.

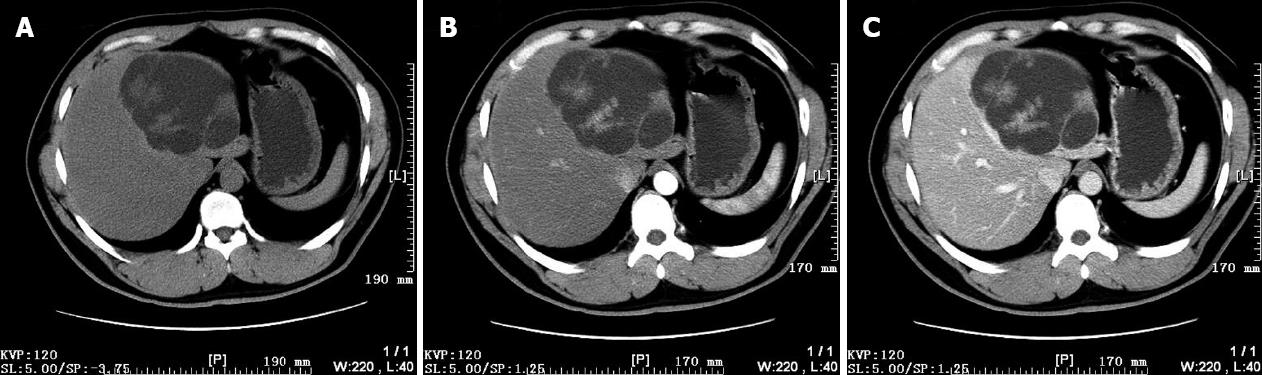

A 35-year-old man was admitted because of a multilocular cyst in his liver detected by computerized tomography (CT) during the course of health examination 2 wk ago. His past medical history was unremarkable. Physical examination was negative at admission. Laboratory tests were within normal limits, serology for hepatitis B infection was negative, and serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels were normal. CT showed an area measuring 11 cm × 9 cm in which multiple density areas were grouped together. The internal septations and convex papillate were visible, and enhanced after intravenous administration of contrast medium (Figure 1).

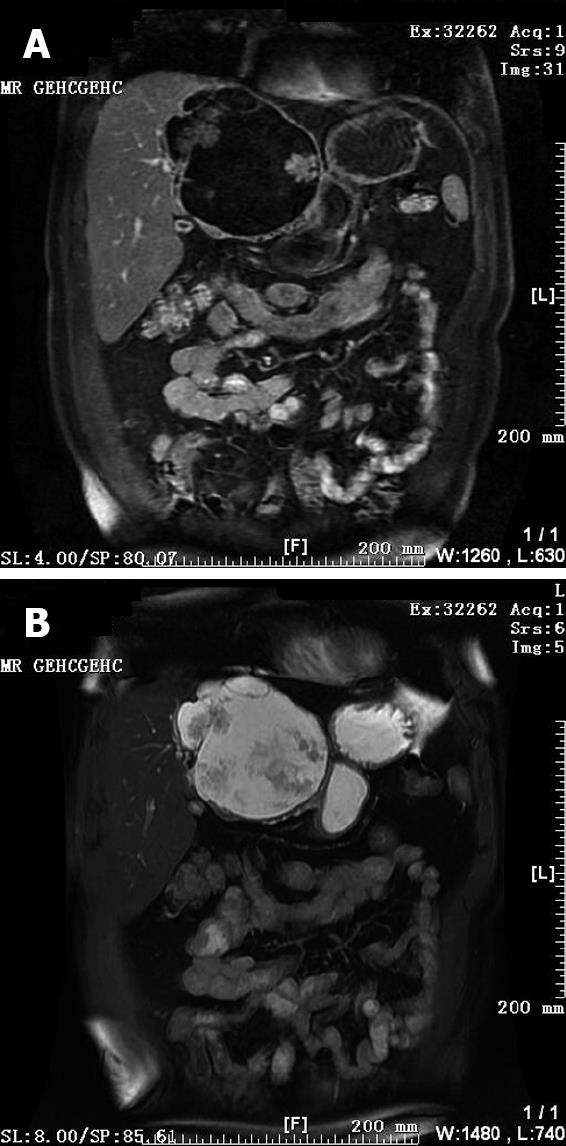

Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a large cystic tumor measuring approximately 10 cm in diameter originating from the left liver lobe. On T1-weighted images (T1WI), low signal intensity was apparent within the cystic spaces. On corresponding T2-weighted images (T2WI), the tumor was characterized by a medium-high intensity signal clearly delineated from the surrounding liver tissue with internal septal structures separating the fluid-filled spaces (Figure 2). On the basis of these findings, the patient was diagnosed with a hepatobiliary cystadenoma.

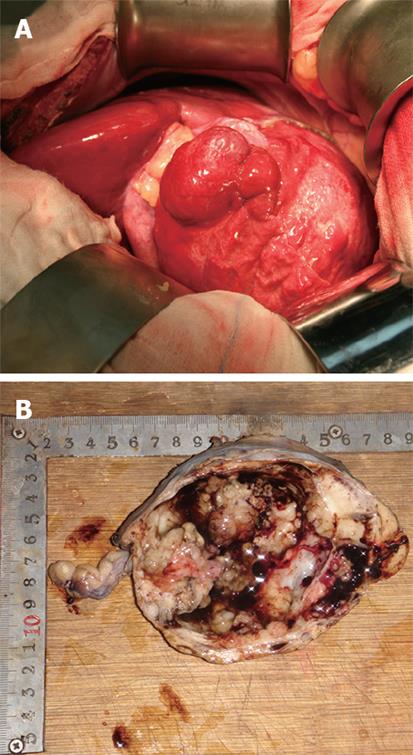

Left hepatectomy was performed (Figure 3A). On gross examination, the resected specimen showed a multilocular cystic lesion with a solid part measuring 12 cm × 9 cm × 9 cm (Figure 3B). The cyst contained mucinous fluid with no connection to the bile duct. CT and MRI showed papillary projections inside the cyst.

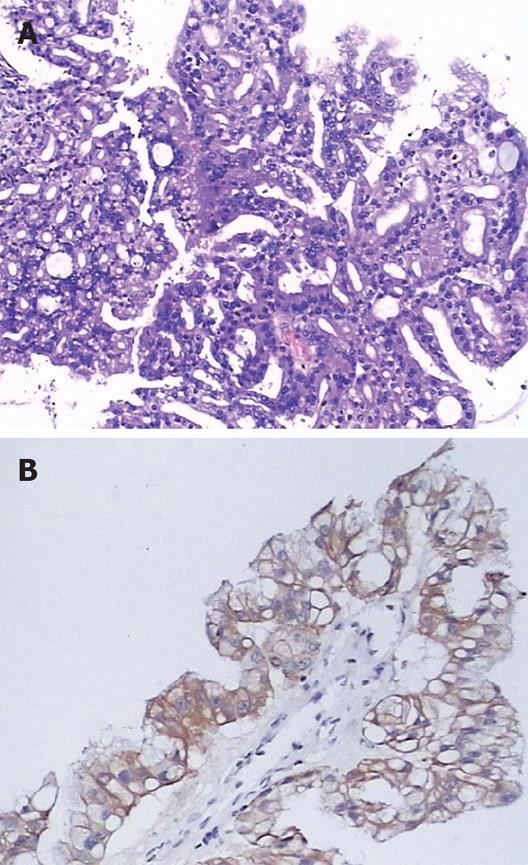

Histological examination revealed the cystic wall, most of which was lined with a single layer of columnar and cuboidal cells. The cells were not pleomorphic (Figure 4A). The epithelium showed strong and diffuse cytoplasmic staining with antibodies to CK7, CK8, CK18, and CK19 (Figure 4B), but was negative for AFP, CEA and CK20. Ki-67 labeling index was lower than 5%. A final diagnosis of hepatobiliary cystadenoma was established.

The patient was discharged on day 9 after surgery. No evidence of recurrence was found during the 6-mo follow-up period.

Hepatobiliary cystadenoma is rare neoplasm that arises in the liver, or less frequently in the extrahepatic biliary system, accounting for less than 5% of all cystic neoplasms found in the liver[2]. However, it is believed to be premalignant. Because its rarity and cystic aspect are similar to other cystic liver lesions[3], diagnosis is often delayed and may result in inaccurate treatment modalities, such as aspiration, thus further causing unnecessary morbidity and mortality[4]. Sometimes, a two-stage operation is needed, due to misdiagnosis of the disease[5].

The lesion is mainly seen in females and more than 80% of the reported patients are over 30 years of age[2]. Our patient was a male. No more than 10 male cases were reported in the world literature prior to 2005[1]. This lesion is usually located in the right lobe of liver[6]. However, all the cases reported by Lewin were found in the left lobe of liver[7]. In our patient, the lesion was also located in the left lobe of liver.

Clinical manifestations of the tumor are non-specific. The chief complaints are usually an abdominal mass, abdominal pain and distension. When the tumor compresses the porta hepatis or the extrahepatic bile duct, obstructive jaundice may occur[8]. Nevertheless, some patients are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally at imaging examination, like ours. Thus, clinical manifestations are considered less reliable in the diagnosis of hepatobiliary cystadenoma.

Laboratory results are normal in most patients with hepatobiliary cystadenoma, though serum liver enzyme levels may be mildly elevated occasionally. Serum alpha-fetoprotein and CEA levels are usually within the normal range. It was recently reported that CA 19-9 may be elevated in the cystic fluid and contributes to the diagnosis of hepatobiliary cystadenoma before operation; but, carcinomatosis may occur following cyst aspiration or biopsy[9]. It has been shown that serum CA 19-9 level can be used as a parameter of tumor activity during follow-up after resection[10]. In another high CA 19-9 level may be related to focal dysplasia of epithelial cells[11]. For this reason, the presence of elevated CA 19-9 level cannot be considered a significant parameter for the discrimination between malignant and benign hepatic tumors.

Imaging examination is the key to the diagnosis of hepatobiliary papillary cystadenoma. Preoperative imaging examination, particularly CT and MRI, plays an important role in recognizing and characterizing the disease. Patients are often incidentally diagnosed by imaging examination. The typical CT features of cystadenoma are usually a well-defined mass with low-density and internal septa. Its fibrous capsule and internal septations are often visible and help distinguish the lesion from a simple cyst. The convex papillate can be seen on the septation, although it is more common in cystadenocarcinoma. Bile duct dilatation commonly results from extrinsic compression. Calcifications along the wall and internal septum are uncommon. Unilocular lesions have been reported[1213], and are often incorrectly diagnosed as a simple cyst, thus resulting in inadequate therapy[2]. Contrast CT demonstrates enhanced internal septations and mural nodules. MRI may improve tissue characterization because of its high contrast resolution. Signal intensity may vary depending on the property of cyst fluid[1314]. On T1WI, the signal intensity may increase with protein concentration. The signal intensity of serous fluid and bile is low. In rare cases, the intensity of serous cystic content can be raised by intracystic hemorrhage and fluid-fluid level can be present[3]. On T2WI, septations with low signal intensity are better visualized in contrast to the high signal intensity of cystic fluid. Kubo et al[15] reported that monitoring changes in radiological appearance of the tumor may be useful for the differential diagnosis of cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), even if rarely employed, may show a cystic cavity communicating with the biliary tree[4].

According to their histology, cystadenoma is classified into two subgroups: cystadenoma with and without mesenchymal stroma. Hepatobiliary cystadenoma without mesenchymal stroma can cause malignant alterations, to which our case belongs. The prognosis of patients, especially male patients with hepatobiliary cystadenoma is poor[16]. Because of its malignant potential, natural history of progressive enlargement and recurrence after partial excision[17], total excision of the cyst with a wide margin (> 2 cm) of normal liver tissue is widely supported.

In summary, our experience demonstrates that imaging examination contributes to the diagnosis of hepatobiliary cystadenoma before operation. Complete excision is its best treatment modality.

| 1. | Kazama S, Hiramatsu T, Kuriyama S, Kuriki K, Kobayashi R, Takabayashi N, Furukawa K, Kosukegawa M, Nakajima H, Hara K. Giant intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma in a male: a case report, immunohistopathological analysis, and review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:1384-1389. |

| 2. | Ishak KG, Willis GW, Cummins SD, Bullock AA. Biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma: report of 14 cases and review of the literature. Cancer. 1977;39:322-338. |

| 3. | Seidel R, Weinrich M, Pistorius G, Fries P, Schneider G. Biliary cystadenoma of the left intrahepatic duct (2007: 2b). Eur Radiol. 2007;17:1380-1383. |

| 4. | Lempinen M, Halme L, Numminen K, Arola J, Nordin A, Mäkisalo H. Spontaneous rupture of a hepatic cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma: report of two cases. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2005;12:409-414. |

| 5. | Ramacciato G, Nigri GR, D'Angelo F, Aurello P, Bellagamba R, Colarossi C, Pilozzi E, Del Gaudio M. Emergency laparotomy for misdiagnosed biliary cystadenoma originating from caudate lobe. World J Surg Oncol. 2006;4:76. |

| 6. | Mortelé KJ, Ros PR. Cystic focal liver lesions in the adult: differential CT and MR imaging features. Radiographics. 2001;21:895-910. |

| 7. | Lewin M, Mourra N, Honigman I, Fléjou JF, Parc R, Arrivé L, Tubiana JM. Assessment of MRI and MRCP in diagnosis of biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:407-413. |

| 8. | Erdogan D, Busch OR, Rauws EA, van Delden OM, Gouma DJ, van-Gulik TM. Obstructive jaundice due to hepatobiliary cystadenoma or cystadenocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5735-5738. |

| 9. | Koffron A, Rao S, Ferrario M, Abecassis M. Intrahepatic biliary cystadenoma: role of cyst fluid analysis and surgical management in the laparoscopic era. Surgery. 2004;136:926-936. |

| 10. | Thomas JA, Scriven MW, Puntis MC, Jasani B, Williams GT. Elevated serum CA 19-9 levels in hepatobiliary cystadenoma with mesenchymal stroma. Two case reports with immunohistochemical confirmation. Cancer. 1992;70:1841-1846. |

| 11. | Kim K, Choi J, Park Y, Lee W, Kim B. Biliary cystadenoma of the liver. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1998;5:348-352. |

| 12. | Korobkin M, Stephens DH, Lee JK, Stanley RJ, Fishman EK, Francis IR, Alpern MB, Rynties M. Biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma: CT and sonographic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;153:507-511. |

| 13. | Buetow PC, Buck JL, Pantongrag-Brown L, Ros PR, Devaney K, Goodman ZD, Cruess DF. Biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma: clinical-imaging-pathologic correlations with emphasis on the importance of ovarian stroma. Radiology. 1995;196:805-810. |

| 14. | Gabata T, Kadoya M, Matsui O, Yamashiro M, Takashima T, Mitchell DG, Nakamura Y, Takeuchi K, Nakanuma Y. Biliary cystadenoma with mesenchymal stroma of the liver: correlation between unusual MR appearance and pathologic findings. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1998;8:503-504. |

| 15. | Kubo S, Kinoshita H, Hirohashi K, Yamamoto T. A case of cystadenocarcinoma of the liver. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1995;2:85-89. |

| 16. | Devaney K, Goodman ZD, Ishak KG. Hepatobiliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma. A light microscopic and immunohistochemical study of 70 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:1078-1091. |