Published online Dec 7, 2008. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.7005

Revised: November 11, 2007

Accepted: November 18, 2007

Published online: December 7, 2008

Systemic mastocytosis (SM) is a rare disease with abnormal proliferation and infiltration of mast cells in the skin, bone marrow, and viscera including the mucosal surfaces of the digestive tract. Gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms occur in 14%-85% of patients with systemic mastocytosis. The GI symptoms may be as frequent as the better known pruritus, urticaria pigmentosa, and flushing. In fact most recent studies show that the GI symptoms are especially important clinically due to the severity and chronicity of the effects that they produce. GI symptoms may include abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and bloating. A case of predominantly GI systemic mastocytosis with unique endoscopic images and pathologic confirmation is herein presented, as well as a current review of the GI manifestations of this disease including endoscopic appearances. Issues such as treatment and prognosis will not be discussed for the purposes of this paper.

- Citation: Lee JK, Whittaker SJ, Enns RA, Zetler P. Gastrointestinal manifestations of systemic mastocytosis. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14(45): 7005-7008

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v14/i45/7005.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.7005

| Esophageal | Gastric and Duodenal | Small Intestine | Colon and Rectum |

| Esophagitis | Peptic ulcers | Thickened jejunal folds with edema | Nodular lesions |

| Esophageal stricture | Thickened gastric or duodenal folds | Dilated small bowel | Urticarial lesions in the rectum |

| Varices | Nodular mucosal lesions | Multiple polypoid lesions | |

| Urticarial lesions | Diffuse intestinal telangiectasias |

Systemic mastocytosis (SM) is characterized by abnormal growth and accumulation of mast cells in various organs[1]. SM represents a heterogeneous group of disorders with varying frequencies of GI disease[2]. Different studies report a wide array of GI involvement with a range from 14%-85% and more recent studies suggest that it comes as a close second commonest symptom next only to pruritus[2,3]. The differences in reported GI symptoms are thought to reflect the heterogeneous population of SM studied, methodology of studies, and the differences in the definition of mastocytosis[2]. Indeed the involvement of the GI tract has been shown to vary with the Metcalfe type of SM[4,5]. It must be stressed that while most patients have pruritus or urtication, these symptoms generally cause less significant discomfort for patients than the GI symptoms which are more distressing chronic complaints[6,7].

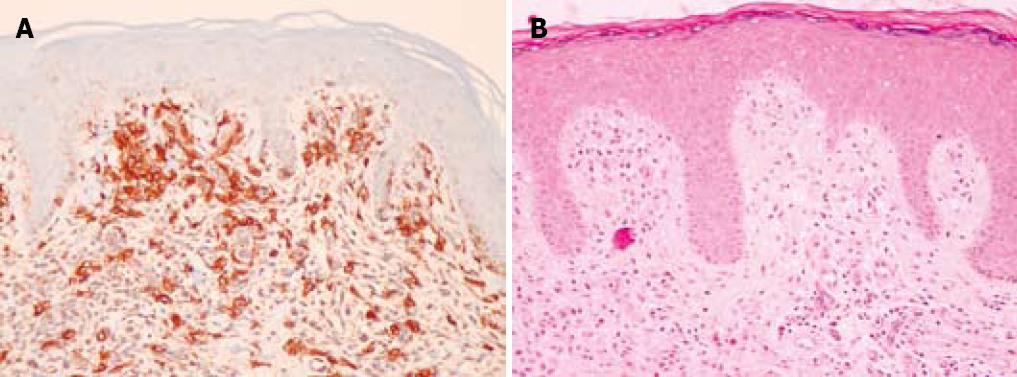

A 75-year-old man with a history of colonic polyps, hypertension, childhood tonsillectomy, and a remote smoking history presented with a complaint of “excessive mucus in the throat” for the past several years. The patient had a sensation of a “sore throat” for years along with more frequent bowel movements and increased flatus. There were no other gastrointestinal complaints. The patient subsequently had maculopapular rashes which on biopsy showed increased numbers of dermal mast cells highlighted by c-kit (CD 117) immunoperoxidase staining consistent with that of dermal mastocytosis (Figure 1A). The haematoxylin and eosin stain (HE) is also included (Figure 1B).

When seen by the gastroenterologist, the patient had no lymphadenopathy in the head and neck region but did have tissues in the distal soft palate and pharynx appearing uniformly swollen and hyperemic. The respiratory, cardiovascular, and neurological exams were grossly normal. On abdominal exam there was no organomegaly, masses, tenderness, or inguinal lymphadenopathy. A ventral hernia was noted.

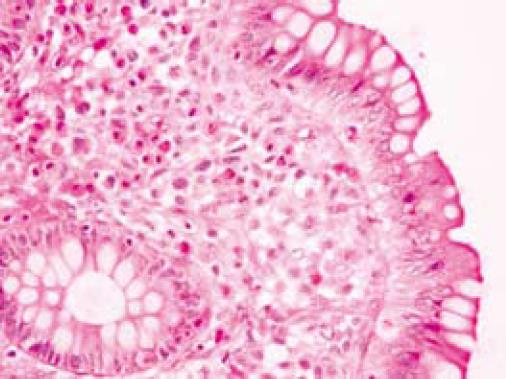

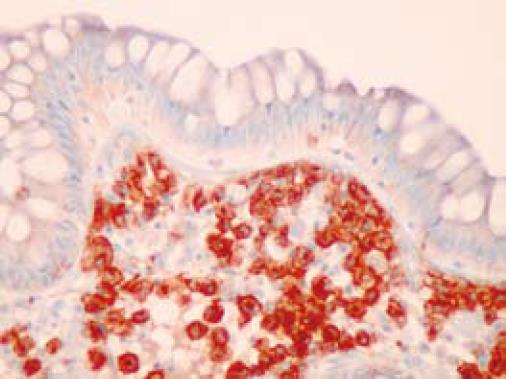

On colonoscopy a mucus type material adherent to the mucosa was present in the right colon along with a slightly raised appearance of the mucosa through areas of the transverse and right colon (Figure 2). The biopsy in these colonic regions showed an increased number of mast cells with recruited eosinophils in the lamina propria (Figure 3 HE). The mast cells are highlighted by positive c-kit staining (Figure 4).

Common GI complaints in SM include abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting[2]. It appears that the frequency of various GI symptoms is less variable than their prevalence[2]. These symptoms are thought to be secondary to mast cell mediators on the GI tract. The most common symptom is abdominal pain (mean 51%) followed by diarrhea (mean 43%) and nausea or vomiting (mean 28%)[2]. Abdominal pain can be classified into two different types corresponding to different pathology. Epigastric dyspeptic pain is associated with ulcer disease and acid hypersecretion whereas no dyspeptic pain is characterized by lower abdominal cramps[8]. Diarrhea is thought to occur due to gastric acid hypersecretion, malabsorption caused by mucosal injury and edema, and altered bowel motility[8]. Moreover, diarrhea in SM can also be caused or contributed to by tissue infiltration by mast cells[3,9]. It is however worth noting that the mast cells themselves do not secrete gastrointestinal peptides that directly alter motility[3].

A common symptom in SM is facial flushing[10]. The flushing in SM can be distinguished from the flushing seen in the rare but more prevalent carcinoid tumors in that carcinoid flushing is generally more widespread, patchy, violaceous, and evanescent, lasting only a few minutes, often occurs postprandially, and in the majority of cases not associated with hemodynamic changes[10]. Furthermore, the response to long acting somatostatin analogue octreotide, the specific pattern of mediator excretion, and aggravation of the flushing by epinephrine in the carcinoid case can assist in the differentiation[10,11]. In SM, the flushing tends to be more bright red, pruritic, and burning, and may be accompanied simultaneously by other symptoms of systemic mast cell degranulation including GI symptoms[10,12].

Other symptoms may also occur as a result of GI bleeding and peptic ulcer disease[2,3]. It is estimated that GI bleeding occurs in 11% of SM[2]. Contrary to previously reports it is estimated that peptic ulcer disease is an under diagnosed phenomena[2]. Indeed in a more recent prospective study within which nine patients had upper GI endoscopy, four of the nine patients had peptic ulcer disease[3]. Interestingly, hypersecretion of gastric acid is not consistently related to the level of serum histamine levels measured[3]. It may however be possible that a relationship between tissue concentration of histamine and GI manifestations may exist[3]. It is unclear what triggers the vasoactive mediators from mast cells but certain medications such as NSAIDS, opiate analgesics, procaine, and penicillin may be potential triggers[13].

Rarely, esophageal complaints in SM are made and include symptoms due to esophagitis and in some reports variceal bleeding secondary to portal hypertension that may develop in SM[14].

Signs of GI SM include steatorrhea, malabsorption, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly[2] and sometimes ascites secondary to portal hypertension. Steatorrhea can be measured by 72-h fecal fat excretion test, D-xylose tolerance test, and Shilling test. In SM steatorrhea is associated in 5%-67% of patients[7,15,16]. Hepatomegaly was found in 41%-72% of patients[12,17]. Mast cells are known to infiltrate the liver diffusely with or without portal fibrosis and rarely cirrhosis in 4% of patients[12]. Portal hypertension is also reported in association with SM[18,19] and is ascribed to pre- and post-sinusoidal block secondary to mast cell infiltration and or fibrosis[18]. Splenomegaly attributable to SM is thought to be due to mast cell infiltration that may accompany hepatomegaly[20,21]. Marked splenomegaly was found to be more common in aggressive SM[22]. Since SM is a rare entity a low clinical suspicion is required and usually the diagnosis is made on biopsy[10].

Case reports highlight some of the more unusual pathology. One such is SM and giant gastroduodenal ulcers associated with telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans which is thought to represent a cutaneous form of mastocytosis[8]. Rarely aggressive SM can be complicated by protein-losing enteropathy[23]. Other reports include initial misdiagnosis as SM can mimic inflammatory bowel disease[9,24] and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome[24].

Small intestinal pathology may reveal dilated loops of bowel and thickened, edematous or scalloped folds[6,25]. In the colon, urticarial lesions, diverticulitis, polypoid lesions, and diffuse intestinal telangiectasia may be seen (Figure 3)[25,26].

Diagnosis of SM is based on identification of neoplastic mast cells by morphologic, immunophenotypic, and/or genetic criteria in various organs. Specifics of the World Health Organization criteria for the diagnosis of SM based on a paper by Valent et al[27] will not be discussed. Currently there is no consensus GI biopsy criteria.

Needless to say, patients with obvious dermatological findings are diagnosed by clinicians more quickly as having SM. Unfortunately, patients lacking skin manifestations of SM have a delayed diagnosis even though they often have more aggressive disease, impaired liver function, ascites, malabsorption, and splenomegaly[28].

Interestingly our endoscopic images (Figure 2) from the colonic involvement look markedly different from previously published images by Scolapio et al[25]. In the pictures provided in this paper, the appearance of SM in the colon would be described as small mucosal nodules with focal areas of edema, urticarial, granular, and multiple purple-pigmented lesions. To date these are the first endoscopic images that contain all of these features although these findings have been reported in isolation or in pairs[25,29,30].

An earlier review by Jensen in 2000 has reported the following endoscopic findings which are displayed in a table[2]. (Table 1 adapted from Jensen[2]).

This report describes an interesting case of a rare cause of chronic diarrhea. It is important to consider this diagnosis in the work up of intractable diarrhea. The distinct endoscopic appearance of this disorder may at times be seen and it is recommended that this information be communicated to the pathologist responsible so that special stains may be performed, allowing the information to perhaps contribute to the diagnosis of SM. It is important to identify potential triggers for GI symptoms of SM as well as to initiate symptomatic treatments. Presently there is no cure for SM and it is recommended that cytoreductive therapy and ensuing management be planned carefully with expert hematologists and hematopathologists.

| 1. | Patnaik MM, Rindos M, Kouides PA, Tefferi A, Pardanani A. Systemic mastocytosis: a concise clinical and laboratory review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:784-791. |

| 2. | Jensen RT. Gastrointestinal abnormalities and involvement in systemic mastocytosis. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2000;14:579-623. |

| 3. | Cherner JA, Jensen RT, Dubois A, O’Dorisio TM, Gardner JD, Metcalfe DD. Gastrointestinal dysfunction in systemic mastocytosis. A prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:657-667. |

| 4. | Metcalfe DD. Mastocytosis. Novartis Found Symp. 2005;271:232-42; discussion 242-249. |

| 5. | Metcalfe DD. Classification and diagnosis of mastocytosis: current status. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:2S-4S. |

| 6. | Tebbe B, Stavropoulos PG, Krasagakis K, Orfanos CE. Cutaneous mastocytosis in adults. evaluation of 14 patients with respect to systemic disease manifestations. Dermatology. 1998;197:101-108. |

| 7. | Horan RF, Austen KF. Systemic mastocytosis: retrospective review of a decade’s clinical experience at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:5S-13S. |

| 8. | Arguedas MR, Ferrante D. Systemic mastocytosis and giant gastroduodenal ulcer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:530-533. |

| 9. | Bedeir A, Jukic DM, Wang L, Mullady DK, Regueiro M, Krasinskas AM. Systemic mastocytosis mimicking inflammatory bowel disease: A case report and discussion of gastrointestinal pathology in systemic mastocytosis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1478-1482. |

| 10. | Butterfield JH. Systemic mastocytosis: clinical manife-stations and differential diagnosis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2006;26:487-513. |

| 11. | Adamson AR, Grahame-Smith DG, Peart WS, Starr M. Pharmacological blockade of carcinoid flushing provoked by catecholamines and alcohol. Lancet. 1969;2:293-297. |

| 12. | Horny HP, Kaiserling E, Campbell M, Parwaresch MR, Lennert K. Liver findings in generalized mastocytosis. A clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1989;63:532-538. |

| 14. | Silvain C, Levillain P, Mouton P, Carretier M, Babin P, Beauchant M. [Systemic mastocytosis disclosed by rupture of esophageal varices]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1989;13:834-837. |

| 15. | Soter NA, Austen KF, Wasserman SI. Oral disodium cromoglycate in the treatment of systemic mastocytosis. N Engl J Med. 1979;301:465-469. |

| 16. | Barriere H, Dreno B, Pecquet C, Le Bodic MF, Bolze JL. [Systemic mastocytosis and intestinal malabsorption]. Sem Hop. 1983;59:2925-2931. |

| 17. | Travis WD, Li CY, Bergstralh EJ, Yam LT, Swee RG. Systemic mast cell disease. Analysis of 58 cases and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 1988;67:345-368. |

| 18. | Capron JP, Lebrec D, Degott C, Chivrac D, Coevoet B, Delobel J. Portal hypertension in systemic mastocytosis. Gastroenterology. 1978;74:595-597. |

| 19. | Fonga-Djimi HS, Gottrand F, Bonnevalle M, Farriaux JP. A fatal case of portal hypertension complicating systemic mastocytosis in an adolescent. Eur J Pediatr. 1995;154:819-821. |

| 20. | Travis WD, Li CY. Pathology of the lymph node and spleen in systemic mast cell disease. Mod Pathol. 1988;1:4-14. |

| 21. | Gonnella JS, Lipsey AI. Mastocytosis manifested by hepatosplenomegaly. Report of a case. N Engl J Med. 1964;271:533-535. |

| 22. | Metcalfe DD. The liver, spleen, and lymph nodes in mastocytosis. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:45S-46S. |

| 23. | Mickys U, Barakauskiene A, De Wolf-Peeters C, Geboes K, De Hertogh G. Aggressive systemic mastocytosis complicated by protein-losing enteropathy. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:693-697. |

| 24. | Blonski WC, Katzka DA, Lichtenstein GR, Metz DC. Idiopathic gastric acid hypersecretion presenting as a diarrheal disorder and mimicking both Zollinger-Ellison syndrome and Crohn‘s disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:441-444. |

| 25. | Scolapio JS, Wolfe J 3rd, Malavet P, Woodward TA. Endoscopic findings in systemic mastocytosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:608-610. |

| 26. | Miner PB Jr. The role of the mast cell in clinical gastroi-ntestinal disease with special reference to systemic masto-cytosis. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:40S-43S; discussion 43S-44S, 60S-65S. |

| 27. | Valent P, Horny HP, Escribano L, Longley BJ, Li CY, Schwartz LB, Marone G, Nunez R, Akin C, Sotlar K. Diagnostic criteria and classification of mastocytosis: a consensus proposal. Leuk Res. 2001;25:603-625. |

| 28. | Valent P, Akin C, Sperr WR, Mayerhofer M, Fodinger M, Fritsche-Polanz R, Sotlar K, Escribano L, Arock M, Horny HP. Mastocytosis: pathology, genetics, and current options for therapy. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005;46:35-48. |

| 29. | Dantzig PI. Tetany, malabsorption, and mastocytosis. Arch Intern Med. 1975;135:1514-1518. |

| 30. | Mahood JM, Harrington CI, Slater DN, Corbett CL. Forty years of diarrhoea in a patient with urticaria pigmentosa. Acta Derm Venereol. 1982;62:264-265. |

Peer reviewers: Yvette Taché, PhD, Digestive Diseases Research Center and Center for Neurovisceral Sciences and Women’s Health, Division of Digestive Diseases, Department of Medicine, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, University of California, Los Angeles and VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, 11301 Wilshire Boulevard, CURE Building 115, Room 117, Los Angeles, CA, 90073, United States; Nikolaus Gassler, Professor, Institute of Pathology, University Hospital RWTH Aachen, Pauwelsstrasse 30, 52074 Aachen, Germany

S- Editor Li JL L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Ma WH