Published online Mar 28, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1415

Revised: January 6, 2009

Accepted: January 6, 2009

Published online: March 28, 2009

The treatment of isolated segmental, sectoral and right hepatic bile duct injuries is controversial. Nineteen patients were treated over a 26-year period. Group one was comprised of 4 patients in whom the injury was primarily repaired during the original surgery; 3 over a T-tube, 1 with a Roux-en-Y. These patients had an uneventful recovery. The second group consisted of 5 patients in whom the duct was ligated; 4 developed infection, 3 of which required drainage and biliary repair. Two patients had good long-term outcomes; the third developed a late anastomotic stricture requiring further surgery. The fourth patient developed a small bile leak and pain which resolved spontaneously. The fifth patient developed complications from which he died. The third group was comprised of 4 patients referred with biliary peritonitis; all underwent drainage and lavage, and developed biliary fistulae, 3 of which resolved spontaneously, 1 required Roux-en-Y repair, with favorable outcomes. The fourth group consisted of 6 patients with biliary fistulae. Two patients, both with an 8-wk history of a fistula, underwent Roux-en-Y repair. Two others also underwent a Roux-en-Y repair, as their fistulae showed no signs of closure. The remaining 2 patients had spontaneous closure of their biliary fistulae. A primary repair is a reasonable alternative to ligature of injured duct. Patients with ligated ducts may develop complications. Infected ducts require further surgery. Patients with biliary peritonitis must be treated with drainage and lavage. There is a 50% chance that a biliary fistula will close spontaneously. In cases where the biliary fistula does not close within 6 to 8 wk, a Roux-en-Y anastomosis should be considered.

- Citation: Colovic RB. Isolated segmental, sectoral and right hepatic bile duct injuries. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(12): 1415-1419

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i12/1415.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.1415

Dangerous anatomy, dangerous pathologies and dangerous surgery are all factors which lead to bile duct injuries in both open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy[1] Dangerous anatomical variants of the right liver bile ducts are known to occur in around 15%-20% of patients, and may be injured during cholecystectomy. These operative sectoral and segmental bile ducts injuries (SSBDI) can often pass by unnoticed and without serious symptoms, and thus the frequency is likely to be far higher. They can however also lead to serious complications such as cholangitis and liver abscesses or biliary fistula and peritonitis.

The treatment of SSBDI is controversial, and the different approaches often depend on the timing of the diagnosis and the types of complications. This study reviews our management of SSBDI.

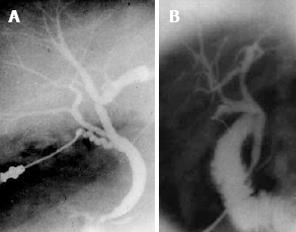

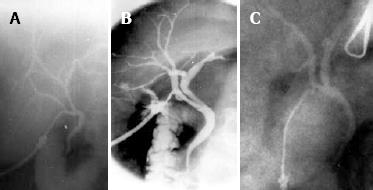

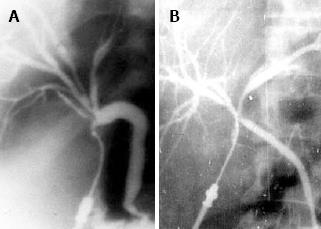

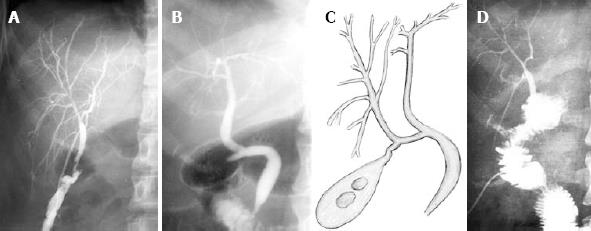

Dangerous anatomy, dangerous pathologies and dangerous surgery are all factors which lead to bile duct injuries in both open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy[1]. There are three main dangerous anatomical variants. Firstly, the cystic duct may be near to the segmental (Figure 1A), or sectoral bile duct (Figure 1B) so that these ducts may be injured during dissection, transection or occlusion of the cystic duct. Secondly, the cystic duct may join one of these ducts, instead of the common bile duct (Figure 2A-C) so that one of them may be misinterpreted as a cystic duct and so transected, resected and occluded. Thirdly, the cystic duct may join the convergence of the sectoral or hepatic ducts (Figure 3A and B) so that the common bile duct may be misinterpreted as a cystic duct and so transected and resected.

Dangerous anatomical variants of the right liver bile ducts are known to occur in around 15%-20% of patients, and may be injured during cholecystectomy. These operative isolated segmental, sectoral and right hepatic bile duct injuries can pass by unnoticed and without serious symptoms, and thus the frequency is likely to be even greater. They can however also lead to serious complications such as cholangitis and liver abscesses or biliary fistula and peritonitis. The treatment of isolated segmental, sectoral and right hepatic bile duct injuries is controversial, and the different approaches often depend on the timing of the diagnosis and the types of complications.

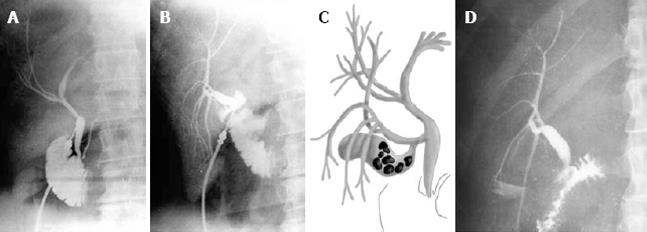

We retrospectively reviewed the management of isolated segmental, sectoral and right hepatic bile duct injuries treated in our centre over a 26 year period (1982-2008). The 19 patients (14 women, with a mean age of 51 years) were divided into 4 groups in order to better analyze the different approaches (Table 1). The first group was comprised of 4 patients in whom the injury was recognized at the time of original surgery. Each patient underwent a primary repair, 3 over a tiny T-tube inserted into the common bile duct and then passed through the anastomosis, and 1 patient had an anastomosis of the injured duct with a Roux-en-Y jejunal limb (Figure 4). All the 4 patients had an uneventful recovery and continue to remain well to this day.

| Patient number | Gender | Age | Injury recognised intra-op | Immediate intervention | Complication | Treatment for complication | Delayed treatment | Outcome | Late complication |

| 1 | F | 60 | Yes | Repair over a T tube | No | No | None | Excellent | None |

| 2 | M | 54 | Yes | Repair over a T tube | No | No | None | Excellent | None |

| 3 | F | 45 | Yes | Roux-en-Y | No | No | None | Excellent | None |

| 4 | M | 76 | Yes | Repair over a T tube | Wound infection | No | None | Good | Hernia |

| 5 | M | 62 | Yes | Ligature | Liver abscess peritonitis | Drainage | None | Died | None |

| 6 | F | 65 | Yes | Ligature | Cholangitis | Roux-en-Y | None | Excellent | None |

| 7 | F | 45 | No | Ligature | Pain, fever, liver abscess | Roux-en-Y | Roux-en-Y | Good | None |

| 8 | F | 48 | No | Ligature | Pain, fever | Roux-en-Y | None | Excellent | None |

| 9 | F | 60 | No | Ligature | Temp pain | No | None | Good | None |

| 10 | F | 28 | No | None | Biliary peritonitis | Lavage, drainage | None | Closure | None |

| 11 | F | 24 | No | None | Biliary peritonitis | Lavage, drainage | Roux-en-Y | Excellent | None |

| 12 | F | 65 | No | None | Biliary peritonitis | Lavage, drainage | None | Closure | Hernia |

| 13 | F | 30 | No | None | Biliary peritonitis | Lavage, drainage | None | Closure | Ileus |

| 14 | F | 21 | No | None | Ext. fistula | No | None | Closure | None |

| 15 | F | 36 | No | None | Ext. fistula | No | None | Closure | None |

| 16 | F | 60 | No | None | Ext. fistula | No | Roux-en-Y | Excellent | None |

| 17 | M | 60 | No | None | Ext. fistula | No | Roux-en-Y | Good | None |

| 18 | F | 63 | No | None | Ext. fistula | Roux-en-Y | None | Excellent | None |

| 19 | M | 73 | No | None | Ext. fistula | Roux-en-Y | None | Excellent | None |

The second group consisted of 5 patients in whom the injured duct was ligated. Four of the patients developed cholangitis, 2 of them then also developed liver abscesses requiring drainage and biliary repair. Two patients had good long-term outcomes, the third developed a late anastomotic stricture which was then successfully resolved by further surgery, while the fourth patient developed a small temporary bile leak and pain which resolved spontaneously and required no further treatment. The fifth patient developed serious complications (a liver abscess, an abdominal wound disruption, and pneumonia) from which he finally died.

The third group was comprised of 4 patients referred from other hospitals with neglected biliary peritonitis which had lasted for several weeks. All the 4 patients underwent laparotomy, drainage and lavage. All the 4 developed an external biliary fistula through the subhepatic drain, 3 of which resolved spontaneously, and 1 of which required Roux-en-Y repair. All 4 patients had good long-term outcomes.

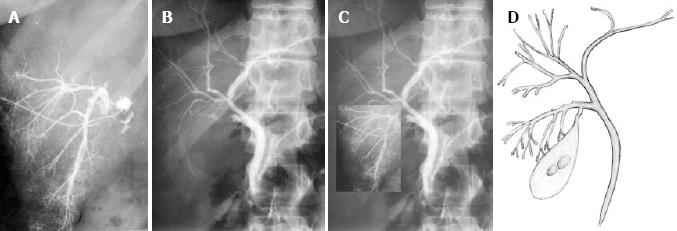

The final group consisted of 6 patients with external biliary fistulae which had lasted for between 2 and 8 wk, also referred from other hospitals. Two patients, both with an 8 wk history of a fistula, underwent immediate Roux-en-Y repair. Two other patients also underwent a Roux-en-Y repair, as their fistulae showed no signs of spontaneous closure (Figure 5). The remaining 2 patients had spontaneous closure of their biliary fistulae and required no further treatment (Figure 6).

Thus 12 (63%) patients in this series underwent some form of repair, 3 over T-tube and 9 with Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Repair was not necessary in 6 (32%) patients. 5 of the 10 patients with biliary fistula formation required Roux-en-Y repair, while 5 had spontaneous resolution. One patient (5%) who had duct ligation died.

No single method of treatment for isolated segmental, sectoral and right hepatic bile duct injuries is universally accepted. Some authors believe that due to the uncertain outcomes and potentially harmful complications of reconstructive surgery, simple ligation of injured ducts is the treatment of choice. This is felt to be the case irrespective of the size of the injured duct[2], as unobstructed drainage of up to 50% of an otherwise normal liver, through either the right or left unaffected ducts, is adequate to restore normal liver function; even with the obstructed lobe remaining in situ[34]. The non-draining lobe of the liver would then undergo progressive asymptomatic atrophy, and not require further treatment; so long as it was completely obstructed and free from infection, and that there was normal biliary flow from the residual 50% of the liver[3–5]. Although the incidence of “free communication” between the two main hepatic ductal systems above the hilum has been reported in up to 50% of patients[6], there is no evidence that the bile from an obstructed ductal system drains through the other unobstructed ducts. Other authors believe that wherever possible isolated segmental, sectoral and right hepatic bile duct injuries should be immediately repaired if recognized, in order to restore normal anatomy and function[7–9].

We favour a primary repair whenever an injury is recognized at original surgery. An end-to-end anastomosis over a tiny T-tube inserted in the common bile duct can be performed if the duct is of a reasonable size (at least 4 mm). There must be no loss of duct tissue, ductal tears or thermal injury, and the repair must be technically perfect using interrupted 5/0 slow-absorbable sutures. We believe that the end-to-end anastomosis is not indicated in injuries close to the common bile duct as any eventual stricture of the anastomosis may cause a stricture of the main bile duct. A Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy can be performed in other situations and where the remaining duct is large enough to accommodate sutures.

Patients with isolated segmental, sectoral and right hepatic bile duct injury have also been successfully treated by nonsurgical methods such as endoscopic and/or percutaneous drainage and stenting[10]. In some rare cases with high hepatic injuries segmental liver resection has even been performed in order to avoid long-term transhepatic stenting and its complications such as cholangitis and late stricture formation[11].

Although surgeons have different approaches to the treatment of isolated segmental, sectoral and right hepatic bile duct injury recognized during or soon after the original surgery, there is no major disagreement in the treatment of cases with infection, biliary peritonitis and biliary fistula. Infection is treated stepwise, initially with antibiotics and percutaneous biliary drainage where possible, and if required with a Roux-en-Y repair[5] or even with hepatic resection of the infected parenchyma and ducts[3]. Biliary peritonitis requires drainage and lavage, previously by laparotomy and now more commonly by laparoscopy, in order to prevent abdominal abscesses[12]. Biliary fistulae are treated conservatively. If they fail to resolve spontaneously then a biliary repair with a Roux-en-Y may be necessary[13].

Thus in conclusion, a primary repair, where possible, is a reasonable solution for isolated segmental, sectoral and right hepatic bile duct injury recognized during the original surgery; the larger the duct the greater need for primary repair. A patient with a ligated duct may develop an infection, and so should be closely followed up for several weeks. Infected ducts require further surgery and usually a Roux-en-Y repair. In the past, patients with biliary peritonitis were treated with open laparotomy, drainage and lavage of the abdominal cavity. Nowadays, lavage and drainage can be successfully carried out laparoscopically or even percutaneously. Biliary fistulae should be followed for several weeks as there is a 50% chance of spontaneous closure. In cases where the biliary fistula does not close within 6 to 8 wk, the patient should probably undergo a Roux-en-Y anastomosis without further delay.

I would very much like to thank Dr. Henry Dushan for his critical review and assistance in the writing of this paper in English.

| 1. | Johnston GW. Iatrogenic bile duct stricture: an avoidable surgical hazard? Br J Surg. 1986;73:245-247. |

| 2. | Hadjis NS, Blumgart LH. Injury to segmental bile ducts. A reappraisal. Arch Surg. 1988;123:351-353. |

| 3. | Longmire WP Jr, Tompkins RK. Lesions of the segmental and lobar hepatic ducts. Ann Surg. 1975;182:478-495. |

| 4. | Morrison CP, Wemyss-Holden SA, Maddern GJ. Successful management of iatrogenic bile duct injury by laparoscopic ligation. HPB. 2003;5:54-57. |

| 5. | Lillemoe KD, Petrofski JA, Choti MA, Venbrux AC, Cameron JL. Isolated right segmental hepatic duct injury: a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:168-177. |

| 6. | Baer HU, Rhyner M, Stain SC, Glauser PW, Dennison AR, Maddern GJ, Blumgart LH. The effect of communication between the right and left liver on the outcome of surgical drainage for jaundice due to malignant obstruction at the hilus of the liver. HPB Surg. 1994;8:27-31. |

| 7. | Knight M. Abnormalities of the gallbladder, bile ducts and arteries. Surgery of the gallbladder and bile ducts. 2nd ed. Butterworth: London 1981; 97-116. |

| 9. | Thompson RW, Schuler JG. Bile peritonitis from a cholecystohepatic bile ductule: an unusual complication of cholecystectomy. Surgery. 1986;99:511-513. |

| 10. | Perini RF, Uflacker R, Cunningham JT, Selby JB, Adams D. Isolated right segmental hepatic duct injury following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2005;28:185-195. |

| 11. | Lichtenstein S, Moorman DW, Malatesta JQ, Martin MF. The role of hepatic resection in the management of bile duct injuries following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am Surg. 2000;66:372-376; discussion 377. |

| 12. | Colovic R, Barisic G, Markovic V. [Long-term results of treatment of injuries of the sectoral and segmental bile ducts]. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2003;131:314-318. |

| 13. | Czerniak A, Thompson JN, Soreide O, Benjamin IS, Blumgart LH. The management of fistulas of the biliary tract after injury to the bile duct during cholecystectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1988;167:33-38. |