INTRODUCTION

Benign disorders such as primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), IgG4-related autoimmune pancreatitis, eosinophilic cholangitis, intraductal stone disease, surgical or blunt abdominal trauma, intra-arterial chemotherapy, and portal biliopathy can present with obstructive jaundice. Eosinophilic cholangiopathy is also one of the causes of sclerosing cholangitis[1–5]. The literature contains only about 40 case reports on eosinophilic cholangiopathy[4–6], and therefore, little attention has been paid to this condition. The disease is characterized by a dense transmural eosinophilic infiltration of the biliary tract. It is highly responsive to oral steroid therapy[4–6]. Surgery, including bile duct resection, is unnecessary if a diagnosis of eosinophilic cholangiopathy is made; therefore, a detailed histopathological examination of this disease has not yet been performed.

Sclerosing cholangitis from the above-mentioned etiology is sometimes difficult to differentiate from PSC. PSC patients in Japan have a higher incidence of eosinophilia, a less frequent association with inflammatory bowel disease, and a relatively frequent association with chronic pancreatitis, compared with those in Western countries[78]. Establishment of the concept of IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis accompanying autoimmune pancreatitis has resulted in solutions for the different clinical characters of PSC between Western countries and Japan, except for the higher incidence of eosinophilia in Japan[910].

We present a patient with sclerosing cholangitis and eosinophilic cholecystitis mimicking lower bile duct carcinoma, who underwent pancreatoduodenectomy and liver biopsy. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of eosinophilic cholangiopathy in which all layers of the bile duct wall and liver were histopathologically examined. This case was suggestive of an etiology of bile duct obstruction of eosinophilic cholangitis and PSC with eosinophilia.

CASE REPORT

A 46-year-old Japanese man with jaundice was admitted to our hospital. Ten months earlier, he had developed liver dysfunction with jaundice, which improved by conservative therapy. He had repeated episodes of urticaria from the age of 40 years. Physical examination disclosed no abnormalities except for scleral icterus and mild tenderness in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. Liver function test results at admission were as follows: aspartate aminotransferase (AST), 37 U/L; alanine aminotransferase (ALT), 36 U/L; alkaline phosphatase (ALP), 695 U/L; γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT), 179 U/L; total bilirubin, 12.3 mg/mL. Total white blood cell count was 3900, with a differential cell count of 59% neutrophils (normal range, 40%-69%), 3% eosinophils (1%-8%), and 31% lymphocytes (21%-49%). Hepatitis virus screening was negative and no tumor markers were elevated. Computed tomography (CT) revealed dilatation of both the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts. Diffuse thickening of the extrahepatic bile duct wall and thickening of the gallbladder wall were identified on CT (Figure 1). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) showed an obstruction of the lower bile duct (Figure 2). Endoscopic naso-biliary drainage was performed. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed no abnormal findings other than atrophic gastritis. Pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy and wedge liver biopsy were performed under the diagnosis of lower bile duct carcinoma. After the operation, minor leakage of pancreatojejunostomy developed, and conservative treatment was successful. The patient is alive without any symptoms 6 years and 6 mo after the operation at the time of writing.

Figure 1 CT demonstrating dilatation of both the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts, diffuse thickening of the wall of the extrahepatic bile duct (arrow), and thickening of the gallbladder wall (arrowhead).

Figure 2 ERC showing an obstruction of the lower bile duct (arrow).

In the resected specimen, the bile duct was slightly thickened and there was a narrow stenotic segment at the lower edge of the common bile duct. There was neither elevated lesion nor ulceration in the epithelium of the bile duct. The gallbladder was 11 × 6 cm with thickened wall, but had neither elevated lesion nor ulceration in the epithelium.

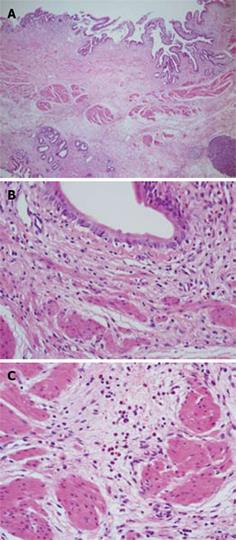

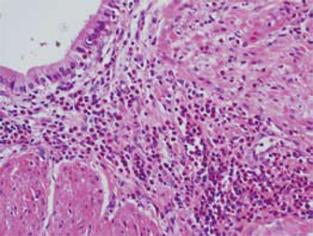

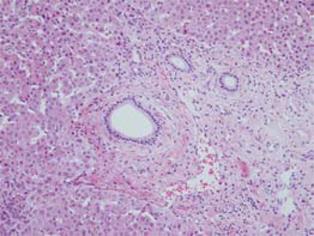

On histopathological examination, conspicuous fibrosis was seen diffusely in the bile duct wall (Figure 3A). Mild inflammatory cell infiltration, mainly composed of lymphocytes and plasma cells, was seen. Eosinophilic infiltration was very mild, and in some areas eosinophilic leukocytes were not detected (Figure 3B). Accordingly, this case was not diagnosed as definite eosinophilic cholangitis. However, careful observation revealed some areas with scattered eosinophilic leukocytes (Figure 3C). In the gallbladder wall, marked eosinophilic infiltration was seen (Figure 4), as well as scattered lymphocytes and plasma cell infiltration. Thickened fibromuscular layer and slight fibrosis in the subserosal layer were present. Hyperplastic change without atypia was identified in the gallbladder epithelium. There was no evidence of malignancy in either the bile duct or gallbladder. IgG4 immunostaining revealed hardly any positive plasma cells in the bile duct and gallbladder wall. Liver biopsy revealed mild portal fibrosis and concentric layers of fibrotic tissue surrounding the bile duct (Figure 5). This case was then definitively diagnosed as eosinophilic cholecystitis with sclerosing cholangitis of unknown etiology. However, focal infiltration of eosinophilic leukocytes in the bile duct wall suggested the possibility of eosinophilic cholangitis with very mild eosinophilic infiltration.

Figure 3 Histological examination of the bile duct wall.

A: Conspicuous fibrosis was seen diffusely in the bile duct wall; B: Eosinophilic infiltration was very mild, and in some areas eosinophilic leukocytes were not seen; C: There were some areas with scattered eosinophilic leukocytes.

Figure 4 Histological examination showing marked eosinophilic infiltration in the gallbladder wall.

Figure 5 Liver biopsy showing mild portal fibrosis and concentric layers of fibrotic tissue surrounding the bile duct.

DISCUSSION

Sclerosing cholangitis is classified into two entities: PSC and secondary sclerosing cholangitis (SSC)[211]. SCC is morphologically similar to PSC but it originates from a known pathological process. SSC includes IgG4-related autoimmune pancreatitis, eosinophilic cholangitis, intraductal stone disease, surgical or blunt abdominal trauma, intra-arterial chemotherapy, portal biliopathy, hepatic inflammatory pseudotumor, and AIDS-related cholangiopathy[211].

In the present case, a certain diagnosis of eosino-philic cholecystitis or cholangiopathy could be made. Eosinophilic cholangiopathy is a rare benign cause of biliary obstruction[13–6]. It is characterized by dense transmural eosinophilic infiltration of the biliary tract. When eosinophilic infiltration is localized in the bile duct, it is termed eosinophilic cholangitis. When it involves the gallbladder, it is called eosinophilic cholecystitis. Eosinophilic cholangiopathy is the term used to describe changes in either or both of them[512]. The cause of this disease is unknown. In more than half of the reported cases, eosinophilic infiltration is seen not only in the biliary tract but also in other organs, including the stomach, colon, pancreas, liver, and kidney[4–613]. Eosinophilic cholangiopathy is thought to be part of a spectrum of diseases caused by eosinophilic infiltration of tissues and organs with or without peripheral eosinophilia. The recognition of peripheral eosinophilia (especially in the absence of leukocytosis) is important. However, peripheral eosinophilia was present in only about half of the reported cases[6]. Some authors reported that patients with eosinophilic cholangitis had been treated successfully with oral corticosteroids[4–6]. In fact, a few cases of eosinophilic cholangitis have been resolved within 3 wk, even without steroids[13].

Bile duct wall thickening is a characteristic finding of eosinophilic cholangitis on imaging modalities[4614]. Thickening of the wall of the biliary tree usually, but not always, leads to biliary obstruction[6]. In most cases, bile duct stricture is located diffusely from the hepatic hilum to the intrahepatic biliary tree, but there is a report describing lower bile duct stricture in a patient with eosinophilic cholangitis[5]. The cause of thickening and obstruction of the biliary tract in patients with eosinophilic cholangitis is unclear because no resected case has been reported. Ours is believed to be the first reported case of eosinophilic cholangiopathy in which all layers of the biliary tract wall were histopathologically examined. The most plausible cause of sclerosing cholangitis in our case was eosinophilic cholangiopathy, based on the fact that there was marked eosinophilic infiltration in the gallbladder wall and scattered eosinophilic infiltration in the bile duct wall. Close examination of all layers of the bile duct wall enabled us to find focal infiltration of eosinophilic leukocytes.

Experimental studies have demonstrated the close relationship between eosinophilic infiltration and fibrosis. It is considered that eosinophils play an important role in the fibrotic conditions of different etiopathology, including endomyocardial fibrosis, scleroderma and scleroderma like-conditions, idiopathic pulmonary and retroperitoneal fibrosis, asbestos-induced lung fibrosis, wound repair, and tissue remodeling[1516]. It has been demonstrated that transforming growth factor-β, a cytokine known for its ability to promote fibrosis, is produced by human eosinophils from patients with blood eosinophilia[1617]. Ten months before admission, our case had developed liver dysfunction with jaundice, which was diagnosed by observation only. This means that eosinophilic cholangitis might have existed 10 mo earlier. This led to speculation that the etiology of our sclerosing cholangitis case was consequent fibrosis from previous eosinophilic infiltration in the bile duct wall. In this regard, bile duct thickening in patients with eosinophilic cholangitis might correspond to fibrosis.

Peripheral eosinophilia was observed in 27% of PSC in Japan, although reports of eosinophilia in PSC in other countries are rare[818]. Based on the liver biopsy findings and cholangiography, the present case was not diagnosed as PSC. However, in some cases, eosinophilic cholangiopathy causes sclerosing cholangitis, which closely resembles PSC. In patients with eosinophilic cholangitis without peripheral eosinophilia, a differential diagnosis from PSC is difficult without bile duct biopsy. Eosinophilic cholangiopathy might also be confused with PSC with eosinophilia. There is a case report of PSC associated with increased peripheral eosinophilitis and serum IgE[19]. In that report, a 20-year-old Japanese man received oral corticosteroid therapy and improved in a few days. The possibility that he had eosinophilic cholangitis is high from the viewpoint of his clinical course, although a definite diagnosis could not be made because histopathological material was unavailable.

In summary, we have reported a case of SSC with eosinophilic cholecystitis. Close examination of the biliary tract of the resected specimen and a literature review suggested that bile duct wall thickening in patients with eosinophilic cholangitis may be due to fibrosis of the bile duct wall and that eosinophilic cholangiopathy might be confused with PSC with eosinophilia. Confirmation will depend on further investigations.