INTRODUCTION

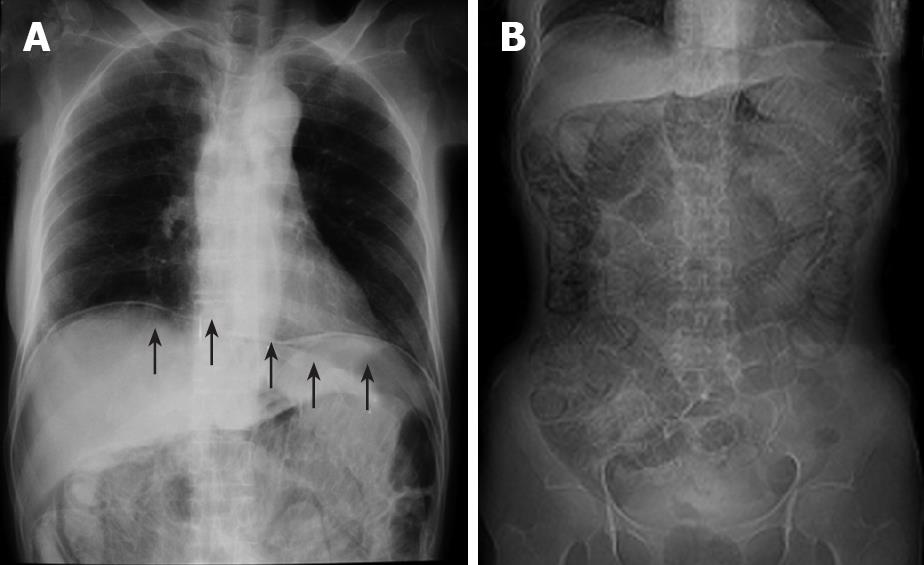

Figure 1 Abdominal roentgenogram.

A: Massive intraperitoneal free air (arrows); B: dilatation of the intestine and circular collection of intestinal gas.

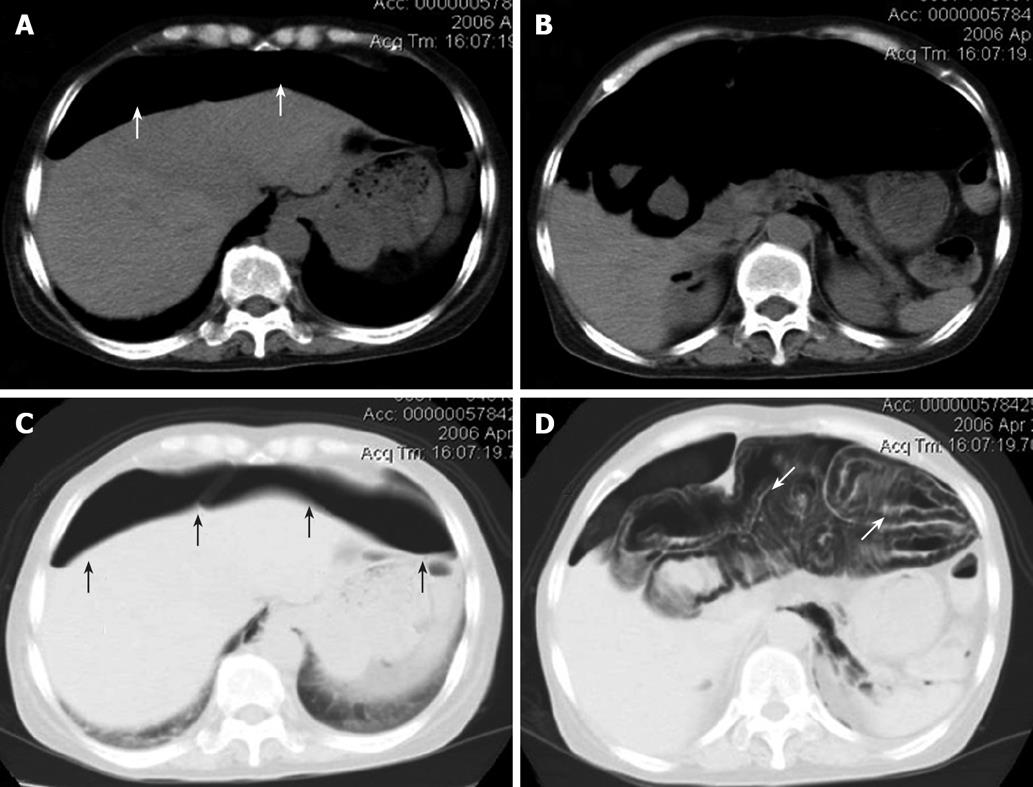

Figure 2 Abdominal CT scan images.

Massive intraperitoneal free air extending throughout the abdominal cavity (white arrows, A and B), and a stranded appearance of air collection within the bowel wall detected in the lung window setting, which extended from the jejunum to the splenic flexure of the colon. This indicated that the air was present within the bowel wall (white arrows, C and D). Black arrows indicate massive intraperitoneal air (C).

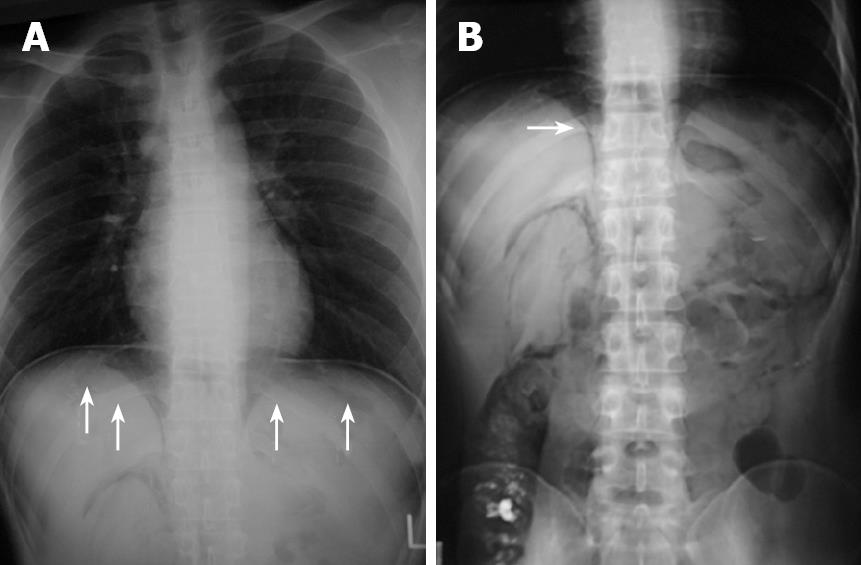

Figure 3 Roentgenogram of chest and abdomen.

It revealed massive intra-abdominal free air (arrows, A) and pneunoretroperitoneum (arrow, B).

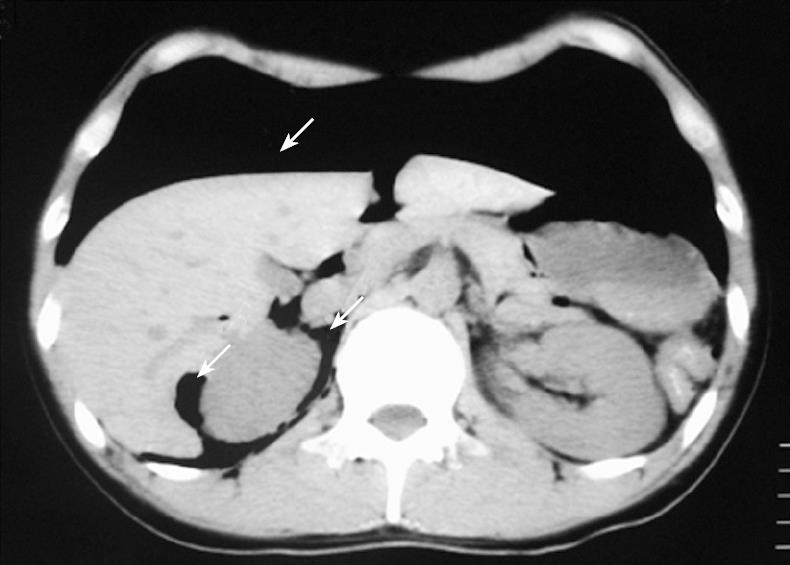

Figure 4 Abdominal CT scan, revealing massive peritoneal free air (arrows) that extended throughout the entire abdomen.

Pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis (PCI) is a rare disease characterized by the presence of multiple gas-filled cysts in the subserosal or submucosal wall of the large and/or small intestine. Patients either stay asymptomatic or present with gastrointestinal symptoms, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and abdominal pain. While the exact pathogenesis of PCI is not well understood, two theories, mechanical and bacterial, have been proposed based on the known clinical associations[1]. PCI is commonly associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, intestinal obstruction[2], ischemic bowel disease[3], necrotizing enterocolitis in premature infants[4], immunodeficiency such as AIDS[5], bacterial and/or viral infection[6,7] and drug therapy[8-13]. PCI may usually be found in a subserosal or submucosal location, and bowel distention and/or intraperitoneal free air can appear when the PCI is sufficiently extensive. However, PCI showing massive intraperitoneal free air and/or retroperitoneal air is extremely uncommon and only a limited number of cases have been documented[5,14]. We present two cases of PCI that mimicked perforated peritonitis, which required emergency surgery. Previously reported cases with PCI are reviewed and the significance of preoperative imaging is discussed.

CASE REPORT

Case 1 was a 58-year-old Japanese woman, who received corticosteroid therapy for rheumatoid arthritis in the department of internal medicine at our hospital. She complained of abdominal pain and distention and was referred to our department. The abdominal roentgenogram showed massive intraperitoneal free air (Figure 1A), dilatation of the intestine and circular collection of intestinal gas (Figure 1B). The abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed ascites and air collection within the bowel wall, which extended from the jejunum to the splenic flexure of the colon, which indicated that the air was present within the bowel wall (Figure 2). The laboratory data just before the operation indicated that white blood cell count was 14 900/mm3 and the serum C-reactive protein (CRP) level was 4.0 mg/dL. Although PCI was strongly suspected, the patient received corticosteroid therapy for the last 10 years, which may have masked the severe abdominal symptoms. The possibility of perforated peritonitis associated with unexplained ascites could not be eliminated, therefore emergency laparotomy was performed. At surgery, a large amount of free air exhausted when the abdomen was opened. Multiple gas-filled subserosal vesicles scattered throughout the surface of bowel wall and the mesentery were found, which were almost distributed entirely in the small intestine and the colon (data not shown). While there was a small amount of serous ascitic fluid in the abdominal cavity, the fluid was clear. Despite meticulous exploration of the abdomen, no evidence suggestive of hollow viscus perforation was found. The abdomen was irrigated with 1000 mL of saline solution. Culture of the ascitic fluid obtained at surgery was negative for any microorganism. Postoperatively, the patient received oxygen therapy for 4 d and the signs of PCI completely disappeared 5 d after surgery. The patient was discharged from the hospital 19 d after surgery. No recurrence of PCI has been found to date.

Case 2 was a 25-year-old man who had been receiving treatment for the colonic type of Crohn’s disease for the last 12 years. While he had received repeated doses of infliximab 31 times from 2001 to 2005, administration was discontinued because of the appearance of colonic stenosis. He was then followed up by treatment with azathioprine and 5-aminosalicylic acid. After the patient underwent total colonofiberoscopy and barium enema, abdominal distention continued for 2 wk. The patient then complained of abdominal pain and was referred to our department in June 2006. The abdominal plain roentgenogram revealed massive intra-abdominal free air and retroperitoneal air (Figure 3). The abdominal CT scan revealed massive peritoneal free air throughout the abdomen and a small amount of ascites (Figure 4). The laboratory data just before the operation indicated that white blood cell count was 4600/mm3 and serum CRP level was 1.8 mg/dL. To eliminate the possibility of perforated peritonitis and to confirm the diagnosis of PCI, diagnostic laparoscopy was performed. The laparoscopic findings revealed multiple glistering, translucent, gas-filled subserosal vesicles scattered throughout the surface of the bowel wall, the mesentery and omentum, which was compatible with PCI (data not shown). Although a small amount of ascitic fluid was present in the abdominal cavity, there was no finding suggestive of perforated peritonitis. Culture of the ascitic fluid obtained at surgery was negative for any microorganism. The postoperative course was uneventful and the elemental diet was started 8 d after surgery to facilitate the recovery. The patient was discharged from the hospital 19 d after diagnostic laparoscopy. The patient has remained healthy and no recurrence of PCI has been found to date.

DISCUSSION

PCI affects men more commonly than women, with a peak incidence at 30-50 years of age[15]. The sigmoid colon and its proximal side of the gastrointestinal tract has been shown to be the area that is predisposed to PCI, which is similar to diverticular disease[16]. The majority of patients are asymptomatic, therefore, the incidence of PCI may be underestimated. As a result of the high incidence of associated conditions, mortality rate of PCI in a collected series has been reported to be as high as 33%[17]. Furthermore, mortality rate of patients of PCI observed without surgery has been reported to be 18%, which suggests that emergency laparotomy is occasionally required.

The striking finding of preoperative imaging analysis in the present cases was the presence of massive intraperitoneal free air and/or retroperitoneal air that mimicked perforated diffuse peritonitis. Despite the fact that rupture of subserosal cysts of PCI results in pneumoperitoneum without peritonitis, accumulation of a large amount of intraperitoneal free air throughout the abdomen is extremely uncommon and only a limited number of cases have been documented previously[14,18,19]. Particularly, the presence of free retroperitoneal air as well as intraperitoneal air was detected in the plain abdominal roentgenogram and abdominal CT scan in case 2, which could also be signs strongly suggestive of gastrointestinal perforation. Although it is extremely rare, the presence of free retroperitoneal air caused by PCI has been reported previously[5,14]. Plain abdominal roentgenography is the most useful and easy way to ensure the diagnosis of PCI. Circular collection of gas in the bowel and mesentery is characteristic of PCI, and a review of 919 cases of PCI has shown positive abdominal roentgenography in two-thirds of patients[20]. Furthermore, recent reports have shown that abdominal CT and ultrasonography are useful methods for the diagnosis of PCI[19,21,22]. A stranded appearance within the air collection of the bowel wall in the CT images is characteristic of PCI, which indicates that the air is present within the bowel wall[1]. In particular, lung window settings have been reported to be important in the detection of intramural air, and obviate the need for intraluminal contrast to outline the circumferential pattern of PCI[22]. This technical observation could have potential clinical significance in the evaluation of patients with suspected intestinal ischemia or gangrene, in whom the appearance of intramural air is an ominous prognostic sign. Although these CT images were useful for the diagnosis of PCI in the present cases, the possibility of gastrointestinal perforation could not be completely eliminated because of the massive intraperitoneal free air and ascites.

In the present cases, because no gastrointestinal perforation occurred, no particular surgical intervention was performed on the bowel associated with PCI. Oxygen therapy was performed in case 1 and the signs of PCI substantially disappeared 5 d after surgery. Although oxygen was first used by Forgacs et al[23] in 1973 for the treatment of PCI, the minimal concentration and the optimal duration of oxygen have not been established. It was initially suggested that arterial oxygen concentrations in excess of 300 mmHg were required, which could be accomplished by delivering 70%-75% humidified oxygen at 8 L/min via a mask. Wyatt[24] has suggested that aggressive oxygen therapy should be continued for at least 48 h after complete radiological disappearance of all cysts, and that recurrent cysts are to the result of inadequate initial treatment rather than actual recurrence. No recurrence of PCI was detected during 2 years follow-up in the present cases.

Laparoscopic examination was performed on case 2 to precisely determine the cause of massive intraperitoneal free air, retroperitoneal air and non-infectious ascites. Although there was no gastrointestinal perforation in either of our cases, the cause of the ascites remains uncertain. Unexplained ascites associated with PCI has been reported previously[25]. The ascites disappeared as the PCI improved postoperatively in our cases, which suggests a possible link between PCI and ascites.

In summary, these cases highlight the clinical importance of PCI associated with massive intraperitoneal free air and/or retroperitoneal air that mimic perforated peritonitis, which required emergency surgery. Preoperative imaging modalities are useful to make precise diagnosis and further diagnostic laparoscopic examination is a useful adjunct to ensure the diagnosis of PCI.