INTRODUCTION

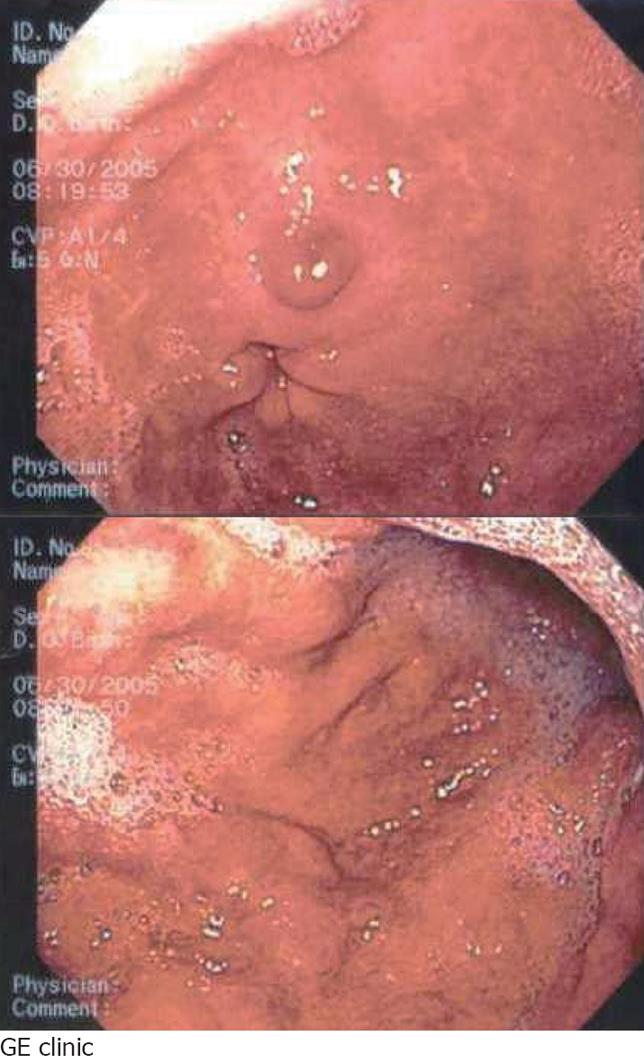

Figure 1 Endoscopic views of gastric antrum and gastric body showing non-specific erythematous and thickened mucosal folds with pre-pyloric pseudopolypoid change.

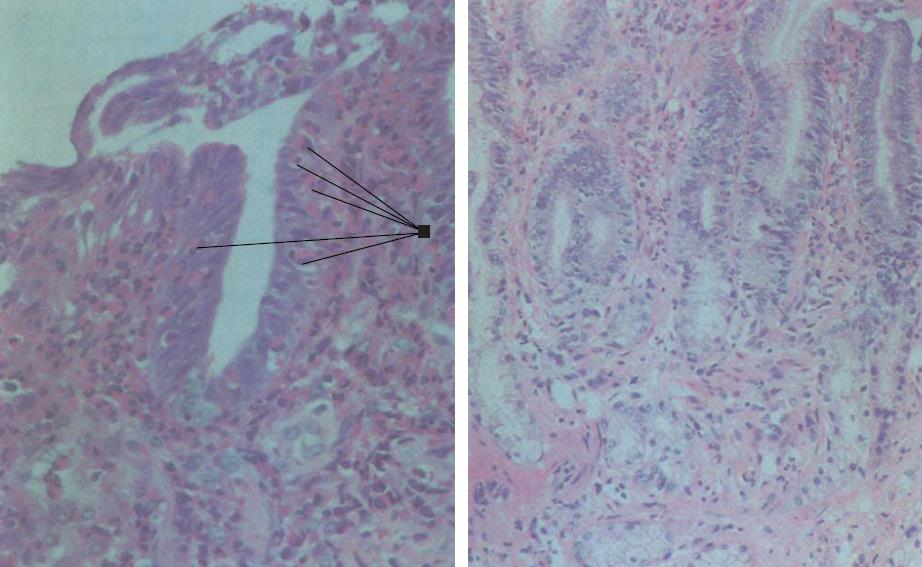

Figure 2 Photomicrographs show a formalin-fixed biopsy on the left with arrows delineating intraepithelial eosinophils along with numerous eosinophils in the lamina propria, while a Bouin’s fixed biopsy on the right from an adjacent endoscopic biopsy shows a paucity of eosinophils.

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis (EGE) is a distinct eosinophil-predominant inflammatory process in gastric or small intestinal mucosal biopsies. Although most published material has focused largely on the pediatric population, this manuscript focuses on the adult with EGE. Most often in adults, EGE is detected during endoscopic investigation for abdominal pain or diarrhea[1-4]. Although the endoscopic changes are non-specific (Figure 1), chronic or recurring symptoms are present and other causes of intestinal eosinophilia require exclusion (e.g. parasitic infections, medications)[1-4]. The mucosa of the stomach, intestine, or both may be involved most frequently. In one specific classification schema that included different forms of intestinal eosinophilic infiltration, involvement of the muscular layer or serosa was also described, but even in these, concomitant mucosal involvement was often present[5].

EGE has been considered an uncommon, even rare disorder but this may well depend on its definition as well as the method of detection. In a single clinical practice, only less than 1% of all upper endoscopic studies during an 8-year period showed changes that led to a diagnosis of EGE[6]. Biopsies are now commonly done during routine endoscopic evaluation, even if the mucosa is visually normal or if only non-specific changes are present. Finally, it is speculated that there may be some environmental factors (or allergen) in the diet or air that plays a critical role in the emergence of an eosinophil-predominant mucosal inflammatory process.

HISTOPATHOLOGICAL CRITERIA

Most often, the diagnosis of EGE is defined by histological evaluation of endoscopic biopsies. There are some potential diagnostic issues and pitfalls. First, pathologists, like endoscopists, have varying levels of expertise in mucosal biopsy interpretation. It is appreciated that there may be many “shades of grey” in the definition of EGE and the experience of the pathologist may determine disease recognition. To date, however, precise information on intra- and inter-observer error in the interpretation of biopsies in EGE is still needed. Second, eosinophils may normally be detected in the gastric and intestinal mucosa (as opposed to the normal esophagus), and only limited numbers of studies (mainly in children) have tried to quantify normal compared to abnormal numbers in health and different inflammatory disease states, e.g. ulcerative colitis[7,8]. Third, these studies are also limited, to some degree, by the inherent “patchy” nature of the eosinophilic inflammatory process in EGE since the numbers of eosinophils may differ in biopsies obtained from different sites. Finally, fixation methods may be critical in the definition of eosinophils in gastric and intestinal biopsies. For example, Bouin’s solution (often used for gastric or intestinal biopsies), can result in “bleaching” of eosinophil granules making detection much more difficult. If EGE is suspected, routine formalin fixation has been shown to provide more optimal material for routine staining (Figure 2)[9].

CLINICAL FEATURES

Prior studies have suggested that EGE is a male-predominant clinical disorder[1]. Some believe that clinical features may reflect extent, location and depth of infiltration of this eosinophilic inflammatory process within the gastrointestinal tract[1,5]. Abdominal pain and diarrhea are common. Weight loss may occur, in part related to malabsorption. Iron deficiency associated with blood loss as well as protein-losing enteropathy may also be seen. If muscular layers are involved, obstruction or, even an acute abdomen has been recorded[1-4], while serosal involvement may be associated with evidence of ascites[5]. Peripheral blood eosinophilia has been recorded in up to 70%, but this is not specific for EGE and should lead to exclusion of other disorders, specifically parasitic infections[3]. In some with EGE, increased serum IgE levels may be seen, but this is also not specific. Endoscopic evaluation might permit definition of the extent of the inflammatory process in the upper gastrointestinal tract. In rare reports[10,11], celiac disease has been linked to EGE but as completely independent disorders.

Treatment is largely aimed at resolving symptoms. Medications used in EGE are largely based on empiric observation and experience. Because of the rarity of EGE, there are no controlled treatment trials available. Steroids have been used as a traditional form of therapy to reduce the inflammatory process[1-4], however, these may cause steroid-related effects, especially because of their recurring need over prolonged periods. Other remedies have been used but their effectiveness still requires definition. These include: proton pump inhibitors[5], mast cell stabilizers[12,13], ketotifen[9,14], leukotriene antagonists[15], octreotide[16] and surgical resection of involved intestinal segments[17]. This lengthening therapeutic list might be construed as a clear reflection of the limited forms of effective therapy that are currently available.

HYPEREOSINOPHILIC SYNDROMES

The hypereosinophilic syndromes (HES) represent a heterogeneous group of rare disorders that have been defined in the past by persistent blood eosinophilia for more than 6 mo with evidence of organ involvement. The cause is unknown. HES may include a broad spectrum of disorders, including familial or genetically-based eosinophilia and more sinister neoplastic disorders, including eosinophilic leukemia[1,19]. About 25% of cases with HES, however, have eosinophilic infiltration in the gastrointestinal tract, and in some, this inflammatory process is reportedly localized only in gastric or intestinal mucosa.

The onset of HES is generally described between ages of 20 and 50 years with a male predominance[1]. Abdominal pain and diarrhea with malabsorption have been described. In comparison with those with disease localized in some other non-intestinal sites, involvement of the intestinal tract has been associated with a limited prognosis, lympho-proliferative disorders[20], and, in some, a fatal outcome[1]. Unfortunately, there may be little to distinguish EGE and HES, especially if the latter is early in the clinical course and localized to the gastric and intestinal mucosa alone. In some, steroids, immune-suppressants and even biological agents have been used[21]. Clearly, long-term clinical studies are needed to define and elucidate the natural history of EGE, a relatively unique inflammatory process, and to determine if there is a potential HES risk.

S- Editor Xiao LL L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Yin DH