CASE REPORT

A 37-year-old, gravida 3, para 3 woman was admitted during wk 36 of gestation to our obstetrics department for further evaluation. The patient had a history of preprandial, crampy, epigastric pain and diarrhea for several years. Her father died of colorectal cancer in his late fifties and her mother had breast cancer. However, neither Amsterdam II nor Bethesda criteria for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) were met by the family[6].

Years previously, the symptoms had been attributed to lactose intolerance. A prescribed diet did not provide any relief, but gastroscopy performed 2 years prior to definitive diagnosis of gastric cancer was normal. Infection with H pylori was diagnosed by using the 13C-urea breath test, and its eradication led to amelioration of her symptoms. The complaints recurred less than a year later, with the cardinal symptom of preprandial epigastric pain.

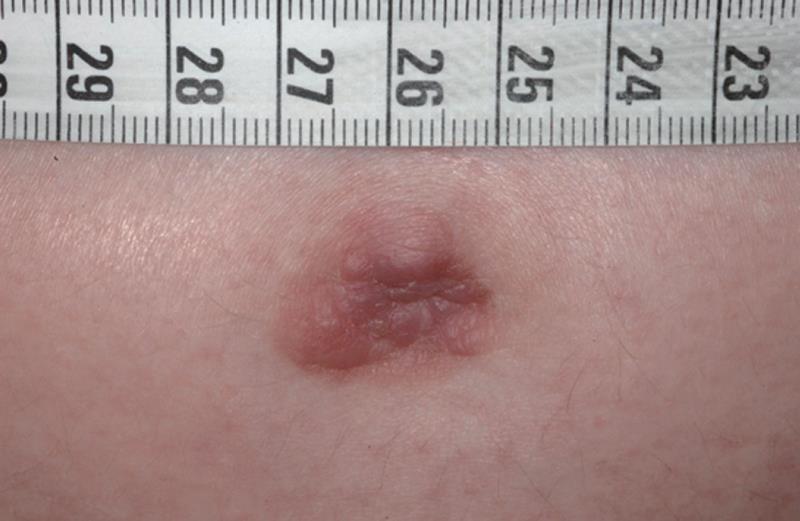

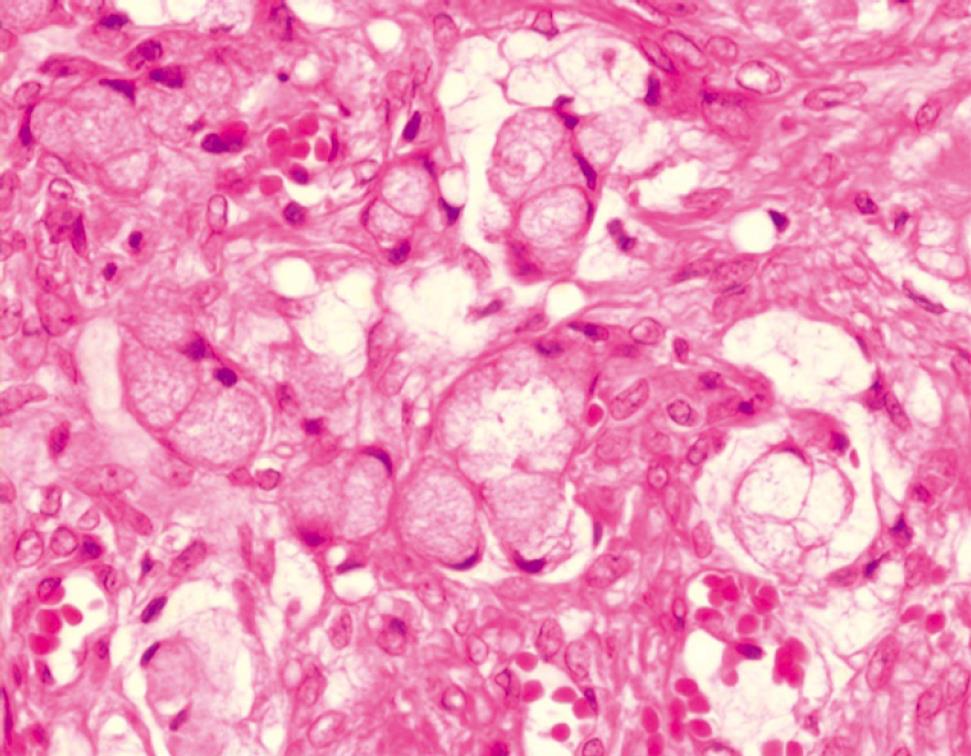

The patient noticed at this time a red, pressure-sensitive lesion with a diameter of 2 cm on her umbilicus. Her general practitioner did not perform any additional investigation of the lesion because he deemed it as harmless. Two months later, her fourth pregnancy was achieved. Melena and intermittent rectal bleeding occurred in wk 10 of gestation, but the symptoms were attributed to pregnancy-related hemorrhoids. Since the umbilical lesion evolved into a nodule with a bumpy irregular surface (Figure 1), she was referred to the department of dermatology. A biopsy was performed at wk 34 of gestation; histological examination revealed a diffuse, undifferentiated, growing carcinoma of unknown origin (Figure 2), and some cells containing cytoplasmatic mucin. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule was confirmed as the first presenting sign of cancer during pregnancy.

Figure 1 Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule.

Figure 2 Histology of Sister Mary Joseph's nodule with diffuse, undifferentiated growing carcinoma cells, some containing cytoplasmatic mucin.

Physical examination upon admission was unremarkable, except for normal signs of pregnancy and pallor. The patient was slightly anemic at the time of presentation, with a hemoglobin level of 7.3 mmol/L and a hematocrit of 34%. Other laboratory data, which included liver function tests and a basic chemistry panel, were within normal limits. Tumor marker assessment revealed elevated serum concentrations for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA, 293.8 U/mL, normal range < 39.0 U/mL) and cancer antigen-125 (CA-125, 39.8 U/mL, normal range < 35.0 U/mL). Other tumor markers stood within normal range. On ultrasound scan and color duplex sonography, the fetus was developing well with no pathological findings.

The patient was referred to our gastroenterology department where she underwent gastroscopy. A rough ulcer, about 3 cm in diameter, originated from the angular notch. Biopsy revealed a poorly differentiated gastric adenocarcinoma with signet ring cells. Diagnostic imaging (abdominal ultrasonography, thoracic CT and abdominal MRI) showed no clear evidence of metastases. Breast and thyroid sonography showed no abnormalities.

The patient delivered by cesarean section a healthy, 3.2 kg female (Apgar score, 10/10/10). Cesarean section was followed by abdominal and pelvic exploration, which revealed bilateral ovarian tumors (Krukenberg tumors), metastatic spread to the lymph nodes throughout the peritoneal cavity, and tumor infiltration of the spleen and transverse colon. Extensive carcinomatosis of the parietal peritoneum and of the surfaces of the gall bladder and small intestine was present. Total gastrectomy, splenectomy, cholecystectomy, extended right-sided hemicolectomy, bilateral adnexectomy and excision of the umbilicus were performed followed by reconstruction by Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy. All the visible tumor tissue was removed. Histological examination showed a poorly differentiated gastric adenocarcinoma with signet ring cells, of mixed type according to Laurén’s classification, which was identified in large proportions of the entire stomach, and not only located in the previously described ulcer. The pathologist confirmed stage III disease because of peritoneal carcinomatosis, and interpreted the umbilical lesion as metastatic spread and not as continuous skin infiltration by the tumor. The placenta and umbilical cord, however, were free of metastases. Palliative chemotherapy began immediately postpartum. The further postoperative course was complicated by a leak at the blind end of the jejunal loop of the esophagojejunostomy, and a subphrenic abscess with peritonitis. Surgical reintervention was carried out and chemotherapy stopped temporarily. At present, the patient is recovering from surgery and the chemotherapy has been resumed. The baby is doing well.

DISCUSSION

An extended review of literature revealed no previously reported cases of umbilical metastasis as the first presenting sign of gastric cancer during pregnancy.

The term “Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule” was coined by Sir Hamilton Bailey in his book, Physical Signs in Clinical Surgery, in honor of Sister Mary Joseph, Dr. William Mayo’s surgical assistant in the early days of the Mayo Clinic. Sister Mary Joseph identified the relationship between umbilical nodules and advanced intra-abdominal malignancy[78]. Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule is an umbilical metastasis most commonly found in advanced-stage adenocarcinomas of the upper gastrointestinal tract and ovary. Less commonly, the nodule may be a metastatic lesion from colon or pancreatic cancer[910]. The presence of an umbilical metastasis indicates a poor prognosis and is a sign of advanced malignant disease. The survival of these patients has been reported to range from 2 to 11 mo from the time of initial diagnosis[10–13].

Gastric cancer primarily occurs in patients over 50 years of age. The described proportion of young patients with gastric cancer varies from 2% to 15% depending on the age defined as young[1415]. Female patients have a relative dominance in this group and the incidence of gastric cancer is higher in women over the age of 30 years. The frequency of pregnancy has been increasing in these women and this may lead to a higher coincidence of pregnancy and gastric cancer[2]. Pregnancy-associated gastric cancer is currently attributed to 0.1% of all cases[16]. There is an increased risk of diffuse and scirrhous type carcinomas in this group of patients[41718].

Common presenting signs and symptoms of gastric cancer include dyspepsia, epigastric pain, early satiety, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, anemia, dysphagia, weight loss and melena. Except for weight loss and melena, all of these symptoms are common in pregnancy. Weight loss can be caused by hyperemesis gravidarum or compensated and masked by the weight gain in pregnancy, and melena may be initially attributed to pregnancy-related hemorrhoids.

In our case, the tumor was advanced at the time of diagnosis. We can only speculate that the delay between the first symptoms and diagnosis might have been several years, possibly due to multiple pregnancies concealing the symptoms during that time. To diagnose diffuse-type gastric cancer is sometimes difficult, if there is no typical lesion and an adequate number of biopsies is taken during gastroscopy. In our case, the cancer was spread throughout the stomach and was not only located in the ulcer region. An adequate number of biopsies taken during previous endoscopies would have made an earlier diagnosis possible. Marconi et al have reported a mean delay, from first symptoms to final diagnosis, of 29.3 ± 9.9 wk in young patients without alarm symptoms[19]. The initial diagnosis of gastric carcinoma is often delayed because up to 80% of patients are asymptomatic during the early stages of gastric cancer[20]. When symptoms are present, they can be misinterpreted as simply pregnancy-related. Hormonal stimulation and pregnancy in young women may accelerate the growth of gastric cancer[321]. Therefore, we tested for estrogen and progesterone receptors in our patient’s tumor and the results were negative. Our patient had consecutive pregnancies with continuous, worsening symptoms. The presence of the umbilical lesion 2 mo before the latest pregnancy strongly suggests that the disease was already at an advanced stage at that time. Gastric cancer should be included, therefore, in the differential diagnosis of unusual or prolonged gastrointestinal symptoms after the first trimester of pregnancy, and in women who have recently been pregnant[1521]. Coexistent risk factors such as positive family history should trigger immediate further investigation through gastrointestinal endoscopy, which is not contraindicated during pregnancy.

The unique presenting sign of Sister Mary Joseph’s nodule indicates an advanced malignant disease with poor prognosis for the mother, but not for the baby. Such nodules might be misinterpreted as eczematous lesions. Based on our case, it is evident that a skin lesion in the umbilical area might indicate malignant disease, and biopsy should be considered if short-term (1-2 wk) local treatment is not successful.